Laurie Simmons and Drew Sawyer discuss the late artist’s AIDS-era collages in a portfolio for Document’s tenth anniversary

Set in the middle-class, suburban landscape of Atlanta, adjacent to overstuffed sofas and coil-cord telephones, Jimmy DeSana’s first mature work, 101 Nudes, cast the artist and his friends disrobed, some gazing directly into the camera’s lens, posed stiffly like Ken dolls (but with distinctly normal bodies and bouffant hair), and others shown only in pieces or plunging face-first into cushions like porn stars. Placing the naked body—unedited, unwaxed, and unsculpted—in the hypertypical American home was revolutionary then for its unerotic gaze, and perhaps is even more revolutionary now, in the age of preventative Botox and Photoshop filters. The Detroit-born photographer’s work confronted conversations of acceptability with their expansive approach to gender and sexuality in ways that even today, decades after their creation, distort institutional boundaries.

A deviant of postwar suburbia’s nine-to-five generation, DeSana was a fixture of the New York avant-garde scene in the 1970s and ’80s, living and working amongst like-minded iconoclasts whose digressions would decades later become textbook norms: Kathy Acker’s experimentations in writing on trauma, Brian Eno’s conceptual approaches to ‘nonmusician’ music, William S. Burroughs’s self-reflexivity, and Kenneth Anger’s merging of surrealism and homoerotica in film. DeSana’s anti-art is conceivably the most undercredited of the East Village punk and New Wave scene that set a base for the values of contemporary culture.

DeSana didn’t quite fit into the queer art boom of the time, which mostly catered to the gay liberation aesthetic—works like the portraits of Peter Hujar are effective reflections of the edges of culture, applying classical photographic language to people not usually captured in that way. But within this context, DeSana’s work feels idiosyncratic and not necessarily tied to any one particular moment. Rooted more heavily in concept than in documentary, his images refracted reality by decontextualizing the body. In resisting the dominant modes of his contemporaries, he didn’t mold queerness into a heteronormative reality, instead creating worlds that were simultaneously mundane and bizarre.

