David Zwirner outpost 52 Walker proposed an all-Black staff—but should mega-galleries have a say in reforming the inequities they profit from?

52 Walker, a David Zwirner outpost led by director Ebony L. Haynes, opened in October of 2021 in Tribeca. Perhaps most publicized about the new gallery was Haynes’s early assertion that she planned to hire an all-Black staff. A 2020 New York Times headline, reading “A New Zwirner Gallery With an All-Black Staff,” overshadowed the slow work and interventions that the director planned to place in the blue-chip art sphere, sensationalizing, rather, the racial aspect of the gallery’s programming. The headline is clickbaity in the sense that the terms ‘David Zwirner’ and ‘an all-Black staff’ seem to lie in contradiction. Why would this mega-dealer, one of the largest players in a deeply problematic, deeply capital-focused, and deeply white industry, be the one to lead this initiative? What are the implications of such a thing?

Featuring artists of diverse backgrounds and career stages, 52 Walker is distinct from the Zwirner mega-art dealer ethos; while most commercial galleries exhibit a new show every month and a half or less, each show at 52 Walker lasts for three months, similar to the longer exhibitions typical to kunsthalles. Additionally, the works at 52 Walker are for sale, but the gallery does not represent artists. It works, rather, in tandem with other galleries, allowing artists to use the space for experimentation.

When Haynes talks about 52 Walker, she focuses on conversations that reckon with the role of the gallery and the politics of selling art—especially the ways in which certain clients, often people of color, are kept out of galleries’ conversations. She’s focused on giving Black people and people of color the opportunity to gain experience in the gallery space. On the other hand, in the same Times article, Zwirner was quoted as wanting 52 Walker to simply attract more young people of color toward the nepotistic, gilded museum and gallery pipeline: “Hopefully people can join the space and get poached.” By slowing down the pacing of shows and thinking deeply about the ways in which people of color are not afforded the same access to art spaces, Haynes is questioning the gallery as a concept—but it’s not clear whether Zwirner has the same intentions. Why question the industry that you profit from?

“A look from the Other—something like white sight—fixes us in the violence, hostility, aggression, and ambivalence of its desire.”

There are deep dynamics at play when a mega-gallery like David Zwirner funds a space like 52 Walker—a space that forefronts Haynes’s commitment to creating better access for Black artists and arts workers. 52 Walker’s focus on slow curation, on questioning the ways in which galleries can work, and on creating points of access to art for people who otherwise might not have the chance seems incompatible with the capitalist, white gallery space that an international institution like David Zwirner embodies. What’s wrong with David Zwirner is not Zwirner himself, but the cultures reproduced in the relenting search for capital gain; it’s the culture of the art gallery—the culture of capital that is intrinsically tied to the mistreatment of people of color, specifically Black people, in the United States.

It’s not breaking news that diversity in the art world is incredibly lacking. The pool of successful artists, curators, art leaders, and administrators is overwhelmingly white. Identity politics in the art ecosystem is present on all scales—especially when it comes to how art by people of color is discussed, sold, supported, and often fetishized by white dealers and collectors. In recent years, many art spaces have provided two-dimensional diversity efforts—performances of solidarity that contribute to the tokenization of not only artists of color, but also art workers of color. Haynes’s radical uplifting of Black art workers in the gallery space is unwaveringly important, but David Zwirner’s role in this is not inconsequential. Haynes has full autonomy over programming, but 52 Walker is still a Zwirner outpost, part of the group of international galleries that have deep stakes in keeping the art world the way it is—the way that benefits them.

It’s necessary to highlight the complex dynamics that money exists in—the money that runs 52 Walker, and the entire art world. Art workers of color need to escape the ‘white sight’ that determines where and what can be produced, and who does the producing. By white sight, I mean a lot of things: I mean the ways in which people of color serve the diversity goals of institutions as representations rather than people; I mean the conversations that white people have with each other behind closed doors, and the generational wealth that determines who’s ‘something,’ and who’s ‘nothing.’ Frantz Fanon famously wrote about Black identity being formed by the white unconscious; there must be a coherent sense of identity to create a Black self without white influence. As cultural theorist Stuart Hall writes in his 1996 essay “Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” a look from the Other—something like white sight—fixes us in the violence, hostility, aggression, and ambivalence of its desire.

“‘Decolonizing’ the museum or gallery does not simply mean hosting art by people of color, or raising people of color into higher positions that will not treat them kindly or with care.”

