In Todd Field's psychological drama, the artificiality of traditional musical scores is confronted with the reality of everyday life

When I—and assumedly most people—sit down to watch a film, my primary focus rests on the dynamic images moving on screen. I do my best to follow the dialogue, an integral part of the diegetic sound, as I understand a film by means of listening and watching. There are many channels of information which come together to create a film, but the one that seems to routinely occupy an “unnatural” space is the score.

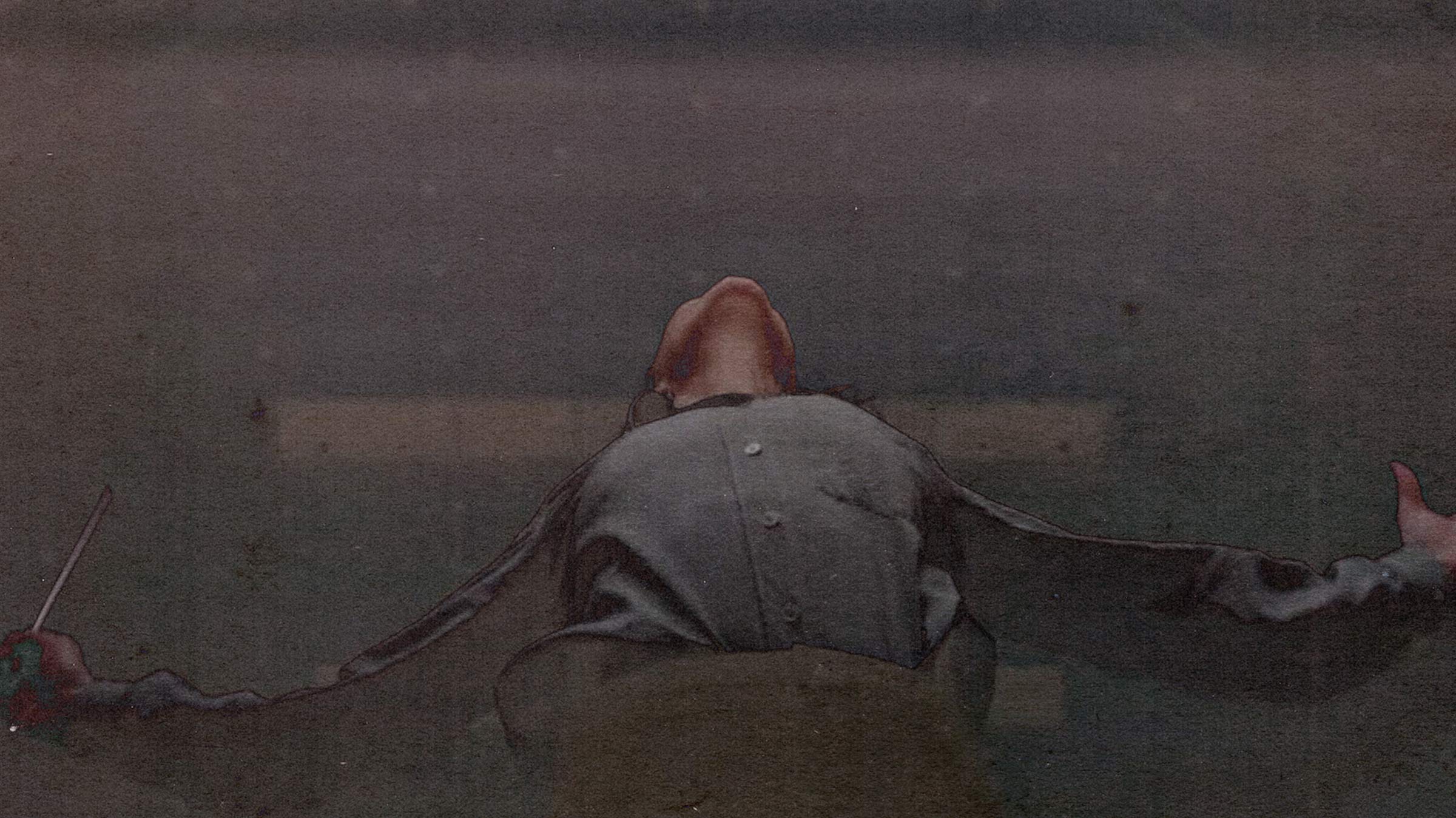

Todd Field’s psychological drama TÁR considers the artificiality of traditional musical scores against the reality of everyday life; the score does not function to help the audience locate itself in scenes that may be unusual, exotic, or far-fetched—it instead comprises the scenes themselves. The score is the storyline, as we follow a fictional character—revered composer Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett)—in the weeks leading up to her completion of the fifth Gustav Mahler adaptation, while she’s simultaneously attempting to write her own music.

Prior to watching TÁR, my comprehension of scores was fairly rudimentary; I relied on musical clichés to embody and (sometimes explicitly) explain actions and emotions on-screen, distinguish relationships among characters, interpret the narrative, and maybe even predict what was to come. I saw the score as an ephemeral additive, and the characters as an essential element. What I realized as I watched TÁR is that music is no passive device in this film. Music is Lydia’s kryptonite: It gives her power, but it also destroys her in the end; it fuels her extreme rhetoric of cunning camaraderie and subservient love interests; it acts as a pipe dream. In TÁR, nothing exists without the score—it’s the very thing the characters are chasing.

“This film gracefully subverts the wonted role of the score, giving it overdue autonomy in a medium where it’s typically designed to underline and punctuate.”

After the screening, I spoke to Hildur Guðnadóttir, the real-life composer behind the work of the fictional Lydia Tár. She articulated the process behind her mellifluous musical practice and her illusive role in TÁR—being both “invisible and incredibly present at the same time.” The only moments in which the audience thinks it hears the score, is when the characters hear it, too—but that’s not the case. This film gracefully subverts the wonted role of the score, giving it overdue autonomy in a medium where it’s typically designed to underline and punctuate. Guðnadóttir demonstrates that the power of music and film is found in their ability to negate and trust each other on screen. TÁR’s score transcends the duty of didactic hinting, instead occupying a topical and dynamic point of action. Guðnadóttir’s approach to score asks us to reconsider the preconceived notions of cinematic music, and what it means to create a movie based on listening as much—or maybe even more—than watching.