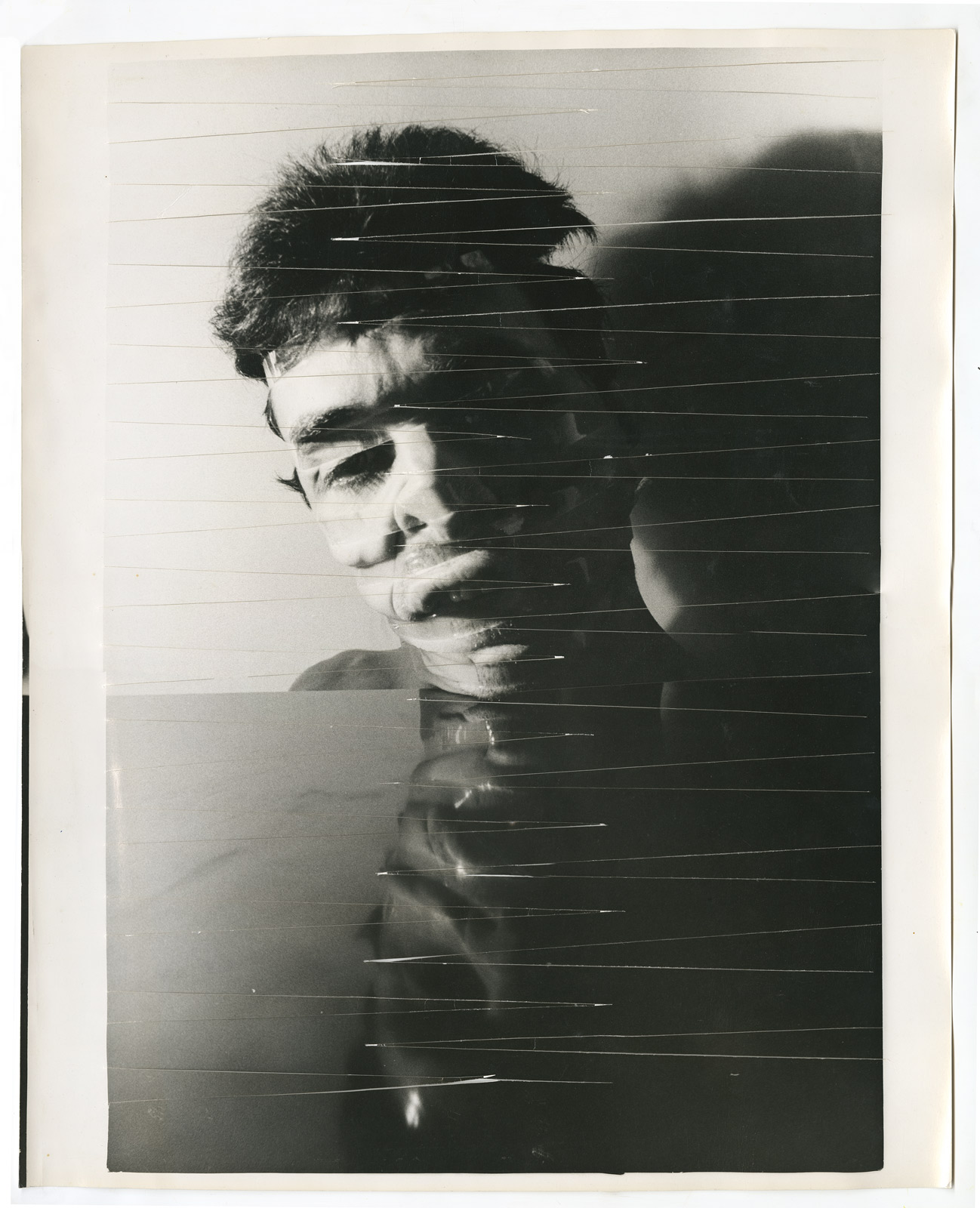

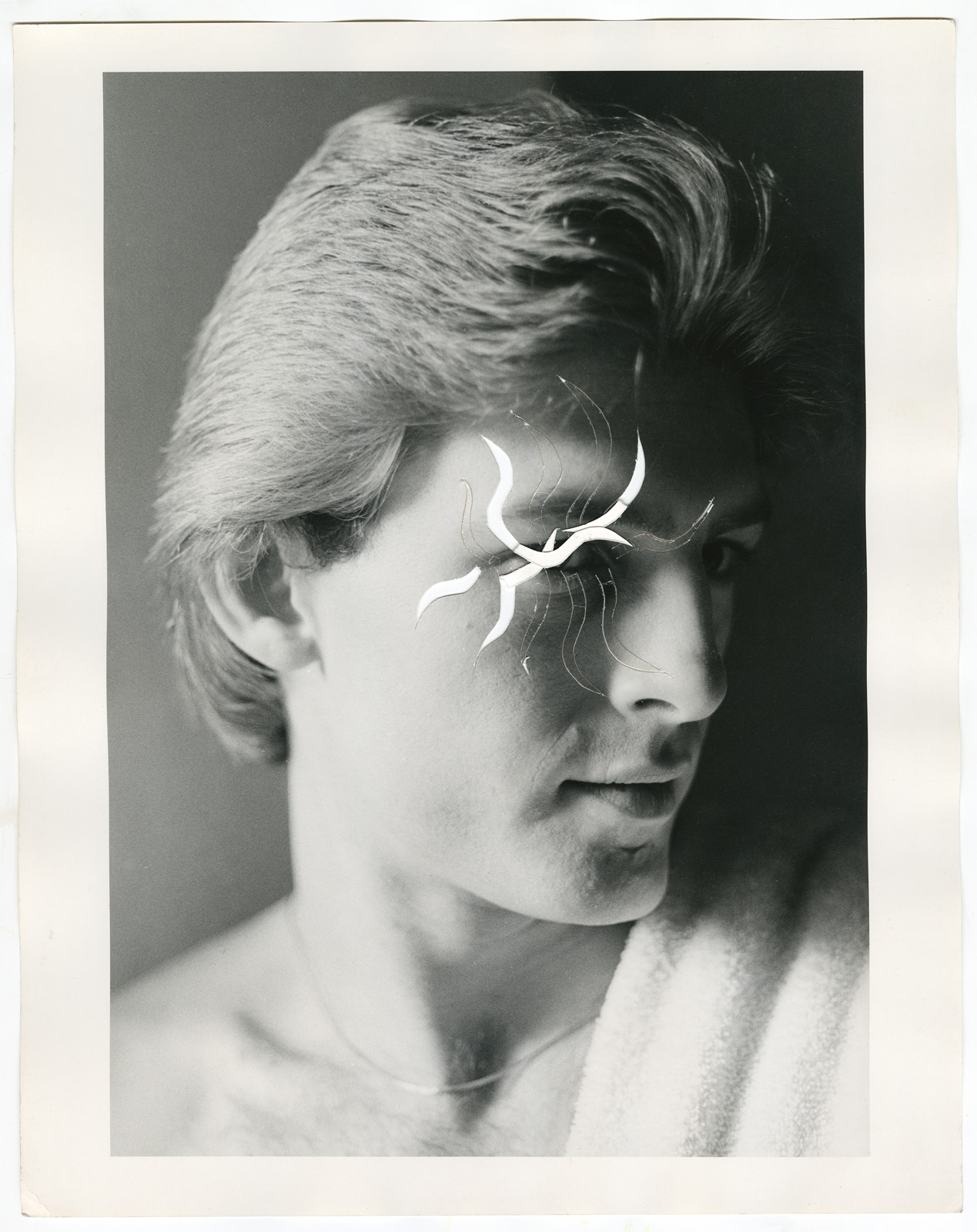

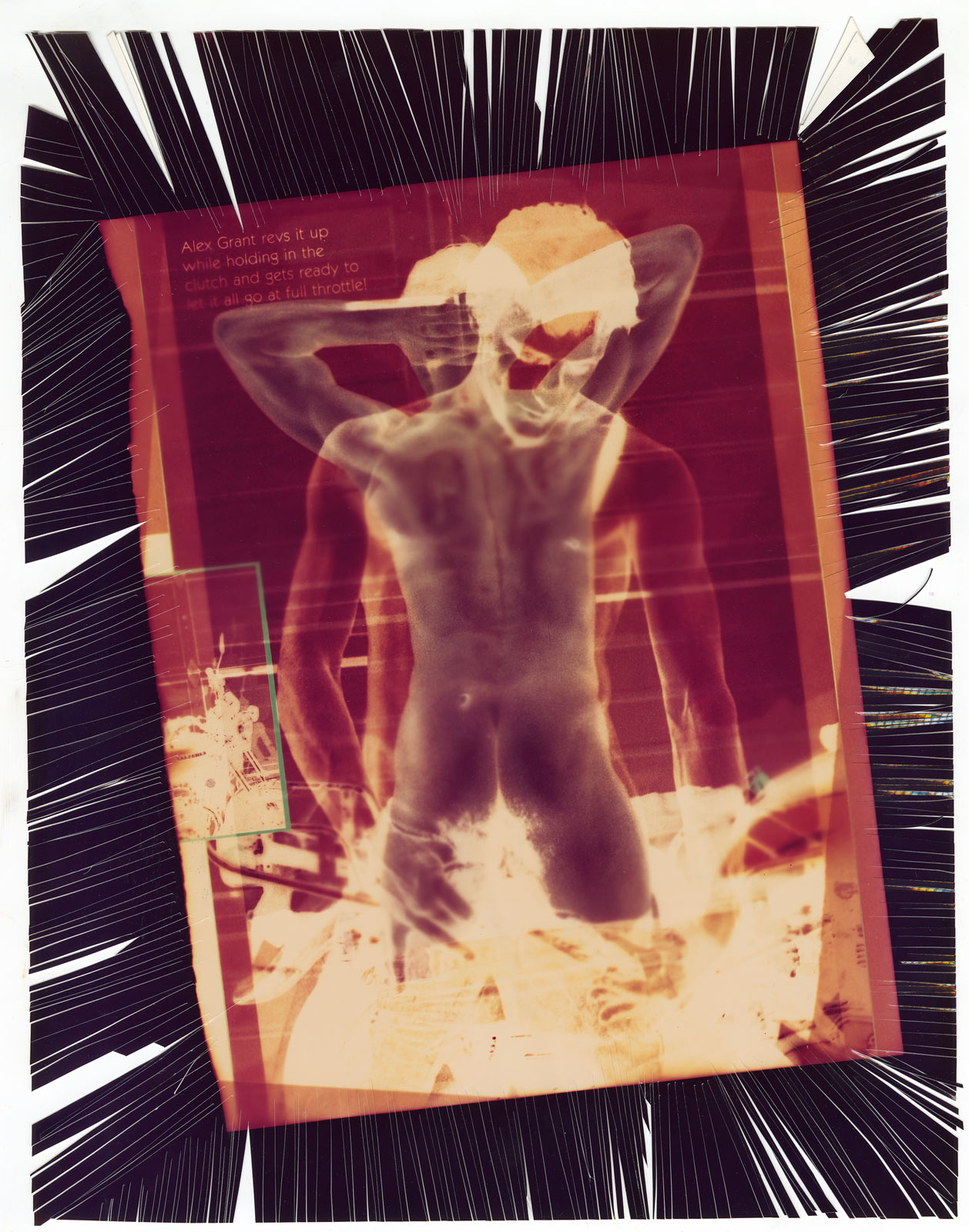

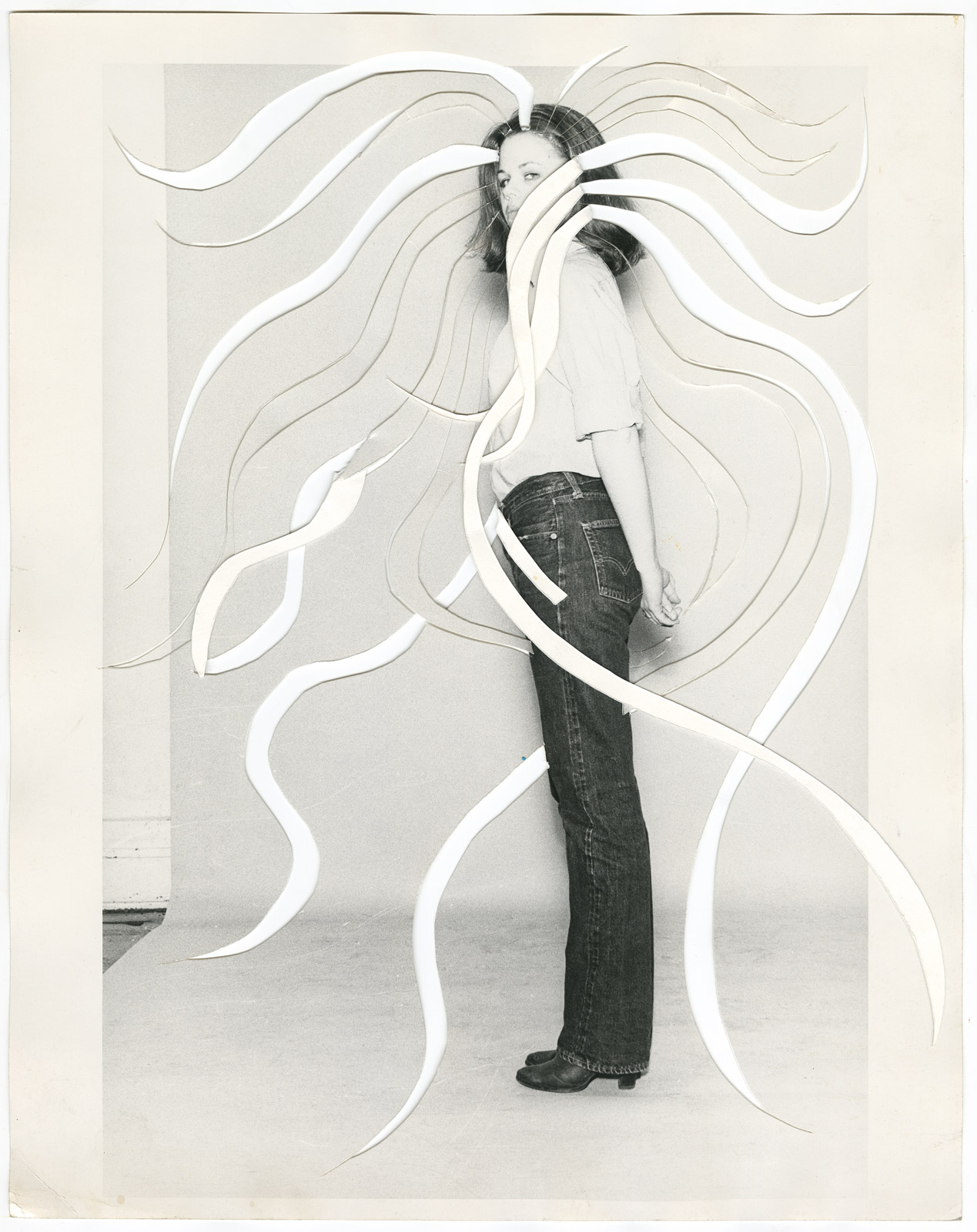

That uncanny language was shared with Laurie Simmons, known for her staged domestic scenes using dolls and miniature objects that, like the works of DeSana, surrealized suburbia. The two shared a studio until DeSana’s death from AIDS-related illness in 1990. Simmons watched her friend transform after his diagnosis, a change that manifested as both physical degeneration and artistic metamorphosis. “We didn’t want to be painters. We didn’t want to be sculptors,” Simmons recalls. “We wanted that sense of distance and remove. We wanted a tool that we could work with, but that didn’t