Emerging from the tragedies of the pandemic, their latest album ‘SPARK’ sees the band’s strongest sonic evolution to date

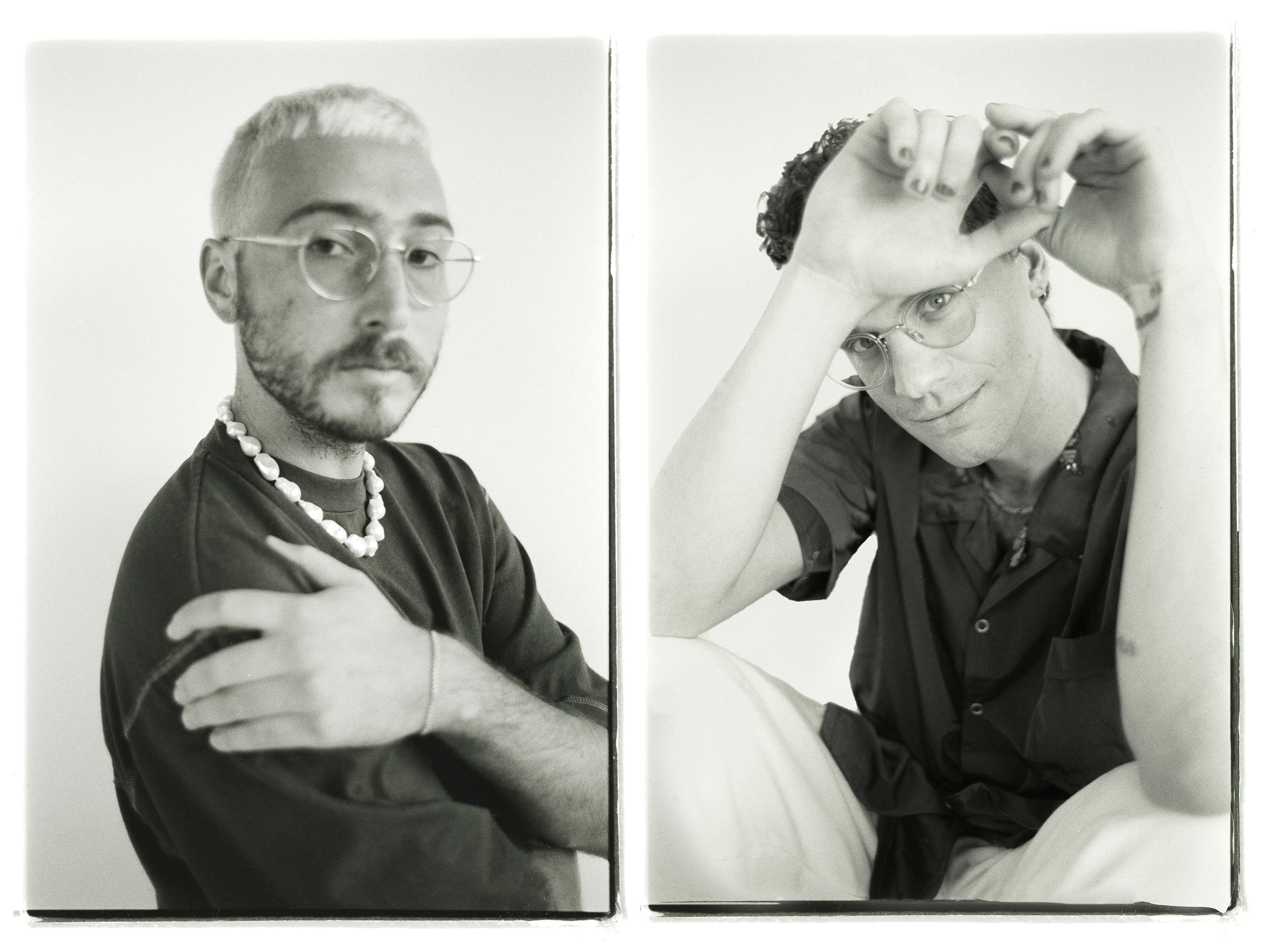

The most important thing to understand about Whitney is something you can’t fully understand unless you’re Julien Ehrlich or Max Kakacek: the strength of the band’s bond. Standing between the pair—who are both taller than you might expect—there is a palpable energy that comes from 10 years of living and working together, in what Ehrlich jokingly calls their “life partnership.”