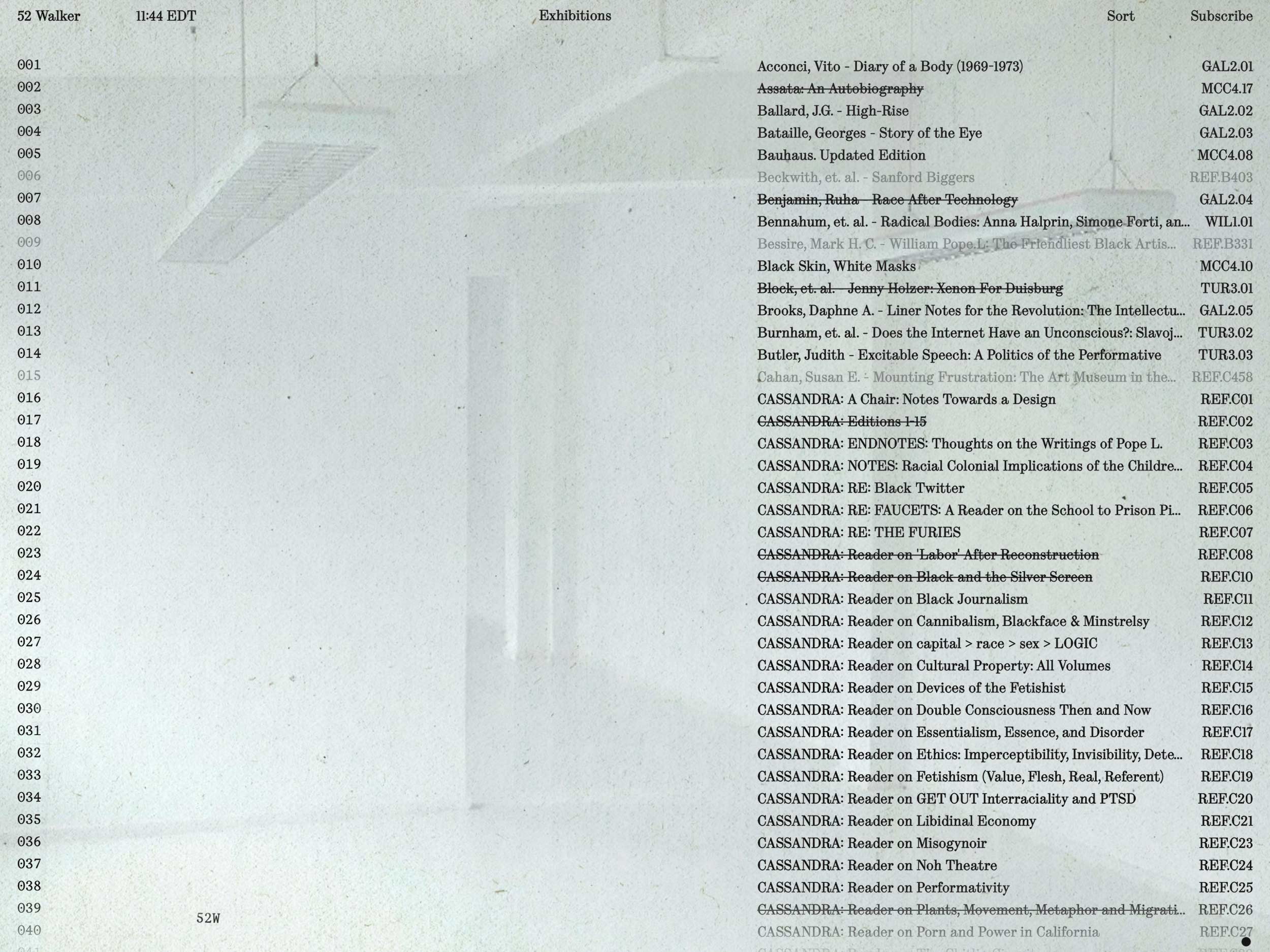

There are components of 52 Walker’s ecosystem that resonate as meaningful departures from the traditional gallery. You can apply for a free library card and check out the books in its curated collection—books chosen by the artist and the gallery to reflect the show currently exhibited, from Fred Moten to Slavoj Žižek, with lots of thoughtful and theoretically super-abundant titles in between. This library is an attempt to engage community in a space notorious for gatekeeping and class discrimination.

There’s a reckoning taking place, but not in the way you might imagine. This reckoning is slow, and it’s embedded within the greater David Zwirner mega-institution. 52 Walker doesn’t show ‘Black art.’ It embraces the complexity of cultural identity as a matter of becoming, approaching it on an individual basis rather than as a generalized category.

This is not to say that one should not act within the white institution; to act is of the utmost importance. It’s also not to envision the end of the gallery space, which is integral to the art world ecosystem—because artists need money to make art, and art workers need money to live. These spaces need to change. In that hope, the criticism of the sources of art spaces is incredibly important. The hardest thing to watch in the art world is people of color reproducing the same power dynamics inherent to white institutions. ‘Decolonizing’ the museum or gallery does not simply mean hosting art by people of color, or raising people of color into higher positions that will not treat them kindly or with care.

There is value in moving away from the institution, away from white sight—in building something outside of Zwirner and its peers. By working within the bounds of ‘representation,’ we are always working against it—in confronting dominant culture’s understanding of an identity, it’s further complicated. Identity is complicated. Art is one of the means by which one can see and be seen at the same time. Who is watching our interventions, and who is benefiting?