have anything to do with craft.” Illness forced DeSana to put his camera down and collage. Struggling to make sense of the purpose of the body, and especially the sexualized body, amid a vicious disease that mostly took queer, sexually active bodies like his own, DeSana made sense of his world through chopping and repasting it. The distance and remove that he and Simmons craved, that the camera gave him, was impossible as the reality of death loomed so near.

At last receiving his institutional dues, a DeSana retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum opens November 2022 and will be followed by an exhibition at PPOW this winter.

The two foremost experts on DeSana, his closest friend Laurie Simmons and the art historian Drew Sawyer, meet to discuss the enduring value of the artist’s work, the impossibility of shock in the age of the internet, and the persistent fight to commodify sex.

Megan Hullander: How’d you meet Jimmy DeSana?

Laurie Simmons: We met on the A train for Rockaway, with a whole group of people that was going out to the beach. Jimmy was all dressed in white—a white Panama hat, white clothes, a spray-painted Yashica GT35 around his neck, and a very thin rhinestone necklace. Actually, he wasn’t very costumey. He was preppy or collegiate, the way he dressed. It was always khaki pants and a white shirt. Very plain. So that little affectation of the rhinestone necklace was pretty unusual. I mean, you’ve never seen any photos of him, Drew, where he was dressed up in anything crazy?

Drew Sawyer: With the help of Ray Johnson after he moved to New York, he collected thousands of hats.

Laurie: He said thousands, but he was so prone to exaggeration. I would say hundreds.

Drew: He claimed 15,000.

Laurie: That is so not true!

Drew: I remember one of the things that Robert Stefanotti, who was a dealer in the ’70s in New York and became Jimmy’s boyfriend around 1974, remembers was black fingernail polish.

Laurie: That sort of rings a bell, but honestly, we were all wearing weird fingernail polish. Even now, I’m in England at my daughter’s house, and her husband’s a musician—he’s wearing chartreuse nail polish. Straight guy musician, but it’s not the kind of thing that one would even register.

