In a portfolio for Document, the two Sufi practitioners channel their spirituality as grounds for creativity

“I believe that, on some level, hearts recognize each other in ways that we are not necessarily aware of,” responds Nevine Nasser to Suleika Mueller regarding the instant connection they felt upon meeting each other. “This ‘heart knowledge’ is a big part of what I would define as Sufism. Sufism is generally understood to be the mystical heart of Islam.”

Both Mueller and Nasser are dedicated Sufi practitioners, who incorporate these beliefs into their creative work—Mueller as a photographer who specializes in Islamic stories hidden from Western mainstream media, and Nasser as an architect who explores the relationship between sacred structures and spiritual experiences. For her doctoral research project at the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts, Nasser transformed an old Victorian shop front in London’s Bethnal Green into the School of Sufi Teaching. The organization opened in June 2021, and has become a community center for the Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī Sufi order. It’s a place where members come together to meditate, study, and pray.

“Sufism is the mystical Islamic belief and practice in which Muslims seek to find the truth of divine love and knowledge through direct personal experience of God,” says Mueller. “It is a body of religious practice characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ritualism, asceticism, and esotericism, consisting of a variety of mystical paths that are designed to ascertain the nature of humanity, and of God, and to facilitate the experience of the presence of divine love and wisdom in the world.”

