The photographer joins Document to discuss their first monograph, using props to stretch their artistic vocabulary, and the importance of documenting joy

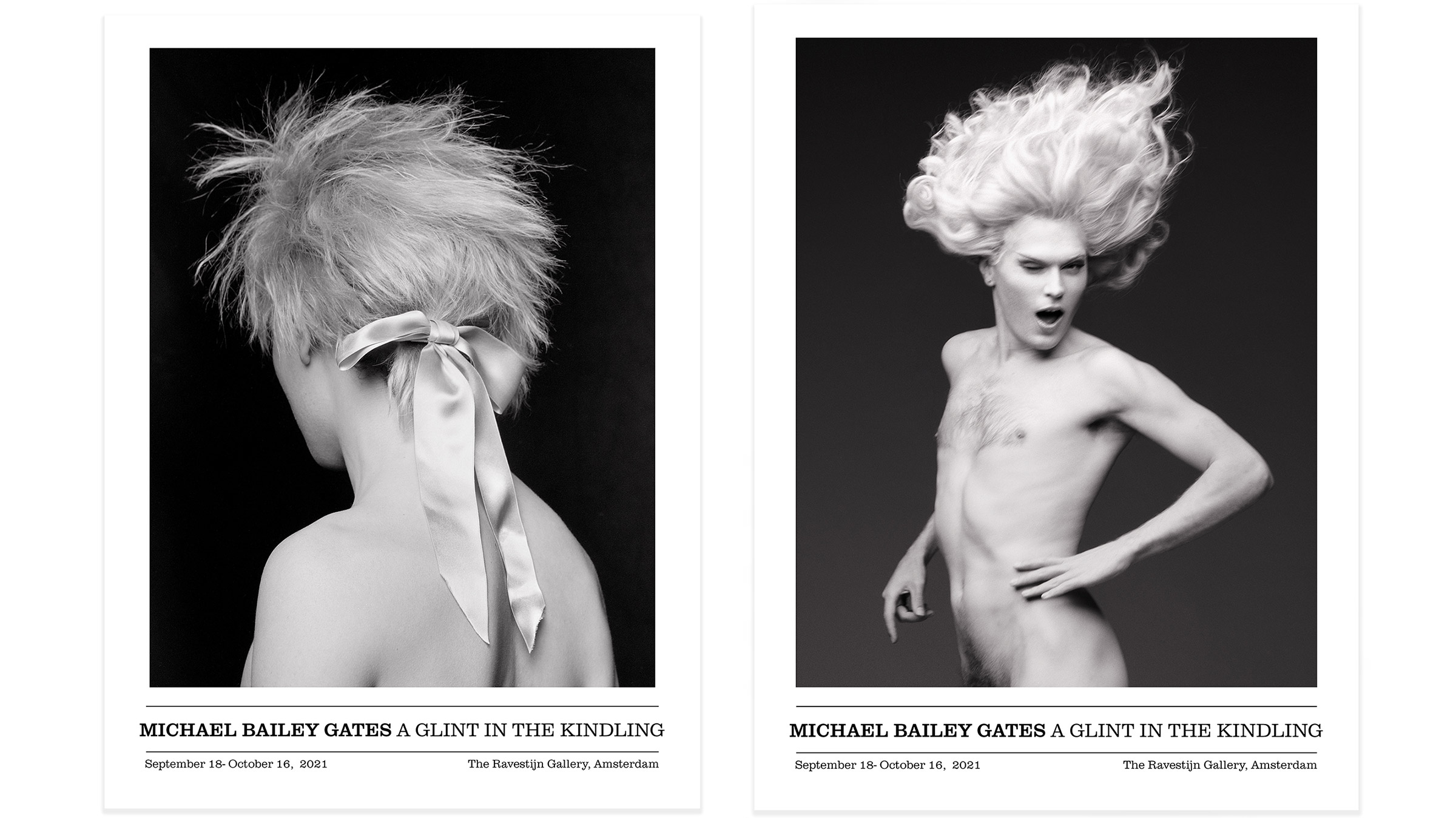

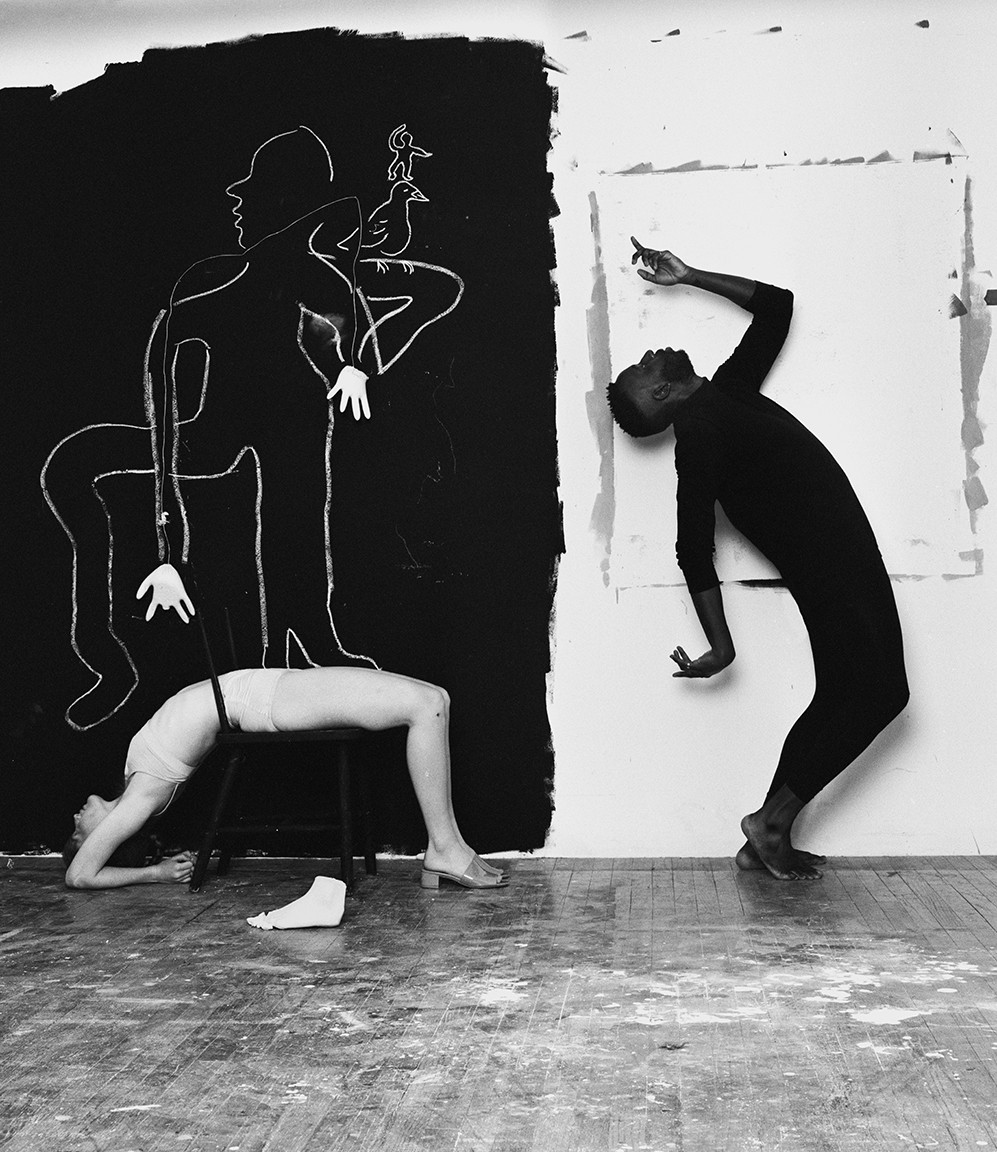

Michael Bailey-Gates’s first monograph, A Glint in The Kindling, leverages artifice to create a world where imitation and reality become indecipherable. In this world, minimalism and excess exist in harmony to form their inimitable aesthetic. Gates inserts themself into their portraits, becoming a subject alongside those they photograph. In turn, their work takes on the spirit of a collaborative theatrical production. The photographer breaks the fourth wall—exposing backdrops, shutter release cables, and the camera itself to construct scenes that endow their subjects with power and poise. In one image, two figures lie down, one beneath the other on wooden platforms, holding candles to their foreheads in unison, peering at the viewer as if in invitation to join in on their covert ritual. In this way, Gates’s work lets us in on a secret, and leaves us wanting to know the nature behind it.