Megan: It’s strange that nail polish and jewelry still exist as small acts of subversion against the norms of masculinity. When you look at DeSana’s work, even now, decades after its creation, its thematics and the conversations it addressed seem ahead of its time, and our time. What do you feel is relevant about his work today that might be different from the way that it resonated when it was made?

Laurie: Just the fact that Jimmy was working in color—when we first came to New York, Mapplethorpe was working in black-and-white, Helen Levitt was working in black-and-white. In 1976, when the [William] Eggleston show happened at MoMA, everyone was making such a big deal about the fact that it was the first color show by a photographer, and we were like, Give me a break. We didn’t feel like a museum show of color photographs felt that radical.

Drew: I think of both of your early color work, and how different it is from the color work that was being accepted. The little amount of color work, like Eggleston, that was being accepted within art museums and galleries, all tended to use naturalism.

Laurie: It was street photography in color.

“Collage took him to a very intimate, hands-on way of working that’s so much more personal. Yet by rephotographing the collages, he could keep that sense of distance and still see himself as a conceptual artist, which I think was part of how he needed to see himself.”

Megan: How do you feel your work was feeding off of each other’s, maybe ideologically?

Laurie: I very much identified as an artist, and he very much identified as a photographer. I decided to pick up a camera as an artist. Fortunately, my friend could teach me everything I needed to know. He taught me how to be a photographer, and I taught him how to identify as an artist. It’s not that our imagery was so connected—I mean, certainly our investigation of suburban culture was connected. But it was more that our sense of who we were in the world as artists merged.

In fact, the biggest art fight that we ever had was when he made a scanograph where he took a photo and had it printed on a huge canvas. Now, I think that was absolutely visionary. But I was so furious at him. I thought he was such a sellout. I said, ‘You’re doing that because you want to make money and you wish you were making paintings, and you’re abandoning photography.’ But he was embracing a new technology. After that, people were having, like, a Monet printed on a canvas and hanging it—people with great wealth were trying to find ways to put art in their house that was somewhere between having an Old Master and having a photograph. So the thing that I got the angriest at him for is something that I now think was pretty radical.

Megan: On the subject of new mediums, I read that he didn’t start collaging until later in his life. What do you think it was about it that attracted him at that time?

Laurie: I see everything as before and after the diagnosis. After the AIDS diagnosis, everything changed. I would attribute the change to a spiritual alternative mind—an anxiety about dying, a curiosity about dying, the abstract nature of not knowing what lies ahead of you. Everything just changed. I was confused by it all, but accepting. It was just like, ‘You’re an artist. If that’s what you’re doing now, that’s what you’re doing now.’ But it was a pretty radical change. I could only interpret it on a more psychoanalytic or spiritual level, just suddenly not knowing what lay ahead, and also the fact that he had to watch so many people around him die. I lived through it, so I had to steel myself against it at the time, but right now, I don’t know how any of us lived through it. You just didn’t know who was going to die next.

Drew: Up until that point, he had mostly been making work that in some way engages with sexuality and the body. I think a lot of artists were [asking themselves], with the AIDS epidemic, How do you think about those things in the same way? Especially in a political climate that became so polarized. There was an intense conservative reaction to homosexuality, which became increasingly more visible during the AIDS epidemic. Like, what are forms of representation that allow you to still address the same things you want to? I think Jimmy was inserting a particular subjectivity into these other modernist modes of making.

Laurie: Jimmy had an enormous curiosity about the afterlife that we would talk about sometimes, but in very abstract ways. I feel like there’s a kind of cloudy, misty, not-quite-there quality, or just this idea of this interstitial space between life and death. And more and more, when I look at the abstract pictures, I feel like there was some rumination about what lay ahead, what you might see when the end is there, and you go through the tunnel, and you see people far away or whatever ideas we have about the afterlife. Forget about Submission, even Suburban, they were so about real life—and suddenly, he was often away in this other world.

