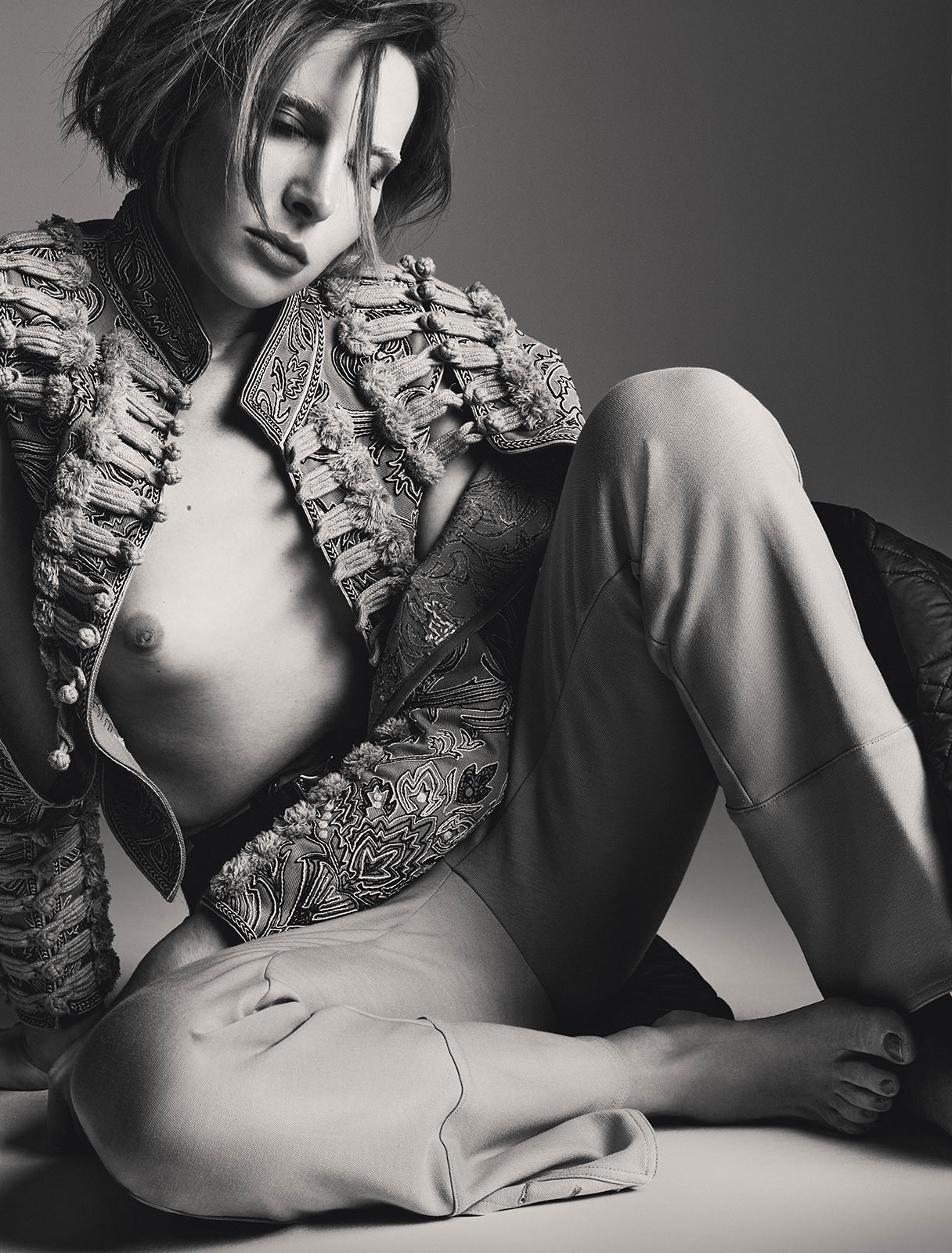

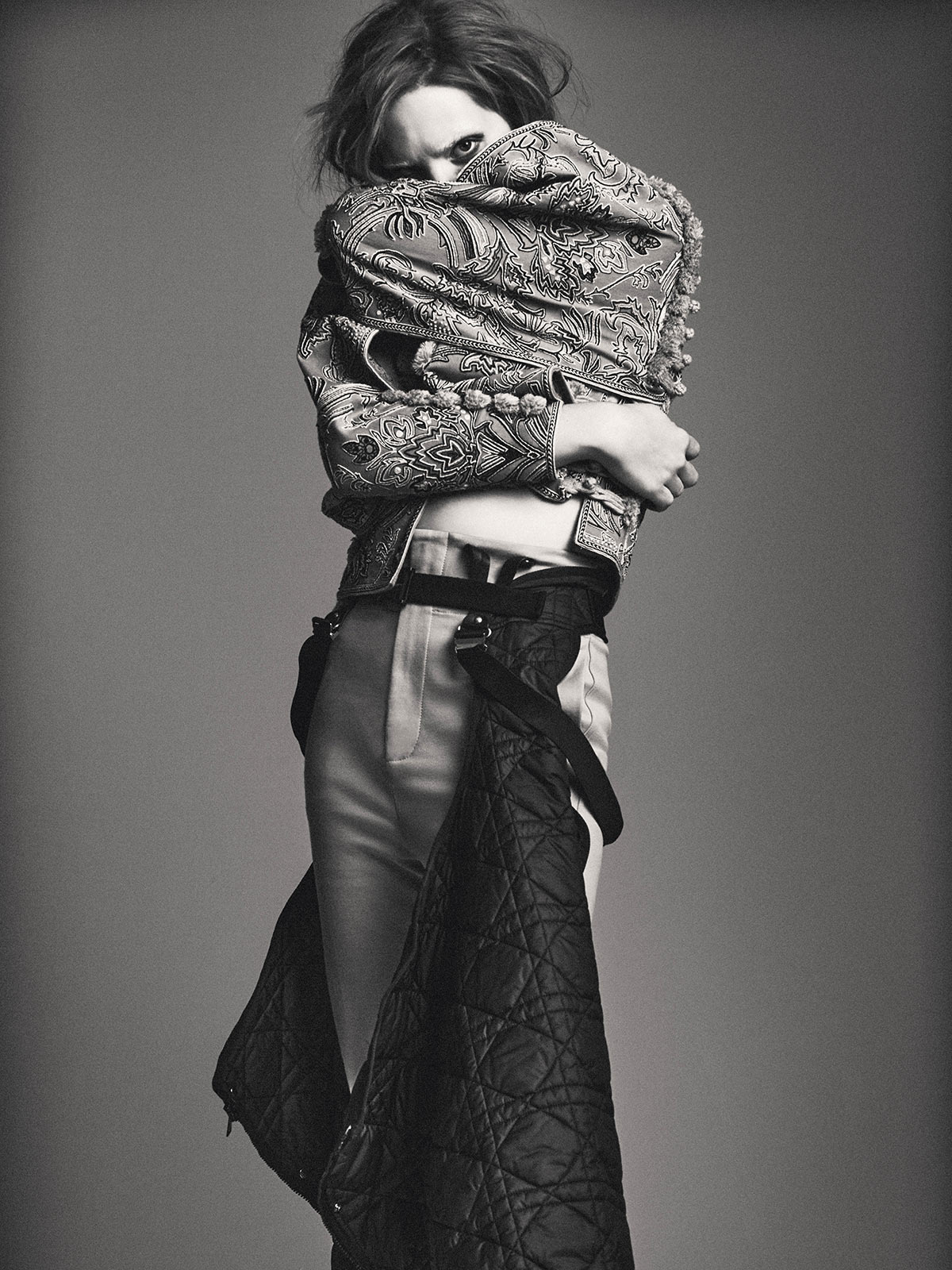

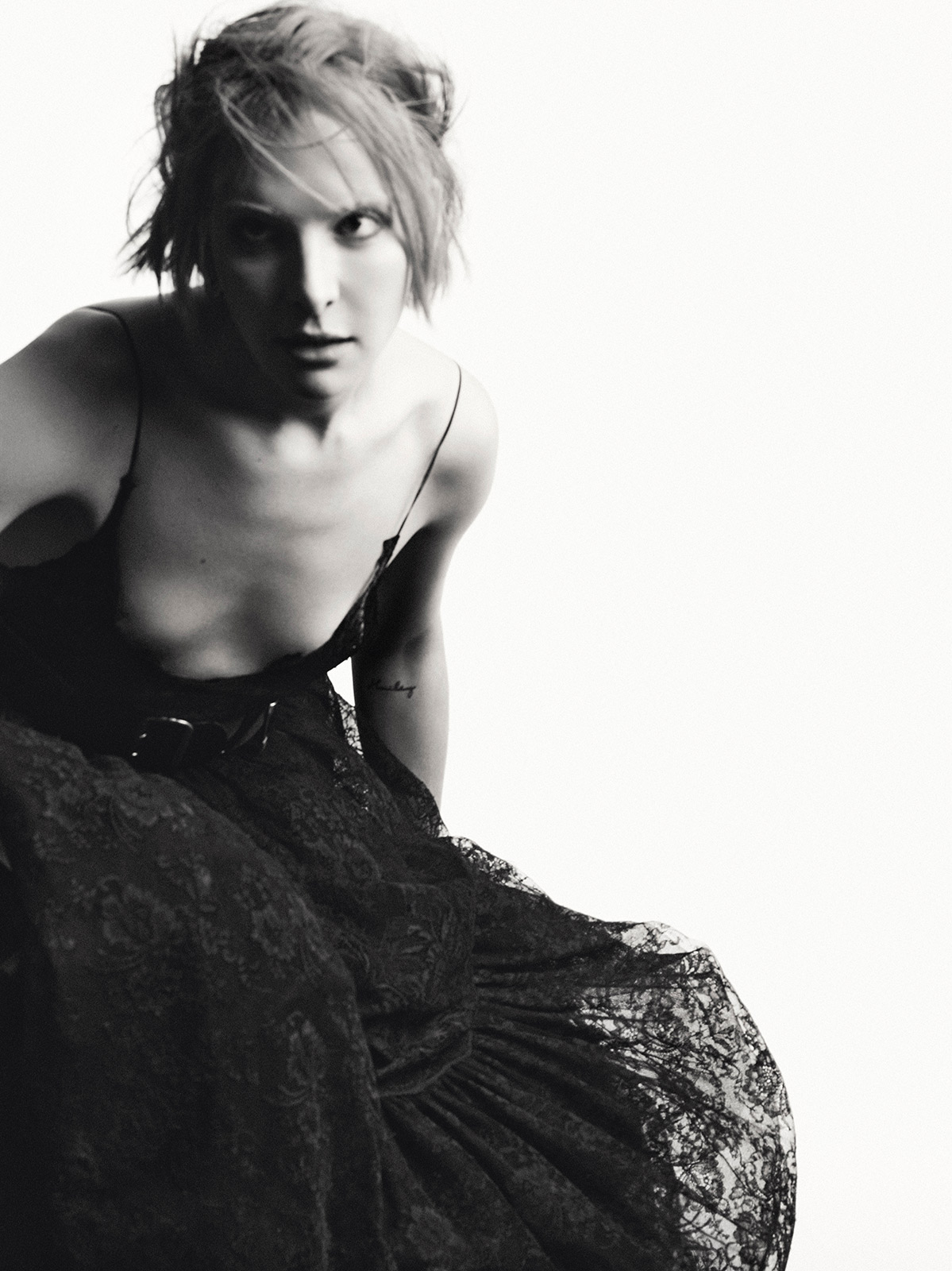

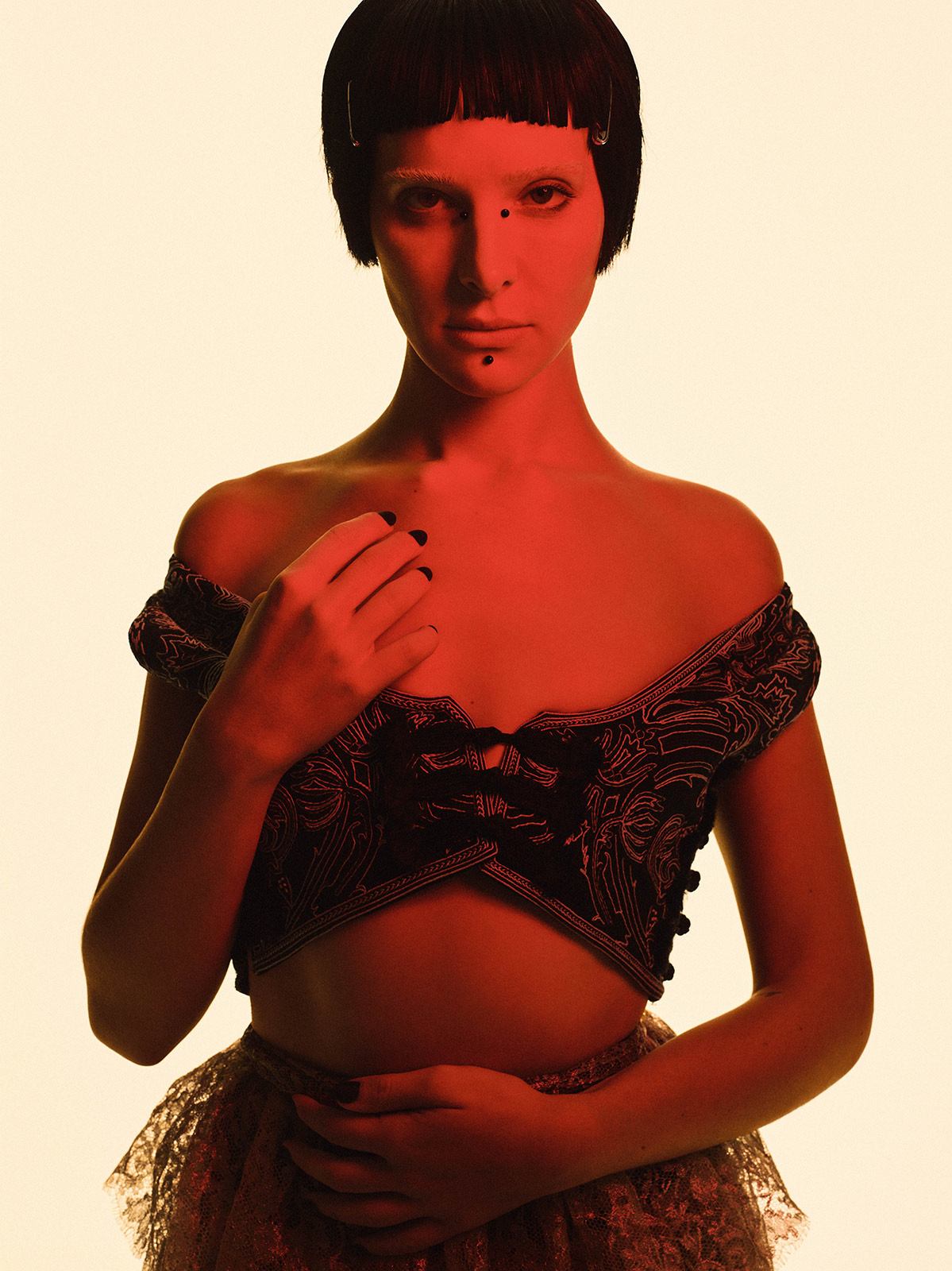

For Document’s Winter/Resort 2023 issue, the actor and writer reunite in the name of authenticity—delving into their respective cults of personality

“I know who my people are,” says Hari Nef from her New York apartment, over Zoom at 8 a.m. “People who I love, who I built my life with—who I have friendships and sex and relationships with… There are probably a couple thousand people in this world I will ever feel that way about.” A couple thousand meaningful bonds, of course, might seem like plenty to the average individual. But Nef is far from average—and, generally, out and about to a greater degree than the rest of us.

The downtown personality-turned-model-turned-actor shot two films this year—including Greta Gerwig’s highly anticipated dramedy Barbie—a television series, and a pilot. She’s set to portray Candy Darling in an upcoming biopic. She walked nine runways at Spring/Summer 2023’s Fashion Month, dutifully showing face at all of the relevant parties. Now, she’s preparing for an off-Broadway production—Des Moines, by the late Denis Johnson—and at the time of our interview, she’s on the brink of running late to rehearsals. The play is set in a seedy Iowan residence, on the evening following Daylight Saving Time’s end. It features a band of unlikely characters, who come together for a night of chance communion: karaoke, liquor, and stream-of-consciousness musings on life and death. “What I write about,” Johnson once explained, “is really the dilemma of living in a fallen world and asking why it is like this if there’s supposed to be a God.”

