In two concurrent visual arts exhibitions, the Academy Award-winning auteur explores the themes he's know for in the mediums he isn't

Though best-known as an Academy Award-winning auteur, painting is David Lynch’s first love. Two concurrent New York exhibitions—Big Bongo Nights at Pace Gallery and I Like to See My Sheep at Sperone Westwater—offer a window into the lesser-known practices that build into the artist’s unsettling universe.

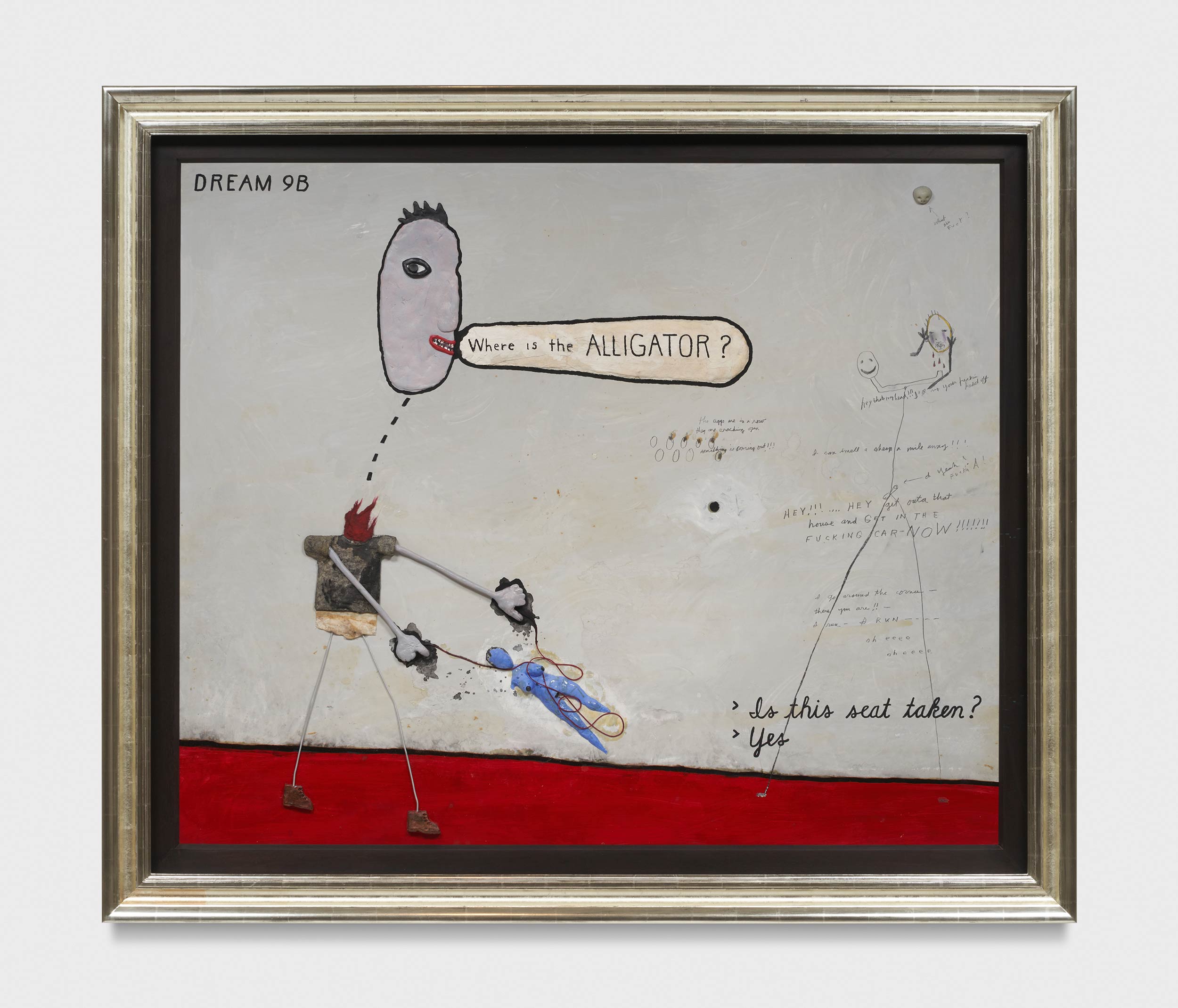

In Big Bongo Nights, Lynch’s sculptural metal and wood lamps cast an amber glow across a series of multimedia paintings with distorted characters (Bobby, Billy, and Martha) and symbols (an airplane, a gun, and a woman’s head), framed by text scrawled across the canvas. The layers of references are like rebus puzzles that nudge the viewer to examine his work up close.

