Baz Luhrmann’s ‘Elvis’ revives debates around pay, appropriation, and who benefits from rebellion

Challenging accepted standards of filmmaking by mixing multimedia documentary snippets with high-stakes cast performances, Elvis (2022) tracks the King of Rock ’n’ Roll as he skyrockets to stardom, and follows the unceasing threat of death that looms over him. The discourse preceding the film’s release remained at a standstill, with split public opinion on the life and legacy of Elvis Presley. Discussions about the musician were halted, as there weren’t any reasons to talk about him.

To many, the man with the hypnotic hips and the sultry voice was the epitome of what America stands for—or, more precisely, what it could have been. He was the leading figure of a bygone generation, but his influence hasn’t faltered: Fans still dress up as Elvis for Halloween and decorate their refrigerators with magnets of him. A mesmerizing singer with a voice like no other fell to the lurching steps of fame.

Elsewhere, Presley is perceived in a harsher light. Many see the artist as merely a handsome white boy who benefitted from the oppression of Black people. A boy with a manager who spied on local Black singers in rural areas, with voices smooth like wine and as powerful as liquor. The hymns and blues that Black people sang to find sanctuary in slow-going pain were turned into jigs that white crowds could swing their arms to. They’d never be given a chance to expand the reach of their talents, because one thing more powerful than skill is hatred.