Nef can say this much, at least, on the Church of Entertainment: “People want to know that you’re a good little soldier of God.” The actor first came to prominence in 2015, as a fresh-faced Columbia grad with an affinity for performance art, Twitter, and the diaristic essay. That year, she signed to IMG—becoming the mega-agency’s first openly trans model—and accepted a role in Prime Video’s acclaimed series Transparent, for which she earned a 2016 SAG Award nomination. “If you’re coming to the table as a woman, or anything else, people want to know that they can trust you,” Nef says, on gaining the acceptance of film and fashion’s ruling class. “People want to know that you’re going to keep their secrets.”

Such is the line any up-and-coming starlet must toe: bringing something new to the table, without tipping the boat all the way over—at least, not all at once. On her side, Nef has the allure, the persona, the intellect, the glamor. But bolstering everything else is her sure sense of control, which translates to sense of self; it’s control that’s rooted, ironically, in the knowledge that it can’t be exerted in certain spheres. “I can’t control how I’m seen,” she offers. “I don’t care where somebody who doesn’t know me thinks I belong.”

Lena Dunham is an expert at this particular manner of worldview. The iconic writer, actor, producer, and director is cemented in pop culture’s history books, best-known for Girls—the hit HBO series, which follows a group of complicated white women who live and date and make questionable decisions in and around Brooklyn. The show has been proffered as the millennial woman’s answer to Sex and the City. (Nef guest-starred in the latter’s reboot, And Just Like That…, as Rabbi Jen, who Charlotte hires to officiate her child Rock’s gender-neutral “they-mitzvah.”) There isn’t, up to now, an acceptable Gen Z Girls comparison—but that’s sort of the point. The show featured a coming-of-age narrative that’s exceptionally narrow, in a way that things just aren’t anymore—to its great benefit, and simultaneously, its detriment. It was a groundbreaking exercise in complicating the figure of the heroine, a slice of privileged life in New York City, and an of-its-time segue to hundreds of conversations and think pieces and online debates about which sorts of lives are broadcast to mass media, and why.

Dunham is a close friend of Nef’s, and a frequent collaborator. She refers to the actor as her “self-help guru,” a “LiveJournal-Tumblr queen,” a “Shakespearean smarty who’s thinking in theory.” In some ways, the pair’s relationship is akin to that of a mentor and mentee, where those roles are swapped freely over the course of a given conversation. What allows this exchange is some kind of humility, or a lack of seriousness, or maybe, a dedication to something that’s often chased in the realm of celebrity, but rarely ever actually achieved. It’s a quality at once demanded and punished, claimed and denied, hard to fake and yet faked all the time: realness.

For Document, Nef and Dunham come together in the name of authenticity—delving into their respective cults of personality, touching upon heartbreak, Instagram, astrology, writing, capitalism, and Hollywood in the process.

Lena Dunham: Hi, Harla. I’m so happy to see you. Where do we find Hari Nef right now?

Hari Nef: I’m in New York, in my apartment.

Lena: And you’re heading to rehearsal?

Hari: Yeah, for Des Moines—this play that I’m doing by Denis Johnson.

Lena: How does it feel to be back on stage?

Hari: It’s scary and exciting. I forgot how it feels to stay in character for continuous hours. It’s deep work. I think this play, in particular, is intense.

Lena: Is [the role] something that you’ve gotten to touch before?

Hari: Not really. It’s somebody at the intersection of so many different kinds of tragedies that I often lose track of them [laughs].

Lena: The Denis Johnson special!

Hari: I play a character who can’t go where she wants to go. Can’t do what she wants to do. Can’t be what she wants to be. But she’s awake.

Lena: When we first met, you had just entered the world of film and television, and you were coming out of being sort of, like, the theater queen of college. And now, you find yourself back on-stage. You’re the person I know who’s most deeply involved in this idea of, like, What does it mean to be an actress? What is this job? What does it require?

