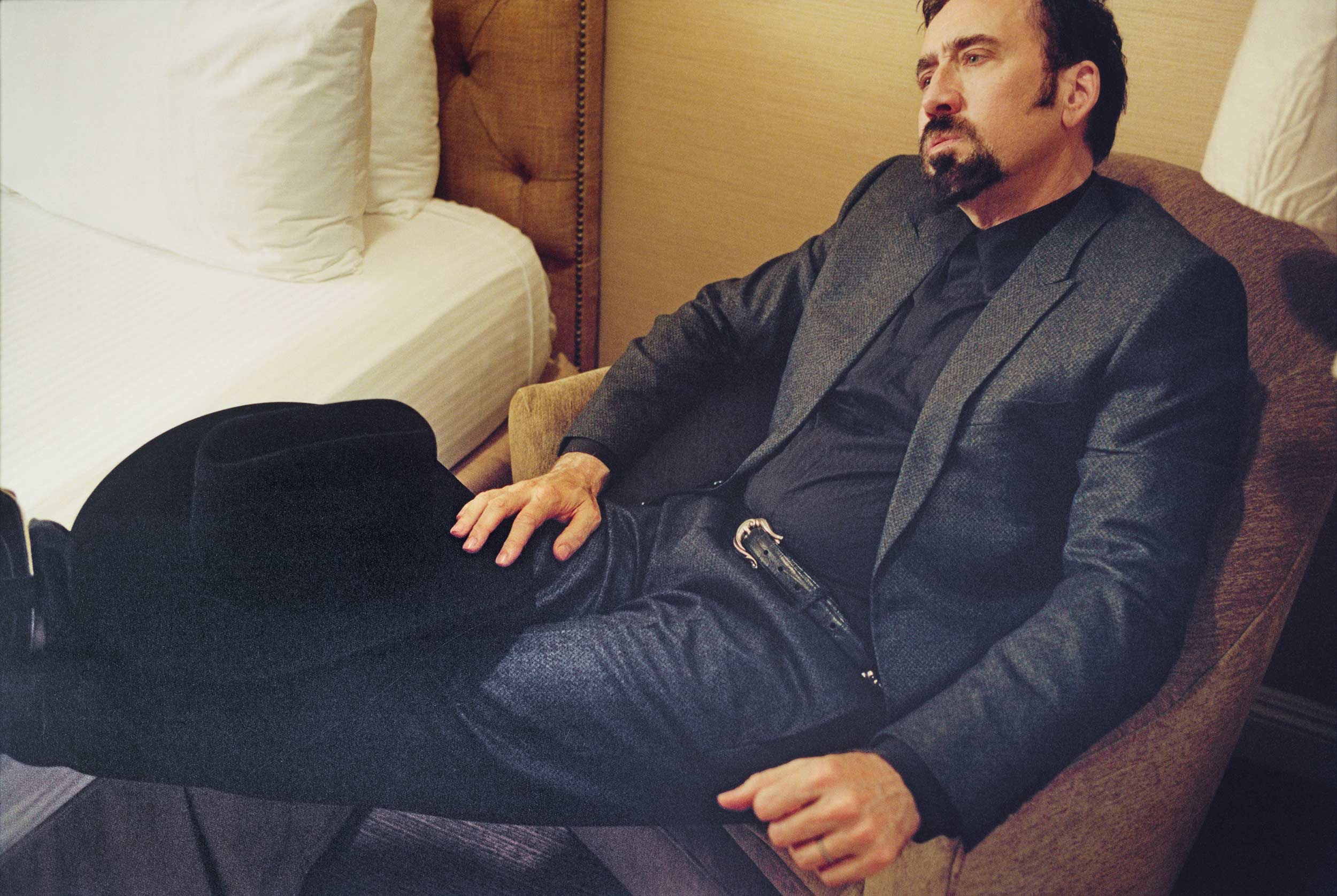

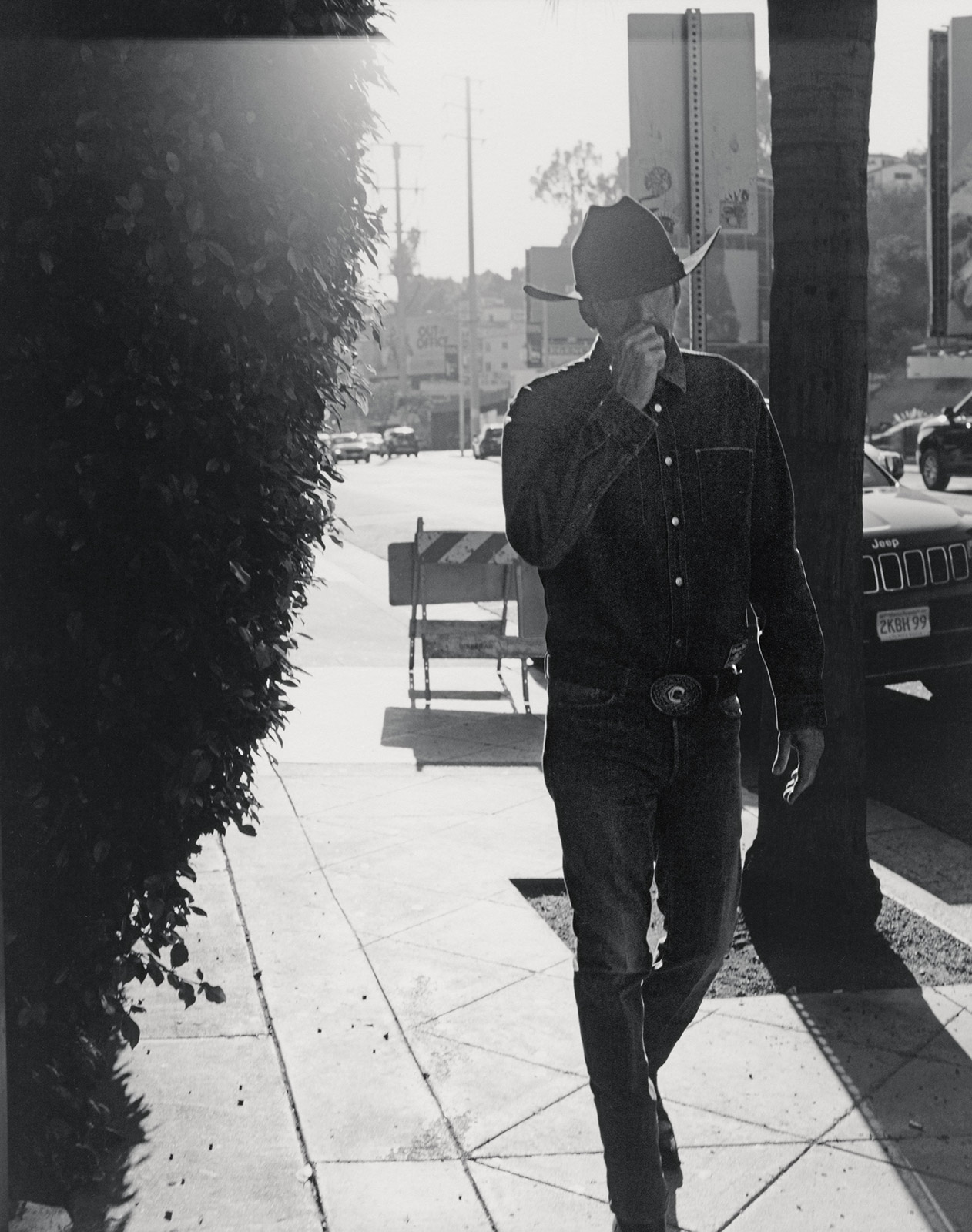

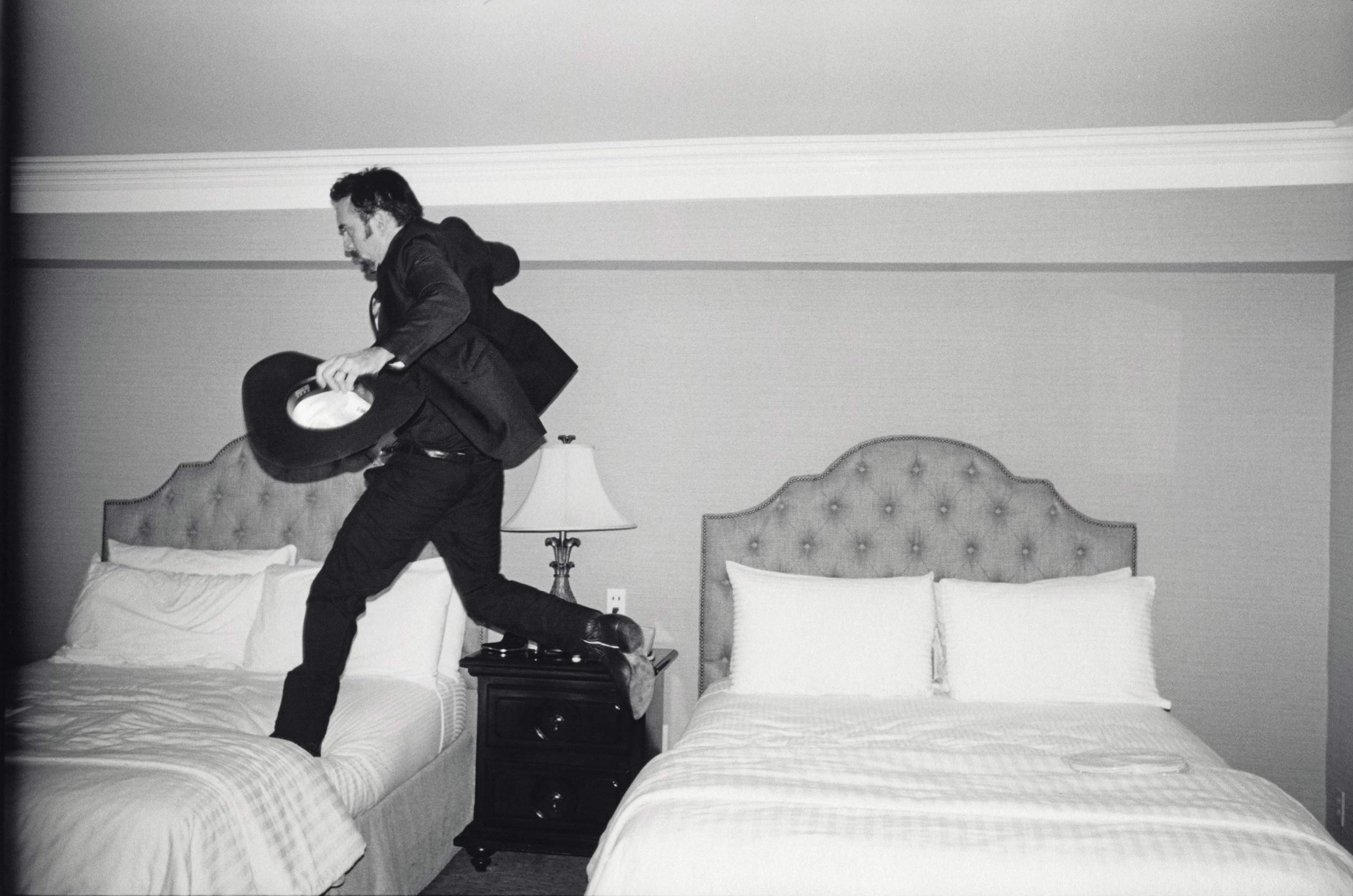

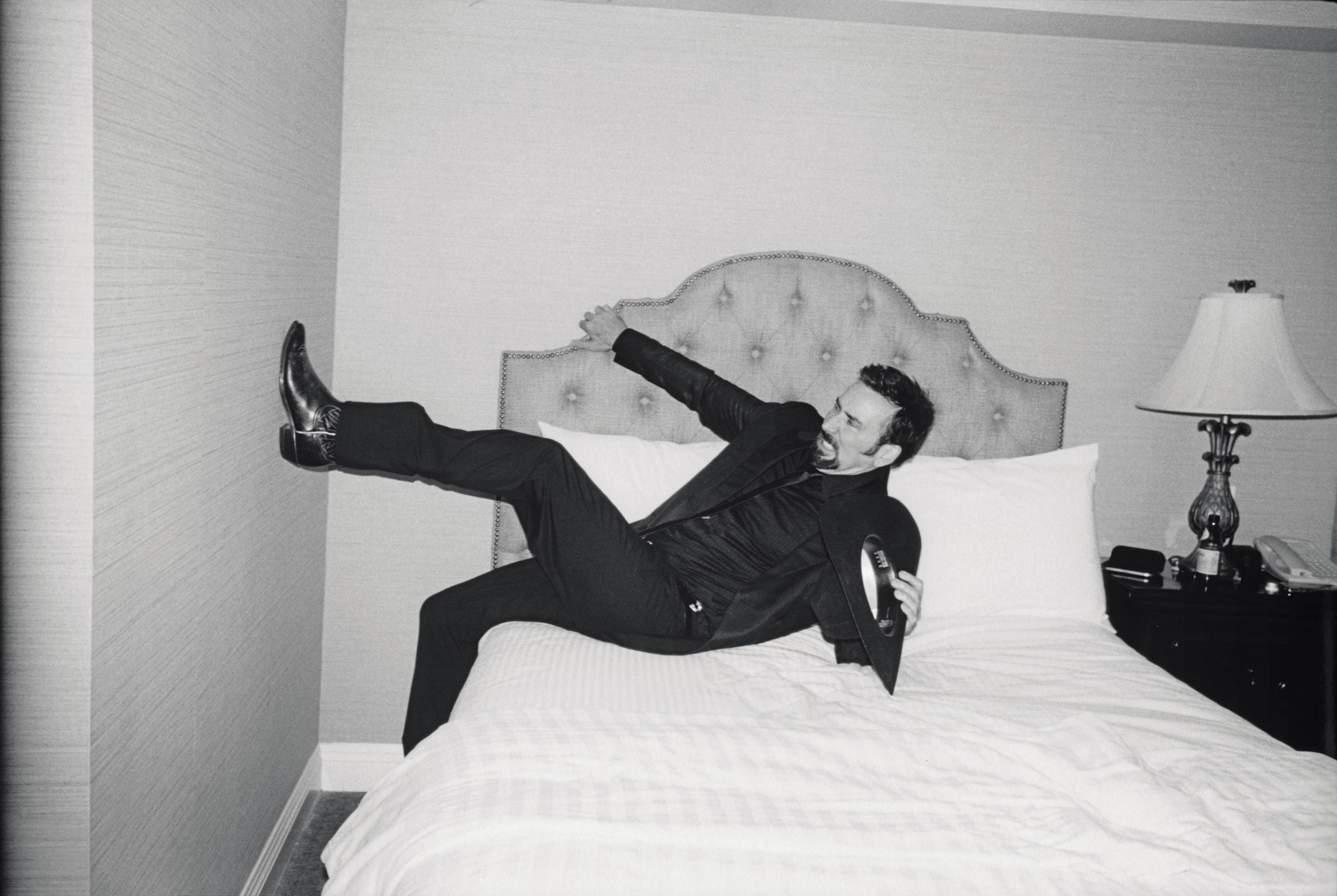

For Document’s Winter/Resort 2023 issue, the horror master and the movie star expound on a possible curriculum for the apocryphal Nicolas Cage University

“He’s probably the only actor who has a perfect film career,” Nicolas Cage says of his hero James Dean, “because he only made three movies. You stay in the game long enough, you have your ups and downs.” Cage has repeatedly cited Dean’s lead performance in East of Eden—which he saw for the first time at age 15—as the impetus behind his own film career. He is famously effusive about his influences, recalling the times he broke down while watching the actor—“I was crying, James Dean was crying”—with the exothermic blend of virility and vulnerability he brings to his performances. Cage had spent the weekend watching YouTube videos of lectures by neuroendocrinology researcher Robert Sapolsky, author of Behave and The Trouble With Testosterone, in preparation for his role as a professor of evolutionary biology in director Kristoffer Borgli’s upcoming film Dream Scenario. “My character is very beta,” he says. “I have my beta moments, too. But he’s very beta. He’s more of a flight guy than a fight guy.” Out of all the roles he’s played, he says this character is least like the real Nicolas Cage. (The most was the alcoholic ex-con in Joe.)

