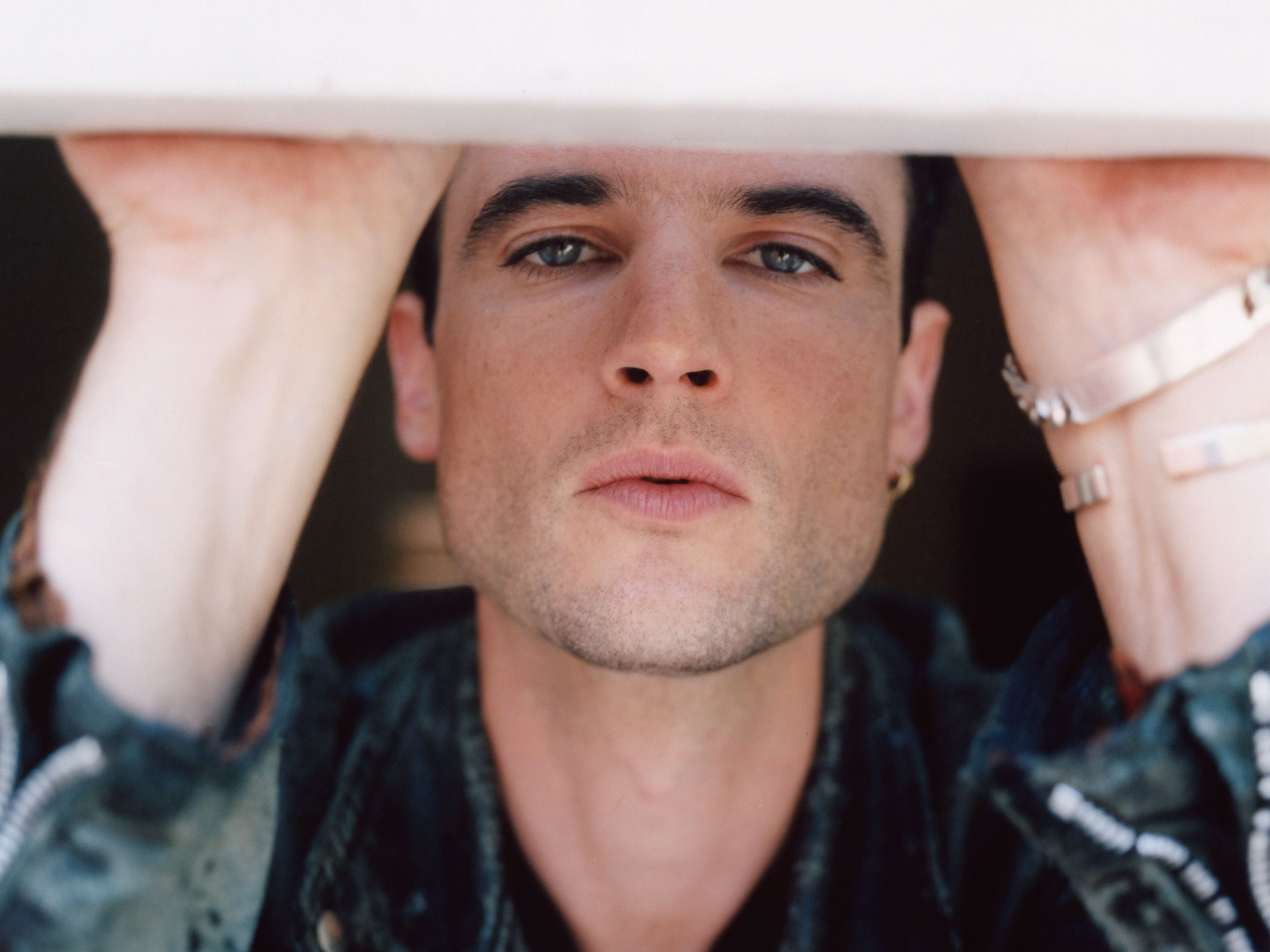

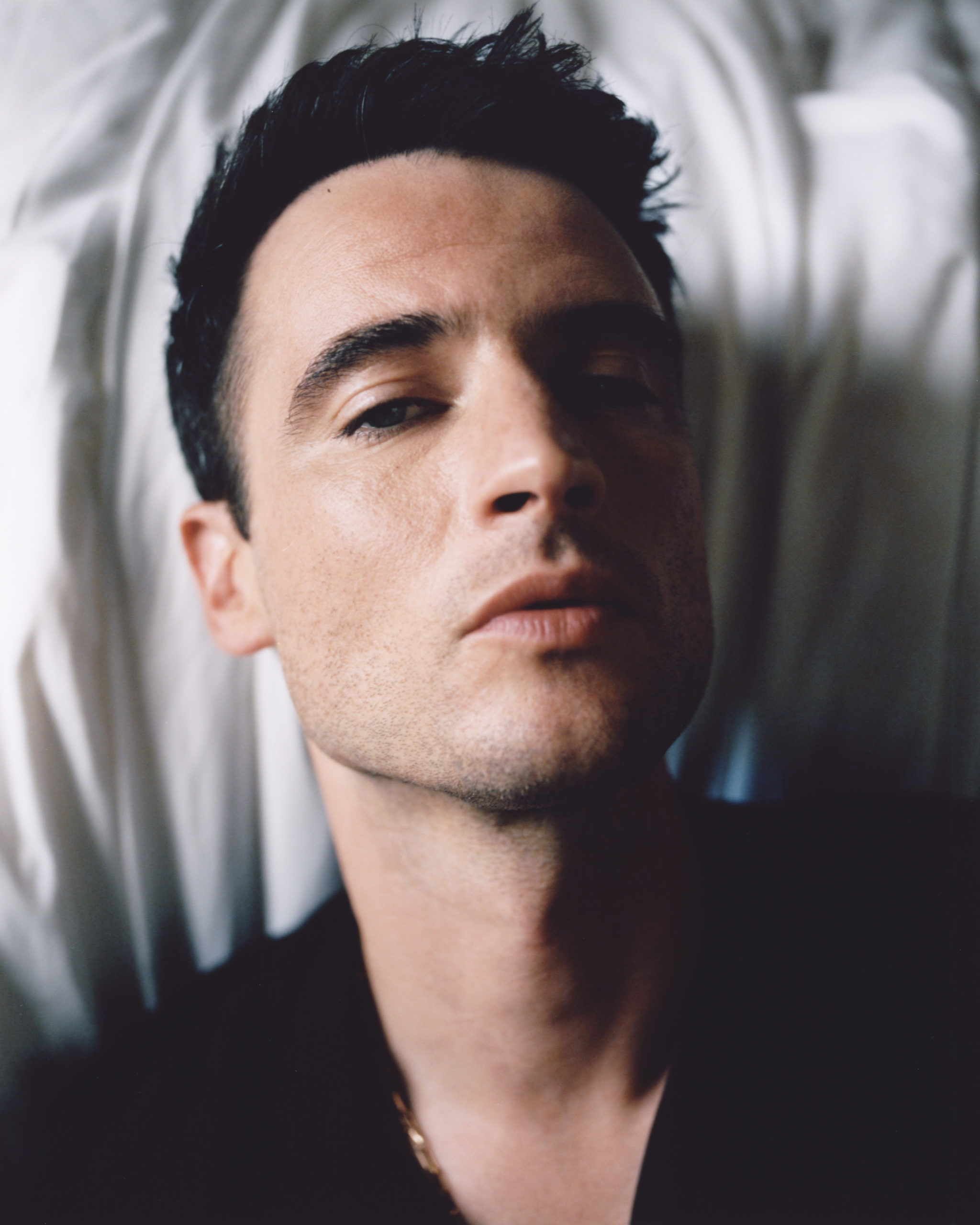

The actor joins Document to discuss his starring role in the long-awaited adaptation, seeking advice from Neil Gaiman, and his own lucid dreams