I urge you to go see TÁR when it comes out in theaters on October 7. It is a movie that floats in an era where so many films are drowned by a callous Hollywood agenda and redundant roles. TÁR is trodden by an arresting realness—New York Post headlines, austere cinematography, self-actualizing music, and a role that feels so uncannily familiar that you trick yourself into thinking that you once knew of Lydia Tár.

Razzi Schlosser: I noticed that this film incorporates a score that’s always motivated by the action of the story—and remains strictly diegetic from what I remember. Can you tell me a bit about the intentions behind that choice?

“The score is pretty much inaudible. It’s like you have a feeling of a ghost in the room—you’re probably not going to hear it, but you will feel it.”

Hildur Guðnadóttir: It’s interesting to hear you call it action. I think my job was three-fold; it wasn’t just the score itself. I was involved from the very beginning, from the [earliest] days of the script. I think I was the second person to join the project, after Cate. I had a lot of meetings with Todd in Berlin about the tempo of the characters, and we set a BPM for different characters and different scenes. We tempo-mapped the whole film. He wanted to approach the story as a musical process.

My second job was to write the music that [Cate] was writing in the film. In TÁR, you never hear the finished version of the music she is writing because, again, this film is all about the process of making music. It’s really going into the finer details of what it means to write music. Unless you’re a musician, it’s a process you’re normally not privy to. But it’s probably the aspect that I find the most fascinating.

The third job is bringing us to the realm that’s so present in the film—this kind of subconscious, otherworldly realm, the place where you’re unsure if it’s real. Because the day-to-day life of this story happens in orchestra rehearsal, it was really clear that the music couldn’t be of that world. It had to be something other than an orchestra score. It had to be otherworldly, and also in the space of almost not being there—the score is pretty much inaudible. It’s like you have a feeling of a ghost in the room—you’re probably not going to hear it, but you will feel it.