“There’s a lot of nuance, obviously, in living with someone for a decade, but things have evolved,” Kakacek says. “We trade off cooking dinner now. We have a domestic side of our life.”

Before recording their upcoming album SPARK, Ehrlich and Kakacek packed up their things and trekked across the country, from their hometown of Chicago to a Craigslist rental in Portland, Oregon. Ehrlich was emerging from an intense breakup, looking for a place to clear his head, and Kakacek followed in an attempt to escape the remainder of the brutal Chicago winter. It was 2020, and shortly after they arrived, lockdown was enacted and flights were grounded. The pair found quarantine to be an almost necessary step in their progression as a band, as it forced them to finally stop touring. “I think that spiritually, we needed to be locked away for a moment, to re-evaluate what we wanted to make and what was going to make us happy,” Ehrlich explains.

SPARK, which releases September 16, is a clear departure from the band’s previous albums, yet the record’s sound remains distinctly ‘Whitney’ with Ehrlich’s signature falsetto and catchy hooks. SPARK takes a more light-hearted musical approach than the duo’s past work: “There was a lot more head bobbing and dancing in the studio,” Kakacek says. “We were getting a little more playful.” This isn’t to say that the record doesn’t take itself seriously; there’s the heartache in “COUNTY LINES,” with Ehrlich singing, “Heaven knows / You and I / Only tore ourselves apart / Even those / County lines / Couldn’t keep you in my arms.” “TERMINAL” details the collective loss felt en masse during the pandemic. “BACK THEN” embodies the hope necessary to survive devastating pain and darkness.

The duo got their start playing small, DIY gigs; these spots often weren’t meant for shows, so they’d set up their equipment on the floor and play. “We had a community of friends who all loved our early demos, and we just ended up playing wherever they worked,” Kakacek says. “That eventually got us shows at proper venues in Chicago. It definitely felt like the community helped prop us up; the band started because of [them].”

Today, when the pair walks down the streets of Chicago, they get at least one Love the music, boys! from passersby. “It’s real hometown love,” Ehrlich says. When it comes to fan recognition, the only awkwardness stems from people mistakenly identifying Kakacek as Logic. Between Ehrlich’s laughs, Kakacek details a date he was on two years ago, where someone approached and asked if he was the rapper. “When people come over and like Whitney, I love it, but don’t come to me asking if I’m Logic. This is me putting everyone on blast.”

In SPARK, Whitney is translated to the present moment—something they struggled with in their sophomore album Forever Turned Around. In creating that record, the band found itself trying to replicate the success of its debut psych-folk album, Light Upon the Lake. Forever sounded similar, but the boys struggled to understand why it didn’t resonate the way it had before—they’d been making music as versions of themselves they had outgrown. In SPARK, the duo is unafraid to take a step into who they are now, and use new tools to do so; they intentionally avoided the acoustic guitar that had previously been the backbone of many songs, instead leaning into piano and digital instruments.

During the process of producing the album, Whitney went through multiple hardships on top of the pandemic itself: Both went through breakups and losses, including the deaths of Kakacek’s grandfather and of their shared mentor, Girls’s J.R. White. At their darkest point in the pandemic, the duo found themselves in a deep depression, and lost themselves in substances and self-medication. “[‘TERMINAL’] captures the point that we were at—sonically, in tone and mood, lyrically, sentimentally,” Ehrlich says. “I think a lot of people would have taken a break; I’m glad we didn’t.”

Luckily, their ad hoc studio in the Portland bungalow made for a perfect escape from the brutal realities of the world. “If we were stuck in Chicago, we wouldn’t really have been able to make the same album,” Ehrlich says. “It would have been a different type of depressing. It was nice to at least have a house and, I don’t know, we got to stretch out. We got to spread our depression out a little bit more.”