Tom Sturridge is naked inside an elevated glass sphere at the center of a massive room enveloped in unending archways. He’s uncharacteristically underweight and his pasty skin is almost glowing in the white light. He’s on set for Netflix’s The Sandman, an adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s graphic novels from the late ’80s and ’90s, which quickly reached mainstream popularity (a rarity for the genre). As he waits for the next take to begin, Sturridge attempts to find a position that is comfortable (for his own sake) and modest (for the sake of the crew), as it proved difficult to get inside the transparent orb—and apparently impractical to toss him a robe between shots. He had to be naked.

The actor, cast in the titular role, is in good spirits about the uncomfortable vulnerability his first weeks of shooting required. Perhaps, in part, it’s because he’s living out the fantasy of every kid who ever picked up a comic book: to become one of the characters that devoured and defined his youth. Sturridge’s Sandman is a cosmic being—more akin to a god than a superhero—who, in the actor’s words, is a “curator of the universe’s subconscious,” acting as the anthropomorphic personification of dreams and all that exists outside of reality.

The filmic interpretation of Gaiman’s fantasy horror world has been long anticipated, living in developmental hell for decades, since before the written series had even been completed. It was always too expansive for the time limitations of a movie, which it had initially been positioned as—a prospect Sturridge calls “stupid” and inconsiderate to the narrative. Now, the adaptation is realized in series form, allowing for an accurate portrayal of the story’s many layers.

Ahead of the series’s release this Friday, Sturridge joins Document to discuss becoming the Sandman, why dreaming that your teeth have fallen out doesn’t mean you hate your dog, and stripping down on set.

Megan Hullander: In adaptations of graphic novels, how closely do you think they should match the literature they’re based on?

Tom Sturridge: I think it depends on who’s involved in adapting it. When you’re a fan of The Sandman and you’re a fan of Neil Gaiman, really you just want to see him explore and expand on that. With [this production], Neil posed the question, ‘It’s 2021 and I’m making The Sandman again. What would I do differently?’ The answer is not much, because it’s a fucking masterpiece. But certainly some things, not only because of the way the world has changed, but also because, I think, even if you’re a superfan of the graphic novels, you want to be surprised—you want there to be a sense of danger, which I think can only come from new ideas.

Megan: This project was in developmental hell for decades—do you think there’s anything that resonates with this story now that’s different from the way it might have if it had been made earlier?

Tom: It’s always been ahead of its time in its exploration of gender and sexuality, and its representation of women. I think we live in a world that is far more prepared to interrogate those ideas. But I think it was in developmental hell because it’s 3,500 pages long. To make a two-hour movie out of it—it’s just a stupid idea. It’s inherently antithetical to what it is. The Sandman is a story about stories. And so the only way you can make a movie out of it, is to take one story out of it, which just destroys the whole meaning. It’s about the legion of stories, the legion of dreams, that all kinds of different beings have.

“He is a curator of the universe’s subconscious. If you create dreams, it means you know what people are dreaming. If you know what they’re dreaming, it means you know what they’re feeling.

Megan: Where did you feel like you had the most room to play creatively with this character?

Tom: This is going to sound really pretentious, but roll with me. When you’re building a character that already exists, it’s sort of like the difference between if you wrote a sonnet, compared to a piece of free poetry. Weirdly, when you have rules, it’s more freeing. I feel like I know what I’m fighting against. Whereas if someone says, ‘Do whatever the fuck you want,’ I find it limiting—because, actually, my first idea probably is not that interesting. It’s quite close to who I am, and quite small.

First and foremost, I’m a fucking fan of The Sandman; I care about it so much. I had no interest in having a new take on it. I just wanted to realize the movie that I’d already made in my head when I read it. I wanted to do justice to everyone else who cares about it as much as I do, [and base it] on the Bible that is those graphic novels.

