Directors Will Lovelace and Dylan Southern discuss their gritty tribute to New York’s indie scene, featuring archival images from Hedi Slimane

Remember 2001? There were sexy American Apparel ads in subway stations, flash photographs in basement parties, and softbois in Williamsburg cafes. It was the age of smudged eyeliner and skinny ties; the moment of heroic chic and hipsters. Everyone wanted to be Julian Casablancas, or fuck him, or, more likely, both.

Even if you cringe at all these past memories, there’s no denying that those indie sleaze years were a cultural milestone. The same is true of the post-punk revival that accompanied it: We were gifted The Strokes, The Rapture, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol, and LCD Soundsystem, all etching an enduring scene in our brains forever.

In 2017, Lizzy Goodman, who was there sweating in packed Brooklyn venues, told the era’s story better than anyone else. Her book Meet Me In the Bathroom captured the new sound taking over Brooklyn in the early aughts. Goodman held about 200 interviews with participating musicians, journalists, bloggers, photographers, managers, groupies, and DJs—just about anyone and everyone living in the scene. Her five years of research, conversations, and writing became the New Testament, following Gillian McCain and Leg McNeil’s Please Kill Me.

Now—thanks to directors Will Lovelace and Dylan Southern—there’s a nostalgic time capsule that will satisfy visual learners and diehard fans alike. Their documentary illustrates the rise and fall of the scene, starting with The Moldy Peaches playing at SideWalk Cafe’s open mic nights in the East Village, and ending with a revamped Brooklyn waterfront, jeopardizing unstable rock stars’ lifestyles with rising rents. It’s a naïve analysis of those last years, perfectly mirroring the wide-eyed dreams that kicked off the beginning. It must be noted, however, that in reality, those bands were gentrification’s original catalyst.