Hari: I used to think that I had to turn myself inside out in order to do a good job as an actor, or that I had to throw myself into engendering close friendships with every single person I worked with. I used to think that my soul was being surrendered up for judgment with every role that I played. And now, it’s something that I do so often that I can’t be proprietary or precious about it. I show up—prepared as I can be—and I do my job. Then I go home and live my life and hang out with the people I choose to be around.

Acting is something that I love to do; it’s not me, and it’s not my thing. The people I’m playing aren’t me, either. I feel healthier about work [these days], because I put it second.

Lena: When you and I talked about this, you gave me a speech that completely blasted my mind open. You became my self-help guru. I was like, Oh, we don’t have to become convinced that our productivity within this profession defines the entirety of who we are. There’s a special alchemy that [needs to] happen, because of the fact that actors are often at the behest of other people.

Hari: I’m really conscious of the kind of person people want to work with. If you’re coming to the table as a woman, or anything else, people want to know that they can trust you. People want to know that you’re going to keep their secrets. People want to know that you’re a good little soldier of God, for better or for worse. It’s so much easier for me to be that if I’m kind of detached from outcomes, and the whims of this industry. I can’t control how I’m cast. I can’t control how I’m seen. I can’t control how my performances are perceived. You can’t make yourself less passionate about what you do, but you can find other things to care about.

“In every aspect of our business, if the result is great, people will forget about what it took to get there. But if the result is subpar, they certainly will not.”

Lena: You’ve always had an amazing ability to zero in on the truth of what you’re doing. I was filming you for a day, basically saying, ‘Hari, can you smile?’ ‘Hari, can you cry?’ It’s the most rudimentary kind of instruction you can give to an actor. You were literally able to turn it on, and deliver a three-minute take of that exact, incisive emotion. There was no, ‘Hey, guys, that was really hard for me.’ I remember you finished crying and asked, ‘Did anyone see my avocado sandwich?’

Hari: Wait—okay, I don’t need you to name names. But do people do that?

Lena: Yes. Actors will be like, That really took a lot out of me. That really brought up a lot. They have to go into a corner and continue to let it out. And listen, here’s the thing I’ve realized: In every aspect of our business, if the result is great, people will forget about what it took to get there. But if the result is subpar, they certainly will not.

Hari: If that’s me, I won’t forget. The neurosis will accumulate.

Lena: I’ve dealt with actors whose on-ramp process is so laborious, it could almost not be considered acting, because of how much you’re having to feed the machine. I always note that when I work with English actors—because they have so much training—they come into it with a lot less intensity than American actors. You work in a much more English way. I wonder if that’s because you’re a little Shakespearean smarty who’s thinking in theory.

If you’re going into a scene, and you’ve got a lot of emotion to give, are you using a process that you learned in class? Is it a special proprietary blend of Hari emotions? How do you go in—without giving us all the secrets to your sauce?

Hari: I frequently find that the text will take me wherever it needs to take me. Just saying a word or a sentence—the process of getting it out of my mouth allows me to actually metabolize it. When I was shooting that horror movie with Stewart Thorndike, I would have to enter scenes already running and crying. We [would get] started, like, Hari, you have a two-minute dungeon warning. I would have to go away somewhere—

Lena: Into your dungeon.

Hari: Yeah, into my dungeon for two minutes. I would have to close my eyes and find where the compass was that day—what was resonating with me, that I could tap into. Sometimes, you have to cycle through your little binder of traumas. But as soon as you sync up with that, you have to let it go. And frankly, that is a last resort. If I’m present and listening and moving—and saying what I’m saying without thinking too much—something will happen.

Lena: You don’t necessarily have to think about when your goldfish died in third grade.

Hari: If there’s some kind of climactic thing that needs to happen, it’s possible that I’m going to show something specific to the character—not just the way that I would cry, or the way that I would scream.

“I feel liberated by the idea that I’m just this paper doll in the center of [it all], and there’s an army of people behind the camera, waiting to process the footage.”

Lena: I wonder what you think about the politics of being a female actor—where we’re taking some of the power from this structure that hasn’t always belonged to us.

Hari: What I like about the screen is how small a part of it the actors are. I feel liberated by the idea that I’m just this paper doll in the center of [it all], and there’s an army of people behind the camera, waiting to process the footage.