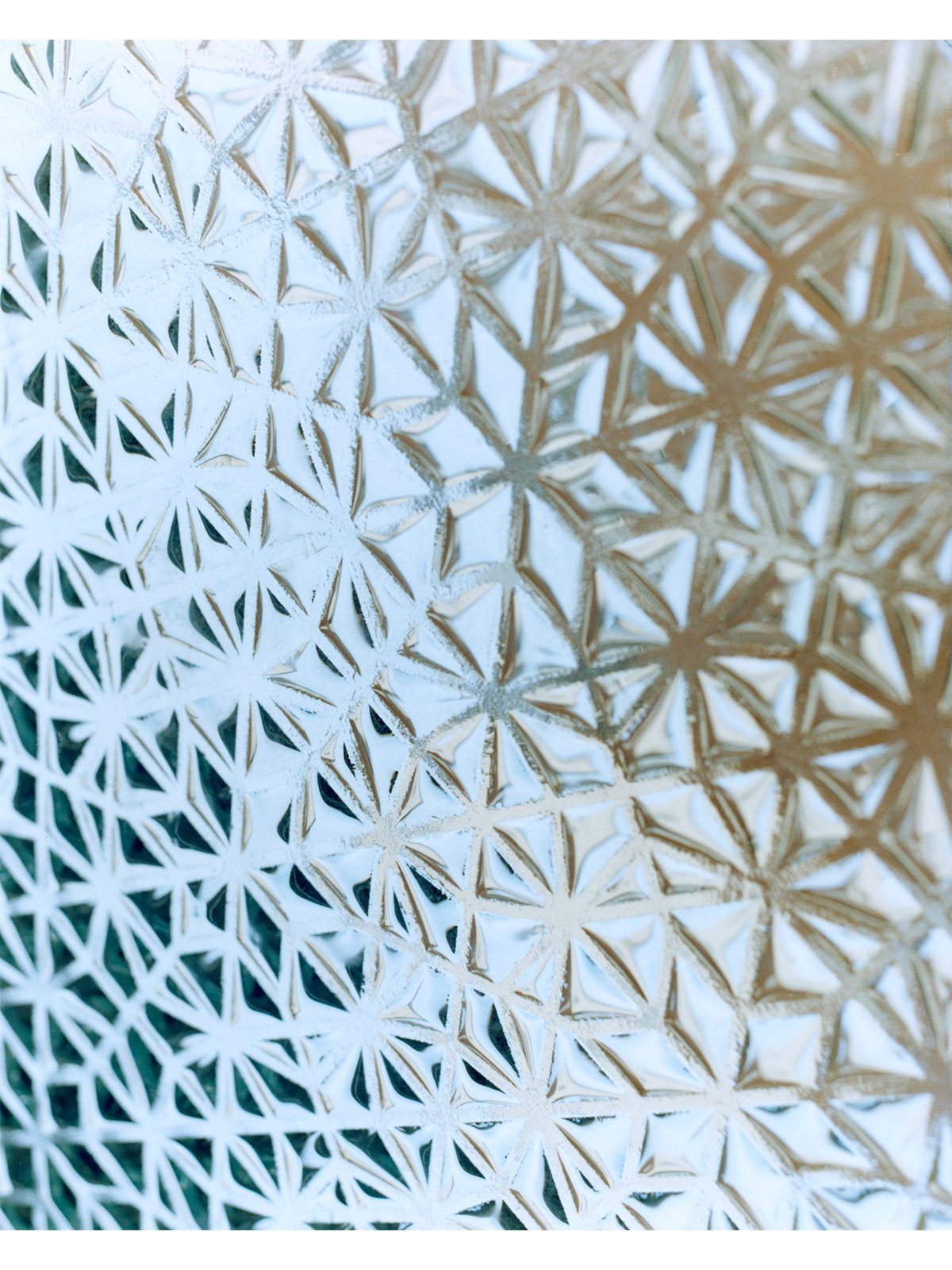

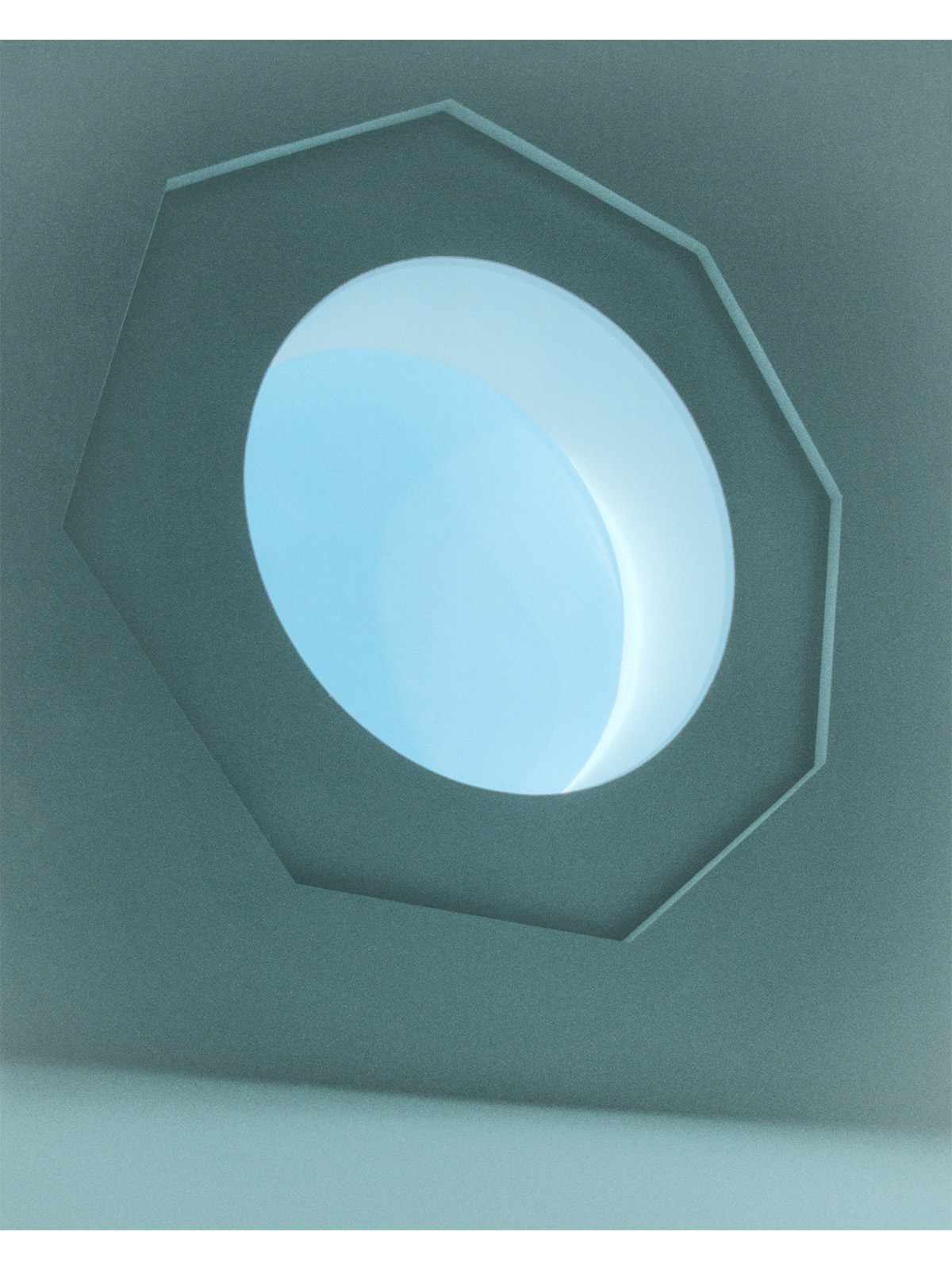

Together, the women explore the intimacy behind Sufism. Mueller captured Nasser within the zawiya––space––she created for the Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī order. The photo series is delicate and divine, with shades of serene blue and ravishing gold. Mueller’s details emphasize Nasser’s usage of symbolism, sacred geometry, and the Quran’s understanding of light. Some shots picture Nasser in action, performing the necessary rituals to create a profound encounter with God.

