The artist joins Document to discuss ‘Perfect,’ his iconic party paintings, and breathing life back into New York’s downtown

To be perfect is to possess all the desirable elements, qualities, or characteristics one can have. To be perfect is to be as good as is possible to be. To be the perfect downtown Renaissance man is to be Spencer Sweeney.

After graduating from Pennsylvania’s Academy of Fine Arts in 1997, Sweeney moved to New York City and never looked back. He became integrated with—eventually essential to—the city’s underground culture. He was a painter, DJ, curator, drummer, Aikido instructor, and even a nightclub partner with Andrew W.K. and Larry Golden. He ran with the indie it-crowd, but created a sense of community for outsiders, too.

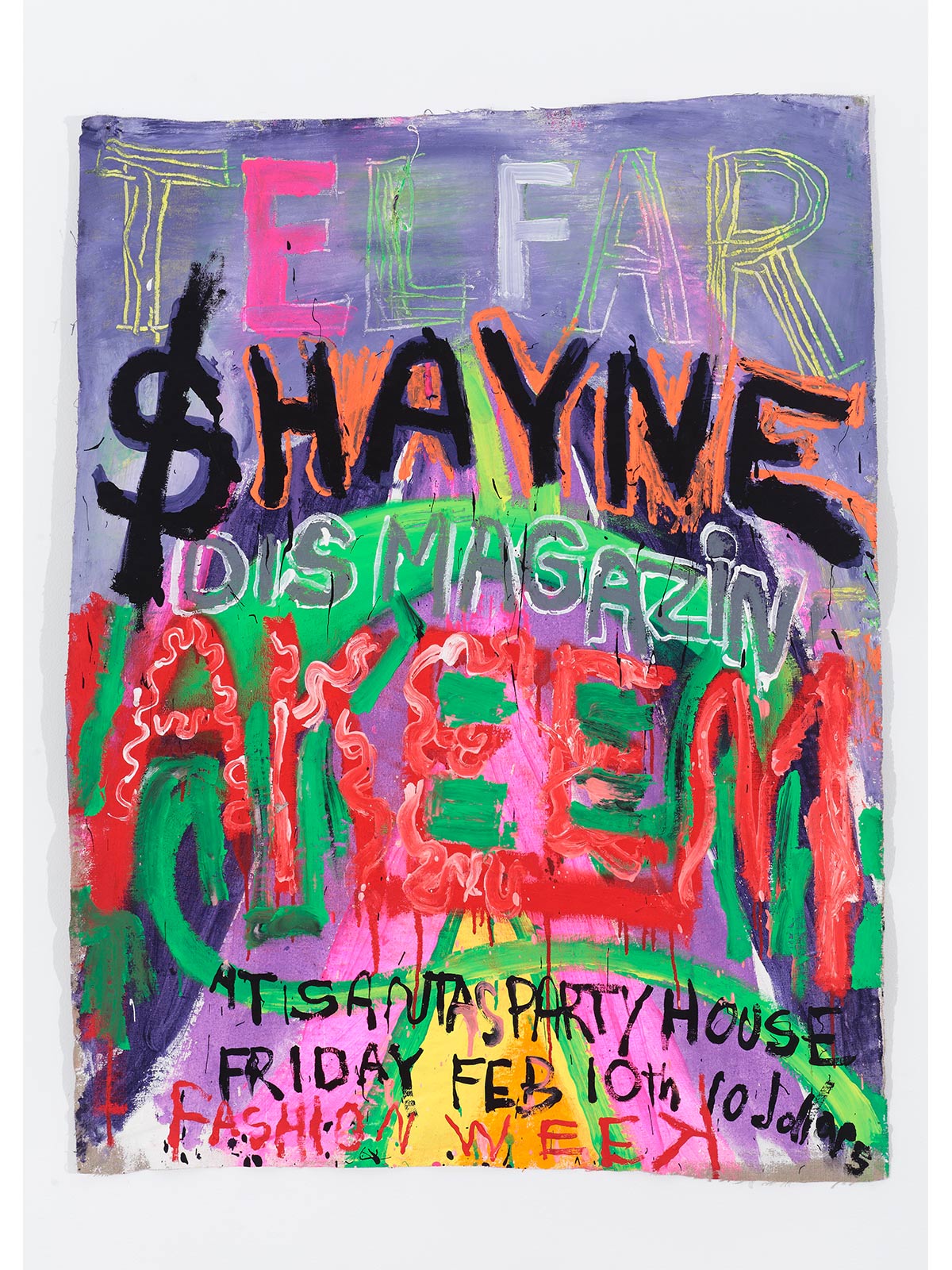

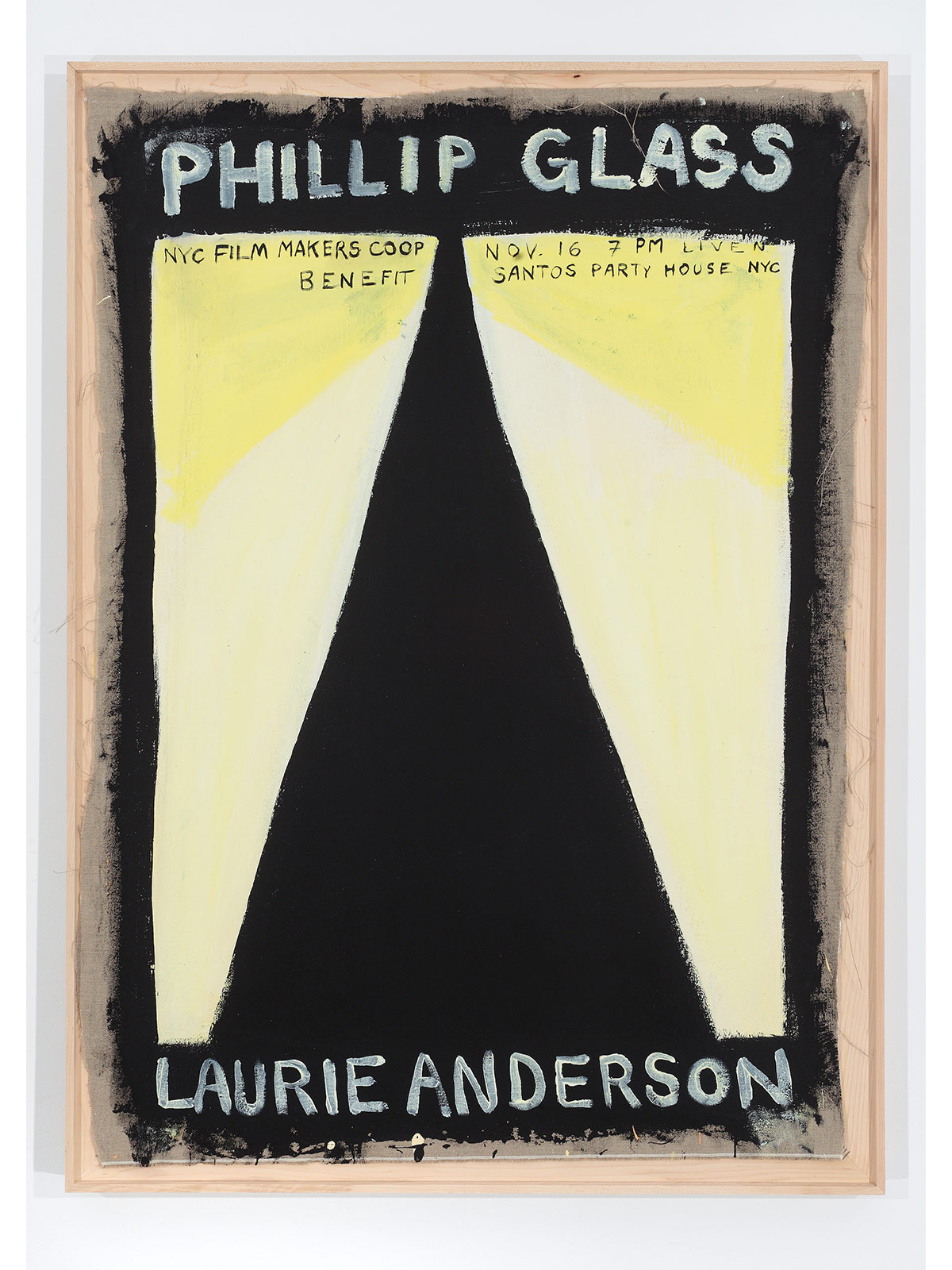

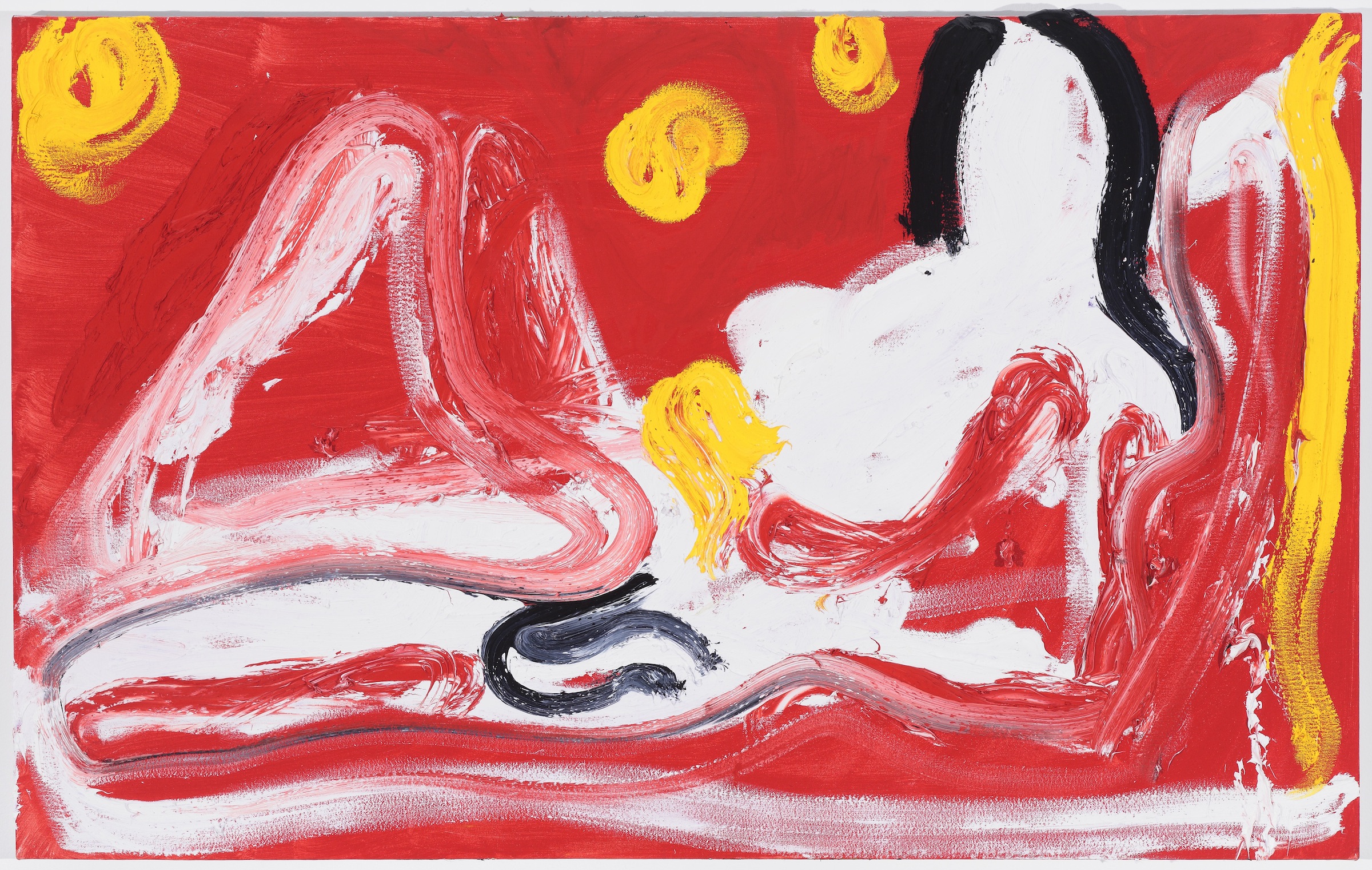