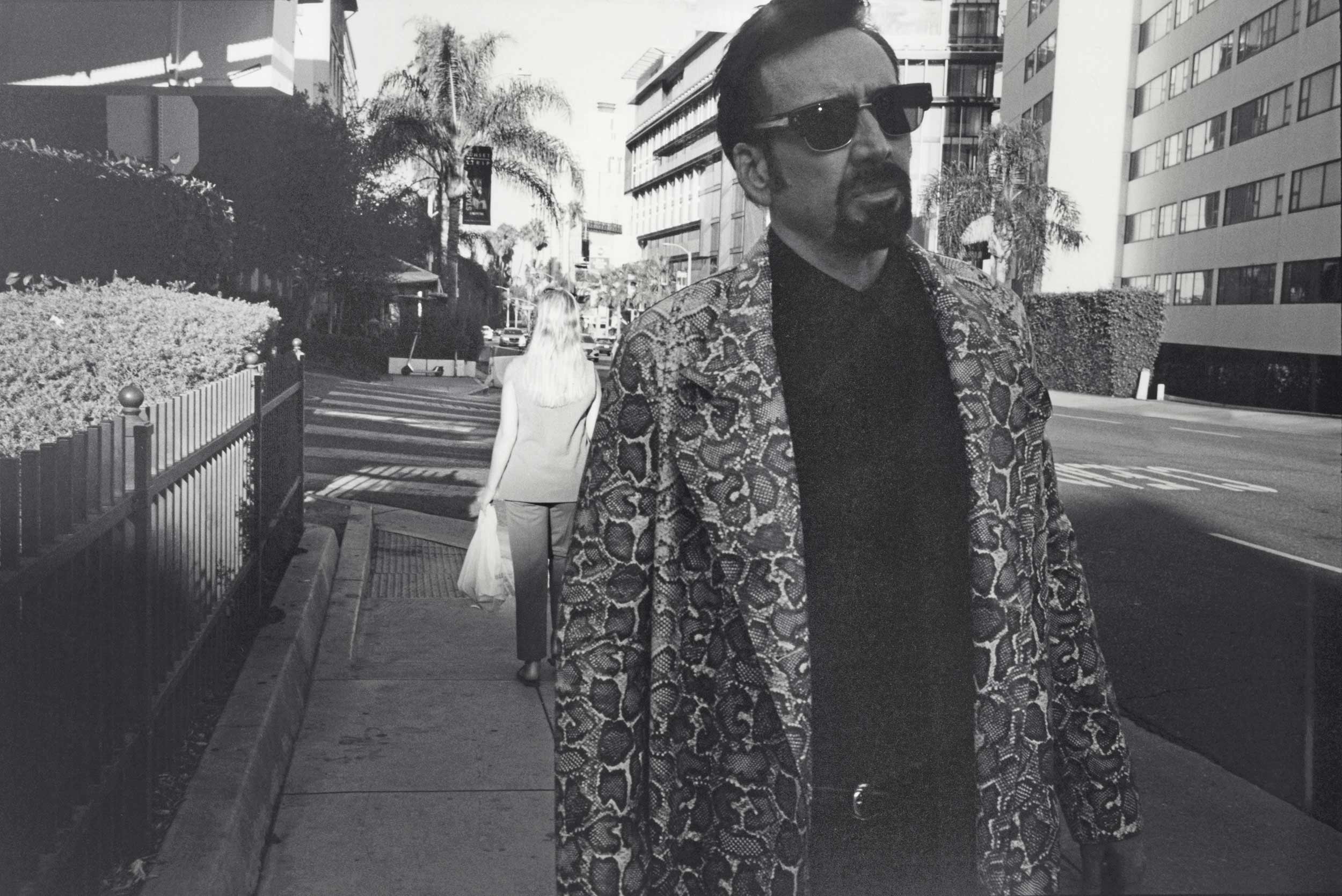

On the face of things, the sprawling, laborious trajectory of Cage’s acting career is the polar opposite of Dean’s brightly, briefly burning flame—the former having made so many films over the past four decades that there are multiple podcasts where fans attempt the daunting feat of simply watching everything he has starred in. In other ways, Cage is a perfect continuation of Dean’s legacy. He might even be America’s last Movie Star—a nouveau-shamanic rebel without a cause for the era of STARZ on Hulu. Cage has deliberately made it his quest to be eclectic, quietly launching his career with a small part in Fast Times at Ridgemont High before taking it on a risky trajectory that has, in many ways, paralleled the evolution of the Hollywood film industry itself—marked by iconic roles in the Coen brothers’ 1987 masterpiece Raising Arizona, the romantic comedy Moonstruck that same year, and the Reaganomics satire Vampire’s Kiss in 1989. He won Best Actor at the Academy Awards for his performance as a down-and-out Hollywood screenwriter in Leaving Las Vegas (1995), and had a lengthy, surprisingly compelling stint as a blockbuster action hero in the late-’90s (The Rock, Con Air, Face/Off) before the industry ostracized him, just as Netflix was shifting from DVD rentals to streaming media and video-on-demand—a term Cage hates. “Anyone who uses the terms ‘video-on-demand’ or ‘straight-to-video,’ in my view, is a dinosaur. Everything has been streaming these days,” he says. “Do I love the church? Do I love Quentin [Tarantino’s] New Beverly Cinema? Of course. Do I want to see every movie in the church? Of course I do. But what’s happened with streaming is that it’s given people a chance to really build their libraries.”

Streaming ushered in a new era for movies that Cage has embraced unflinchingly, in the name of constant reinvention. His recent output is so prolific and eclectic that it warps the algorithm—or, at least, it confuses the way one is supposed to blindly engage with it. The Tomatometer often can’t decide what’s a sleeper hit, a future cult classic, or just lucrative filler—making it possible to experience the joy that comes with discovering a film, and the chance to make up your own mind about whether it’s any good. Despite the ironic tenor of r/onetruegod and #CageClub, Cage fans’ love of the performance—the sheer personality, the enormity of the emotional component—is as sincere as Cage’s is. There’s a line in Pig (2021), Michael Sarnoski’s character study of a disillusioned celebrity chef living a second life as a truffle hunter in the backwoods of Oregon, where Cage tells his partner in crime, “We don’t get a lot of things to really care about.” People don’t really care about Cage’s dinosaur skulls, or his shrinking list of macabre New Orleans properties these days. They love this year’s breathtakingly egocentric action comedy The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, and the bromance at the heart of it. But they care about the harrowing bathroom scene in Panos Cosmatos’s heavy metal-inspired revenge horror Mandy (2018). Cage’s performances in this film and in Pig are forceful but not forced, relying on life experience, on emotional honesty, as much as imagination and craft.

