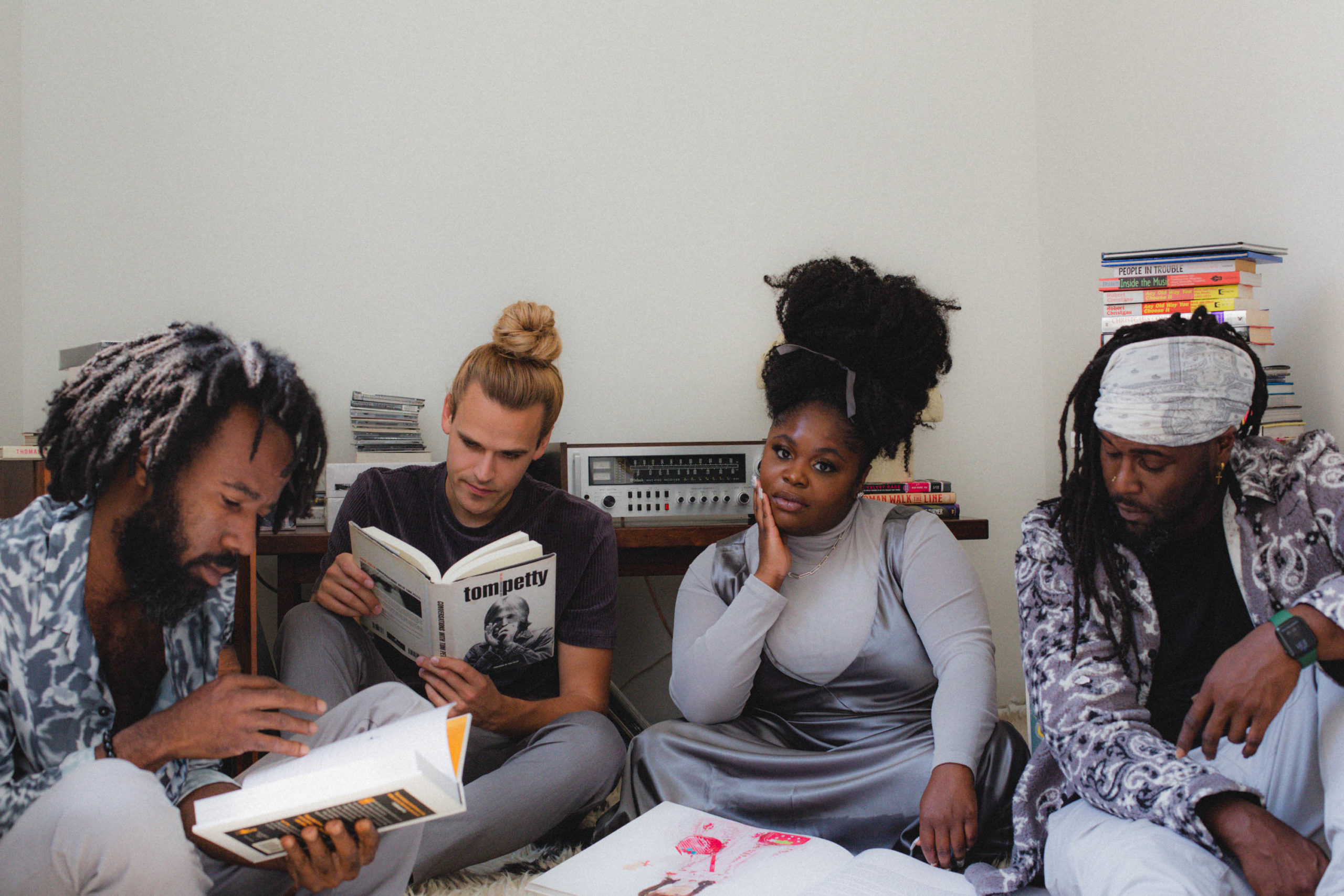

Tarriona ‘Tank’ Ball, the band’s lead vocalist, joins Document to talk about the state of modern soul and writing while the world burns

It’s fitting that Tank and the Bangas’ big break came through their NPR Tiny Desk Concert. The soul-heavy, genre-rejecting New Orleans band shone brightest in a live performance setting, and their sound and lyrics—undeniably modern—were prime fodder for the age of virality.

The undeniable electricity of that performance was only the beginning for a band that has gone on to push funk and soul traditions toward the future, while remaining grounded in the timeless fundamentals of technical mastery and delicate yet forceful lyric poetry. Their latest album, Red Balloon, realizes that mission through collaborations with a progeny of soul legends—Lalah Hathaway and Alex Isley, to name a few—and with lyrics that confront life during the overlapping crises of the pandemic, rising right-wing extremism, and the evils of the digital age.