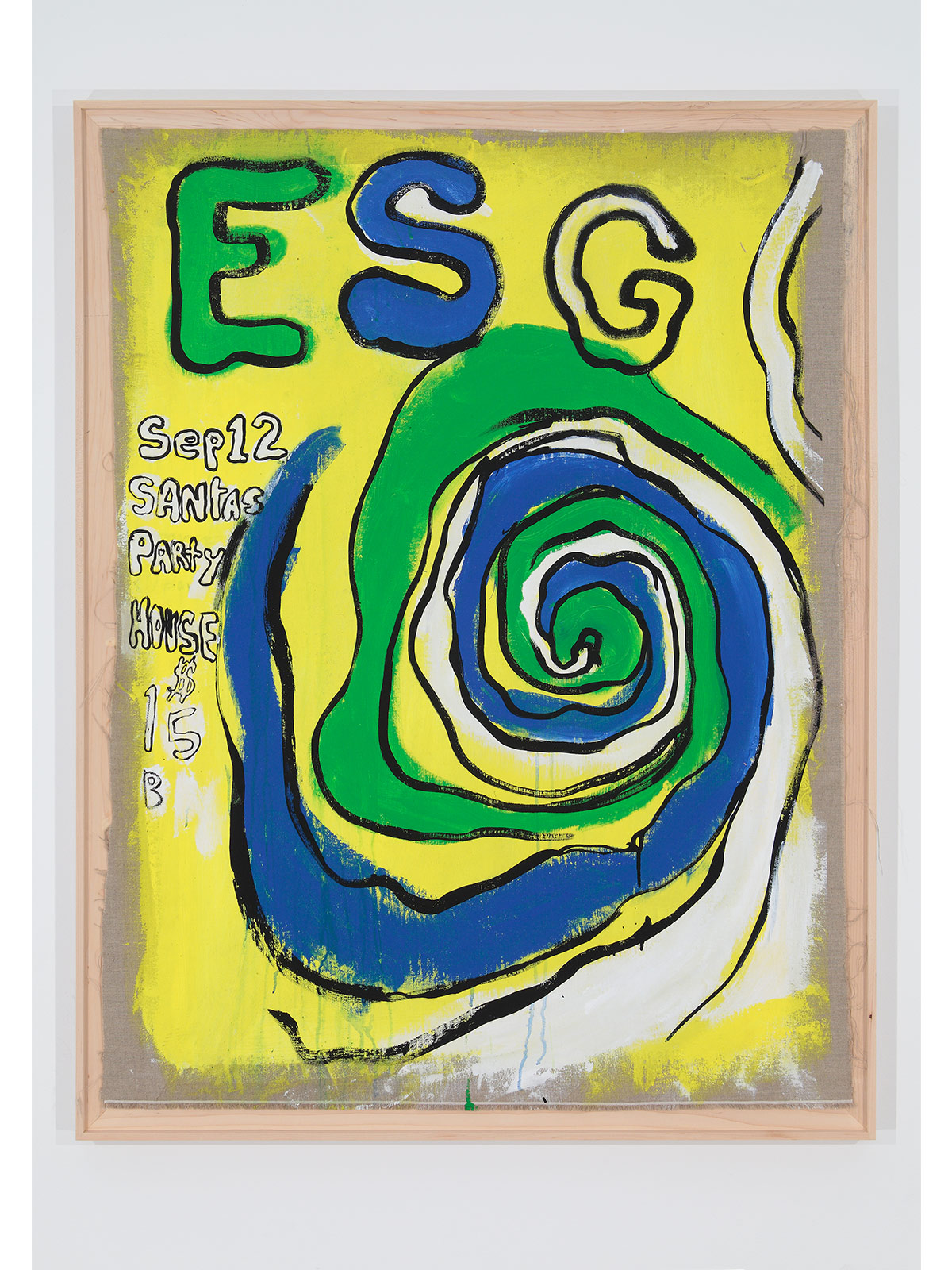

Over the last two decades, Sweeney never stopped making art. He painted abstract self-portraits with bright accents and often feminine attributes. He created immersive experiences, such as moving his studio and living quarters to a gallery for a rock opera exhbit. He performed noise art as a member of the group Actress, and created handmade fliers for his nightclub events.

Most of his work from the last 15 years comes together in Sweeney’s show Perfect, which opened on May 10 at the Brant Foundation Art Study. In this context, perfection is understood in “broad philosophical terms, contemplating the challenges in the full acceptance of life in its entirety including, of course, the imperfect.” The gallery show spans multiple floors, showcasing Sweeney’s self-portraits, large-scale variations of the nude, and collaborative party posters. There’s a scavenger hunt, a heart-shaped disco ball, undefined shapes, chaos—everything that can be characterized as “Spencer Sweeney.”

