For Document’s Winter/Resort 2023 issue, the photographer uncovers the nuance of the working-class life along Arkansas’s White River

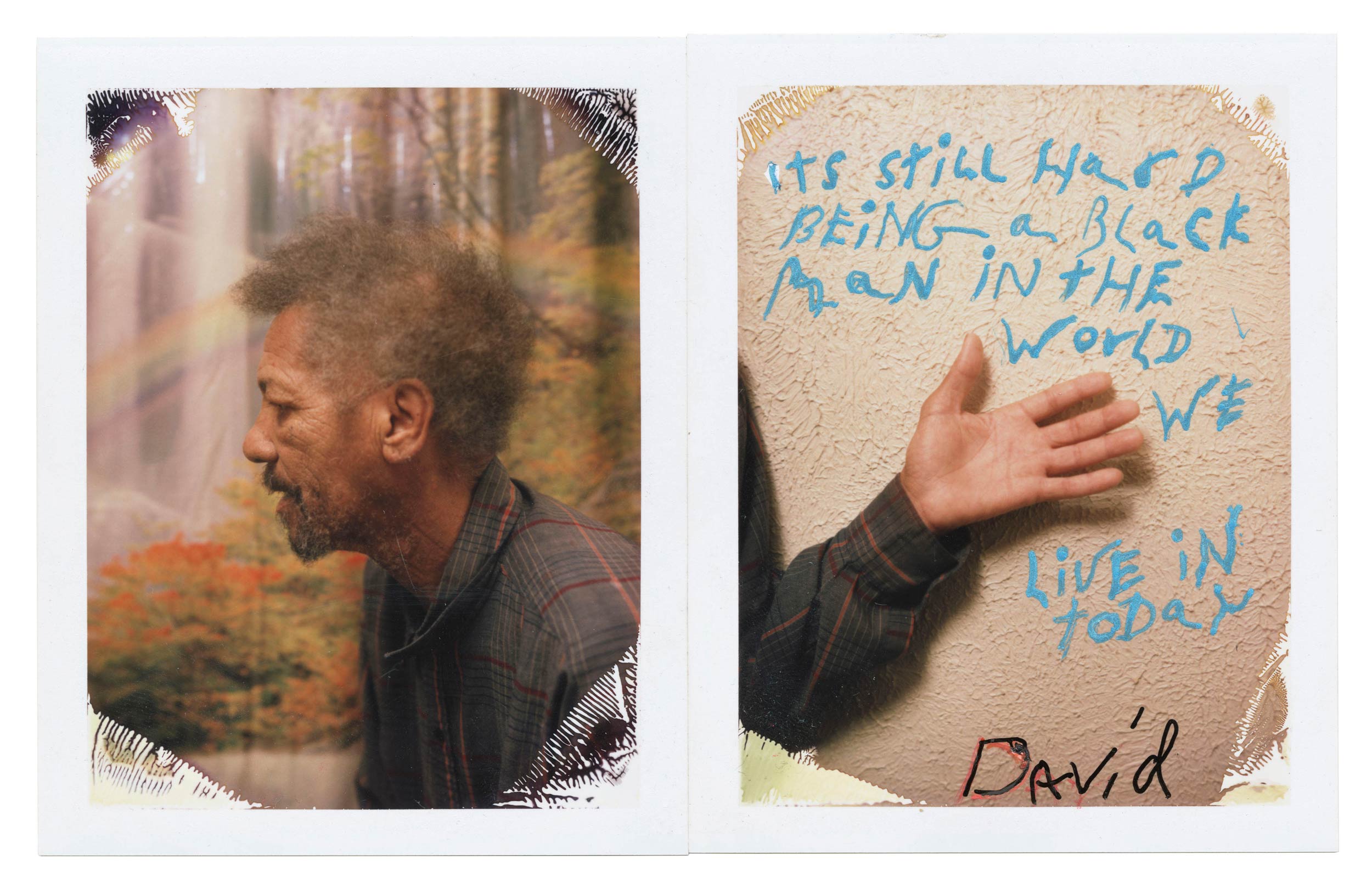

“I look worn down,” a woman writes, her script wrapping upwards, framing her portrait. Her hair is pinned back, her expression resolved, while her arms fall flat at her sides. “My dream is to get married and be a model in pictures.” Her tone leaps seamlessly from diffidence to desire.