At the age of 74, John Carpenter has reached the only milestone in a man’s movie career that Nicolas Cage will likely never arrive at: retirement. That doesn’t mean the cult filmmaker and pioneering electronic composer behind horror classics like Halloween, They Live, and The Thing has stopped working. Quite the opposite: He is now a full-time musician. In 2015, Carpenter released his debut studio album Lost Themes with the acclaimed indie label Sacred Bones: an amalgamation of sound designed to incite nightmarish, nostalgic visions—“a menacing shape stalking a babysitter, a relentless wall of ghost-filled fog, lightning-fisted kung fu fighters, or a mirror holding the gateway to hell”—in the horror master’s faithful acolytes. More recently, he worked with Daniel Davies and his son Cody Carpenter on the score for Stephen King’s Firestarter: an intense, atmospheric anthology of sci-fi anthems, spine-tingling synths, and reverberating piano ballads that marks the trio’s first official soundtrack outside of the Halloween franchise.

Like Cage, whose Uncle Francis (Ford Coppola) raised him on Beethoven, Bach, and Wagner’s Parsifal, Carpenter grew up in a household permeated with classical music. He was encouraged by his father, a concert violinist and music professor, to learn the violin—a familial fiasco that led to brief attempts at the guitar and piano, and then to an epiphany, when Carpenter heard the soundtrack to the 1956 sci-fi adventure classic Forbidden Planet and discovered electronic music. It was around this same time that his love of monster movies was jump-started by It Came from Outer Space—a pulpy, psychological sci-fi horror released in 1953. Carpenter has claimed that he never cared for German expressionism, Italian neorealism, or Russian montage as much as he does for flops, trash, and gore. But he’s still a student of the silents and classics at heart, with a litany of inspirations that animate him: Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, the atomic creatures in Ishirō Honda’s Godzilla, and, yes, German expressionism—extracting Halloween’s particular feeling of suspense from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu.

Sadly, we never got a Carpenter and Cage film before the former’s retirement. The two share many influences: American Westerns, kaiju eiga, and orchestral music, among others. The horror master and the movie star, still eager students of film at heart, meet over Zoom—Carpenter from his home in Los Angeles and Cage from Toronto, where he is filming Dream Scenario—to expound on a possible cinematic curriculum for the apocryphal Nicolas Cage University.

Nicolas Cage: It’s kind of remarkable to me, after how long we’ve both been doing this adventure in cinema, that this is the first time we’re really talking.

John Carpenter: Well, here we are. How are you doing today, Mr. Cage?

Nicolas: I’m doing really well, because I just had a mini John Carpenter film festival in anticipation of our conversation, which I was extremely knocked out by.

John: I’ve had many Nicolas Cage film festivals—many of them.

Nicolas: Oh, that’s nice to hear. I just finished In the Mouth of Madness, nearly two minutes ago. Boy, you really got me—you really spooked me with that. I hope I’m not going to turn into Sam Neill’s character.

It’s interesting that we’re talking now, because it was only two months ago that Quentin Tarantino suggested I watch Assault on Precinct 13. Remarkably, I hadn’t seen it before. Your score got me thinking about one of my three favorite film composers—well, four, [counting] you: Nino Rota, Akira Ifukube, and Ennio Morricone. You collaborated with Morricone on your masterpiece, The Thing. I want to know what that was like for you.

John: He was a very, very kind man. I flew over to Rome to talk to him. I didn’t speak any Italian. He didn’t speak any English. We had a translator. And he had a few melodies. He played them on the piano, asking me if I liked them. I said yes, but I asked him to do something that had fewer notes—something more simplistic or minimal. He did the main title that way. The rest was his beautiful, orchestral score. He had the real, dark feel of the movie before I did. I was still trying to find the movie; what was this thing? And he had it.

Nicolas: And I know that we share an interest in Ishirō Honda.

John: Yeah, big time. He passed away several years ago. He was [Akira] Kurosawa’s assistant, which is really interesting to me. I don’t see any influence.

Nicolas: When we think about the first assistant director, we don’t really understand it in the same terms that they do in Japan. In Japan, a first assistant director—if the director needs a break—goes in and cuts and all that stuff. It’s a completely different set of skills. Kurosawa got all the credibility, because of his huge contribution to cinema, but I don’t think Honda got the same level of reverence and regard, because his movies were so popular. I really liked the more obscure ones, like Matango.

John: That’s maybe his best—the mushroom people! I love that movie.

Nicolas: That freaked me out as a kid. I saw it on TV and I’m still recovering—kind of like the way I feel right now, with In the Mouth of Madness.

John: Now, let me ask you, what are you a professor of in [Dream Scenario]?

Nicolas: Evolutionary biology. So, things like adaptive strategies. Why do zebras have spots? The things people don’t really talk about.

John: How do you play this guy?

Nicolas: Well, I didn’t have much to do in terms of research, because I was raised by a professor. My father was a scholar of comparative literature, when he was still with us. But he was also very active in the arts. He’s the real reason I got into movies, because he would show me stuff like Citizen Kane. He was the one who fomented my interest in expressionistic acting, such as Nosferatu, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. And even earlier, with folks like [Charlie] Chaplin and [Buster] Keaton.

John: So it’s second nature to you?

Nicolas: I remember seeing him teach at Cal State Long Beach, and I recall his moves.

But I’m also looking at [Robert] Sapolsky, and watching some of his YouTube videos—giving lectures, pacing back and forth as he’s talking. But I have a very different look in the movie. My character is very beta. I have my beta moments, too. But he’s very beta. He’s more of a flight guy than a fight guy.

John: Who’s the character you’ve played who was furthest from you?

