In ‘National Anthem,’ the photographer captures the making of a modern cowboy

It was inevitable that the pop-culturification of the American West would warp its ideals beyond recognition: Shein-made cowboy boots without the workwear endurance to do cowboy things, and pseudo-country stars wearing pseudo-Western styles making pseudo-country music. But despite its mainstream commercialization, there are communities that are truly embodying the heart of cowboy culture, keeping the traditions it was built upon and reappropriating them for contemporary values—arguably, values that have been at the core of its ideologies all along.

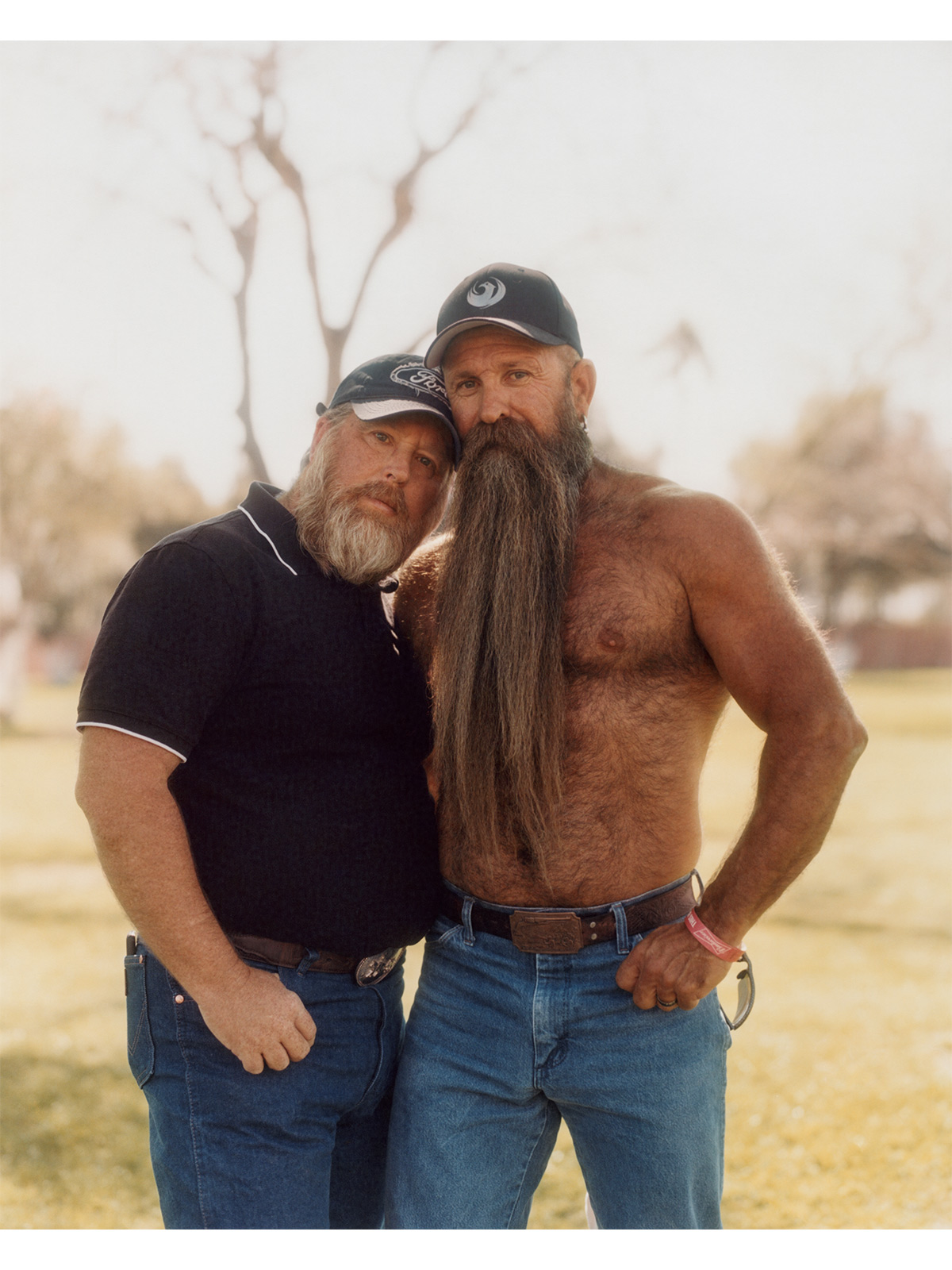

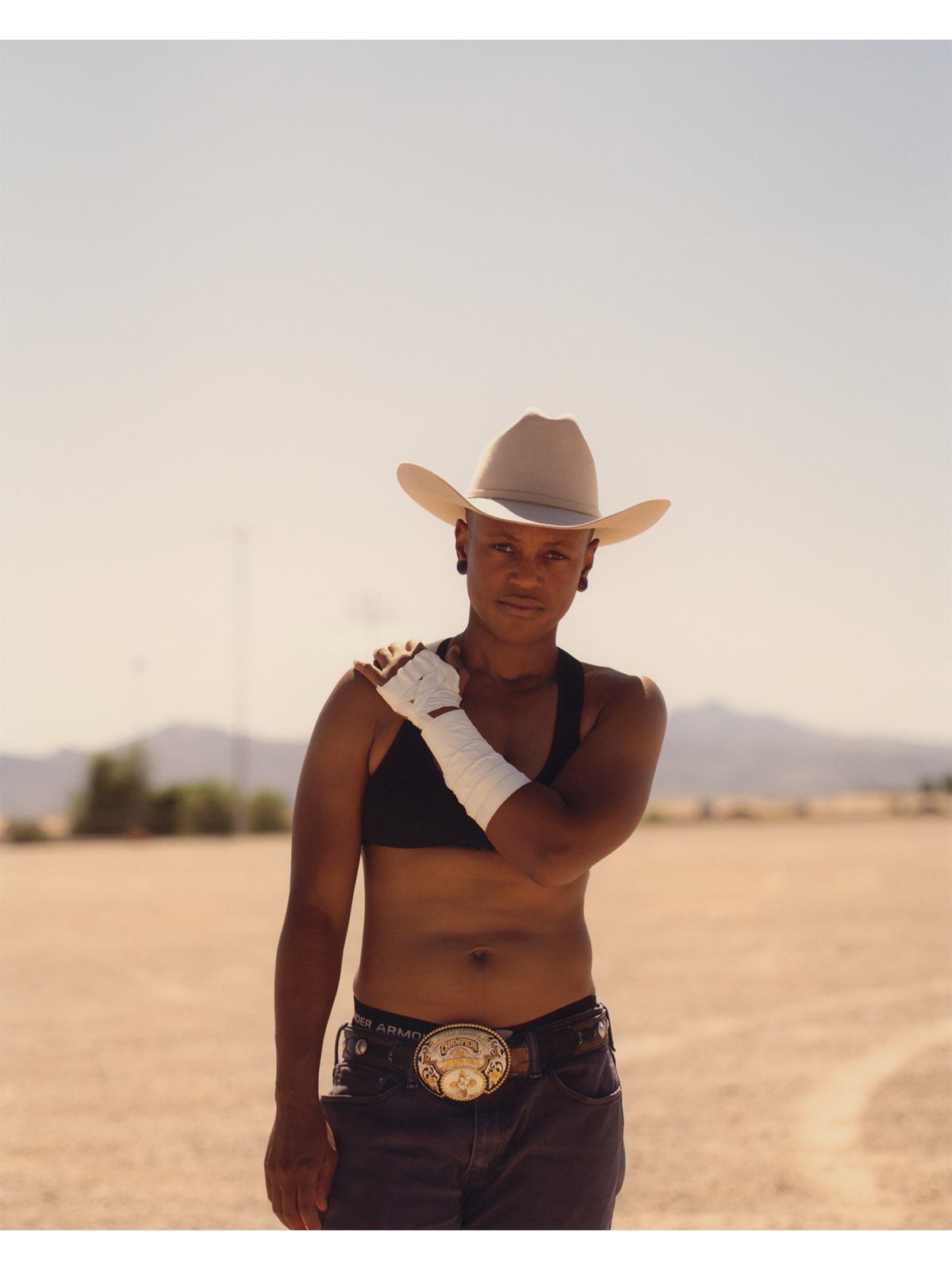

Perhaps the best example of this is the queer rodeo, a community which photographer Luke Gilford has been documenting for the last few years, culminating in a show, National Anthem. His work portraits those left out of mainstream rodeo culture. The idea of the American West began as one rooted in hope and possibility—that anyone could become anything. This concept quickly adopted conditions rooted in racism, homophobia, and misogyny. The queer rodeo erases such conditions, reviving a purity in the values it was supposed built upon.

National Anthem displays the faces of the queer rodeo scene, blown up to massive sizes—an attempt by the artist to remind city-dwellers in particular that these people are real, dressed-up not for costume, but for lifestyle. The individuals Gilford documented embody the valiant myth of the cowboy, without sacrificing other elements of their identities. The images are punctuated by a vertically-oriented video that collages the moments before they were captured, sized to suggest that the subjects are standing in front of their audience.

