For Document, the artists meet to discuss object theory, museum hierarchies, and the responsibilities of creatives who grapple with American stories

Objects have life force—a fact Caitlin MacBride knows well. The artist’s practice revolves around the power that’s contained in historical artifacts, from tool sets to Shaker bonnets to beds and chairs and desks. She combs through museums’ archives, noting which sorts of things are deemed worthy of institutional ownership—and then, which are destined to make it on display.

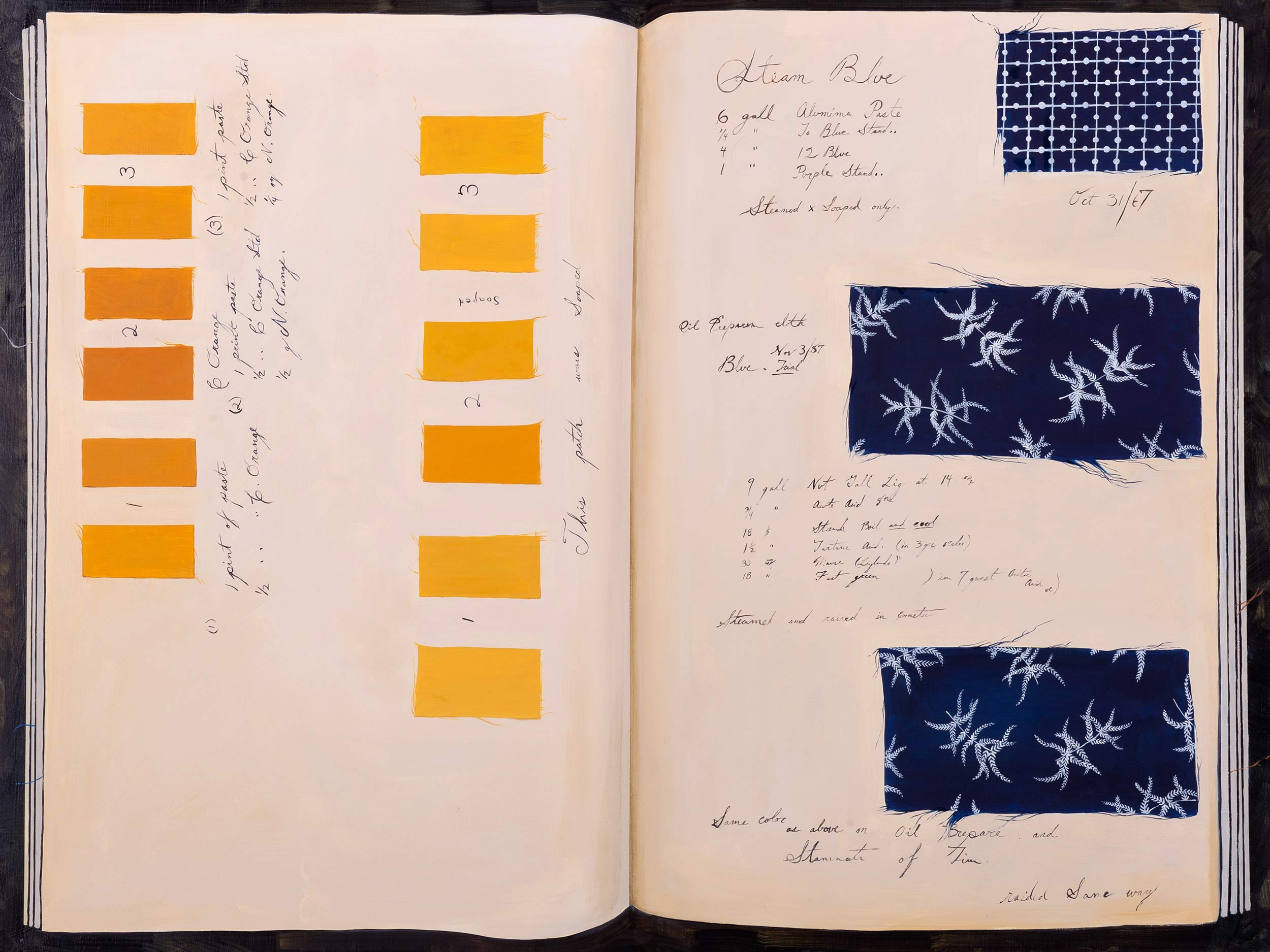

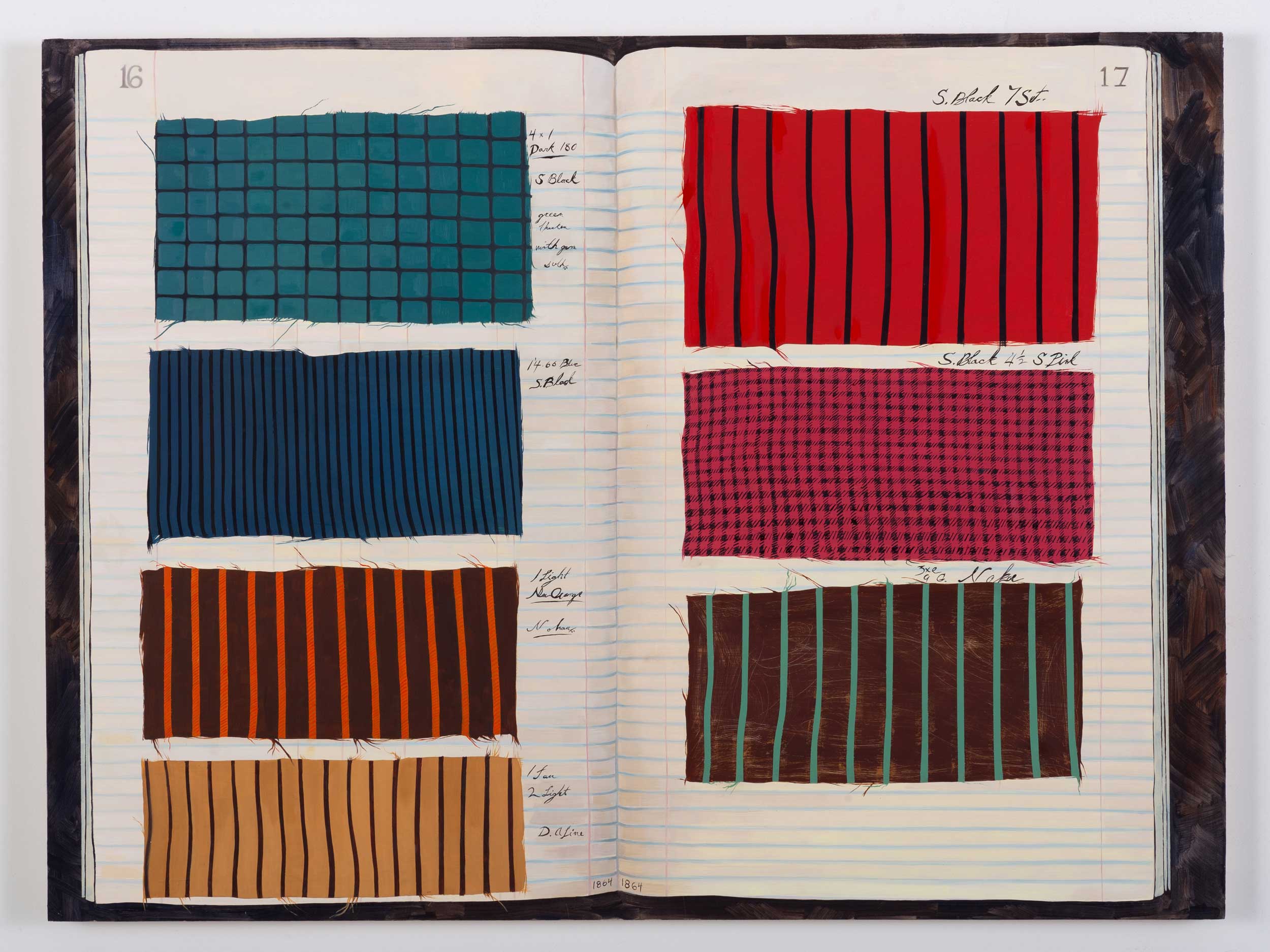

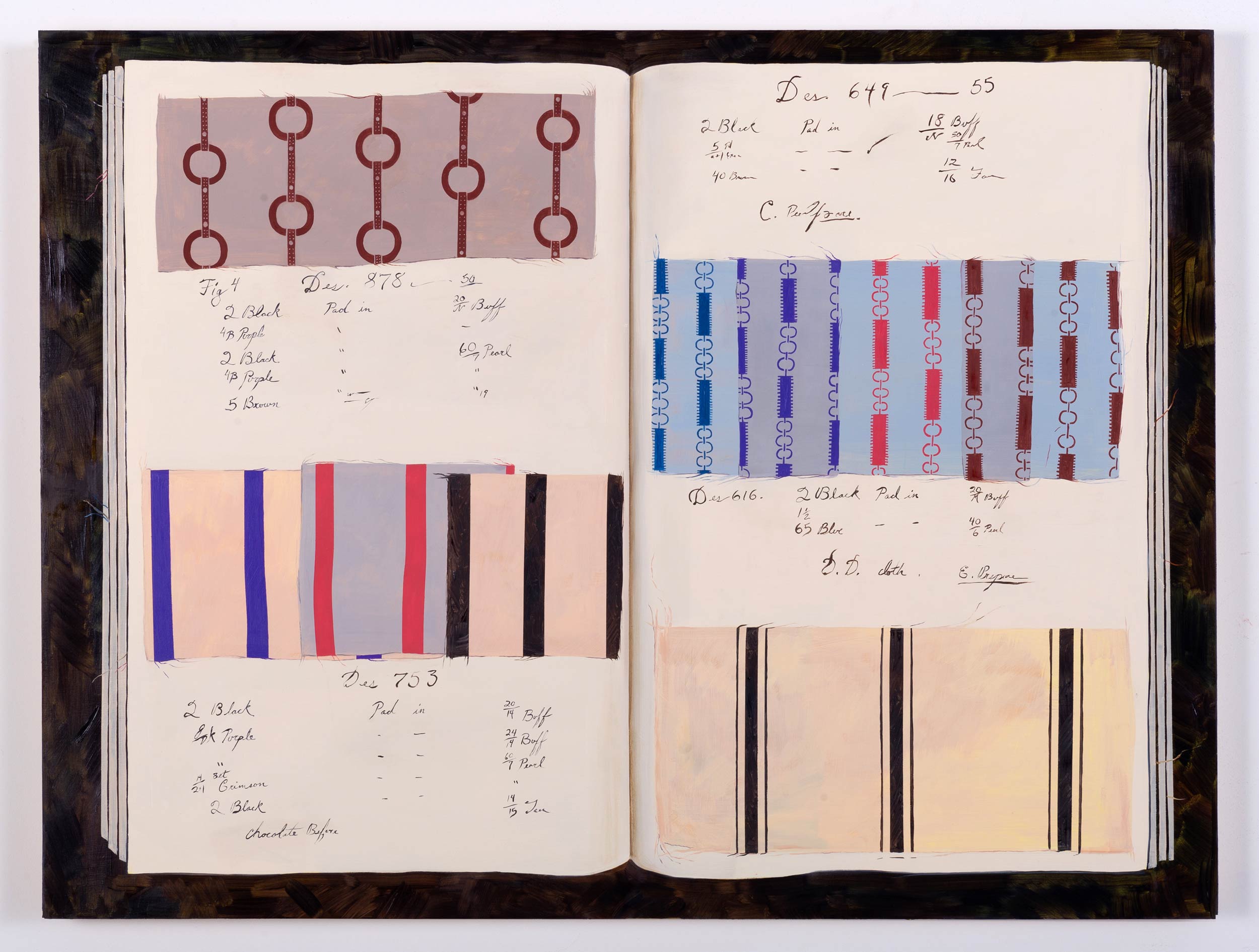

MacBride’s latest exhibition, Dyeing Notes, just closed at New York’s Deanna Evans Projects: a series of oil paintings that render 19th-century fabric sample books, part of the permanent collection of the Cooper Hewitt Museum. “They’re from textile mills in Massachusetts,” explains the artist. “Really beautiful artifacts, made by the managers of the mills, who would keep notes on how much of each color went into the dyes to make a specific print.” MacBride herself is from the Northeast, thus personally curious about these sorts of American stories, and how we tell them: “It does get sad. I see objects that used to have some totally different meaning, [sitting] in a museum… It gains a different meaning—around an institution, an establishment, prestige.”

MacBride’s shares a studio complex with the artist Julia Weist, whose work likewise engages with the archive. The latter’s most recent project, Governing Body, challenges the film rating system of the Motion Picture Association—a descendent of New York’s Motion Picture Division, which operated between 1921 and ’65. In collaboration with Archive Films, Weist spliced together a short composed entirely of banned scenes—stereotypical depictions of non-male taboo—deemed unsuitable for public viewing then, and rated R today. “Artifacts are given institutionally-determined meanings that reflect and perpetuate the values of the museum,” she says in conversation with MacBride—a statement easily transferable to the film industry, and what it considers art of good merit. “It’s less common for artifacts to be contextualized with meaning that’s flexible and sensitive to community-authored perspectives.”