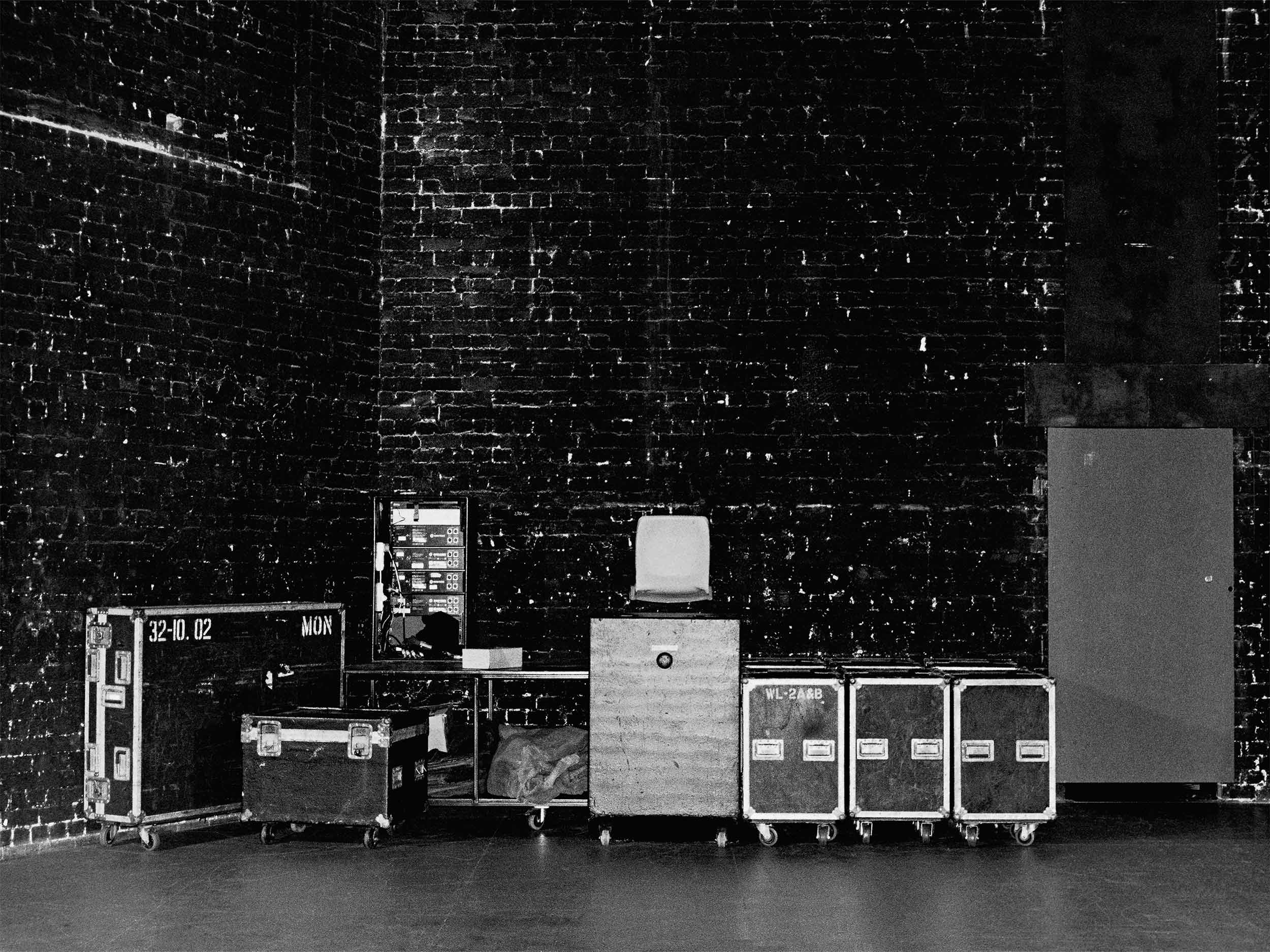

Still, Lovelace and Southern’s Meet Me In the Bathroom documentary is earnest and intoxicating. Never-before-seen archival footage transports us to those glorified grungey days. The days when artistic endeavors could successfully be fulfilled. The days when New York City was the place to be.

The two directors take us on the journeys of Paul Banks, Casablancas, Albert Hammond Jr., Kimya Dawson, Alex Green, James Murphy, and Karen O, through deep-cut, low-res videos. Vignettes of each band overlap, as the film jumps from story to story. The struggles behind their idealized, hedonistic lives are on full display through footage from early shows, studio sessions, and tour diaries.