Razzi: I’m sure that the role of the sound designer was also a huge part of engineering that feeling.

Hildur: Absolutely. Because that’s what’s so fascinating with music and sound, is that you can work on such a subconscious level—this place where, if there’s a sound going on around you, even if you close your ears, you’re not going to escape it. It’s such an effective way to alter your state without you really even noticing it, because you can completely change a space with a piece of music. If you enter a room and there’s upbeat music playing, your body’s gonna react to it.

“If the film is a car, the score is the engine. The engine is the part that drives the car, but it’s not necessarily the part you’re going to see unless you make the effort to look under the hood.”

Razzi: What were your initial impressions of the screenplay and how did you react to them while writing the music?

Hildur: My initial reaction can be heard in the melody that [Lydia is] writing, because that is the thread that follows her throughout the entire film. It’s this one melody that she’s trying to figure out. [It was] the first thing that came to me musically, and it came to me almost immediately after I read the script.

And then it was a dialogue [between us]. Because this is a film about process, it was really important to Todd that the film was also a process—he didn’t want to go in and be like, This is how it is. The film had room to change a lot; it’s probably very different to what we set out to do in the first place. But that was the beauty of it.

Razzi: Were you well-acquainted with Lydia’s inspirations, like Mahler and Elgar?

Hildur: I did research the music that was being performed. But I didn’t want it to influence either the score nor the music that she’s writing, because one of the most important things about her character is the frustration that she’s experiencing from not following her musical passion. She’s not really able to stay with what she actually wants—to be writing or performing—because in her heart of hearts, she wants to be going [in] an experimental direction, in the lines of Charles Ives or Górecki. She’s kind of been pushed into this classical realm. That’s where we felt so much of her frustration lies. She’s not really bringing them together, so I didn’t want Mahler to seep into the music that she’s writing, or the score itself.

Razzi: Can you tell me about a decisive moment during the score that might go unnoticed by most audiences?

Hildur: I guess the whole score is kind of like that—not even just the score. My role is both invisible and incredibly present at the same time. But it probably won’t be very obvious to the audience—like, what my role actually is in the film. But I think Todd explained it very well. He said that if the film is a car, the score is the engine. The engine is the part that drives the car, but it’s not necessarily the part you’re going to see unless you make the effort to look under the hood.

“Music, conversation, communication, it’s all about timing. It’s not just about what you say, it’s also about how you say it and when you say it.”

Razzi: And what was it like working on this film in comparison to your past experiences? I know that you’ve worked with bands like Animal Collective, and a few in Iceland. How do these practices differ from one another?

Hildur: I think that every project and every person you work with is just incredibly different. Music is all about communication. So when you’re writing scores or playing music with someone else, in a band or in whatever setting, you’re kind of finding a way to communicate that goes beyond words. It’s a communication that peels away the need for words. And the longer you work with people, the less need you have for words, which is why I try to really nurture the musical friendships that I have.

In this conversation with Cate and Todd, the big difference is that the dialogue was so strong. Both Todd and Cate went to such great lengths, diving so deep into communication, because that’s where the process really lies, it’s in that beautiful way of speaking and listening. There was so much listening in this film, because everyone is aware of the big part listening plays in the process of making music. It’s like, What is everyone else playing, and how can I react to that? And, How are we playing together? It’s not How good am I? Or, Look how much I can practice, how fast I can play.

Razzi: Why were you compelled to be a part of this film?

Hildur: I saw that the music was very important to [Todd], because he actually used to be a musician himself. He used to play the trombone. He definitely understands music very well, and he understands what it means to practice music very well. I think a lot of projects today—a lot of films and TV—use music to underscore the entire storyline. So you have music where someone walks into the room or breaks the door or something, and you hear a Kaboom, da, da, da, da, and then you have music to go with every facial expression. For me, that really takes away the power of what music can really do. Music, conversation, communication, it’s all about timing. It’s not just about what you say, it’s also about how you say it and when you say it.