The artists’ practices—though historically-based—tease out similar takeaways, firmly rooted in the present. For MacBride, it’s the questionable virtue of our art historical hierarchy: how putting something in a museum removes it from its context, and how museumgoers are implicitly told what to value. For Weist, it’s how we invite institutions to make meaning for us, via viewership rubrics that often seem arbitrary, or at least removed from the true intent of a film at hand. For Document, MacBride and Weist discuss object theory, the parallels between their work, and the responsibilities of an artist grappling with American conversations.

Julia Weist: Your exhibition Dyeing Notes, which was just on view at Deanna Evans Projects, was one of the best painting shows I’ve seen this year. Can you set the stage for us? How do you describe this body of work?

Caitlin MacBride: [Dyeing Notes] has been in my head for a while. They’re oil paintings on wood panels, based on fabric sample books that are in the collection of the Cooper Hewitt Museum. The books were made in the mid-1800s, around the time of the Civil War. They’re from textile mills in Massachusetts—really beautiful artifacts, made by the managers of the mills, who would keep notes on how much of each color went into the dyes to make a specific print.

Julia: One of the places where our artistic practices overlap, I think, is that we’re both interested in what historical materials get saved, and by whom. And with what goals in mind: preservation, conservation, curation, display. What does it mean to you, that some historic objects are more accessible than others—that some are better resourced, and therefore more visible?

Caitlin: I got into working with museums, which is what I mostly do at this point—things in archives, or things that have been deaccessioned. I started with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was really wild to see what was put on display, and what wasn’t, but [still exists] in their collection. You can search anything on their online archive—put in a word like ‘cat’ or ‘dog,’ and 8,000 things come up. So they obviously can’t have it all [in the galleries]. But the Greeks and Romans have fragments of things on display. And that’s sort of rare for a lot of other cultures, like Pacific Islander or African art. It might be because they’re wood instead of marble, but oftentimes, I think it’s just our art historical hierarchy—what most of us were taught to consider valuable.

I really love local museums. One of my favorites is the Museum of Appalachia, down in Tennessee. All of the information cards are done with Sharpie by this one guy, but it’s a five-building museum—it’s huge. There’s something to the way that things get valued that I’m interested in. When it becomes part of a museum, it becomes art in some way—especially at a place like the Met.

Julia: I’m a big fan of Gala Porras-Kim’s work, and I believe you are, as well. As you know, she examines the pillaging and the extraction that’s inherent to a lot of the museum systems you were just discussing, and also the taxonomic indexing that collection objects receive. Through this indexing, artifacts are given institutionally-determined meanings that reflect and perpetuate the values of the museum. It’s less common for artifacts to be contextualized with meaning that’s flexible and sensitive to community-authored perspectives. Do you think that the acquisition by the Cooper Hewitt Museum of the fabric sample books that you worked with helps or hurts these objects’ ability to represent a complex history?

Caitlin: With these specific objects, it feels good for them to be in the Cooper Hewitt; they have such an incredible ability to conserve things. And primarily, it’s [good] because these fabric sample books are from a similar area—they’re from the Northeast. New York dealt with similar issues around textile mills and production and design. And the Cooper Hewitt is a design museum. It’s an interesting frame for these pieces. At one point, I started focusing on objects that I felt had a similar background to me. I’m [also] from the Northeast. It became an interesting way of studying my own history, or at least the history of my ancestors who came to Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island.

“The Shakers were incredibly against industrialization, which was so prevalent at the time when they were living. This felt like a really American conversation, between mass production and a more handmade or bespoke or personal relationship to the object you’re making.”

The objects that Gala Porras-Kim is working with… I love the thing she [expresses], about how returning or repatriating the object is not necessarily just giving it back to the people, but also potentially giving it back to, like, a water god. And what does that mean? That kind of outside-the-box thinking on these kinds of subjects is something that artists are really amazing at.

I think it does get sad; I see objects that used to have some totally different meaning, [sitting] in a museum. There’s only so much that wall tech can do. Something may have been a holy object in another culture, or something that someone used really casually, day-to-day. It gains a different meaning—around an institution, an establishment, prestige. With my work, I am interested in turning the object itself into a piece of art, because I think it’s almost continuing that cycle where the thing enters the museum and becomes associated with art [automatically].

Julia: Throughout your career, you’ve transformed visual research into visual artwork, as you were just describing. I wonder what the difference is for you in painting an artifact versus a landscape, or a still life versus a portrait?