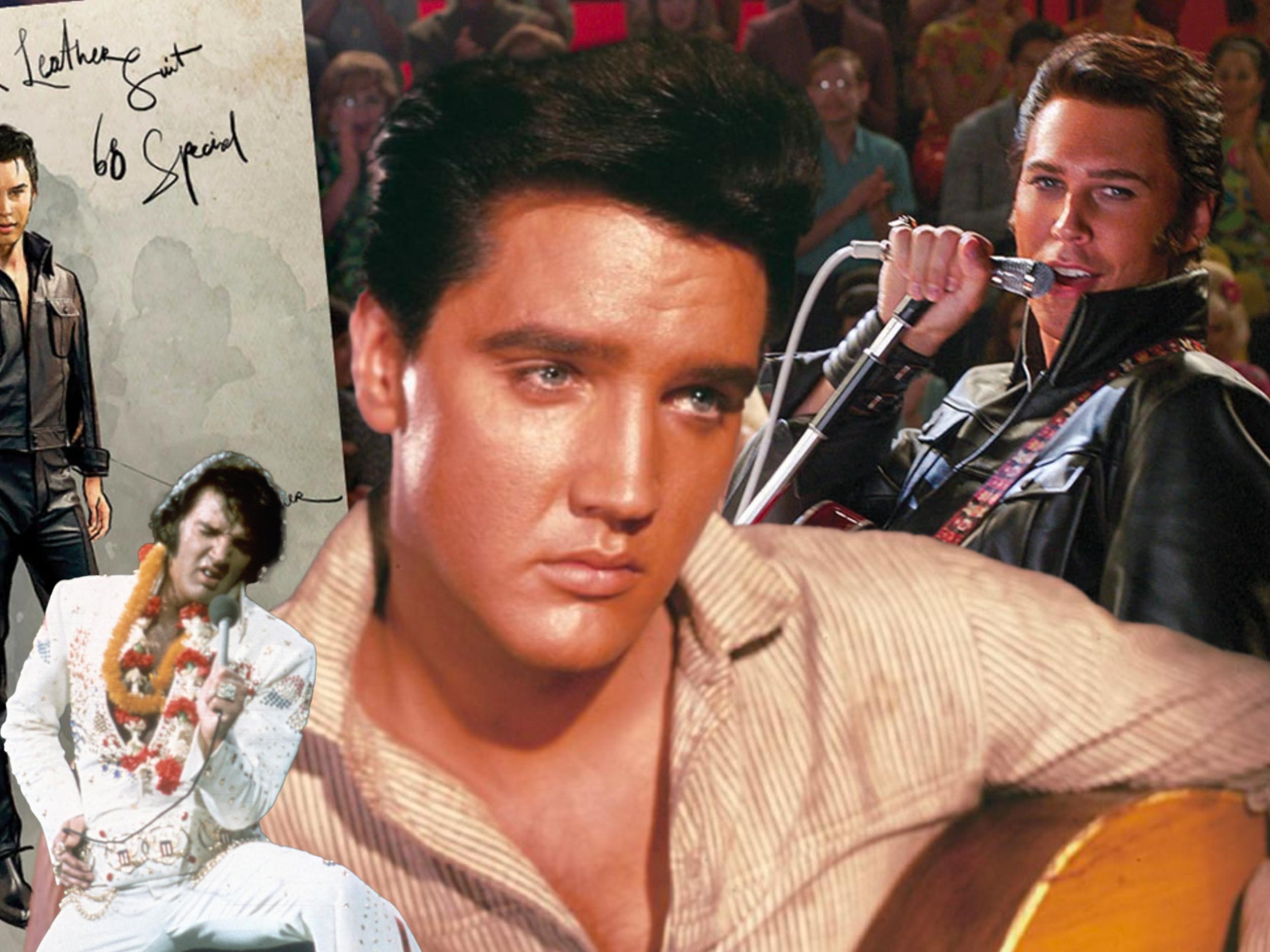

Now, this film comes out—the latest interpretation of Elvis’s rise and fall. Austin Butler’s performance as the singer is bold and emotional. Through each song, you can see the intersection of what Presley meant to audiences, and what he means to Butler. The film perfectly captures the toxicity of the music industry and the way it strips its brightest stars bare. Regardless of where you stand on Presley, the feature forces empathy, displaying him as flesh-and-blood—as a star who just wanted to make it.

“The hymns and blues that Black people sang to find sanctuary in slow-going pain were turned into jigs that white crowds could swing their arms to.”

Nonetheless, Baz Luhrmann’s sympathetic representation of the singer can’t bury the prior debate. Throughout the film, the director makes evident the complexity of Presley’s relationship with Black people. In the film, he is inspired by other artists, drawn to the music of blues singers. His actions read as less appropriative because he lived among Black people, regardless of the segregated times. The film explicates the Jim Crow era by depicting the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy. From Elvis’s point of view, Presley reshaped the conversation around race; the film favors a more nuanced and complimentary view of the artist, in which he gives back to those he took from. It depicts a Black community that loves him because he was putting their songs on the charts.

In a late interview, Eddie Rabbitt shared how he was recording a song at the same time as Presley. His manager told him to allow Presley to claim it, because that would ensure money and the track’s popularity. They ended up sharing 50% of the royalties with Presley’s manager, Colonel Parker, and Presley took the other half. Rabbitt was appreciative of this arrangement, as it was a quick ticket to compensation. As a white singer, he was able to compromise with Presley in exchange for popularity. Black singers, on the other hand, were forced to compromise with Presley for acknowledgement of their existence. Every time Presley would get on stage, mimic their moves, and sing their songs, Black artists were reminded of their cultural significance. To see white audience members screaming word for word the lyrics they wrote—albeit through Presley’s voice—was as big of a win as segregation times could offer.

Allegedly, Elvis recorded over 600 songs, and there wasn’t a single one with just his name on it. He was always collaborating. A majority of Elvis’s songs were covers, and the time over which they were made—from the ’50s through the ’80s—was the era of covers. Famously, Aretha Franklin covered Otis Redding’s “Respect” in 1967; “Surfin’ USA” was originally written by Chuck Berry and Brian Wilson in 1958, but went on to become a tropical anthem when it was adopted by The Beach Boys in 1963; “Woah, my love, my darling”—the introductory lyrics of one of the most hauntingly romantic songs ever, “Unchained Melody”—was sung in 1955 by Todd Duncan, but rose to greater fame when it was covered in 1965 by The Righteous Brothers. In 1977, at the Market Square Arena, Elvis performed “Unchained Melody,” cementing this song in history as one of the last he ever performed before his passing in August of the same year.