I try to go into those environments with a sense of humility and smallness—the latter not really being a fashionable thing for a woman to go into a workplace with. I find it difficult to reconcile the creative aspect of what we do with the fact that we function within the context of an industry. It’s humiliating and silly to remind yourself that you are a laborer, when you are doing these physical and mental gymnastics. In a comedy, doing a pratfall, or in a drama, with snot running down your nose, it’s quite jarring to remind yourself that you are in a union, and that you are on the clock. That you’re getting paid either an exorbitant amount, or a pittance to wring your little towel out on the floor. If you think about it too much, it gets really weird. So I try not to.

Without belaboring the point, I walk into these environments and there’s eyes on me. I’m usually the only person of my kind in a room with a hundred-plus people in it. A friend of mine—who’s had a lot of experience with negative press and positive press, high-highs and low-lows—gave me advice point-blank. She said, ‘You need to align yourself with a straight, white, heterosexual, powerful man in Hollywood. Because you are at the precipice, but those people don’t trust you yet. The way to stick this landing is to show them that you can be trusted, because you’re walking into these spaces, and they’re going to think you’re a social justice warrior. They’re going to think that the second they slip up, you’re gonna get on Twitter.’ That’s the assumption that people bring, even just with women, because of that shift in power dynamics.

Lena: The amount of times I’ve had older male actors apologize to me, because they’ve said something they think is vaguely out of touch. And I’m like, I was giggling.

Hari: Exactly. I deal with things where people misspeak, and then feel weird about it. They’re apologizing and getting all nervous, and I’m like, I don’t care about this shit. I don’t want it to be happening around me—but I’d like for all of us to just tighten up and move on. The only feelings that are relevant here are the character’s.

I just turned 30. I know who my people are. People who I love, who I built my life with—who I have friendships and sex and relationships with… There are probably a couple thousand people in this world I will ever feel that way about. So it’s kind of like, Yeah, whatever.

If you think about it too much, it starts feeling gross. You start thinking about money, and capitalism, and misogyny, and queerphobia, and transphobia. That’s why I get a little testy with my mom sometimes, when she’s like, ‘Is it so fun? Is it so exciting? Is it so cool? Are you having the best time?’ It’s like, no. Like, yes—I’m so excited to be doing the biggest job of my life. It’s amazing. But it is a job. I am not here for fun. I am here because I don’t know what else to do [laughs].

Lena: I remember my brother being like, ‘Is it so exciting to see a big picture of yourself on Sunset Boulevard?’ And this is probably the cuntiest I’ve ever been—I went, ‘It’s not exciting. And when you tell me that it’s exciting, it makes me feel like you don’t even know me!’

Hari: I mean, that’s so bratty and rotten of you to say. But it’s also true [laughs].

I’m more interested in what you have to say about this stuff—as an A-lister—than in what I have to say, as a C-minus-lister. I think it’s helpful to think about those kinds of things as not you: It’s the girl who bears your name and likeness; it’s an amalgamation of what somebody can find out about you on Google; the things that they can stream from their smart TV. Not you, but she looks like you and talks like you.

“Y’all really don’t know me. Feast on the avatar, feast on HN, feast on that thing on Google, feast on the Instagram. I’ve provided all of that for you. Whatever.”

Lena: What’s interesting about you is that you could write an exegesis on capitalism, misogyny, queerphobia—you could write the best one of anyone, one that had all the smart words, and all the smart thoughts. But you’re like, ‘I don’t need to right now, because my job is something different.’ And let’s be real, you’re the only actress I know who also writes for Artforum. It’s my favorite niche. It’s very ’70s.

When I met you, you were just getting out of school, starting to act on a professional basis. And then the fashion world was like, We see her, we want her, and we’re taking her. I wonder how you feel about dabbling in that world.

Hari: I genuinely loved it. It’s, like, a fandom that I’m part of—fashion is my Marvel. It’s my sports. It’s the thing that I talk about to people at parties. That fantasy doesn’t really grow old, when it was something I wanted for so long. I’ve connected with so many people on the internet, on LiveJournal and Tumblr—

Lena: I always forget about your life as a LiveJournal-Tumblr queen.

Hari: A lot of the people I was friends with on fashion LiveJournal—when I was, like, 14—are still in my life today. And a lot of them work in the industry now. It just goes to show how far obsession and geekiness can take you, and how there’s really no substitute for those things. Fashion is my day job, while I continue to do off-Broadway shows and independent films.