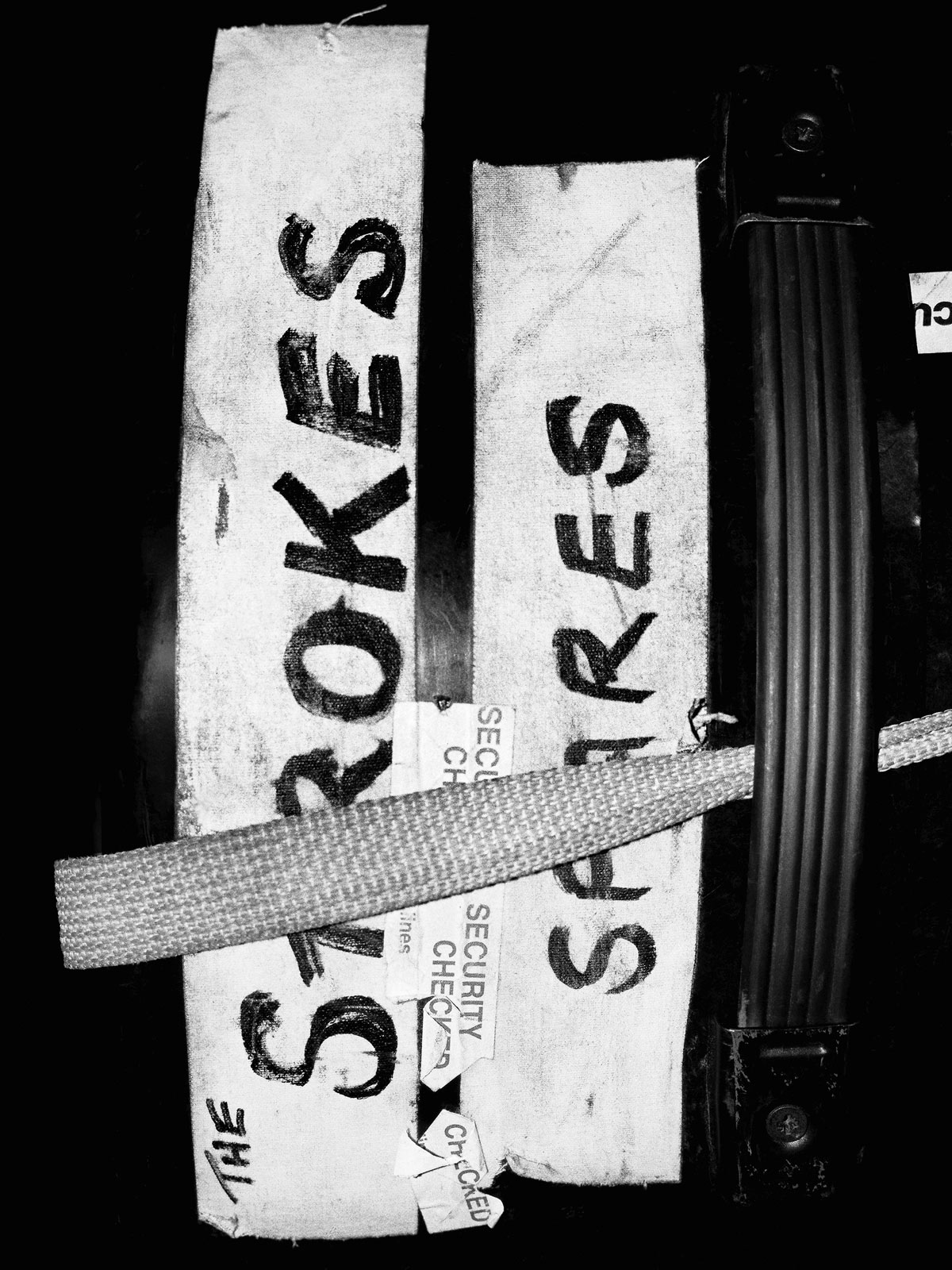

In many of the scenes, bands perform wearing destroyed Converse and blazers thrown over t-shirts. It’s part of the boyish charm. Karen O’s eccentric, punk-rock stage costumes are even more enticing and badass. Style was subconsciously a vital part of this era, and Hedi Slimane was the pioneer. At the time, he was the creative director at Dior Homme, dressing The Strokes and photographing their shows. He’s the one who made skinny silhouettes rockstar chic, whispering underground punk into haute couture. Now the creative director of Celine, Slimane remains among today’s most recognized photographers, having captured subculture at its peak through his online diary. He recently delved into the archive, sourcing images to create limited edition Meet Me In the Bathroom promotional posters for the film’s release at the Fonda Theatre (October 27th) and Webster Hall (October 30th).

Ahead of the film’s premiere, Document spoke with the directorial duo about their narrative techniques, and the impact of a movement happening across the pond.

Madison Bulnes: When did you first come across Lizzy Goodman’s Meet Me in the Bathroom? What were your initial reactions?

Will Lovelace: We were very fortunate to read the galleys of the book ahead of its UK publication. The scene was happening when Will and I lived in Liverpool. I remember thinking, ‘I’ll have a quick scan,’ then finding out three hours had passed when I looked at the time on my laptop. It was such compelling, compulsive reading.

Dylan Southern: I love the format of oral history. Not only does it chime with the way we consume media now—in short bursts, making it such a binge-able literary form—but the Rashomon quality of events, recounted from different perspectives, and the truth being somewhere in the midst of it all, is really addictive. More than that, it evoked a different world. It was sobering, in a way, realizing how much time had passed and how much the world had changed.

Madison: When did you realize you wanted to bring her book into a visual documentary?

Will: Having made music documentaries in the past, we’d all decided not to make another one—but there was a specificity to this time and place that we were drawn to. It felt like we could make a different kind of film than the previous ones [we’ve made]; a film that situated the audience in that particular time and place.

Dylan: Initially, we pitched it as a four-part documentary to all the streamers. There was a lot of interest, but ultimately, it didn’t pan out. There was probably some algorithmic assessment of whether the scene was big enough to warrant the budget we were asking for, and the computer said, ‘No!’ So we reassessed, knowing we were biting off a lot, and looked at ways we could use the book as inspiration for a feature documentary.

Madison: What role did The Strokes, Interpol, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, LCD Soundsystem, and other such bands play in your own life?

Will: It was a scene that emerged just as Dylan and I had graduated college; it soundtracked our lives at that time. We were based in Liverpool, and starting out as filmmakers—which is a way too lofty way to describe what we were actually doing. We bought a camera with a European grant, and were making music videos for local bands, and corporate videos for local businesses. Our day-to-day could be quite unglamorous, but that music brought another world to our office on Rodney Street!

Dylan: In our teens, we’d watched guitar music take a turn into a weird nationalistic, nostalgic parody. By our early 20s, when you looked at what was popular, it felt like nothing was happening. There was interesting stuff in other genres, but the music press—particularly in the UK—loves a movement it can put a label on, and there was nothing like that to get behind for a few years.

Those bands filled a cultural gap. The UK music press, which at that time still had some heft, got behind them first. It often felt like this explosion of New York music was happening here in the UK. Maybe it was the exoticism of New York, after years of flag-shagging Britpop, but for the first time in a few years, it felt like there was a cultural groundswell.

“So our approach was that the film had to act as a time capsule; it had to lean into what an archival film can do best—bring an era to life in an evocative and visceral way.”

Madison: The documentary takes place over five years. How did you decide which events you wanted to cover?

Dylan: It was tough and really daunting. Taking a 600-plus page book and using it as the inspiration for a 90 to 100 minute film is an insane task. Making that film for music fans, who are understandably passionate, knowledgeable, and opinionated on the subject, adds to the anxiety! What’s so great about the book is that it’s so exhaustive—so granular—and able to explore every facet, intersection, and detail of the scene in a way that a film never could.