“In this new age, ownership is all an artist has. Compensation holds value, but proprietorship is power.”

The alliance between the influence of Black culture and Presley’s performance didn’t go unnoticed by the government or the mainstream media. Elvis’s appropriation of Black flamboyance wasn’t politically accepted early on in his career. His signature swagger combined gyration and deep rhythm with mannerisms that were blatantly taken from Black men. The film depicts his arrest in Memphis, Tennessee for ‘vulgar dancing’: The police rallied around the stage to intimidate, and once Elvis shook his legs and rolled his groin, they immediately took action. Presley could cover artists—regardless of whether the originators were musicians of color—as long as he didn’t perform like one. In real life, he was threatened by the state of Florida on account of his dancing; the music was never the issue—it was the perils of Blackness sewn into his mannerisms.

News and music publications wanted Elvis’s Black influences to be erased, as they considered his performances to be brainwashing young white teenagers. The sexualization of Presley’s performances emphasized early Buck stereotypes made against Black men. Elvis’s fans celebrated him for his rebelliousness: the choice he made to continue to perform with a sort of cultural ambiance. Some of the Black community of this era—and those unseen musicians—applauded him for carrying on their songs, as they felt it might be the only way they’d be heard. Those musicians included Little Richard and Chuck Berry.

But does circumstance excuse appropriation? In recent years, social media has become an arena for public cancellations, and for publicizing lawsuits against corporate and higher-up artists, musicians, and business owners. From beats to designs, many underground creatives have pleaded their claims to proprietorship, as their artistry has been “borrowed” from. In this new age, ownership is all an artist has. Compensation holds value, but proprietorship is power.

Our current generation is far different from the communities that lived through the mid- to late-20th century. As decades passed, the fight for equity, respect, and credit has strengthened, and Black people aren’t settling for less. Black creatives are taking to social media to discuss the legacy of Blackness—from hairstyles, to clothing, to vernacular language—to combat the imperialist mindset which believes that the talents of marginalized people are to be sacrificed for the success of oppressors. Creations that the masses would call “ghetto”—acrylic nails, gold teeth, baggy jeans—have been reinterpreted and whitewashed, discrediting their rightful owners and often straying far from their original intent.

“Perhaps today, the question isn’t whether or not Elvis stole from Black artists, but rather, whether they knew they didn’t have to be borrowed from?”

Without the enforcement of ownership, higher-ups take advantage, as the mainstream following won’t know the difference. Which begs a greater question: Would Elvis’s legacy still be as bright if he had lived in this generation? Would Black musicians like Big Mama Thorton, Yola, and Little Richard still hold Presley to their mantle if they knew they could shine on their own? Regardless of Elvis’s individual talent, would his anchored position as the King of Rock ’n’ Roll still be intact if the underground musicians he took from knew they were also in the running for such a momentous title? That their legacies could stretch farther than local bars?

In Elvis, Presley’s greatest comrade, B.B. King, hangs over the window ledge, as the star looks out over the city, reminding him of the power he doesn’t have. He’s conflicted and unsure of how to authentically be himself. King speaks to Presley with acceptance of his place as a Black man, whose opportunities would always be sliced in half. This is supposed to make Elvis fight harder, as he becomes aware that he represents the opportunities Black musicians will never get. The golden ticket would always be just millimeters out of reach. This was the reality of the Jim Crow era. Second class and second place. If only they knew it wouldn’t last forever.

It’s a bittersweet exchange to know that some lights may have dimmed because Black people were swindled into believing that they wouldn’t be loved on their own. And this wasn’t because of Presley, so much as what he represented: American success and the sacrifice of patriotism. Perhaps today, the question isn’t whether or not Elvis stole from Black artists, but rather, whether they knew they didn’t have to be borrowed from?