Caitlin: It always starts with the photos that are taken by the museum—a more documentarian view [that’s there] before I step in. I’m interested in that scientific way of seeing, which is usually how museums do things. Sometimes it has a ruler next to it, or a color scale.

I’m also interested in object theory, and the power that objects can have. They can take on a life of their own. Transitional objects—how the things that young children latch onto, for a sense of security, are an extension of the mother, or how fetish objects have a kind of sexual power—can take on meaning that we would normally [bestow upon] humans.

Julia: You’ve focused, for many years, on objects from the Shaker tradition. In some ways, Dyeing Notes is a transition to a new body of work. Do you see it as a departure or an extension?

Caitlin: Not necessarily a departure, but kind of the other side of the conversation. A yin-and-yang thing. The Shakers were incredibly against industrialization, which was so prevalent at the time when they were living. This felt like a really American conversation, between mass production and a more handmade or bespoke or personal relationship to the object you’re making. It’s something we’re still grappling with right now—what kinds of objects you bring into your life. It becomes a class distinction in some ways, of who can afford things that are made by hand. A lot of people struggle ethically with consumption in that way.

At the same time, they both feel like really American stories—of industrialization leading to what we have now, as far as the resources at our fingertips, and also in the way that a very considered craft has always been part of the American tradition. In some ways, the Shakers were a utopian community. [These were] utopian ideals that most of us aspire to: to live in such a considerate way, to provide for ourselves or for our communities. And yet, without industrialization, it’s hard to see where our culture would be right now.

Julia: Earlier in this conversation, you said that the fabric samples in the paintings were made of cotton and created between 1862 and 1867—meaning that most were produced from raw materials, and harvested through chattel slavery and forced labor. Then they were processed in mills in the North. Can you expand on that?

Caitlin: The issue is really tied to being an American painter. Having grown up in the Northeast, I think a lot about the historical structures that are still standing—the literal buildings, but also the wealth that grew from industrialization. It’s all around me, from the old mill building that my studio is in, to the funding that built basically every school I’ve ever been to, to now [the act of] teaching. A few years ago, I spent a semester as an artist-in-residence at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. It was my first time living in the South. I got into thinking about the dynamics of the history there, and its connections to the cotton industry. In the North, we often think of the South as ‘responsible’ for slavery. But the technological advancements of the mills in the North, that was what was driving the massive amounts of cotton that were required. It made me think about us as a larger country—about the Northern role and responsibility. It’s one of the things that gets left out when we historicize things. But it’s there, in the objects. The fabric samples that I painted in the show are half-cotton and half-wool; they’re known as delaines. It was a time of transition in American production, where they were using wool because it took the dye well. But cotton was still growing and growing, industry-wise.

One of the things I learned was how large, how global of an issue it was. There’s this amazing book, Empire of Cotton by Sven Beckert. Cotton production was originally happening massively in India, partially in China. And because of global capitalism, it was really destroyed by the English Empire and the transition to America—which kind of became a new empire. [The industry] sort of transitioned back to those countries, which are still producing a lot of our cotton. It’s become a historical issue for us in the US, but it’s very actively happening [elsewhere] in the world, and still part of a lot of oppression.

Julia: With that in mind—working off what you said earlier, about looking to your own education for an individual perspective on the historical topics you’ve been talking about—have you ever used artifacts from your own past, or your immediate family’s past, in your work?

Caitlin: I haven’t. I thought of the Shakers as a stand-in for my own upbringing, which was fairly religious and working-class and, in some ways, utopian—a lot of very high ideals. I collect because the members of my family are very into collecting. I’ll tell them specific things that I’m looking for. Like, ‘I’m looking for wooden tools right now.’ And each time I see them at a holiday, I’ll get a couple more tools. I’m hoping to show them at some point, alongside the paintings. But in the meantime, I’m interested in steps of removal. For me, the museum and the way it documents things is a step of removal; and then there’s existing in a different time period. It’s interesting to look into who owned or used these objects. It opens things up so that I’m able to be in communication with people from other places, or totally different time periods.

Julia: Where does your work go from here?

Caitlin: I’m just meditating on the show that’s up right now. But I do want to continue working with the idea of mill systems and the exchange of goods between the North and South. I realized that a lot of the cotton canvas I paint on is still made down in Georgia. And because I have been collecting a lot of objects, which I think of as my muses—that kind of sit alongside my work, even if I’m not literally painting them—I want to try to make some works that incorporate them.