Gilford joined Document to discuss the making of a modern cowboy and the evolving landscape of rodeo culture.

Megan Hullander: In recent years, especially among younger generations, there’s been a mainstream resurgence of interest in cowboy and rodeo culture. Do you have any speculations as to why that might appeal in contemporary times?

Luke Gilford: America is a sort of mythology that is constantly exceeding and failing [itself]. I think we’re living in a time where it’s painfully apparent that the dream is something we’re all becoming a bit disillusioned by, [but] also realizing that there is still so much more out there than we realize. I think the iconography of Americana is something that will always be resonant to folks.

Pop culture sort of appropriates it, but it often feels very surface to me. That’s what was so exciting about creating this body of work, is that these are real people. Like, this isn’t a costume. These are real, queer cowboys, and that’s actually their lifestyle. It goes beyond the image on the surface. That’s something that I think is really exciting for people to realize, that there are so many other lives out there to lead, outside of the ones that are so popularly represented.

Megan: Are there any elements of rodeo culture that you can pinpoint as a factor to its appeal to queer people specifically, or is there an intersection in the larger communities of queer people and people involved in rodeo culture?

Luke: My dad was part of the mainstream rodeo culture, so I grew up in that world. It wasn’t until pretty late that I discovered the difference, because the mainstream rodeo feels very queer—big hair, chaps, jeans with the bulges and buckles, and skin and sex. Rodeo itself is a sort of pageantry; it is the Western traditional form of drag performance, those sort of hyper-stylized gender roles. I think queer people are drawn to that iconography. But what I love about this world is that it isn’t just the village people re-appropriating that: This is a real community that is typically excluded from that white, Christian, misogynist world. And they are turning that on its head and saying, No, I do belong here like this. These are my symbols, too. I can also ride a horse, ride a bull. And there are women and trans people getting on bulls, which has never happened in rodeo. There are all kinds of people of color—Native American, Latino, Black people. People who are not welcome in the mainstream rodeo.

That’s something that I’ve really come to appreciate about this rodeo, too. It’s not just for queer people, it’s for anyone who’s been excluded from the American Dream. It’s something we can take for granted in cities. But outside of cities, in these rural places, it can still be very much segregated or casually racist.

Megan: As someone who has lived in rural spaces and in major cities, what do you see as the most prevalent misconceptions about the rodeo scene coming from the coast, or even just around rural communities?

Luke: A lot of folks, unfortunately, think that the rodeo is abusive to animals. The queer rodeo is different. These people are saving animals from slaughter or from really abusive situations, and taking care of them. So many queer people are caretakers. And it’s a super family-friendly environment. In urban places, queer spaces are often centered around drugs. And the rodeo is not necessarily that way. A lot of these people have children. It’s super wholesome.