For Document, the multi-hyphenate artist provides an exclusive look at his iconic party paintings, reminisces about his artistic career, and provides hope for Downtown Manhattan.

Madison Bulnes: You often lean into a humorous and self-deprecating approach to your self-portraits. What’s the reason for that? Would you consider these as more art or documentary?

Spencer Sweeney: Sometimes while making a self-portrait, I’ll decide to focus on the conditions of life that feel less than perfect. This can serve as an entry point to further articulation and fleshing out of the picture. At times, it’s where I’ll find my inroad or groove to follow. There might be a humorous element to that, but it’s often balanced with a measure of pathos. There’s often a good amount of shadow work to be done on a figure whose final expression might seem rather humorous or light-hearted. One still has to face the fear of failure and the unknown; this is inevitably part of the creative process. As to whether it functions as art or documentary, I feel that art oftens functions as a rigorous exploration of aesthetics, as well as a kind of documentary simultaneously.

Madison: What have you learned about your subconscious over the last 15 years?

Spencer: I like to think that every step taken in the outside world, every lesson learned, has a shadow step counterpart in the subconscious. With every expansion of consciousness—maybe through the process of resolving a painting—there is an equal expansion of the subconscious. [It’s] an omnidirectional expansion; two parts of one thing, traveling together and informing one another.

Madison: Fliers from your time at HEADZ and Santos Party House are included in Perfect. What do you miss most about New York’s nightlife and art world scenes during that time?

Spencer: Well, I don’t really miss anything about New York City’s nightlife and art world. What happened has happened; that’s now our history. It’s time to look forward and create. I see nightlife in a city like New York as being a vital and protean kind of organism. If it’s no longer happening in a way that you’ve once experienced, it’s happening somewhere else—but has grown into its own set of circumstances, and will have its unique color and energy. Maybe it’s only a matter of time until you discover the community and activity that will engage your imagination. If you haven’t found it, you can take it upon yourself to create it, or just wait and be patient.

Madison: Do you think Lower Manhattan’s nightlife scene can get back to that sense of community and artistry it had a decade ago?