For Document, Mueller and Nasser met to discuss Sufi practices, the role of Muslim women in contemporary society, and geometry as a visual language that bridges the physical with the spiritual.

Suleika Mueller: When I first met you, I felt an instant connection to you not only because of our shared Sufi background, but even more so because, at the core of both our creative practices, is the goal of evoking transcendental experiences. I’m curious to hear what your definition of Sufism is.

Nevine Nasser: I believe that, on some level, hearts recognize each other in ways that we are not necessarily aware of. This ‘heart knowledge’ is a big part of what I would define as Sufism. Sufism is generally understood to be the mystical heart of Islam, but I believe that, within every human being, irrespective of religion and in different degrees, is an urge to experience a spiritual reality. Sufi practices are designed to awaken, transform, and develop the heart’s infinite capacity to plumb the universe of consciousness as a means to self-realization, and cultivates an awareness of the divine presence in every living moment. A person can become a dynamic, transformative force in the world, on all levels. In my experience, Sufi practices ultimately foster your ability to love, to be compassionate, responsible, and of service to yourself, family, community, humanity, or the world as a whole. If we want to simplify all that, I would quote my shaykh Hazrat Azad Rasool, who said, ‘Sufism is nothing but inward and outward sincerity.’

Suleika: I know certain practices are common amongst most Sufi orders, but I’m also conscious of how much Sufi practices differ between orders, having had the privilege of practicing with quite a few throughout my life. In my own order, there is quite a big emphasis on music—using chanting and dancing as a way to reach transcendental states of mind. However, the practices of your order seem to be much more silent and inward, which I find intriguing. Could you talk me through some of your rituals and practices, and their purposes, goals, and effects?

Nevine: The principal practice in the Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī order is meditation, muraqaba, which functions experientially by transforming a person’s subtle centers of consciousness, lata’if. There is no specific posture—we simply sit comfortably in a quiet place, state an intention, and wait for blessings. The meditation practice starts with transforming the heart’s subtle center, qalb, whereas most other orders begin with the self. Starting with the heart automatically affects the other centers, which further supports the process of spiritual transformation. Other practices are gradually added, which together create a spiritual balance that aims to purify the heart and the self, and cultivate a deep connection to the divine.

Suleika: There is much debate about the role of women in Islam, and it seems like an increasing number of people are opinionated and prejudiced when it comes to this topic—even if they are not very familiar with Islamic culture. Beyond Islam, across the world and throughout history, the majority of prominent spiritual figures have been male. In some cases and cultures, women were even considered incapable of spiritual development. One of the reasons why working on this project with you has meant so much to me is because it feels cathartic to depict a female spiritual practitioner, even more so because you are a Muslim woman.

What has your experience as a Muslim woman been like, especially within your order, and are there any common misconceptions you wish to clarify? Do you think it’s important to have more visibility of women’s spirituality in general?

Nevine: My experience growing up in Egypt as a female was challenging in that way. I felt limitations to my personal freedom, which stifled my development as a human being, leading me to eventually move back to London, where I was born—only to find that it exists here, too, but in a different way. When I started the Sufi practices, I still had these issues in my heart, but they were very quickly resolved. This was not an intellectual or even conscious process; it happened naturally and spontaneously, through the heart. I attribute this change to the spiritual practices that naturally healed inner aspects of myself—my ego—that might have been stuck. Also, the outward environment of the group and the shaykh supported that healing process, as they actively promote gender equality. Men and women have exactly the same spiritual potential, perform the same practices, and are given equal responsibility within the order.

There are many historic stories of great woman in Islam, and of female Sufi saints, but [they] tend to be out of sight and need to shared more. The tide is turning in relation to contemporary Muslim women.

Suleika: I love how you use art as a means to evoke experiences of the divine. I believe that both art and spirituality can challenge our perceptions and lead to an expansion of consciousness if properly approached. Photography has always been a means for me to communicate spiritual values. Can you tell me how you approached the design of the School of Sufi Teaching, and what elements you used to support people in their practice?

