The London-based photographer joins Document to discuss the spontaneity of his creative process, the alluring appeal of analog, and finding inspiration in an image-saturated age

“I’m drawn to singular images,” says London-based photographer Jack Davison. “The subject, style, and format can shift, but photographs that can hold my gaze are the ones I come back to most.”

Davison is, himself, a creator of such images: photos with the power to stop you in your tracks, requiring a second look to decode the mystery of their composition. In his work, light and shadow interplay, illuminating and obscuring in equal measure; arresting details catch one’s eye, while large swaths of black awaken the imagination. This elusive quality is intentional: In presenting some aspects and obscuring others, Davison aims to invoke the viewer’s subconscious, resulting in photographs that often reveal more about the person viewing them than they do their subject. “I leave space for the viewer’s own imagination, thoughts, and prejudices… There needs to be a window for someone else to step in and bring their own viewpoint,” he tells Document. “My hope is that the less I give you, the more you will bring to it.”

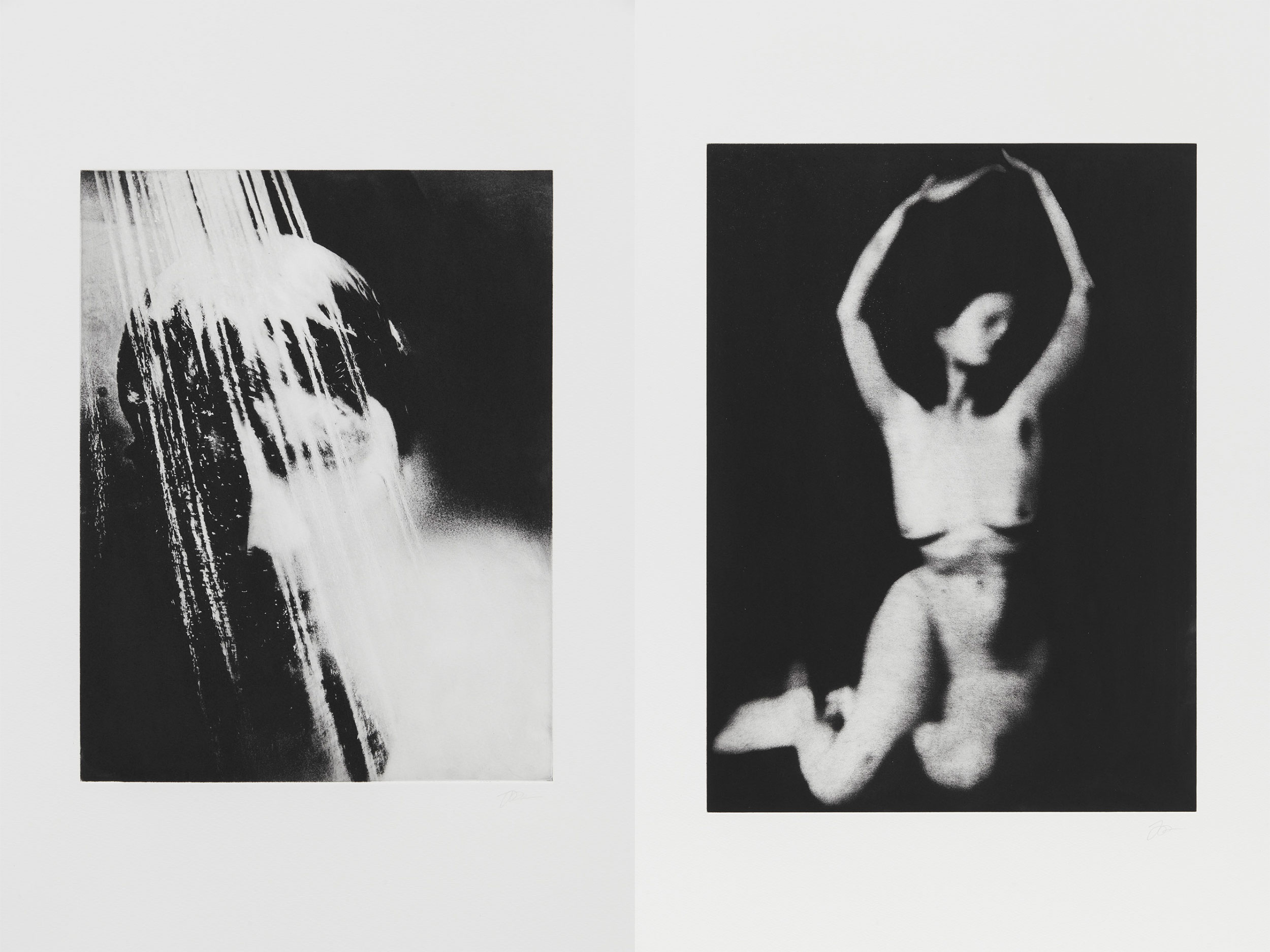

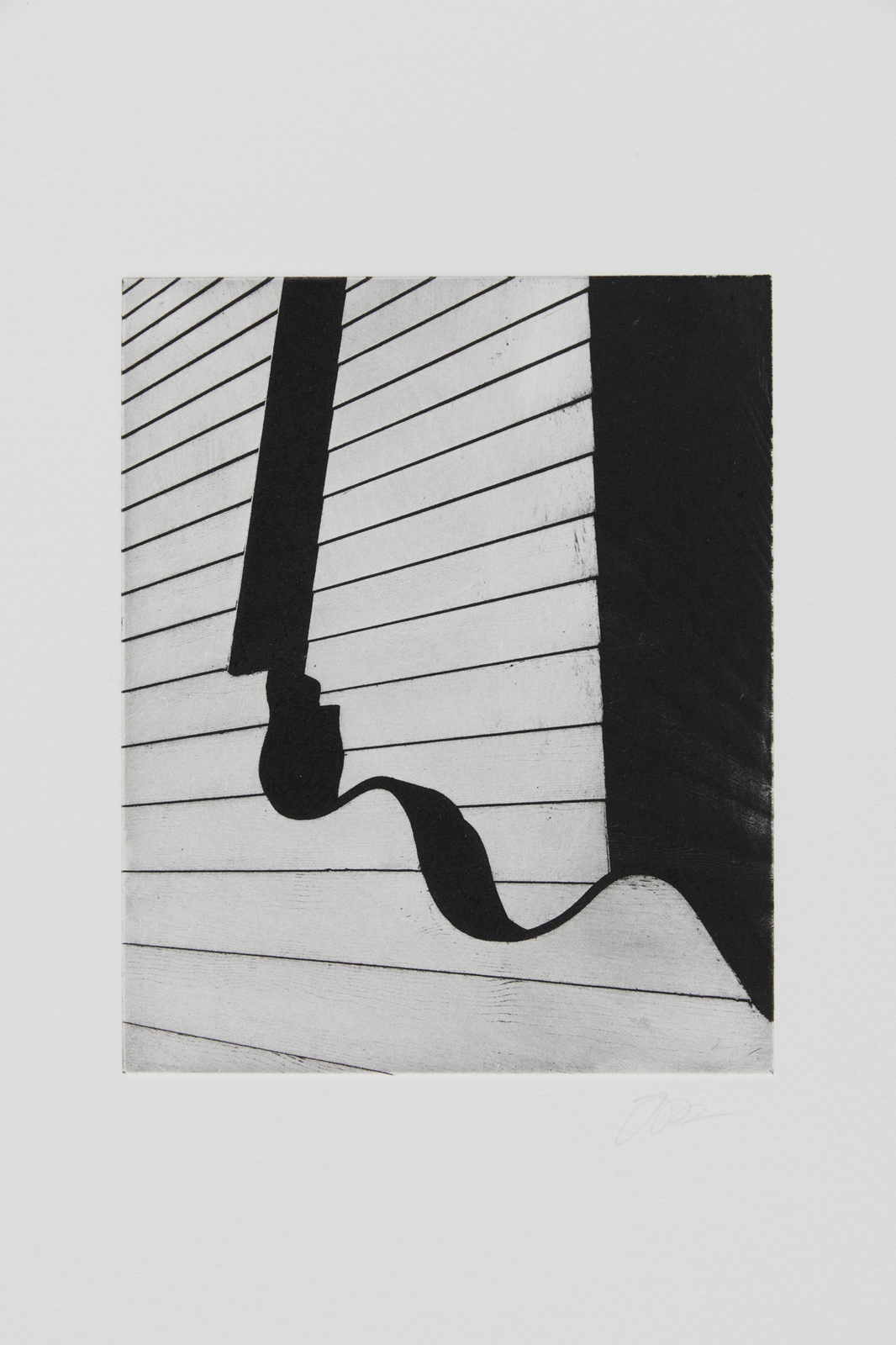

Despite an upbringing spent making digital images, Davison has a deep appreciation for the physical ephemera of the medium: the “dog-eared photo manuals, found family snaps, and thumb-stained pictures” that ground his craft in the material world. It’s why his latest exhibition, Photographic Etchings, sees him dive deep into the tactile aspects of image-making through traditional processes. “Printing by hand is really rewarding, because it brings you closer to the image and the ink,” he says. “The process itself pushes you further into abstraction.”