Megan: Those imagined worlds people develop when reading The Sandman are obviously rooted in some similarities picked up from the books’s visual components. But I imagine that everyone has a varied interpretation of what the voice would be. Where did that come from for you?

Tom: It’s really scary. Because you think you know it so well when you’ve read all of it, and you suddenly realize, Shit, I don’t know what it sounds like. If you look at the graphic novels, his voice is written in white capital letters and black speech bubbles, and that does evoke something. But I very bluntly asked Neil, ‘What does he sound like?’ And he said that two things are really important: He’s thought every thought that’s ever been conceived. Therefore, when he speaks, it should be like it’s etched in stone. He’s not reaching for an idea. He knows exactly what he’s saying. And, he should sound like the voice inside of your head that asks you to go to sleep and leads you through your dreams—which is important, because in the beginning you look at the images of him and, as an actor anyway, you always kind of want to be like, [Batman voice] ‘This is what he sounds like.’ What it actually is has to be authoritative and dangerous, but it has to also be seductive enough for you to accept the invitation to dream.

Megan: How do you go about humanizing a character who’s so godly?

Tom: It’s all pretty abstract. I just asked myself the question, What is it that he does? He is a curator of the universe’s subconscious. If you create dreams, it means you know what people are dreaming. If you know what they’re dreaming, it means you know what they’re feeling. Therefore, he has to be extraordinarily empathetic. Because it’s the universe’s feelings; it’s a lot of feelings. What do you do when you feel too much? You push it down, you suppress it—you need discipline to control it. I think he comes across as introverted and isolated, because he’s someone who’s trying to control this wealth of emotion.

Megan: Have you become more cognizant of your own dreams since starting this project?

Tom: I’ve always had pretty good dreams. I enjoy dreaming. I think I’ve been aware of my power within them—that I am generating them, and therefore I can generate new images and ideas. I dreamt about him the day I got the part, [which was] really weird and incredibly satisfying. I’ve definitely tried to find him again—I haven’t.

Megan: Do you think about the meaning of dreams differently?

Tom: No. In my minor experience of dream analysis, I think it’s too light. Dreams are so complex, and in the depths of our subconscious. I think it’s unfathomable—the whole, like, Your teeth fall out, therefore you don’t love your dog.

“When you’re building a character that already exists, it’s sort of like the difference between if you wrote a sonnet, compared to a piece of free poetry.”

Megan: What is your process, in terms of getting into character? How did it differ from past roles you’ve taken on?

Tom: Firstly, I didn’t like the physical aspect of it. In the beginning of our story, he’s naked. I really wanted to figure out a way to physically articulate the fact that he wasn’t human. There are very specific images of him when he’s imprisoned in the graphic novels. I think of it as, like, he’s metabolizing dreams, and so he sort of has no flesh. Trying to achieve that was a new thing for me. It took months of kind of training and not eating, which was weirdly satisfying because, as we’ve already talked about, [the acting] is so abstract. So you create a character; it’s work and it’s luck. Whereas changing your body is like, if you do these three things, it will work.

Megan: What was it like filming that shot? Stripping down day one sounds sort of awkward. Or is it just part of the job for you?

Tom: It was embarrassing. I felt like a complete idiot. The glass sphere [I was in] was really difficult to open, so I couldn’t get out of it in between shots. It would waste too much time. Because it’s glass, you couldn’t have, like, a blanket in there in between shots. I just spent the entire time figuring out weird yoga poses to protect the other people. We did it for a month like that. And what was hilarious—at the beginning, everyone was really sweet about it. But, like, day eight, everyone was just like, [mimics them blocking their eyes in disgust], ‘Oh, for God’s sake. Again? Jesus.’

Styling Sarah Toshiko West. Hair and makeup Kim Verbeck.