“Tending to the past, Ernaux casts out fearlessly into stormy waters and recovers what has been cloaked beneath their surface.”

Last week, the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2022 was awarded to the French writer Annie Ernaux. Per the awards body, she was selected “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.” Put otherwise by literary Twitter—and more specifically, by Ernaux’s English-language publishers at Seven Stories Press—“Parents! Make sure you check your children’s Halloween candy, it could be containing sharp objects. For example, the line: ‘I have left part of myself in a place where I shall probably never come back’ from Annie Ernaux’s book Shame.”

Born in Normandy in 1940 to a working-class family, Ernaux excelled at her strict Catholic school before finding work as an au pair in London, and then becoming a schoolteacher and scholar of literature in the 1970s. Her career as a writer gained speed in the 1980s after her first autobiography, A Man’s Place (1984), won the Renaudot Prize. This catalyzed a great career in nonfiction, as Ernaux has devoted more than a dozen volumes to the act of illuminating her own life, turning it over again and again and sketching it from various angles. As Joanna Biggs puts it, “Ernaux hasn’t written about her life in a neat this-then-that sort of way. Reading her is like getting to know a friend, the way they tell you about themselves over long conversations that sometimes take years, revealing things slowly, looping back to some parts of their life over and over, hardly mentioning others.”

Across each new book, Ernaux has chronicled encounters with trauma, love, abortion, class, education, and secret affairs with startling frankness. Rendered with her surgical precision, a crush is crushing and the past is never passed. Yet her language could never be described as florid or sentimental; she takes all of the pejorative charge out of ‘plain’ or ‘spare’ prose—indeed, to write in straightforward language and manage to preserve the subject’s profundity is the heart of her astonishing gift. Tending to the past, Ernaux casts out fearlessly into stormy waters and recovers what has been cloaked beneath their surface, but she is also not afraid to examine the holes in her net, or the fallibility and porosity of memory itself. She meets ephemerality with a hammer and nails it to the wall, enclosing its amorphous shape in grounded, nimble language.

Ernaux’s books are accessible, and with their wide variety of subjects, one can really start anywhere—but there can also be a more strategic route, if you want to glean some of the patterns or connections that really make her corpus, as a whole, sing.