This sense of mystery—of something left unsaid, obfuscated, or outside of the frame—imbues the works in the show with a dreamlike, transient quality. Ongoing motifs like hands, eyes, and the bared teeth of snarling dogs repeatedly surface, yet seem to exist outside of context and time. Tight framing and deep shadows lend a sense of sinister surrealism to what would otherwise be straightforward: a woman stretching, a man’s face, the facade of a building. “I’ve always been drawn to photographers that push the medium to do startling things,” Davison says, speaking of the kind of image he gravitates toward. “I quite like feeling the heavy hand of the author at play.”

Davison’s work has appeared on the cover of Document Journal and other publications, including The New York Times Magazine, W Magazine, and British Vogue. In 2019, his first monograph Photographs was published by Loose Joints, and this year, he released another book, Song Flowers, in collaboration with Loose Joints and Marni. In the wake of his recent exhibition Photographic Etchings at London’s Cob Gallery, the photographer joins Document to discuss his process, inspirations, and advice for making photographs in an image-saturated age.

Camille Sojit Pejcha: The images for your show at Cob Gallery have been traditionally hand-printed. What’s your relationship with the tactile, physical aspects of photography, compared with the more conceptual or intellectual aspects of art-making?

Jack Davison: I try to not conceptualize my practice very much; I find that often an image can feel much less spontaneous and emotive for me if I’m overthinking. I work both with film and digital, but was raised making photographs on my laptop. Despite that, I’ve always had a love for physical ephemera: dog-eared photo manuals, found family snaps, and thumb stained photographs. Printing by hand is really rewarding, because it brings you closer to the image and the ink. You expose a photograph onto a metal plate and then print from that plate directly onto the paper, so it’s closer to a traditional etching than a typical photograph. It’s fun to experiment with the form—the process itself pushes you further into abstraction.

Camille: I’ve read that your work was formatively shaped by online platforms like Flickr and Tumblr. Can you tell me a little bit about this era of your life?

Jack: I was a countryside kid, with patchy internet and not much access to photography outside of that. By chance, I started posting on Flickr, and through that found a community of photographers who were infatuated with daily image-making. It was exhilarating. I could have conversations through pictures with people all over the world instantly, and we’d react to each other’s work—it was all very organic and it really encouraged experimentation and play.

Camille: Having come of age online, how has the proliferation of digital images affected your own creative evolution and what you aim to do as a photographer?