Nicolas: The character I think was the most like me was from a movie called Joe. I felt like there was no acting, outside of a little bit of a rural accent. But the one I think is furthest from me would probably be the one I’m doing now in Dream Scenario. And perhaps Adaptation.

John: Acting is such a hard thing for me to figure out, because I can’t do it. I don’t understand you guys—but I direct you guys, and I enjoy it. How you get where you need to be is fascinating to me.

Nicolas: I think there is an element of mystery to it, even for those of us who act. You can prepare, and you can design with the exterior—what the moves are, what the look is, how this person dresses, how this person speaks. I think the first question we ask—What does the character want in every scene?—that’s sort of the doorway in. But the other stuff, the stuff that informs all the outward design, that’s the mystery. It’s almost like we don’t want to talk about it, because there’s a little element of magic to that.

John: That’s exactly what it is. It’s magic.

“Nothing [else] affected me that deeply; it wasn’t music, it wasn’t painting, it wasn’t books—it was film performance.”

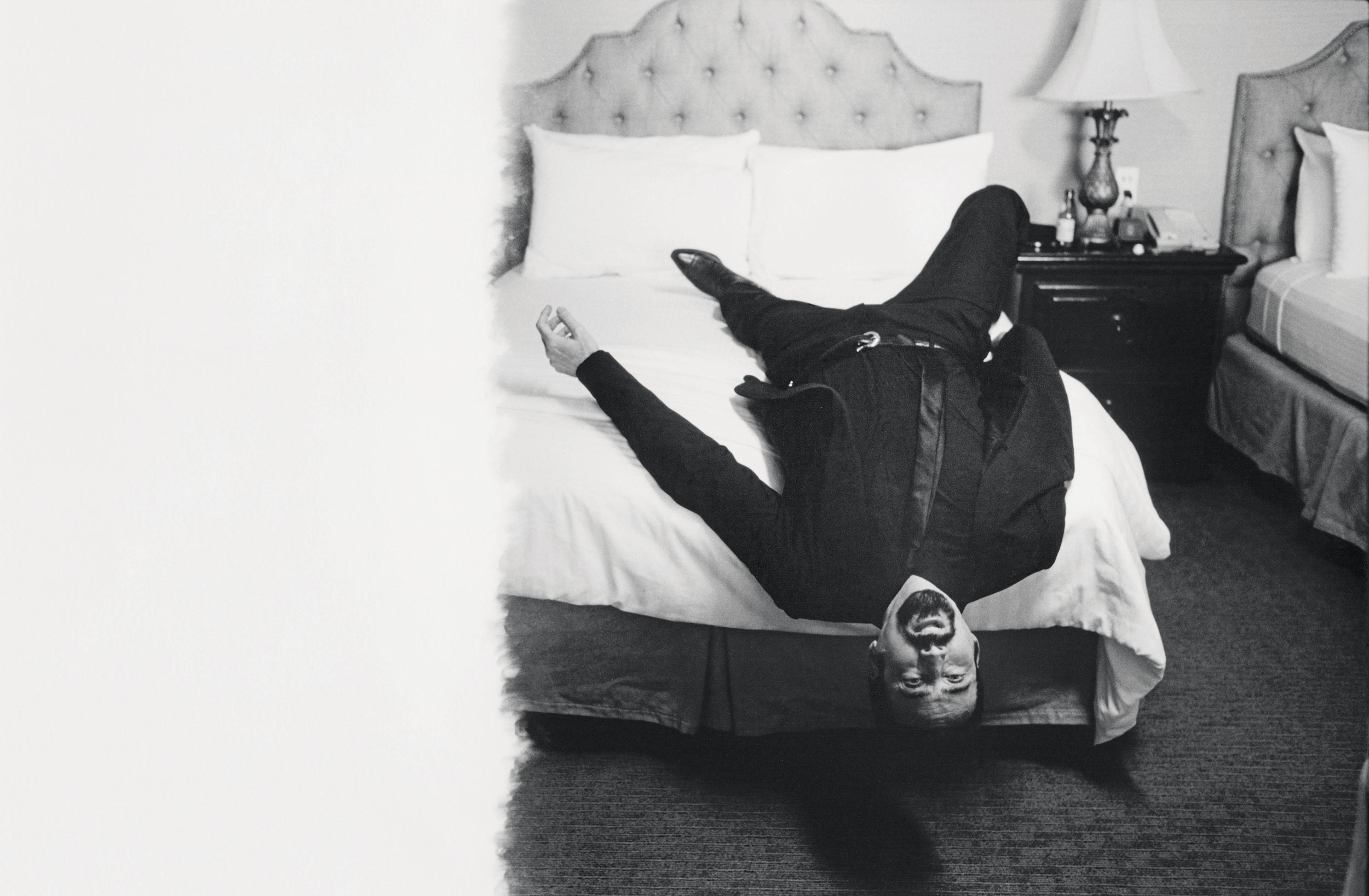

Nicolas: There’s recall, and there’s imagination. [In] Mandy, they had that scene where I have a meltdown in the bathroom, and I had to have an idea of what I was going to recall in my own life—but don’t dive into it too much. Because if you do, it’s like you let the genie out of the bottle. You gotta surf that emotion until the director calls action, and then you let it out.

John: You eviscerate it if you get too much into it. You have to let it bubble. And then let it go.

Nicolas: It seems like everyone has been influenced by you on some level, being the pioneer that you are. But there are two movies I made recently that—if you go through my retrospective of your work—had to be informed by your concepts. One was Prisoners of the Ghostland, where I [wear] a suit that has bombs on it. And if anything goes wrong, they’re gonna light me up. And I thought, Well, that’s got to be John from Escape from New York.