The thing that drew us to using a camera was [that] we didn’t want to use our hands. We didn’t want to be painters. We didn’t want to be sculptors. We wanted that sense of distance and remove. We wanted a tool that we could work with, but that didn’t have anything to do with craft. Collage took him to a very intimate, hands-on way of working that’s so much more personal. Yet by rephotographing the collages, he could keep that sense of distance and still see himself as a conceptual artist, which I think was part of how he needed to see himself.

And he became weaker. Going out with your camera, finding things to shoot, being out all night, that was not his life anymore. The craft part of the collage just filled time in a certain way. [He did] everything he could do to fill up time with his work—apart from organizing it, which was left to me!

Drew: I also just think it’s a different context and all of these artists are also drawing on the legacies of modernism in different ways. And imbuing them with a sort of subjectivity in different ways.

Laurie: It’s so true!

Drew: A lot of people will say, ‘East Village photographer Jimmy DeSana.’ He never lived on the Lower East Side or in the East Village. He participated in that scene in various ways, but he never lived in that area. It’s hard to fit Jimmy into these strict narratives that we’ve constructed or honed around contemporary art, especially during that period in New York City. I think, of course, Jimmy was not alone. So many of these artists moved freely between all of these spheres, but they become historicized in a way. They’ve become codified and lost some of this nuance.

But his turn to collage does coincide with showing with Pat Hearn. And even his big work, I have to imagine that producing that scale of work, the 40-by-50 superchrome prints, wouldn’t have been possible if he hadn’t had the support of a gallery like that.

Laurie: He was an amazing chameleon. He could really absorb what was going on around him and it would come out in the work—like, what he saw in other artists, movies, music, whatever. I felt like he was channeling constantly.

Megan: How do you think the suburban upbringings that your works addressed influenced his and your experience in the city and how did that translate into your work?

Laurie: We both understood that it was such a great journey for both of us from where we grew up to where we were. A lot of kids go to art school now and become artists, because they think there’s a possibility to make a living. There was no possibility to make a living [then] that all started in the ’80s. There were a number of artists that were mining their pasts, which is happening again. It’s happening with a lot of young artists, particularly artists of color, who are very keen to or anxious to revisit their past as a way to explain who they are, where they are now.

It’s often discussed that we were the first generation to be totally raised on television, which doesn’t seem like any big deal to you guys, but there was a time when there was no television and then there was television. No parents had any idea that putting their kids in front of this box was a negative. We were very aware that we were raised by this electronic babysitter. It will be the same thing for the generations completely born into the digital world.

Drew: But there was not a huge variety [on TV]. The constructiveness of what America meant through television was so much more limited than it is today. Now, you have access to so many different people producing different stories from different perspectives. Which just didn’t exist then. The way I see your work and Jimmy’s work is mining this idea of suburbia that existed for years as children, as teenagers. That was totally fabricated, right?

Laurie: Absolutely! It wasn’t real life! Real life wasn’t Father Knows Best and The Donna Reed Show. Everything in post-World War II America was whitewashed—which is a word I’ve always used, which means so much more to me now than it did when I started using it in the early ’80s or late ’70s. There was a kind of perfection that had to exist in postwar America that was on TV.

On the other hand, if you watched some of the shows that we watched, the children’s shows, you’d be terrified. Some of the characters on TV when we were little, like Pinky Lee, make Pee-wee Herman look tame. Before TV, you could only see a ventriloquist dummy at a birthday party once or twice a year. By the time I was a little kid, you could see that every Saturday and Sunday.

“Maybe the art world is no longer a place for the avant-garde?”

Megan: Well, part of what made that generation of work you were a part of so impactful was its deviation from that limited media. Do you think New York is still a breeding ground for counterculture? Or is that lost with the saturation of media?

Drew: I think, especially in the ’70s, so much of it was about world-making. I think about it in terms of your work, Laurie, and Jimmy’s, and so many other artists’—this moment of both identifying but disidentifying with culture, as it had been portrayed or as you had consumed it. And in New York, finding a way to make your own culture, finding ways to make work that was separate from existing institutions. Part of that was by necessity because those existing institutions weren’t interested in showing your work.

