Anxieties surrounding the virus’s physical manifestations display society's aesthetic obsessions

As of this week, New York City is in a state of emergency due to the rise of monkeypox––a virus transmittable through close contact with those infected or contaminated objects. According to the CDC, there are now about 7,102 cases in the US, and 1,748 in New York state. But the number is probably higher, as many cases go unrecorded due to a lack of resources and knowledge concerning the virus, despite the government’s long-standing awareness of the disease’s existence as it first emerged in the ’70s. Monkeypox’s sudden spread prompted a sense of déjà vu, as it closely follows the rise of COVID-19. Only this time, people are more concerned––not because of its physical implications, nor because of the lessons learned from the pandemic, but rather, for the aesthetic threat it poses.

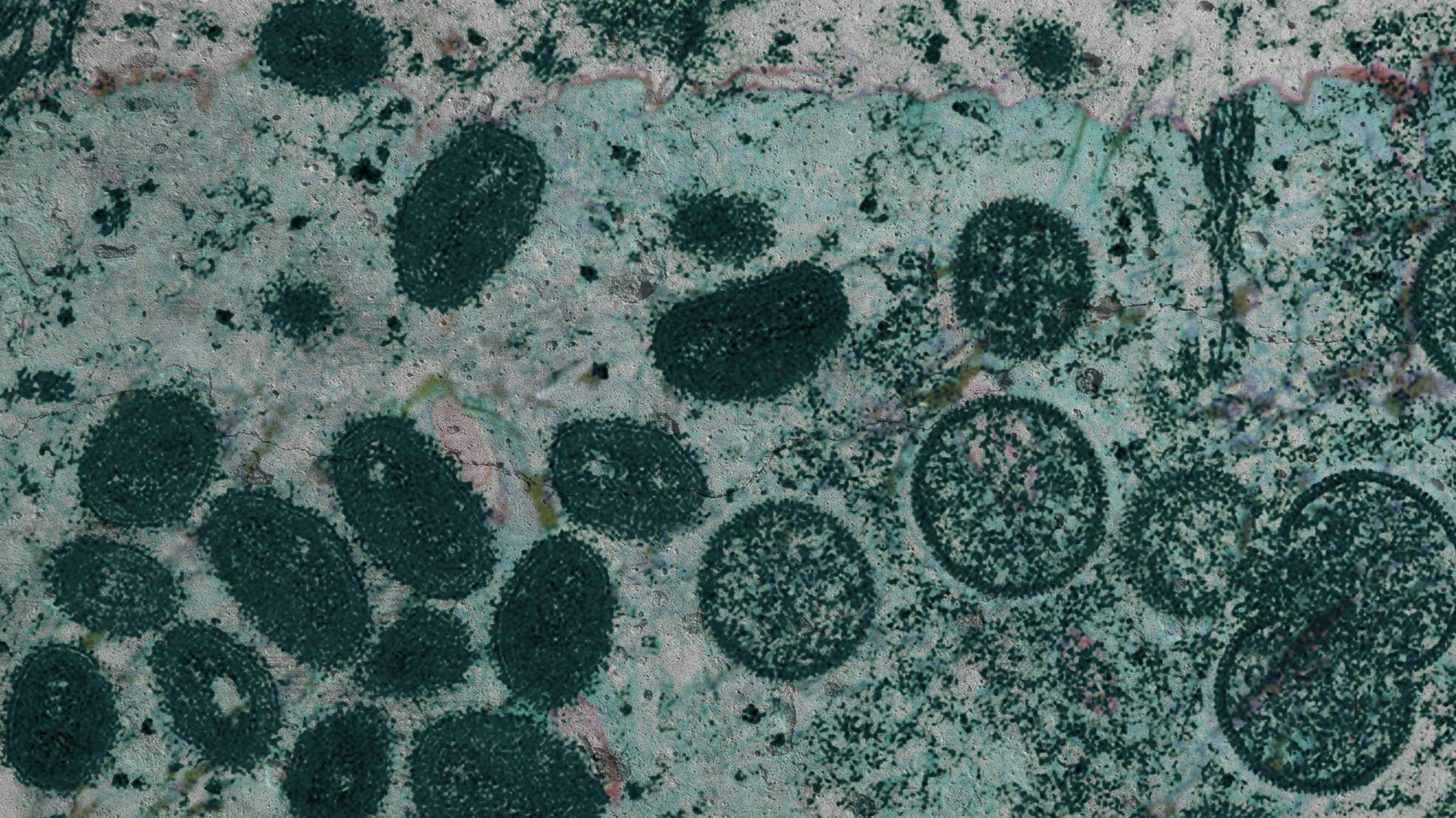

Monkeypox is a virus similar to smallpox, which usually causes a fever, malaise, headache, and swollen lymph nodes before a rash breaks out. The lesions start out flat, possibly appearing inside the mouth before spreading to the face and rest of the body. Within a few days, those lesions become raised, building up with a fluid that eventually turns an opaque yellow color. Itchy scabs appear for about two weeks as the rash heals, but may leave behind hyperpigmented patches and pitted keloid scars.

Many people, including those who were unafraid of the impacts of COVID-19, are now expressing a fear of monkeypox. Twitter user @gloless tweeted, “covid was cool but this monkey pox shit make you ugly i can’t take that risk,” which quickly acquired 11,200 retweets. Another Twitter user, @piercespears, shared his sentiment: “Monkeypox is definitely scarier than covid idc.. I can deal with early onset Alzheimer’s but I draw the line at scars on my face.” They even replied to the initial tweet with, “Not people saying you care about looks more than believing alive. UM YES?” On TikTok, leah_s16 posted a selfie video with text reading, “I work too hard to keep my skin clear for it to be destroyed by monkeypox. Monkeypox may not mean ‘deadly’—doesn’t mean I wanna get it. I dont wanna have ugly skin for the rest of my life.”

Monkeypox is a virus similar to smallpox, which usually causes a fever, malaise, headache, and swollen lymph nodes before a rash breaks out.

This sort of ‘edgy’ humor is expected on Twitter and TikTok—it may even be a staple of the platforms—but even so, these messages carry an element of unfiltered honesty, one that displays broadscale cultural values. Beauty, especially by Euro-centric standards, remains another form of what French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu calls cultural capital. He coined the term to describe conditions that may be converted into economic capital, and ultimately a higher class bracket. Bourdieu explains that there are three forms of cultural capital, one existing in the form of “long-lasting dispositions of the mind and body.”

In a capitalist world where Kim Kardashian proudly announced she might integrate poop into her daily diet if it meant she’d look younger, it is clear that beauty functions as another form of currency. For the wealthy, there are practices like plastic surgery, makeup techniques, and skincare remedies for a chance at getting closer to meeting these standards of beauty, and thus preserving their social standing. For those who can’t afford the luxury of physical alterations, apps like Facetune are built to hide anything that might be labeled as imperfect. It’s easy to dismiss superficial notions of beauty as outdated, but beauty remains a class identifier that is always on display, especially as the internet exists as an extension of one’s self. The more you conform to these notions of beauty, the richer you are in both tangible and intangible ways.

Monkeypox, it seems, poses a threat to such social currencies. A diagnosis comes with a chance of becoming “unattractive,” ultimately leading to a decline in one’s current class limiting the advantages they used to receive. Anxiety over monkeypox is a result of our current conditions, rather than pure selfishness. This outbreak exemplifies the work that still needs to be done within beauty politics.