Nevine: The brief for the design was to create a space that reflected the essence of the Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī spiritual practices. The project came about during my doctorate, which explored the connection between sacred space and spiritual experience through practice. It was very timely! Through my research, I wanted to relink with the transformative quality of historic Islamic sacred architecture, which I felt had mostly been lost to contemporary buildings. The project became the perfect opportunity for me to bring my creative and spiritual practices into greater alignment. Through the study of historic buildings, I developed a framework that looked at key elements—symbolism, geometry, light, and sound—and how they were utilized in an integrated way in designs that bridged the physical and spiritual realms. I found that, in building these ‘bridges,’ experiences of the divine can be evoked through art and architecture.

Suleika: Every time I’m in the space, I feel deeply affected by the harmonious design, geometric patterns, intricate calligraphy, and deliberate use of color and light. The space makes me feel calm and focused—relaxed, but deeply aware and alert. After our shoot, when I printed the images in the darkroom for an entire day, I had a transformative, transcendental experience in my meditation practice; it’s as if the images penetrated my consciousness, and opened me up to something much deeper.

I’ve definitely had many transformative and expansive experiences through art and architecture, ever since I was a child. They are probably the reasons why I felt compelled to pursue a creative career. Would you say that it was similar for you? Have your personal experiences of the divine directly informed your work as an architect?

Nevine: Yes, it is the same for me. In a sense, undertaking the doctorate was my way of trying to understand these transformative experiences. I studied a specific set of buildings that had evoked these [feelings] in me throughout my life. Through my studies, I came across interesting research that described the spiritual effect of traditional art in terms of a ‘circle of communication.’ An artwork embodies higher qualities, experienced by the practitioner, which are radiated and externalized through the artwork to be experienced by others, which completes the circle of communication. Perhaps we can think of transcendent experiences of art as a sort of facilitated engagement with the cosmos and the divine, which extends from the creative practitioner to the visitor. Where the language of art—whatever form that may take—embodies an intrinsic capacity to activate the imagination, thereby linking human microcosm to macrocosm.

Suleika: Islamic art is deeply meaningful and symbolic. Sacred geometry is believed to be the bridge to the spiritual realm—an instrument to purify soul and mind. I know many spiritual concepts are represented in patterns, oftentimes acting as windows into the infinite, reminding of the greatness of Allah. Can you talk a bit about sacred geometry and its meaning in Islamic culture? I would love for you to explain the concepts behind some of the patterns you used in the School of Sufi Teaching.

Nevine: I undertook my doctorate at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts in London, where the principal teaching is sacred geometry. Participating in the geometry sessions, I had the opportunity to experience this function of geometry as a link between the physical and spiritual realms. Architecturally, when geometry is used together with light to express specific symbolic meanings, the effect can be very profound, even if we have no knowledge of the meaning. It is as though it has its own ‘transmission,’ which we feel in the heart. In Islamic culture, geometry is used as a visual language to explore the mathematical harmonies between human beings, the natural world, the cosmos, and the spiritual realm. It is underpinned by the belief that the world unfolds from God in a knowable way. Traditionally, the combination of architectural form and geometric pattern was considered a practical, visual dialogue between art and science, where geometry expressed experimentation with emergent mathematical and philosophical theories. It played an important role in metaphysics, in describing the order of existence and the nature of creation as a manifestation of God. It is considered the organizing principle underlying traditional Islamic design. At the same time, it is like poetry or music, capable of activating the imagination and inspiring intuitive connections to the spiritual realm that can lead to higher states of being.

In the School of Sufi Teaching project, a single geometric pattern was utilized throughout the building to create an overall sense of unity and interconnectedness. The pattern was developed as a panel years earlier by Katya Nosyreva, as a visual representation of the Naqshbandī-Mujaddidī spiritual path. The panel depicts the dynamic process of spiritual progress through 10 subtle centers of consciousness, laṭā’if. It has since become the ‘signature pattern’ of the order and has been used in a variety of contexts.

In the context of this project, the pattern is interpreted to symbolize the laṭā’if as subtle fields emanating from the Divine Essence. Accentuated stars symbolize the manifestation of individual laṭā’if within a person. Inside the building, the vertical grid that runs through the centers of the stars is interpreted to symbolize the flow of divine light, descending from the Divine Essence during spiritual practice, which activates a person’s laṭā’if. When the pattern is used in spaces that face the outside, the meaning changes—the lines are now horizontal, which is interpreted to symbolize a latent state of potentiality, where a person’s subtle centers are yet to be activated through spiritual practice.

Suleika: Do you have any advice for people who are interested in exploring Sufism further?

Nevine: I would advise that any interested person, after doing some appropriate research to make sure the group is authentic, seeks out a local group and tries the practices for themself. Sufism is an experiential path and I feel it is important to rely on personal experience to decide whether it is right for you. Try the practices for a few months and see. Avoid spending too much time reading and researching. The same is true for any spiritual path, although some do focus on stimulating the mind more than others.