We were always of the mindset that, if the book existed, the film could ignite that interest in new audiences, inspiring them to pick the book up and dive in deeper. So our approach was that the film had to act as a time capsule; it had to lean into what an archival film can do best—bring an era to life in an evocative and visceral way. We didn’t want to make a film that had cultural commentators popping up to contextualize the time—we just wanted to present it.

Will: In terms of deciding who to include and who to omit, those decisions were made both in pre-production and in the edit. When approaching a documentary, in the writing stage, we find it useful to look at analogous fiction genres to help guide the process. With this film, it was ‘coming of age’—that’s why we opened with Karen O talking about Dirty Dancing. Our initial approach was to see which of the characters had the most striking coming-of-age stories, giving us the architecture to build our archival story around. Arriving at four key artists, we then looked at how their stories intersected, and what bands and artists could become satellite characters. It meant that bands and characters we would have loved to include sometimes fell by the wayside—but those are the choices you have to make. Our earliest edit was over four hours long, and at that point, we were worried we’d never be able to get it to length!

Madison: How does the Y2K scare and 9/11 attack frame this scene?

Dylan: Y2K was a crazy moment of technological anxiety; a false alarm that seems quaint or semi-ridiculous in hindsight. Through the prism of today, when technology has changed the world so irrevocably, that fear and paranoia seem entirely warranted—if misdirected. In the film, it’s a timestamp. It’s kind of funny, but it’s also a harbinger of the impact technology will have on the world in just a few short years.

The 9/11 attack was something that had to be included in a film about New York at this time, but we knew we had to be sensitive about its inclusion. The world’s eyes were on a city in existential shock. None of the artists in the film were overtly political, but what was so interesting about the section on 9/11 in Goodman’s book, was that it dealt specifically with the impact of that event creatively. We’ve seen the political and societal ramifications of 9/11 play out over the last 21 years, but Goodman’s book was the first time I’d read about the impact on New York’s artistic community; it was in that spirit that we approached it in the film.

Madison: What struggles, if any, did you encounter in telling a New York-specific story from your UK point of view?

Will: Before Covid hit, we planned to relocate to New York to make the film, but that plan had to be revised for obvious reasons. Because of the lockdown, the film went from being 60 to 70 percent archival content, to being a hundred percent archival.

In other ways, COVID also helped, because the people we had doggedly hunted down through 21-year-old message boards and photographic clues—there was a lot of detective work involved—had time to go into their attics and find dusty old DV tapes.

Dylan: I don’t think having a UK perspective made us encounter any struggles we wouldn’t have had if we were American directors—not for the type of film we set out to make, which is constructed from material that originates from the time. It also allowed us to look at it as objective filmmakers, rather than subjective participants.

Madison: Multiple bands are shown during early tours in England. Were you there for any of those?

Will: Not the early tours, but certainly subsequent ones. I remember friends going to see The Strokes on that first UK tour, and being jealous they got tickets.

Madison: Before COVID occurred, you both were planning on shooting original footage in New York. What were you intending to film?

Dylan: A lot of the stuff we planned to shoot was cosmetic: particular sequences that would be used to chapter or frame the narrative. There was initially a plan to shoot an ending sequence that brought us back to present-day New York, focusing on how significantly the city, and the world, had changed.

Madison: How do you think new footage would have changed the film?

Will: I actually think the shift to a hundred percent archive was to the benefit of the film. It allowed us to remain in the moment. The New York material might have made it less raw and messy, but given the subject matter, it feels like that would have been a loss.

Madison: What does bookending the documentary with Walt Whitman’s poem add to the story?

Dylan: It was our way of taking a somewhat tongue-in-cheek look at the way mythology is created around music. The poem itself, and the reading, approaches New York with a kind of overwrought romanticism.

As a framing device for the story, the idea was that it initially introduced the idea of New York as a beacon to artists—a place with a highly romanticized cultural and musical history draws a certain type of person, with a certain notion of what the city represents. The bands in the film were certainly influenced by that heritage. You can’t listen to The Strokes without hearing the influence of the Velvet Underground or Blondie; you can’t look at the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’s presentation without thinking of Warhol. Similarly, DFA [Records] and LCD [Soundsystem] are, in part, a composite of their influences.

The reprise of the poem and cutting style at the end of the film—in which the images of the past were replaced by the artists whose stories we’d just seen unfold—was included partly for symmetry, but also to raise a question of whether they had earned a place in that canon. Or if that’s even possible today. Ultimately, that’s for the audience to decide.

Madison: Where is the ‘New Brooklyn’—the city that allowed this groundbreaking music scene to start?

Will: The internet.

Meet Me in the Bathroom will be released in theaters on November 4 at New York’s IFC Center, and Los Angeles’s Los Feliz 3 Theatre. A national theater opening will occur the week of November 11.