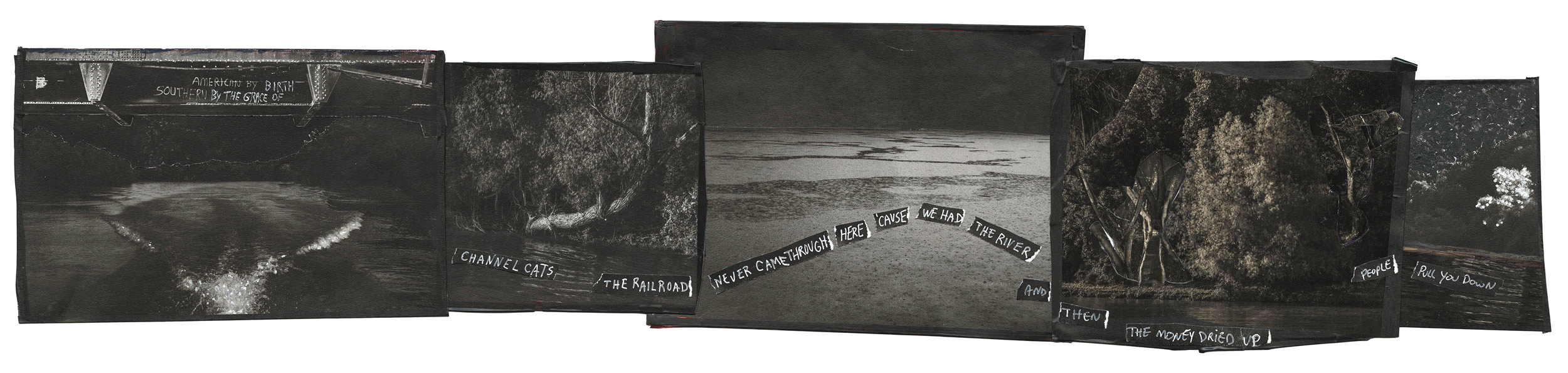

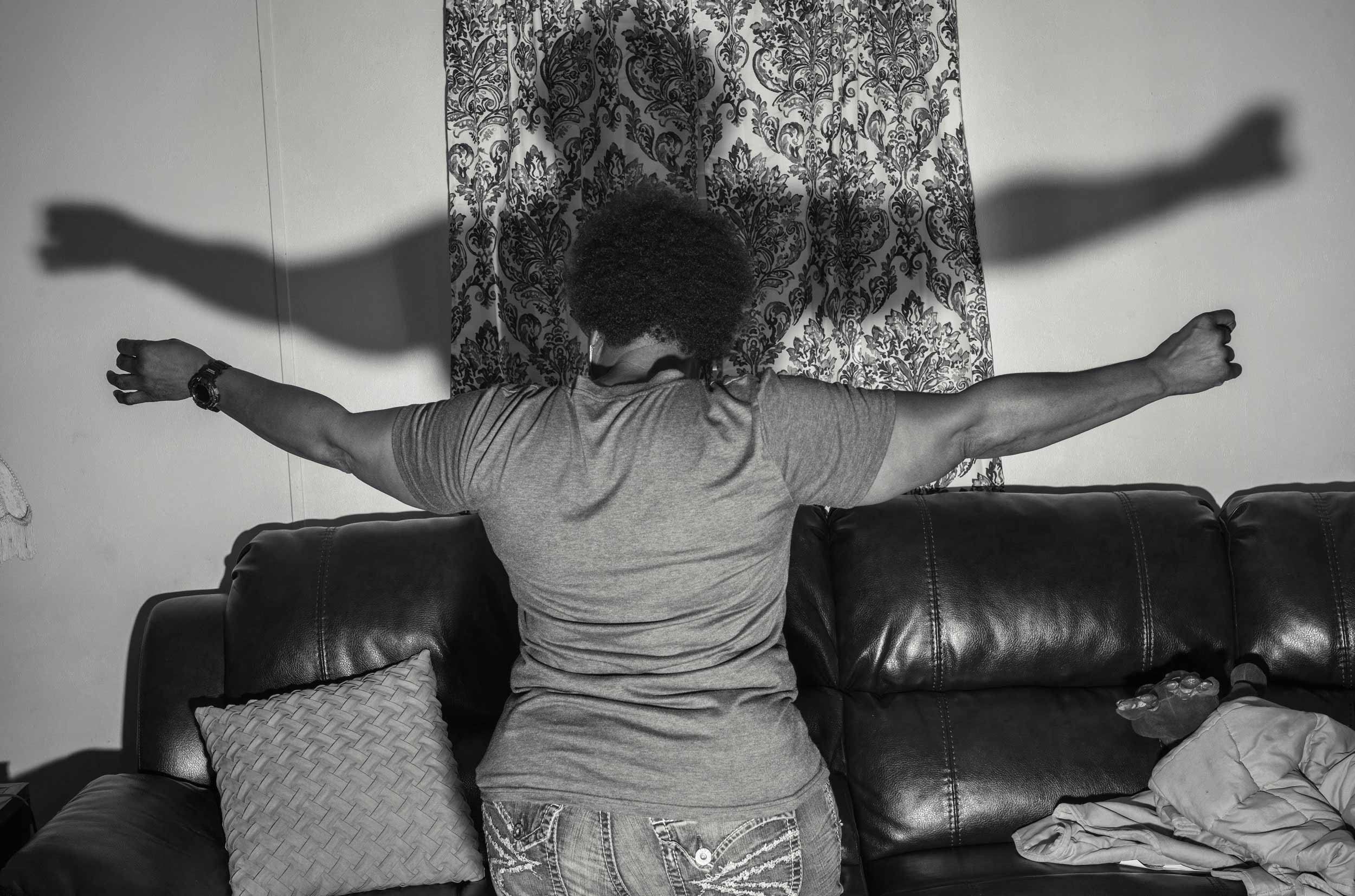

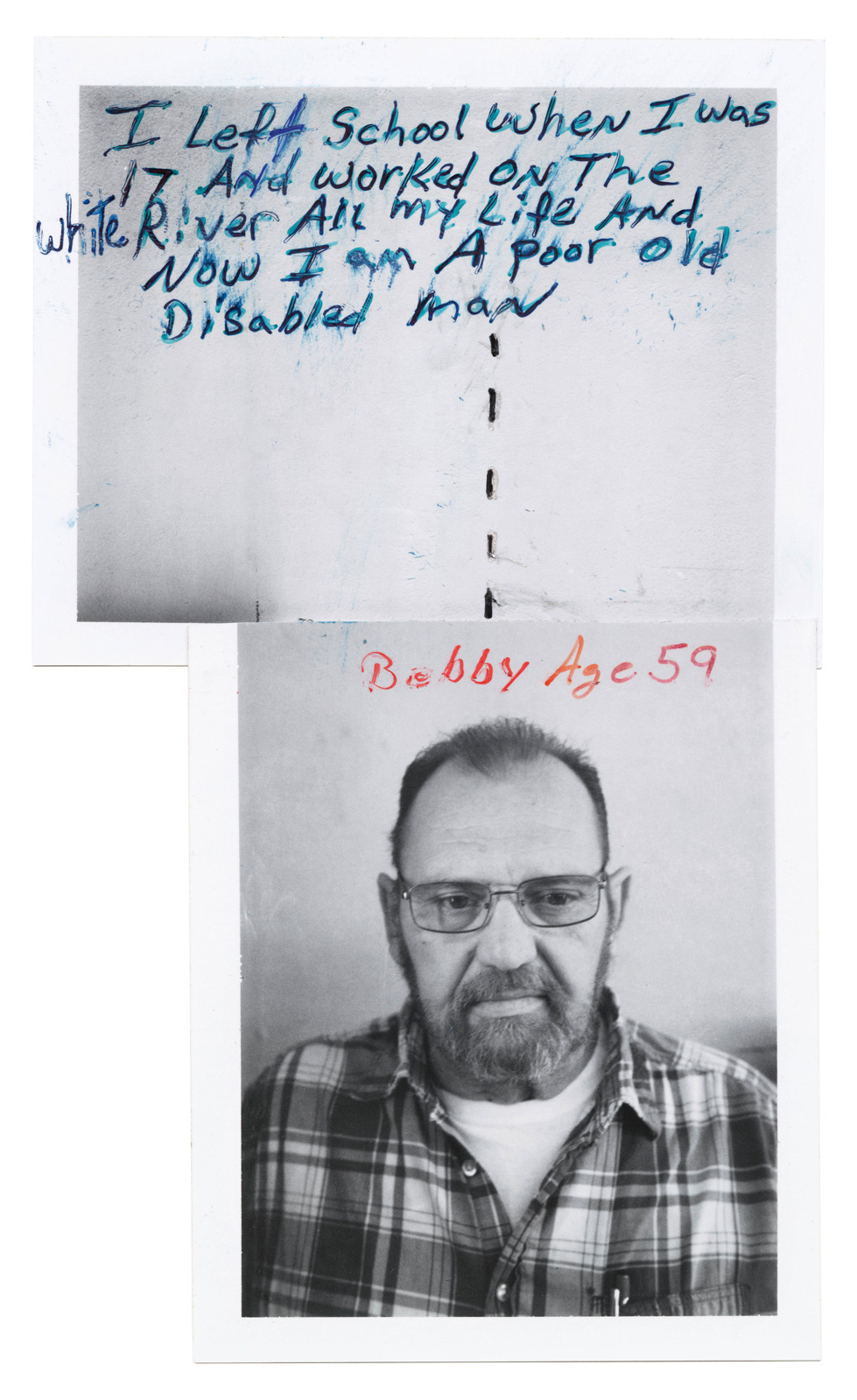

Turquoise text rounds the corner of another image—a daughter confessing, “My mom’s days are fading with dementia… Sometimes I SCREAM from it all.” Jim Goldberg’s cinéma vérité-style works invite co-authorship from their subjects, centering the complexity of individual character above all else—whether directly, through the application of writing around a print, or subtly, in the perspectives that emerge in the uncontrived expressions of Goldberg’s sitters. Even with place-based images, humanity is foregrounded by the lingering influence of former and current inhabitants: a family in their yard on a Sunday evening, the pelt of a bear sprawled lifelessly against the wall of a hunting lodge, a controlled burn consuming a dying tree.