Document caught up with Tarriona “Tank” Ball, the band’s lead vocalist, on a break from summer tours to talk about the state of modern soul music, sustaining a viral debut, and writing while the world burns.

Cole Cahill: Your latest album is titled Red Balloon, and the album before it was called Green Balloon. How are the two projects connected, and what sets this one apart from the last?

Tarriona Ball: Green Balloon and Red Balloon were going to be [one album] at first. But then we were like, Let’s wait ’til some years go by. Let’s see how we mature. Let’s see how time changes us. And boy, did it change us—so much to the point where they sound like two different bands. We never expected Red Balloon to sound like this. The difference is maturity and life experience. [Green Balloon] was still for being naïve and fresh and new. We were touring so much after Tiny Desk. And [Red Balloon] was that moment of alertness: Stop, pause, look around [at] the bloodshed, the lives lost.

Cole: Themes of politics, current events, and anti-Black violence thread through the record. How did you want this project to engage with those themes?

Tarriona: You can’t ignore what’s going on around you, whether [it’s] the anxiety within our youth, what’s going on at the Capitol, teachers [being] underpaid and overwhelmed, our healthcare. It’s pretty amazing to talk about all of it, but in our own Tank and the Bangas way, where we are not shoving anything down your throat—because it’s not like we have all the solutions. We’re just people, and we’re artists, it’s our job. Like Nina Simone said, ‘An artist’s duty is to reflect the times.’ And I think we did that with this one.

Cole: The song ‘Mr. Bluebell’ references the Capitol insurrection in January of last year. Can you tell me about the background of that song and how you wanted to respond to the attempted coup?

Tarriona: I don’t know if you remember, but at a certain point Blue Bell had a recall on their ice cream.

“We’re never gonna say, ‘That sounds too country, that sounds too R&B, that sounds too old-school.’ We’re gonna respect that song until it’s done.”

Cole: Oh, Blue Bell, like the ice cream.

Tarriona: Blue Bell had those recalls, and it was literally killing people—and people were still like, ‘Where is the Blue Bell ice cream? We want it back on the market.’ They didn’t give a damn. In America, if it makes dollars, it makes sense. And if it makes sense, it makes dollars. Blue Bell represents the taste of America.

Cole: So many songs on this album have a distinctly old-school soul sound, and you brought on artists like Alex Isley and Lalah Hathaway, both of whom are the children of legendary artists and have become legends in their own right. I get the impression you’re crafting a new generation of soul and funk music.

Tarriona: I honestly never thought about it that way, when we’re making the music. We respect the flow of the music. We’re never gonna say, ‘That sounds too country, that sounds too R&B, that sounds too old-school.’ We’re gonna respect that song until it’s done. We leave it alone. We are not going to ever shy away from any genre.

I think that ‘Stolen Fruit’ was such a change for us. We started making ‘Stolen Fruit,’ [and] everything that followed after it had this beautiful vibe of quality, vintage soul music. And then, we were just around the children of prodigies. It was the most amazing, most special thing, that all these musicians and artists [came] in and out just leaving their vibe, even if they don’t say a word, just the energy.

Cole: It’s interesting how the album combines such a retro sound, with really direct engagement, with the qualities of life in the modern world. How did you want this album to interact, both sonically and thematically, with the time we’re in now?

Tarriona: I just remember being here, sitting on the porch, thinking about all that was going on. And when a label says it’s time to make another album, I’m like, What the hell am I gonna write about? I feel filled with so much, but also disconnected from everything—because you’re away from the world, you’re just watching everything through a little screen. You could literally see a shooting and then the next second see a makeup tutorial. That’s how much they’re messing with the minds of the people. And we don’t realize it, because we’re just on our phone. Everybody is. And everybody used to talk about—growing up in church—how the mark of the beast was gonna be a mark on your forehead, or a credit card on your wrist. How about the phones? How about something that we look down at and, and never look up [from], you know what I’m saying? We rarely look up at the sky anymore. It messes all of us up in some type of way.

Cole: Live performance is so core to what you’re doing. You’re back on tour now after a hiatus during the pandemic—how has the experience of returning to audiences felt?

Tarriona: The fans were excited and ready. We receive more love in places that we were used to the crowd being pretty serious in. We could tell that people were ready for the live music to be back.