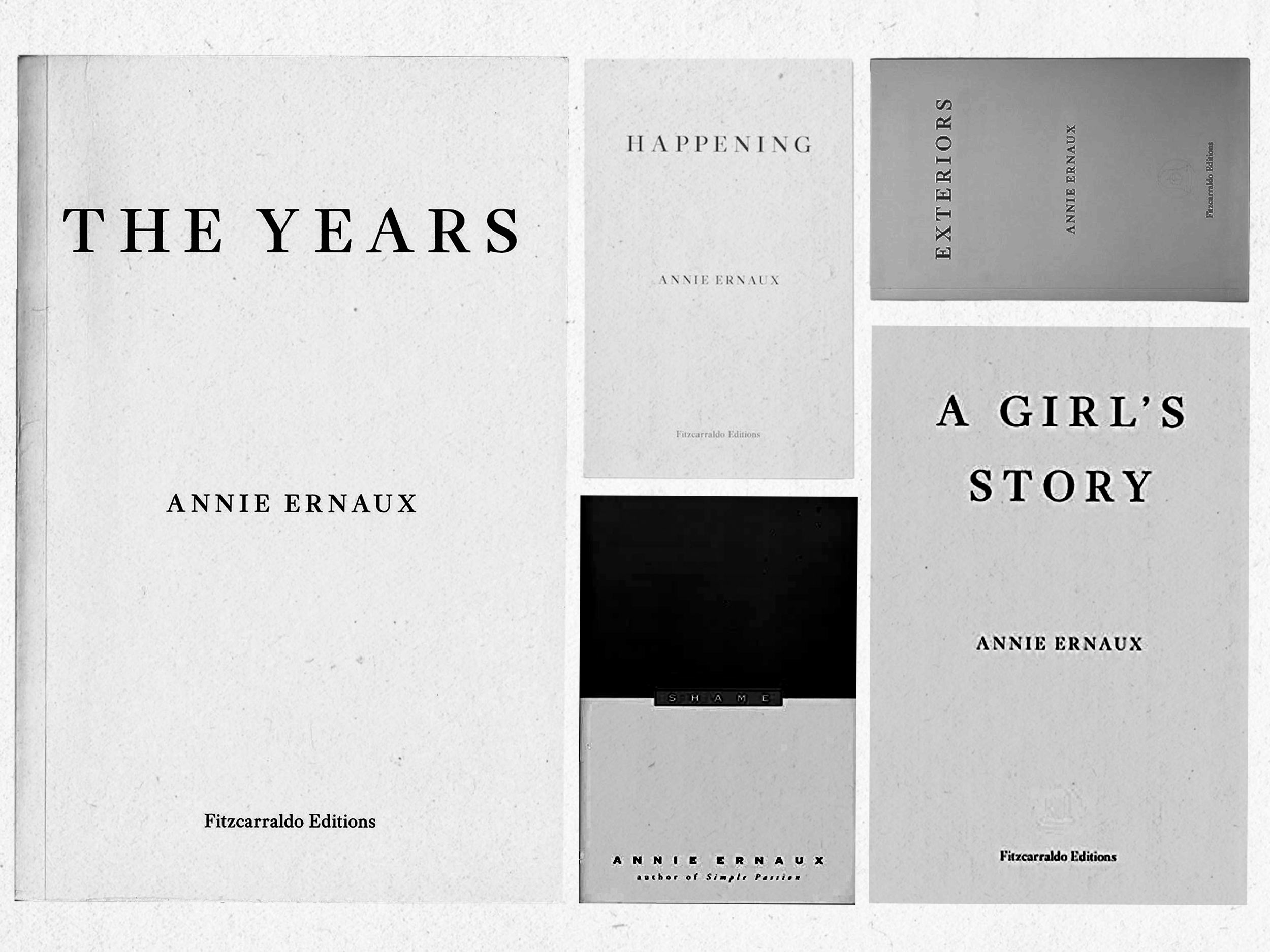

The Years

Ernaux’s most decorated—and perhaps most ambitious—book is The Years, written in 2008 and translated into English by Alison Strayer in 2018. It has been described as a “collective autobiography” in its attempt to tell the history of post-World War II France through a young woman’s life and her encounters with a rapidly-evolving culture. Ernaux writes in both the third person and the broader ‘we’ form, playfully tugging at the edges of the self and society.

This year, in a broader extension of this project, Ernaux and her son David will release the film The Super 8 Years, drawing on 8mm footage of their life in the 1970s that has been narrated by Ernaux herself. The Super 8 Years is not an adaptation, but it continues the work of sifting through—and creating—sedimentary layers of history, both personal and social.

A Girl’s Story

My own first encounter with Ernaux came from this more recent memoir—a turn to her teenage years and a traumatic sexual encounter at summer camp. In an age when many memoirists are stubbornly wrestling their trauma into a clean narrative, Ernaux steps away from ordering her pain, giving it a name, making it dance, suturing it shut, and applying a Band-Aid. For Ernaux, ‘coming-of-age’ does not bring a whole self to fruition, but rather, initiates a confrontation with the body, and the ways in which it may not survive patriarchal society. Six decades later, she returns to her 18th summer, to “the perpetually missing piece […] the unqualifiable hole,” that has dogged her ever since. Ernaux reaches into the past and opens up the gap between what she felt and what she said, dreaming “of a sentence that would contain them both, seamlessly, by way of a new syntax.”

Happening

Set in 1963, Ernaux recounts the events of her abortion, undertaken while she was a student 12 years prior to the decriminalization of abortion in France. Happening is an incredibly forthright, unsensational account of the covert efforts to secure reproductive choice in a sexually conservative, Catholic culture, but it is also a stunning portrait of a body and a will that are furiously at odds. For young Annie, the sting of pregnancy is also tinged with the “inescapable fatality of the working-class […] the thing growing inside me I saw as the stigma of social failure.” In this way, Ernaux shades in the history of abortion with the nuances of class, ultimately knitting together the story of the body with the story of the state that manages it. “People judged according to the law, they didn’t judge the law,” she writes of a pre-Veil Act France.

Happening was also the source material for Audrey Diwan’s 2021 film of the same name, which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

Shame

In the late 1990s, Ernaux returned to a moment that punctured her childhood—watching her father try, one Sunday in the early afternoon, to kill her mother. This encounter with violence becomes a lens for examining the ways in which memory works, and how, in particular, it is wont to be shaped by encounters with harm that stick, even as they may otherwise go unmentioned and unacknowledged. This story takes her down the steps into small-town French life and offers a look at its hierarchies and rituals, including those from which she has sought to break free, through writing.

Exteriors

Exteriors is not concerned with the past—at least not in the same way Ernaux’s other books are, with their sharp sense of focus, efforts at recall, and sense of being haunted. Here, Ernaux turns up her skills of observation to describe fleeting moments and characterizations of people and places on the fringes of Paris. Written as seven years of journal entries, Ernaux describes shops and cafes, trains and streets, with the same insight that she has directed towards the past, now beaming outward onto the culture around her.