In their exhibition ‘Images on which to build,’ the curator provides a glimpse at underground archival imagery from the 1970s-1990s

In today’s image-saturated society, the power of photography—its ability to capture culture and history—often slips through the cracks. The latest exhibition from writer, curator, and photographer Ariel Goldberg is a long-awaited necessity, breaking through the normative Eurocentrism standard of art history. Their show, Images on which to build, “presents the processes of trans and queer image cultures that created spaces beyond the visual, where experiences of affirmation, recognition, and connection formed legacies that shape our present and future.”

In their presentation for the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial, Goldberg showcases various art forms from a queer, feminist lens. But rather than being relegated to a venue explicitly centered on queer or feminist art, Images is on display at Cincinatti’s Contemporary Arts Center—an indication of a broader institutional change. It’s exhilarating to see the archives together, and heartbreaking to see the extent of what was missing from them.

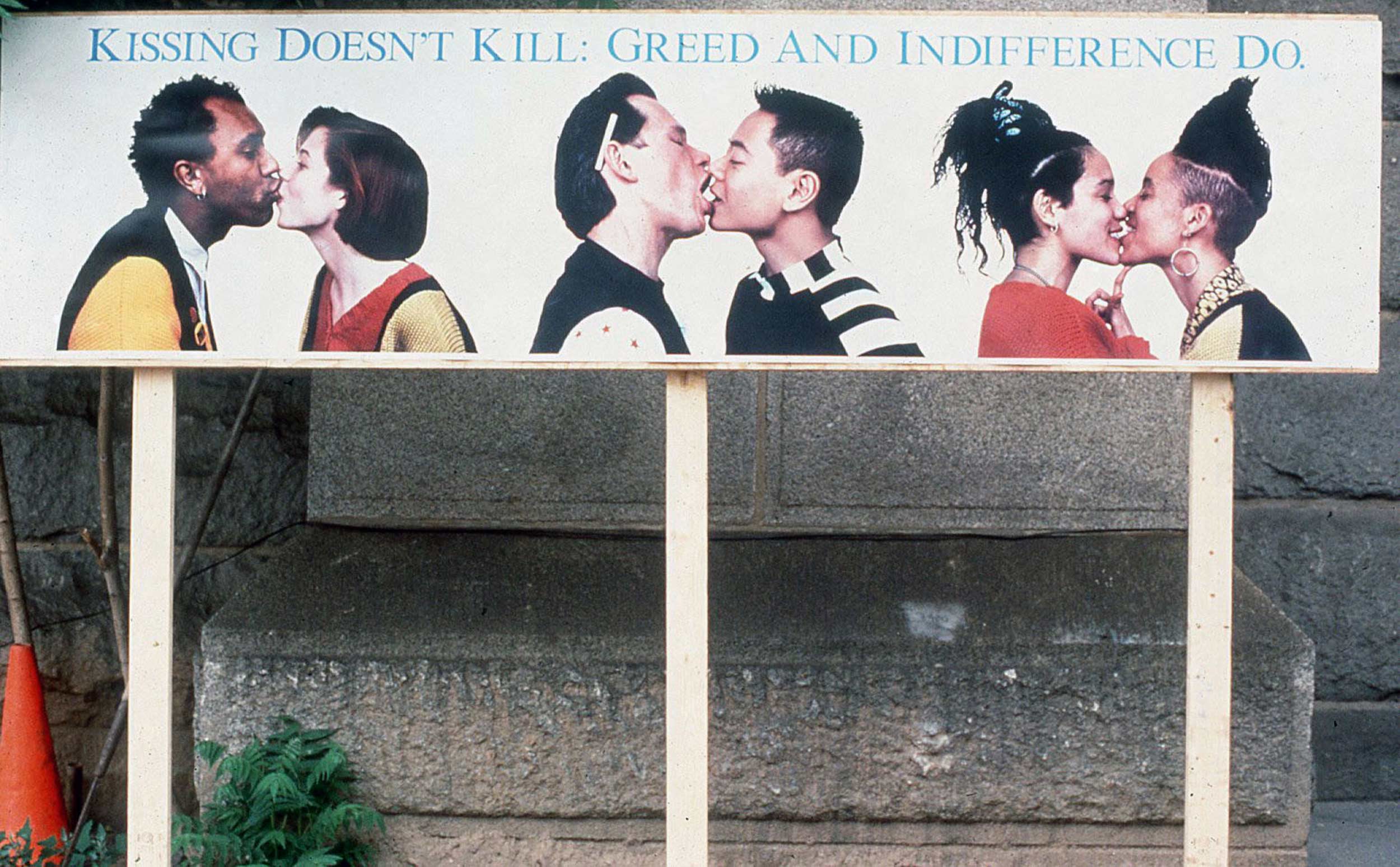

Goldberg organizes Images into six sections: Joan E. Biren’s (JEB) The Dyke Show, Lola Flash’s In and Alongside ART+ Positive, Diana Solís’s Intimacies in Resistance, Lesbian Herstory Archives’s Keepin’ On: Images of African American Lesbians, Electric Blanket’s AIDs Projection Project, and Little Gem’s Trans Image Network. Magazines, portraits, newsletters, snapshots, and poetry introduce a small fragment of the liberation movement from the ’70s to the ’90s: three decades once nearly lost from collective memory. The exhibition captures the bliss of queer people when they’re living freely, and the agony when they’re desperately calling for community—or when the small one they have is dying.