Jack: I wouldn’t say it’s necessarily a negative thing, though there are definitely downsides to our rapid consumption of imagery—cycles of repetition that aren’t helped by algorithms, for instance. A lot of that proliferation encouraged me to be creative, and to take risks and really focus on finishing a photograph: making sure it was strong and singular, and could hold its own if I posted it. I still remember the excitement I had at that stage for working on a photograph, posting it, and the electric feel of it disappearing off into the world. Flickr, Tumblr, Instagram and the like all come and go, but they still remain exciting places to have that instant exchange with people that just wasn’t available before the digital age.

Camille: A lot of your images simultaneously reveal and conceal the subject, pulling some details to the fore and obscuring others through light and shadow. Can you tell me a little about your path to this form of image-making? How did you discover that images can communicate more by showing less?

Jack: To be honest, a lot of the path to finding my practice has been making lots of mistakes, and through those mistakes, realizing the kind of work that you want to make and what excites you the most. For me, that’s imagery that is stylized, with heavy blacks and strong colors. I’ve always been drawn to photographers that push the medium to do startling things. I quite like feeling the heavy hand of the author at play.

Brett Walker, who tutored me early on, always encouraged us to remove anything from the frame that wasn’t important or was distracting, and to really focus on our cropping. And over time, I’ve realized that you can say just as much without providing the full context of the scene, and that simplicity can be quite powerful.

Camille: Your work mines the tension between perception and imagination, leaving a lot open to the viewer’s interpretation. How does the idea of subconscious symbolism—dreams, Rorschach inkblots, and the like—inform your approach to photography, if at all?

Jack: It’s always interesting to see what people read into my work; this idea is never something I am consciously pursuing, but I could definitely see it as a throughline to read my work. What’s important is that I leave space for the viewer’s own imagination, thoughts, and prejudices to flourish. There needs to be a window for someone else to step in and bring their own viewpoint. If I give you all the context and my version to the fore then there is a lot less space for nuance, hence why nothing is titled or captioned in the exhibition. My hope is that the less I give you, the more you will bring to it.

Camille: What is the role of chance in your creative process? What about mistakes, human error, intuition?

Jack: It definitely plays a huge role in many of my favorite photographs. As much as I can have control over a situation, the best things often come to you spontaneously and are totally unplanned. This could be a person walking into frame, the randomness of someone’s movement, or the way the sun can shift and change a space. The most important thing you can do as a young photographer, artist, or musician is give yourself room to experiment and stumble into mistakes as they will teach you just as much as your successes.

Camille: I read that as a photographer, you’re largely self-taught. How did you hone your eye? Do you think the results would have been different, had you come upon photography through formal training?

Jack: Who knows, to be honest! I feel very fortunate to have found my way to the industry via an English degree, having escaped the formal training route. I don’t think there’s any correct pathway though, and I am sure I would have loved studying photography.

The only thing I will say though is that when I meet students, they often over-theorize, and aren’t taking as many photographs because they feel they need to justify it. That’s always my first question to people starting out: how many photographs are they taking?

Camille: If you had to give one piece of advice to aspiring artists, what would it be—and has that advice changed in today’s technological landscape?

Jack: I always deliver with my advice with a caveat, which is, please feel free to ignore it. Not all advice is universal, and things that have worked for me don’t always have to apply to someone else. With that in mind, here is a bit of a list that I always hold in my head.

Take lots of photographs, hundreds and hundreds. If you want to make color photographs, photograph color. Always be polite and kind. Don’t be pompous. Shoot on everything and anything—iPhone, digital, film, it doesn’t matter what made it, as long as you’re pushing yourself to create. Don’t look at what work is being made now, look further back and outside of the industry for your inspiration—and good research is really important. Also, there is no rush, despite what Instagram presents to you. You are much better off taking your time, because one strong project is better than three rushed ones.

Camille: What, to you, makes for a compelling image?

Jack: I am really drawn to singular images that can stand alone. The subject, style and format can shift, but photographs that can hold my gaze are the ones I come back to most.

Jack Davison’s latest exhibition, Photographic Etchings is on view through November 12 at Cob Gallery in London.