Lena: Which are your night school.

Hari: Yeah, those are my night school.

I feel like—because of how long I studied fashion—I found a way to move through this industry and burrow into a little corner of it. That being said, my time spent in front of the camera has given me an awareness of my body, of light, of what works and what doesn’t. I’ve been able to bring that to film. It’s not something I trained in—I learned it completely on the job. [Fashion] isn’t a game to me. I really like to be around this stuff, and I really like clothes. It’s more of an amusement.

Lena: I emailed you, like, ‘This fashion stuff looks like a real gas.’ And you wrote me back with your incredible take on arriving in Paris, and [being] on all the lists. We all have that fantasy—that someone’s gonna look at us and go, ‘Oh, you belong here.’

Hari: I don’t care where somebody who doesn’t know me thinks I belong. Like, y’all really don’t know me. Feast on the avatar, feast on HN, feast on that thing on Google, feast on the Instagram. I’ve provided all of that for you. Whatever.

Lena: Now that you’re working nonstop—booked and busy—how has your relationship to the Instagram changed? How has your relationship to the Twitter changed? How has your relationship to the online avatar of Hari changed?

Hari: I have a private Instagram. Frankly, I’m about to make a private Twitter, with all these weird changes on the website. I am always going to be a Welcome to my diary ass bitch. I like sharing my shit online; it’s a part of who I am. But I feel like I found a way to do it where I am somehow oversharing, while also not sharing anything at all. It’s very Libra. It’s very much, That bitch just talked about herself for 30 minutes, and I don’t know anything about her. That’s what my blue-check accounts kind of give. I think.

“In a comedy, doing a pratfall, or in a drama, with snot running down your nose, it’s quite jarring to remind yourself that you are in a union, and that you are on the clock.”

Lena: I would be remiss to let you go without asking how your life as a writer is fitting into all of this. I know that you’re a better screenwriter than most of these bitches out there.

Hari: Drag me. I haven’t written a word this whole year. This shit takes everything I’ve got. I shot two movies, a pilot, a series. I vacationed for most of July, all of August. And then I did Fashion Month, and went straight into this rehearsal process. Travel is over. The party is over. I’m not going out for, like, a month, really. And I just went through a breakup.

Lena: You have historically done your best writing in times of heartbreak. You need to get on [that wavelength] you’re on with your acting, where you’re like, I show up, I have the feelings, and I don’t need to tackle any of my own.

Hari: Well, this is my thing about writing: Am I a naturally more gifted writer than I am an actor or model or anything else? Probably. Do I enjoy the writing process? Like, not really. Is it super lonely? Yes. Do I like that? No. I think the pleasure I get out of acting comes from the social aspect of it—the fact that it’s a party, the fact that other people are what bring me out of myself. That is the magic of it for me. And so, I have prioritized it.

I haven’t found that sweet spot with the writing process. Writing is grueling. It sucks. Obviously, when you write that fab thing, when you file, that feels really good.

But I haven’t been able to take anywhere near as much pleasure in it as I do with the busy, ephemeral communion of acting. More writing will come. I think that I’m going to ride this moment I’m in now to the end. I’m not done.

Lena: Well, you put your brain into something worth reading, so I will channel it for the both of us: our 1970s-inspired secret project. We will finally show the world what we can do, when our brains join together.

Hari: I’m so excited.

Lena: I have updates for you, offline. But let the people know that we’ll finally get the Dennis Hopper, LA Hari we’ve all been waiting for.

Hari: My only goal in 2023 is to play a lead role—because I haven’t yet, and I’m ready.

Lena: Oh, I know you are. That’s why you have to hustle to rehearsal.

Hari: Oh my God. Yes, I absolutely do.

Hair Orlando Pita at Home Agency. Make-up Francelle Daly at Home Agency. Manicure Megumi Yamamoto at Susan Price. Photo Assistants Nick Brinley, Shri Parameshwaran, Tony Jarum. Digital Technician Tadaaki Shibuya. Stylist Assistant Marley Cohen. Production Gracey Connelly at Craig McDean Studio. Production Director Madeleine Kiersztan.