The curator led a conversation between JEB, Flash, Solís, and Shawn(ta) Smith Cruz, a co-coordinator of the Lesbian Herstory Archives. Afterward, I ran into JEB; she was sitting in the gallery observing everyone who passed through. She was still getting used to people watching The Dyke Show, as before, it was only advertised to women. Now, it’s open to a new public—one filled with cishet men. JEB wasn’t even sure if they knew what they were watching, amazed at how long they stood in front of the screen. I asked, “Why did it take this long?” She responded, “It’s not why—because I know why. It’s a miracle that it happened.”

Madison Bulnes: When did you first get interested in the practice of uncovering history and bringing it into the public?

Ariel Goldberg: I felt like my life depended on finding out what was absent in trans and queer photographic activity. I knew there had to be more out there than what was easily accessible, and there is! I have encountered, in my research, an infinitude of people creating all different types of work.

I don’t think I’m finding anything; I’m trying to decolonize my logic around it. A lot of people have done amazing work, and it’s under-recognized. It’s more about listening, reading, and joining the artists, educators, and activists who have been on the steady liberation project work in different forms. If people in my generation are not talking to the people in older generations, valuable, beautiful, embodied, powerful, and transformative knowledge is going to be forgotten. In preparing the exhibition, I realized I wanted to create an experience for people to be, like, Whoa, there was so much. We’re told there’s so little for this period—just Robert Mapplethorpe or Catherine Opie—but there were dozens of other works that never rose into the so-called art discourse.

Madison: Were you trying to find your own history?

Ariel: Absolutely. I was finding trails, like little seeds. I read a piece by curator Sophie Hackett in Aperture which was about JEB’s The Dyke Show. From there, I looked JEB up. Smith [College] acquired her papers, and I spent six weeks at the Sophia Smith Collection, researching Diana Davies, lesbian periodicals, and visiting the Sexual Minorities Archives. JEB was at the hub of a lot of literary, film, and music cultural activity in the 1970s, because she was a part of two different lesbian collectives; Moonforce Media and The Furies. JEB’s papers opened me up to names. Once I found a person, I became inundated with more. I still can’t keep up. I have lists of archivists, photographers, and activists who I want to have conversations with.

Madison: Why did you choose to focus on the work of JEB, Lola, and Diana, alongside the other archives?

Ariel: JEB, Lola, Diana, and Shawn(ta) of Lesbian Herstory Archives, were the people who were able to come out for the FotoFocus Symposium, and that conversation is the bedrock to the show. They’re all queer women, or gender non-conforming individuals. I’m also centering Black and Brown women; JEB is white, but has a strong anti-racist ethos in her image-making practice. I wanted to honor Diana’s, Lola’s, and JEB’s work together. One of my goals is to zoom out and look at image cultures occuring across the US in the 1970s-1990s. The six projects in Images are shows within a show. With JEB, Diana, and Lola, in particular, I wanted to look at different geographies. JEB was based out of DC but traveled with The Dyke Show. Lola’s work is in New York and London. Diana’s work reflects her worlds in Chicago and Mexico City; she has been defying state borders her whole life.

Madison: Would you consider this show a form of representation or education?

Ariel: The show can be anything and everything. People will have their experiences, and I welcome whatever ways people process this material. I don’t think it’s either representation or education; I want to move people. Personally, I’m less excited about the concept of representation, because I find it does not go far enough to enact structural change. I tend to look for, and question, all that is not visible in photography—but I also delight at what is made visible. The unifying factor of all these projects is that now they’re educational, and they were intended to be educational at the time they were made. What I’m trying to capture in the energy of the work is that people are erased.

I like to think of the images in the exhibition as documenting vibrant places. The images are our vehicle for time travel. I’m interested in how people were learning and growing. Cameras were present, and cameras participated in educational projects, but I think a protest could be an educational project, too.

A passerby sees a sign that says: ‘Keep cops out of gay bars,’ like the one in one of Diana [Solí’s] photo, and they start to think differently. Lola [Flash’s] work is about sex positivity and doing the opposite of what the Christian-right did during the early days of the HIV/AIDS crisis. It was, like, ‘Oh, you’re scared of nudity? Well, we’re a group of friends, and we’re going to take nude pictures of each other because our friends are dying, and we’re trying to live.’ Those are the records that we’re left with to learn from. I like to think of it as a circular loop.

Madison: How do you think queer and trans photography has changed since the time period of the exhibition?

Ariel: Everything’s always changing, but things are also moving slow. It’s a bit of a push and pull. JEB likes to think of photography as a triangle, where the photographer, subject—what she calls the muse—and audience are at the three points. The thing that has changed most dramatically, in terms of that triangle of interaction, is the audience. The cameras in people’s hands today have dramatically increased. Now, the audience are also the photographers.

Being a photographer in trans and queer spaces used to require a very specialized skill. Not everyone had the equipment or training to make pictures. People were either building their own darkrooms to make images because they couldn’t drop them off at photo labs; or they were taking the risk [when they did]. In the late 20th-century, the average trans person maybe had a point and shoot camera and did awkward self-portraits or had their friends take pictures. Now we’re inundated. A trans person can take a selfie of themselves five times a day and send it to their friends or post it on social media. When trans people were writing letters to each other in the ’80s, a line that kept being repeated was that they ‘felt like the only one.’ They were totally isolated and out of sheer survival, building support groups to escape that feeling. Today, more people have resources to build communities.

Images on which to build, 1970s-1990s is on display at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center until February 12, as part of FotoFocus 22: Biennial: World Record. On March 10, Images will move to Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, where they will be on display until June 30th.