And for rural places, there are so many people who defy the stereotypes, who are very much liberal and progressive in the South. Unfortunately, even parts of New York are extremely conservative. Or Beverly Hills is an area that’s very conservative, but people don’t think of LA as that. There are people who have different beliefs in different areas. One thing that is fascinating as a statistic, is that there are actually more queer people outside of cities than in cities now.

Megan: I feel like that misconception stems from the idea that a lot of Middle America is more rooted in tradition. And there are a lot of traditions within it that are perceived as archaic, but do you see any elements of those traditions that are actually progressive?

Luke: To me, it’s simply the tradition of a group of people getting together in the great outdoors with animals, building community in nature with families. Even just the tradition of singing the national anthem is very cringe for a lot of people in cities. But I think it’s so beautiful to see a bunch of queer people and people of color gathering and singing the national anthem—something that typically excludes them—re-appropriating the land of the free and the home of the brave. There’s so much haunting beauty to that. I think it’s about taking traditions and repurposing them for our own meaning—that’s what people need to feel like part of this country.

Megan: How would you describe the personality of the rodeo?

Luke: The first word that comes to mind is warm. The people are so warm and loving and tender. And it’s non-judgmental, [which is] really refreshing, especially coming from places where it’s so much about your status and follower count. Like, What can you do for me? How much money do you make? What do you look like? How much do you weigh? None of that is a factor [at the rodeo]. And that’s what kept bringing me back, it’s something that I hadn’t experienced anywhere else.

Megan: How do you think that being someone who was already sort of integrated into those communities served you artistically?

Luke: I felt excluded by that Western culture, because as I got older, I came to realize that this place isn’t for me. [I realized] that the rodeo clowns I grew up loving were sort of mocking queer people. There are so many things about that world that are super sick. So then, discovering that there’s a place for people like me who grew up around Western culture, or just appreciate it and want to be part of that world… There are many folks moving out of cities and going to Texas. There’s a mass exodus happening from LA and New York. There are also people who just want to be part of a community. For me, it was like the shining beacon of light against the stereotypes that we’re taught through pop culture. Any rural queer story I’ve seen is represented as a tragedy: Brokeback Mountain, Boys Don’t Cry. [But the queer rodeo] is a celebration. It’s bliss. I had never seen something like it before.

Megan: I imagine you had a massive archive to pull from, so how did you go about selecting works for this exhibition? And what were you hoping to say with your selections?

Luke: I really wanted to print this at a pretty large scale—for people to feel the nuances and see every pore and hair and detail in their eyes. To be confronted with these people as real, living, breathing heroes. And for different technical reasons, some images hold up better than others. That was part of the process, to make sure that everything worked well together and told the story and that there were different types of people represented. I also really wanted to play with diptychs and triptychs. There’s a triptych of people with injuries to remind folks that it really is a dangerous sport, but it also points to their resilience.

Megan: Can you tell me about the function of the video in the exhibition?

Luke: That’s actually my favorite piece in the exhibition. I really want people to see it in person, because it’s vertical, and also so big, so it’s as if these people are standing in front of you. I think people can sometimes forget, and also just in New York City—like, we see so much imagery that is hair and makeup and costume. But this is a hopefully poetic reminder that these are real people, real places. This is documentary. I think that, for a lot of people, that’s been really impactful

Megan: You mentioned that a lot of these people you’re shooting aren’t used to being photographed in this way. What have the reactions been like when you show them the end product?

Luke: A lot of these folks aren’t on social media, or don’t even have smartphones. It was years of me going to these rodeos, taking photos, and making friends. They just thought I was some random guy. I don’t think anyone expected it to culminate in this way. Now they all feel famous. There’s one person named Tessa who’s a trans woman, and it’s not really safe for her to live as a woman, but she comes to the rodeos as a woman. For her to see herself, she broke down in tears—it was the first time she’d seen herself represented. She actually has cancer, so she was so thrilled that she could see herself represented that way before she dies. That was a huge moment for me, to take that in and realize that this is much bigger than me. This is meaningful for people on a level that we take for granted oftentimes—because of social media, or just how much representation is out there. But for some people, it’s life.

National Anthem is on display at SN37 Gallery from July 14 to August 28.