The other was Color Out of Space, which was an interpretation of H.P. Lovecraft. When I was watching The Thing last night, I looked at the sequence with the dogs, where they’re transforming in the holding area; there’s a shot in Color Out of Space where I’m shooting these transforming alpacas, and they used in-camera effects they borrowed from [The Thing]. I think they were trying to achieve that effect, of the huskies transforming—only, in this case, with alpacas. And I’m having a nervous breakdown as I’m blowing them away with my shotgun.

John: I love Color Out of Space. It’s an incredible story, transforming alpacas.

Hey, now listen, Mr. Cage—tell me some of your favorite movies. What do you love in cinema? Where do you go?

Nicolas: I think Elia Kazan was a big reason why I became an actor. I had my heart pulled out by James Dean in East of Eden, in the scene where he was trying to get his father, played by Raymond Massey, the beans for his birthday, and he’s rejected. I was 15, at the New Beverly Cinema. I made my decision right then and there—that is what I wanted to do. Because I was crying, James Dean was crying. Nothing [else] affected me that deeply; it wasn’t music, it wasn’t painting, it wasn’t books—it was film performance.

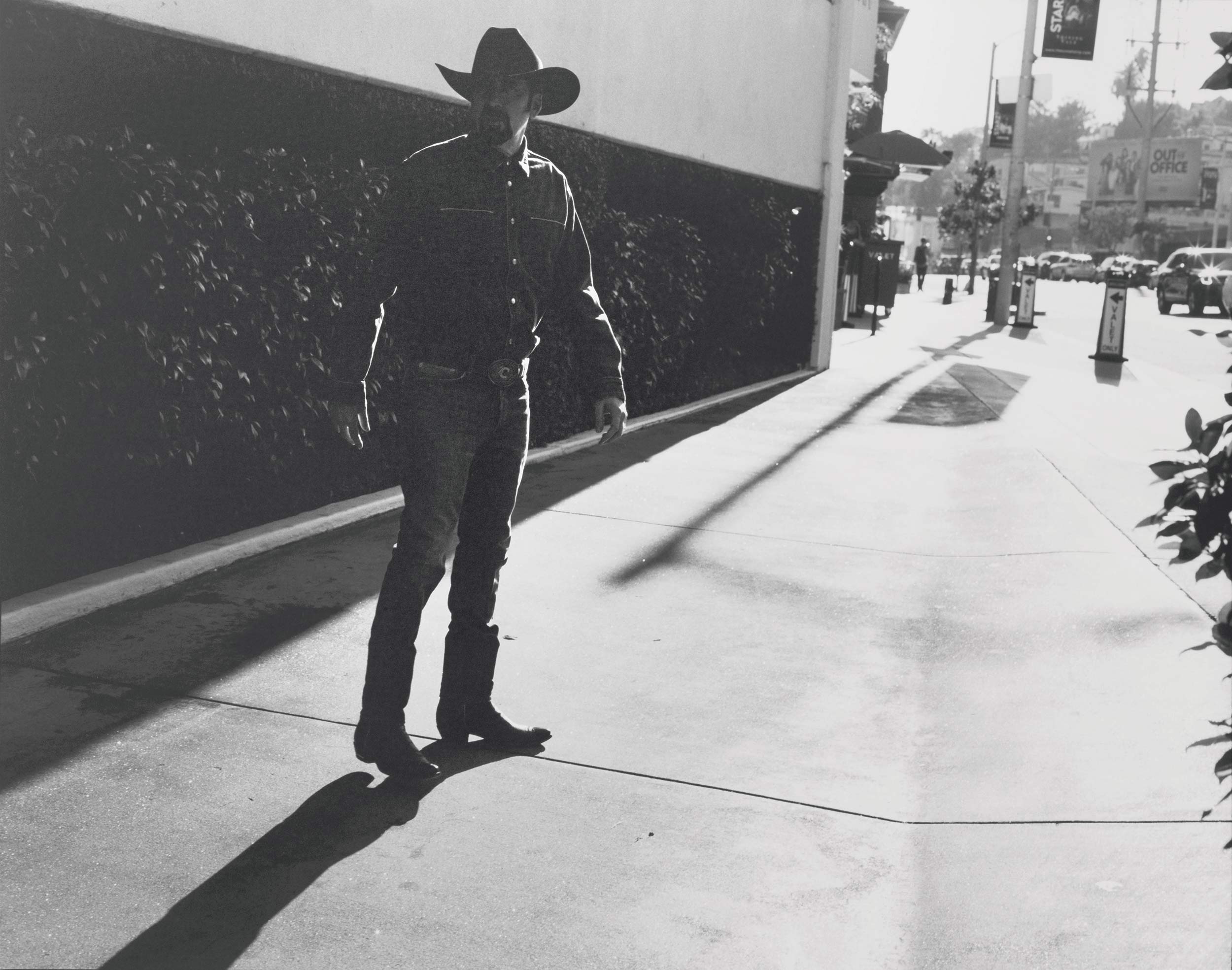

So the base is that: independently spirited drama. But being eclectic, I’ve wanted to branch out. I grew up watching Charles Bronson in movies like Mr. Majestyk, Once Upon a Time in the West, and Hard Times. I think people need to reevaluate Bronson’s contribution. I think he got a little sidetracked—but what he was able to accomplish was hard to do. He had that stoicism that was deeply, deeply poignant. On the other side of that, you have Bruce Lee. It was the first time I saw somebody do something on camera where I thought, Superheroes do exist.

But it goes on and on, John… I wouldn’t be able to put them all on one list. It’s hard. Movies are like seasons. I mean, how do you feel about Citizen Kane? I think that’s still probably the greatest movie ever made—or at least top two, or top five.

John: Well, Citizen Kane is still a tour de force of innovation. Orson Welles—in that movie, he was a genius. But I also love his other films. Check out Touch of Evil.

Nicolas: Oh, man.

John: Underrated movie.

Nicolas: Well, it’s the greatest opening shot ever. It just keeps going. It’s a dance.