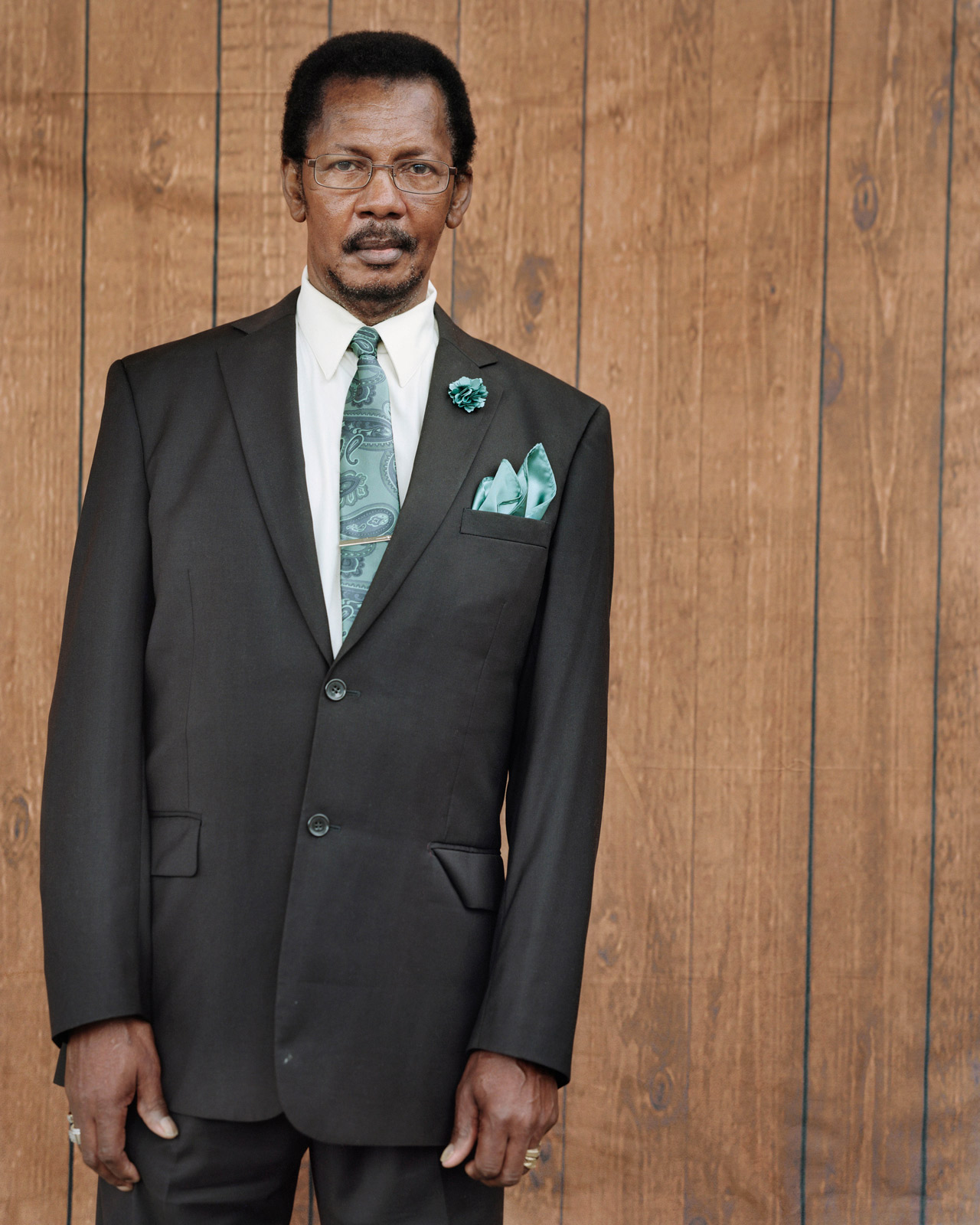

Since the late-’70s, Goldberg has challenged the conventions of documentary practice, combining text, ephemera, and found images with his photographs to tell deeply personal stories. In early 2020, he traveled to the working-class towns along Arkansas’s White River, investigating how histories of lineage and land ownership continue to shape the dialogues and perspectives of the Delta’s residents. There, he was acquainted with the intimacies of small-town life—landscapes, architectures, and familial ties. “Every small town has its share of mysteries and secrets, of racial divides, of haves and have-nots—[its traditions around] how people dress and present themselves, [its memories] of which buildings fall apart, and which are propped up.”

Storytelling is inherently fragmented, and always capable of expansion. Goldberg’s first trip was cut short by the COVID pandemic, and in the intervening year, he maintained the relationships he’d built with residents from a distance, eventually returning with greater cultural familiarity. The photographer was continually drawn to the White River and its many whirlpools, created by opposing currents—a metaphor for the tensions within its surrounding communities, and the country at large. Says Goldberg, “These people’s lives are a true reflection of contemporary consciousness.”