“It’s like an aerial view,” one visitor remarked to their friend at the show’s opening, as they peered at Lynch’s work aptly titled Head on Hill with Cloud and Airplane (2021).

“Doesn’t it look like a plane window?”

“It looks really eerie. Are bombs being dropped? That looks like a mushroom of smoke if you step away.”

“I love the severed head.”

Bill Griffin, the Managing Partner at Pace, was speechless the first time he visited Lynch’s studio over a decade ago. “It was unlike anything in the contemporary dialogue—so uniquely his, and yet so tethered to the human condition in this very subconscious way. I found it to be powerful and haunting and elusive,” he says.

“David provides you with the pieces, but he wants you as the viewer to complete the picture,” says Pejman Shojaei, the Associate Director at Pace. In I Call Out Your Name (2022)—a mixed media painting created just a week before the exhibition at Pace—a visceral private conversation plays out on the canvas in the form of a letter: A red airplane looms above an off-kilter drawing of a man with outstretched arms and a comic book-style speech bubble that proclaims, “I call out your name!” A woman’s head protrudes from a gash in the figure’s side, a rudimentary sketch of a gun hovering below him amid various bits of cryptic writing. A letter scrawled sideways lower on the canvas begins, “Dear Martha, How are you? Here the weather is horrible—raining all the time—cold—cloudy, miserable—so depressing.”

When asked if Lynch ever stopped painting, Griffin answers with an emphatic no. “He’s never left it,” he says. “He’s always been there. It’s not always exhibited out into the world—he’s not making it for the market, he’s making it for himself.” A siren whirred in the background. “How Lynchian,” Griffin remarked.

The term Lynchian became a oft-used term to refer to films that echo Lynch’s signature surrealist take on the everyday life, but that same style was first born in his paintings. As the artist’s self-perpetuated lore would have it, his idea of a “moving painting” can be traced back to 1967, at his art studio at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. While standing in front of one of his virtually all-black paintings of a garden, he felt as if a wind was coming through the canvas, swaying its plants.

A year later, Lynch created his first moving painting, “Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times),” a minute-long animated film that was constructed to be played on loop six times. It begins with the sound of a siren and a countdown from four. Plaster casts and drawings of Lynch’s head appear layered on screen, their stomachs fill with red paint. When they can’t hold anymore, splatters of white vomit cascade down the frame. Soon after its creation, Lynch moved to Los Angeles and began working on Eraserhead (1977), a letter to his time in Philly.

To this day, he creates everything from his weather reports to his lamps and paintings in home studios designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in the ’60s in the Hollywood Hills just off of Mulholland Drive. “Sometimes I see things, shapes or something that would go inside of it and that leads to furniture or film,” the artist said, in reference to his home.

Narrow roads twist up the hills lined with wild foliage, leading to his pale pink, concrete residence and two neighboring houses-turned-studios. One of the buildings was first used as the main location Lynch’s his surrealist thriller Lost Highway (1997). Outside of making fine art, the artist films daily weather reports from his studio.

His weather reports are mostly meditative and predictable: Lynch always announces a sunny day with the phrase “blue skies and golden sunshine all along the way.” On rare occasions, he breaks form to dispatch his view from the mundane to the political: an impassioned thank you to his viewers, a pointed 4-minute long video criticizing Putin’s decision to attack Ukraine, a birthday announcement for Sir Paul McCarteny, and a Black Lives Matter sign positioned behind his chair.

Other times, outside context from the world and Lynch’s life frame the simple videos. On the day of his opening at Pace, Lynch began his report with a disorientingly shaky camera: “It’s November 4, 2022, and if you can believe it, it’s a Friday once again!” he exclaims as the camera settles to focus on his shock of white hair and dark wayfarer sunglasses. The weather in Los Angeles for the day? “A few clouds, but mostly blue skies and golden sunshine all along the way.” The soundtrack? “I Love How You Love Me,” a soulful ’60s ballad by The Paris Sisters. A commenter enthusiastically notes that Lynch used the song in a scene from Twin Peaks: The Return. The video has been viewed approximately 12,000 times with over 300 comments.

From his weather reports to his lamps to his paintings, everything Lynch creates is connected by the location in which they are made—his home. “Sometimes I see things, shapes or something that would go inside of it and that leads to furniture or film,” he said.

Lynch spends time with each work after he creates it, and it is easy to imagine him doing so, his home aglow with the golden light of his lamps. “His life and his art are inseparable,” Griffin says. ”When he sleeps, when he taps into the unconscious, when he meditates, all of this is one for him.”