Laurie: But they weren’t cool either!

Drew: Right! I think of the ’70s as such an important time in terms of world-making, especially as the art world exists today. It was a decade of intense institution-building, network-building, all those things that really impacted the way that contemporary art functions.

Laurie: It’s making me think about, what would you have to do to be subversive or avant-garde today? It was so easy then, there were so many paths to that. My father would just lecture me and say, ‘You want to be an artist—you’re not going to get married, you’re going to live in a cold-water walk-up flat.’ What’s a cold-water flat? [Laughs] He was so frightened for me and what my life would be like if I chose this path. It was so easy to defy your parents, and defy your upbringing, and go to a big city. It was so easy to be avant-garde, it was so easy to be radical. I’m saying that from my point of view now, when 99 percent of the people in my high school did not choose that path. But what would one have to do now to follow that path?

Sometimes I think, Would I still be an artist now? What would I be? Sometimes I think I would be a girl gamer, because where would a fierce girl go who wanted to constantly be in conflict?

Drew: Maybe the art world is no longer a place for the avant-garde?

Laurie: Yeah!

Drew: Actually, it’s somewhere else. Us in the art world, we don’t know where that is.

Laurie: We don’t know! My kids love it when I say I would be a gamer. They say, ‘Mom, do you mean you would make games? Or, like, what?’ But where is that space that’s comparable to how we felt? Maybe I’m being naïve. Maybe every young new artist who comes to New York feels the way I felt or Jimmy felt, like they’re so far away from the way they were raised. It’s interesting how much more difficult it is to shock people. Maybe shocking people isn’t even the idea or the goal, maybe that’s not even part of the vocabulary.

Drew: In the ’70s especially, it was obviously about transgression, the history of the avant-garde has been a history of transgressing. Now, there’s so much more emphasis on different effective modes of what art can be. Whether or not that’s the very opposite, which is making sure it’s a safe space [where] one can really care for one another, it’s very different from a space of transgression.

Laurie: The things that my kids say, like, ‘I hold a space for you,’ and, ‘This is a safe space’—it’s just like, No! Stop it! Also, by the way, we’re in the middle of this incredible sexual revolution. What we did might seem absolutely tame today. I know what goes on, I read things, I have children. But that really turned our world upside-down and really upset the generation before us.

Megan: When you look at a platform like OnlyFans, and the controversy that’s been generated around that because of the societal discomfort with sex as anything but private and free, it’s commodifying sex in the same way art maybe did at that time.

Drew: Even thinking about [Jimmy’s] collaboration with Terence Sellers, who was a sex worker and writer: He photo-graphed her, and practiced S&M to some degree, and did the Submission series. But Sellers is far lesser-known today. I think that’s partially because she was a sex worker. There was a degree to which others pulled from and incorporated sex into their work, but it was another thing to be a practicing sex worker, [in terms of] the prospects of you being taken seriously.

Laurie: One of the things that separates Jimmy from other artists is his upbringing. He was a Southern boy, he really wanted to shock people. The ways that he did it personally, like the little necklace or the black nail polish, were small gestures. But I think in his internal competition with, for instance, Mapplethorpe—he wanted to be more shocking than Mapplethorpe, and he wanted to believe that Mapplethorpe’s approach was perhaps too tame and too aesthetic. I don’t know if that’s a way of thinking or being of the young people we know in the art world—I don’t know if that’s an operative now.

Drew: It doesn’t seem like it to me. We take it for granted today that things are not shocking. It’s the battles that people like Jimmy and others had to fight to be shocking. And we can sit back and take it for granted that this thing exists and doesn’t shock anybody.

Laurie: The things that shock me now are the things that are being written about all the time, like the epidemic of loneliness, the incredibly high rate of teen suicide, and the effects that a shocking world has had upon subsequent generations. The oldest structures that are broken down, that were part of what we were rebelling against, are not there for support. I’m talking about families, religion, and schools—all of the constraints we had to push against are not that powerful anymore. People are adrift.