Spencer: Yes, I do. Obviously, it was knocked back by the pandemic. This was a matter of survival, but we are seeing its return. It can’t happen in the way that it happened a decade before, but [it] will happen with a new color and dimension created by a unique set of circumstances and participants.

Madison: How did you initially approach creating the party paintings?

Spencer: The ideas for the party paintings would usually come about through considering the qualities of the performances or events. There might be specific objects that would illustrate the night perfectly. For instance, for 2 Live Crew on New Year’s Eve, a pink stiletto heel, a bikini, and a gold hoop earring might be appropriate. Other times, a performer will have created such a captivating look that a depiction of them is called for, like in the case of Kembra Pfahler, Omar Souleyman, SION, or Geneva Jacuzzi. For Chris & Cosey or Laurie Anderson and Philip Glass, the gates seem wide open for abstraction. Sometimes, the artist will have such an iconic logo that you can just go with painting that, such as ESG or EPMD. Maybe the artist’s name itself can be a joy to behold—painting the name itself will be the obvious option, case in point ‘JunglePussy and Gobby.’ It becomes a form of automatic poetry.

Madison: Why did you continue making your fliers by hand painting rather than moving towards something digital?

Spencer: There are a number of factors that led me to hand-paint the announcements. They are inspired equal parts by the posters of the late-19th century by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and fliers for punk rock shows by artists like Raymond Pettibon and Pushead. As kids, my brother and I would collect these from light posts and university bulletin boards. I also found it interesting to finish a picture on a deadline to effectively promote the event. [There was] no time to sit around and torture yourself over what to paint. I liked that these paintings had a very specific life and purpose. Another more pragmatic motivation was, at one point, it became necessary to make and sell the announcement paintings to keep the club’s doors open. At this point, it became about the survival of the club and, you know, necessity became the mother of invention.

Madison: HEADZ started when you invited friends to your studio to draw literal heads in late 2017. Why were you drawn into that particular subject?

Spencer: At first, I thought there would be a specific format for the creative work at HEADZ. I decided on the idea of creating these depictions of heads. You know, like portrait-oriented works. But at the same time, the name was also playing on the jazz or hippie terminology of being ‘a head’––being someone deeply interested in something, maybe to the point where it becomes a lifestyle. You could be a music head, a jazz head, a pothead, an anything head—as long as your passion was so strong that you lived by it. Once the party started, the idea of creating the specific heads flew out the window, and the other interpretation of the name became more relevant. [The studio] would be a place for true heads. It didn’t matter what kind of head, as long as you were one.

Madison: Did you imagine HEADZ to become the collaborative mecca it was?

Spencer: We didn’t start HEADZ with any expectations. It was an experiment in bringing the artist’s work out of the studio—a solitary practice into a common space. We bought some art supplies, set up a sound system, and brought some records and books over. I started inviting artists over, and it carried on at a quiet pace for a while. Then the idea to invite musicians to play live, purely improvisational music came about. That was the ingredient that lifted it off the ground. We asked Pete Drungle, a virtuosic piano player, and Craig Harris, a trombone player and composer who worked with Sun Ra and Fela Kuti among many others, to alternate curating bands for each night. The music attracted people exponentially, and we added food and drinks. Eventually, the word got out to local musicians that they could play purely improvisational music to a room full of people painting and drawing. Soon, all of these legendary musicians started turning up to play: Daniel Carter, Wallace Roney, Pheeroan aLlaff, Brice Wassi. It was all word-of-mouth, and the door was open to the public. Promotions through social media were intentionally avoided. Often, people were passing by, [then] heard the music, walked upstairs, sat down and started drawing. This added a consistent element of chance to the attendance. There were all these factors floating around the periphery that were drawn into the studio. What formed was one of those situations where the sum is greater than its parts.

‘Perfect’ is on view at the Brand Foundation Art Study through September 15.