Celine’s Winter 2023 presentation fulfilled the indie expectations it set—but the “sleaze” attributed to it was nowhere to be found

Celine’s Winter 2023 presentation may have been called The Age of Indieness, but it wasn’t the “indie sleaze revival” the fashion industry dubbed it as. It’s not even safe to say that subculture came back in full force this year, as many predicted it would. Sure, indie is in right now. But when wasn’t it? Ever since MTV featured Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” video, indie has treaded along mainstream’s peripheral vision. But just because something is indie, doesn’t mean it’s indie sleaze.

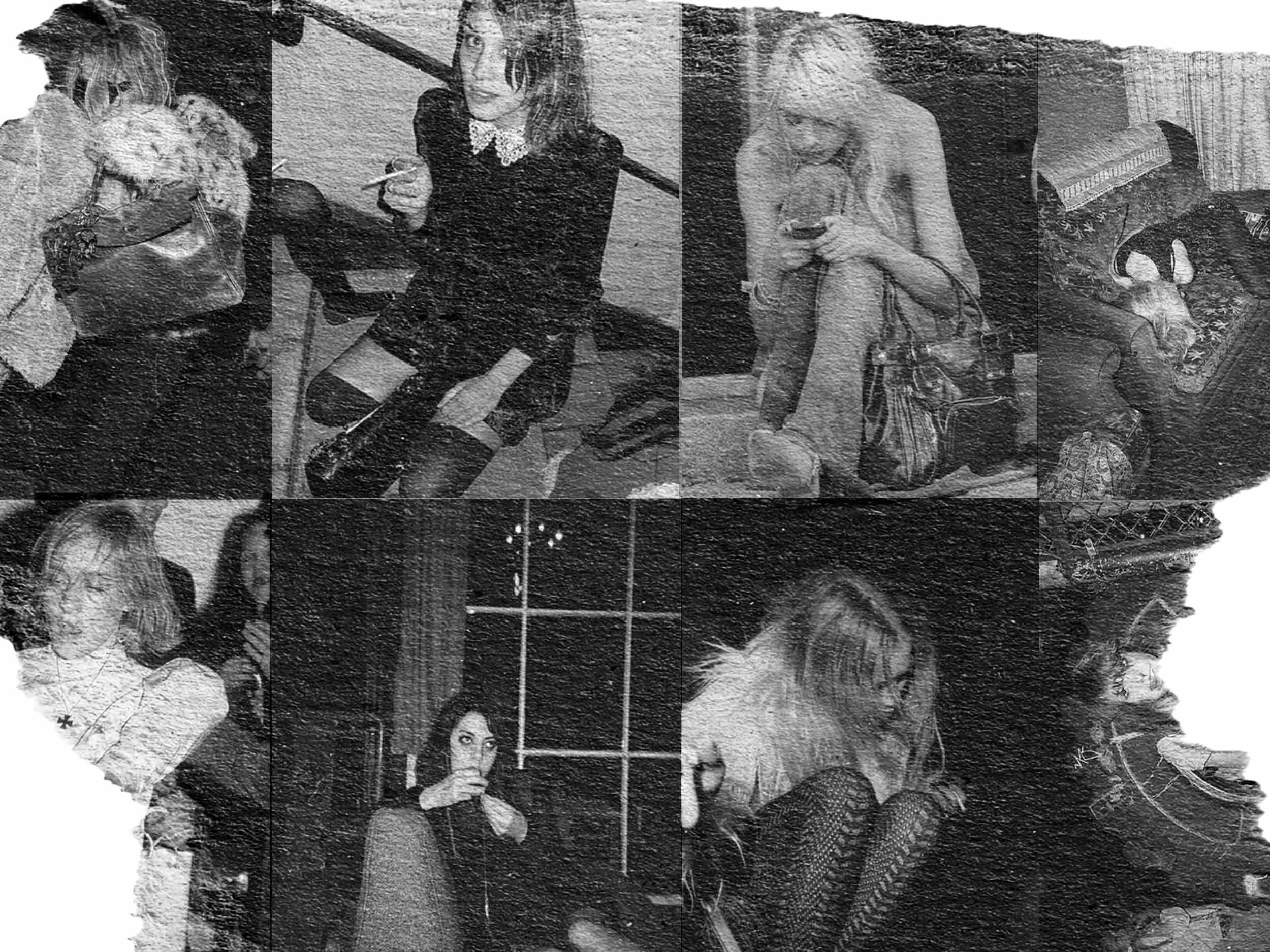

Indie sleaze references the mid- to late-aughts, and the early-2010s—an era when debauchery was praised, and the more disheveled you looked, the better. It was a cultural moment documented by The Cobrasnake during the rise of bloghaus, MDMA, and Vice. Participating hipsters were born alongside the internet, before its broadscale commodification and the normalization of polished social media profiles. People were allowed to live messy, unfiltered lives. After all, according to the dictionary, sleazy does mean “low character, dirty, cheap, or not socially acceptable, especially relating to moral or sexual matters.”

Nothing from Hedi Slimane’s latest collection is any of those things. His show consisted of impeccable tailoring, tasteful styling, and pristine casting. Disco shorts, neon-colored stockings, unnecessary sweatbands, and oversized square-framed glasses are nowhere to be found. Instead, everyone looks polished in their somewhat-alternative attire. Where are the people who look like they got dressed in the dark? Indie sleaze used to be tacky, messy, and raunchy. Now, it’s embodied as a near-homeopathic dilution of the original ethos: carefully-smudged eyeliner, rather than the mess produced by sleeping in your makeup.

The collective misconception of the term “indie sleaze” is, in part, a side effect of the social instinct to label everything. To make sense of the world around us, we constantly come up with classifiers that differentiate one thing from another. Today, an abundance of microtrends are created almost daily on the internet, but most reference something that already exists: “Gorpcore” is repackaged “granola”; “balletcore” is repackaged “coquette.” There is a collective thirst for definition, as evidenced by the popularity of terms like “indie sleaze”—but in simply renaming the aesthetic without truly embodying it, we’ve lost track of the original sleaziness of it all.