John: You come at movies from the performance point of view. I never look at [them] that way, although I notice the acting. I understand what it is you like about East of Eden. And James Dean—too bad he was taken from us so early. Man, he had potential.

Nicolas: But where would he have gone? What would that have been like? I mean, he’s probably the only actor, John, who has a perfect film career. Because he only made three movies. You stay in the game long enough, you have your ups and downs.

John: Everybody does. It’s interesting. How would he have been, if he matured as an actor and explored other things? I have no idea.

Nicolas: I would like to think that he would have been a kindred spirit, and that he would have hopscotched different genres, and been eclectic, and tried different things.

John: I think you’re the most… How can I put this? The bravest actor I’ve ever known. You try things, you don’t stop.

Nicolas: Thank you.

John: It is unbelievable. A new movie with a new idea and a new character, and here he is again. He’s going out there one more time. I mean, you love living on the edge of this performance stuff. Putting it out there. I just stay in my box. I enjoy myself here.

Nicolas: I get it. But it would be fantastic to see more of your movies, you know?

John: Well, I’m making music now, Nicolas.

Nicolas: Yeah, the music is powerful. It really is. I always loved electronic music.

John: Have you?

Nicolas: Well, I grew up watching [Stanley] Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Wendy Carlos, what she was able to do with Bach, was so magnificent. And I’ve always had an interest in electronica. When I heard your score for Assault on Precinct 13, I was extremely knocked out—you get so much out of it. And that’s the thing: You directing that movie, it’s one of the few times, really, where the video image and the audio image link up perfectly.

John: You’re very kind.

“I think you’re the most… How can I put this? The bravest actor I’ve ever known. You try things, you don’t stop.”

Nicolas: I’m not trying to be superfluous, or hyperbolic. This is an actual fact. I think more directors should learn from what you’re doing. Jerry Lewis used to say to me—he was my neighbor at one time—‘I want you to be the Total Filmmaker.’ And to be the Total Filmmaker, you have to write your own music, you have to act, you have to direct. What you’re doing is closer to the Total Filmmaker than most, you know? But you gotta star in it now.

John: [Laughs] I don’t want to burst your bubble on Assault. But let me tell you: I had one day to do that score.

Nicolas: Well, that’s perfect! Didn’t Paul McCartney write ‘Yesterday’ in one day? Did you see that Disney+ documentary? When he’s coming up with ‘Get Back’? It’s like he’s taking it out of the ether. When it’s there, it’s there. It doesn’t need a million years.

John: Well, that’s true. You’re nice about it—but it had to be simple, because I couldn’t do much more than that.

What’s coming up in the future?

Nicolas: Well, the movie I’m doing now—I would put that in the unquantifiable zone between drama and comedy. But then I’m going back to genre; I’m gonna do a movie called Sand and Stones. I play a father in that, with twin sons. It’s kind of a post-apocalyptic [survival] situation. After that, I’m working with Oz [Perkins], who you probably know.

John: No, I don’t.

Nicolas: He’s pretty strong in the horror genre at the moment. But he’s actually Anthony [Perkins’s] son. He’s done some really good movies. Gretel and Hansel was terrific. It’s about a character who’s hearing voices. It’s kind of like a possessed Geppetto, who’s making these dolls—

John: [Laughs] I like it. Possessed Geppetto. Man, oh man.

Nicolas: So, I’m gonna be doing that with Oz, who’s also an actor, and I’m excited about that. I told him that I thought Anthony Perkins was in the same club, in some ways, as James Dean and Montgomery Clift—but that his dad was spookier. There was this strange tension under him that made him a little more edgy than the other two. Especially, you know, when you see him in movies like Psycho.

John: Anthony Perkins was a really kind, kind man, and he had a lot of talent. Did you ever meet him?

Nicolas: I never met him. But I’d love to hear about him.

John: Back in the day, Burt Reynolds, when he was riding high, used to throw these parties. I went to one, and it was pretty incredible. They had a game of charades, and Anthony Perkins and I teamed up, and we were perfect. We beat everybody, hands down. Because we had the same brain. I could come up with one gesture, and he had what it was.

Nicolas: Well, you know what that means, then, John? That means that you’re also an actor.

John: [Laughs] No, no, no.

Nicolas: Well, yeah. To communicate through a gesture and get it… Let’s say you have a child, and you want to know if they can act—give them a toy phone, and see what they sound like when they’re pretending they’re on the phone with somebody.

John: You ought to teach a class, Nicolas. What do you think?

Nicolas: I’ve thought about it. I think it’s time to start giving back in some way. If I did have a class, I would make it very Socratic. I would not be one of those guys who is a tyrant of a teacher. I would ask them questions. I would make it an open conversation. And I would get into different things that I’ve tried that helped me get there.

John: I like it. You know, what we could do—if you want to be a grifter with me—we could do something like Trump University. We could do Nicolas Cage University. What do you think?

Nicolas: Well, I mean, I don’t know if I’m ready for that. Maybe down the road. I think I’d rather make a movie with you.

John: We could grift some bucks off of people.

Nicolas: I don’t know about that one, John.

John: I want you to consider Nicolas Cage University.

I want you to think about it.

Nicolas: Yeah, with a little In the Mouth of Madness energy thrown in [laughs].

John: Yeah, that’s it.

Groomer Pamela Warden using Dior Sauvage Face & Beard Moisturizer. Photo Assistants Mitchell Stafford, Dean Podmore, Colin Smith. Styling Assistants James Kelley, Taylor Hubbard. Production Madeleine Kiersztan at Ms4 Production. On-set Producer Lisha Sun. Production Assistants Kendy Lee, Marina Dallokken, Steven Zhang. Talent Director Tom Macklin. Shot at The Sunset Tower and Best Western Plus Sunset Plaza Hotel. Handprinting Natalie Hail. Retouching October.