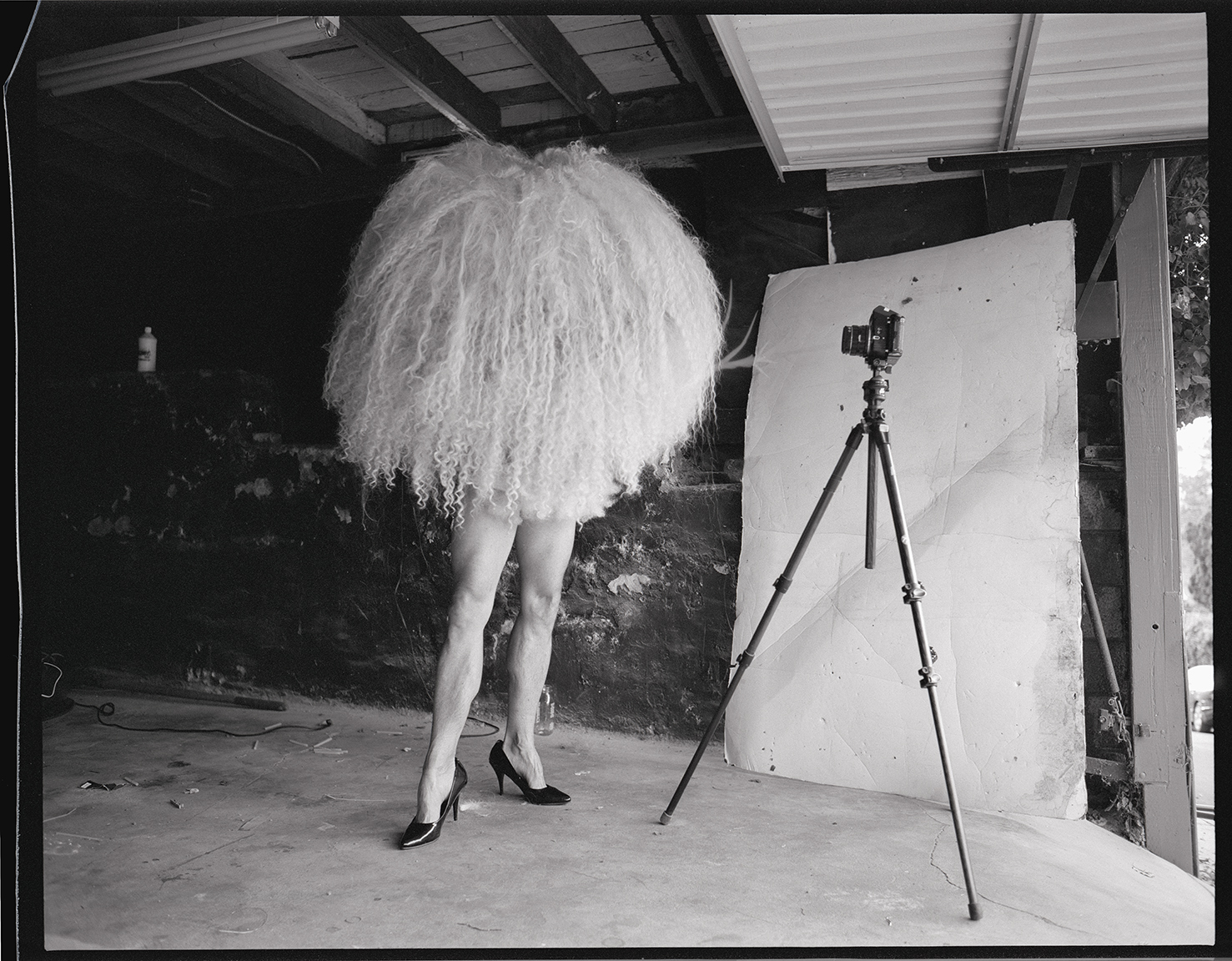

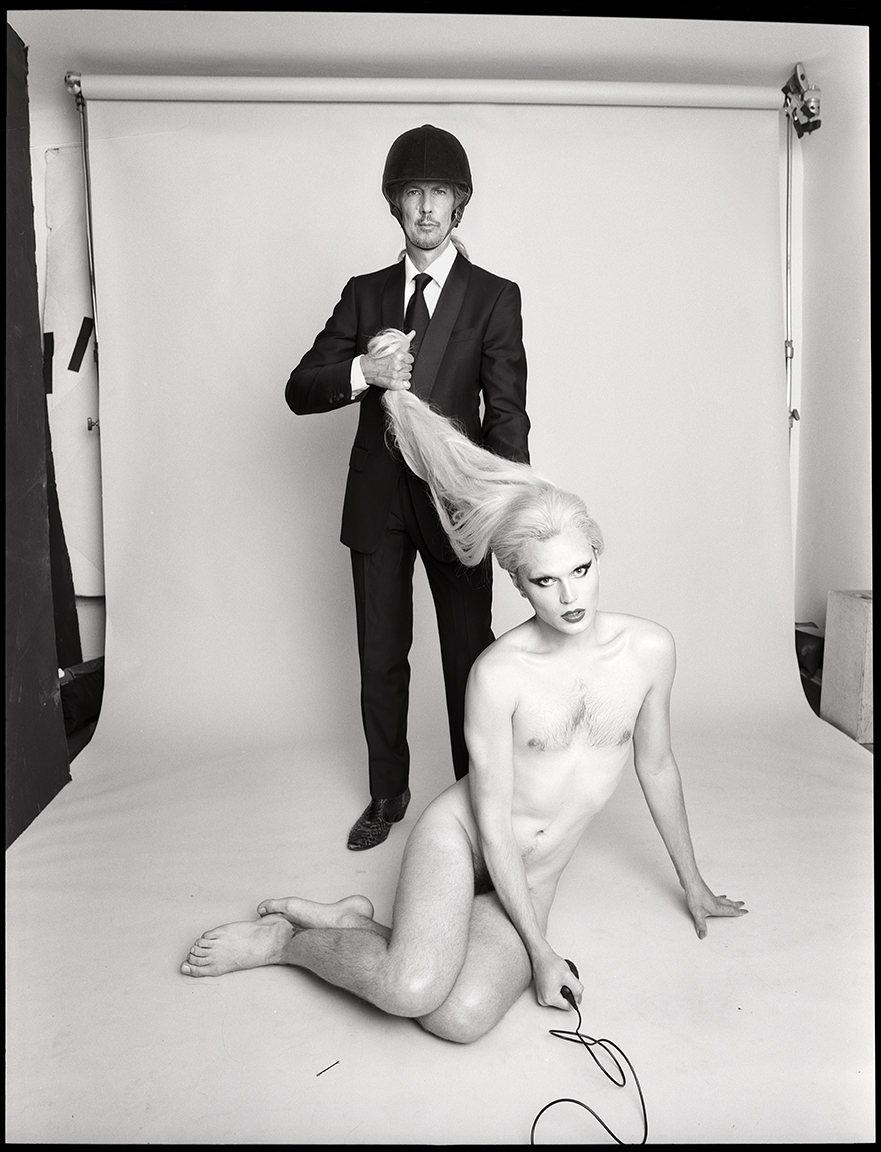

While the appeal of large format portraiture lies in its elegance and its keen ability to visually transcribe, the appeal of Gates’s work lies also in its audacity, vivaciousness and frivolity. In one image, an older man wearing a horse riding hat holds the photographer’s long flowing wig as if they themselves were a horse. The conviction and effortless elegance of the image reveals Gate’s sensibility—one that is rooted in both beauty and irony. Whether the photographer be nude hanging upside from a rope or leading a group catwalk in an empty garage, their raw and inventive use of props and costuming reveals wholly unpretentious images—imbued with a playful innocence, joy, and a sense of becoming.

Olivia Noss: Cyrus Dunham writes in the introduction of your book that ‘Imitation is as profound a practice as embodiment.’ What struck me most about their introduction was the notion of role play in photography as a way of becoming closer to who one might want to be. Was this something you were aware of when making this work? Do you feel that image-making helped you unearth your own identity?

Michael Bailey-Gates: There’s a handful of images in the book that I talk about as getting a yearly physical at a doctor’s office. They’re shot on a gray background—pictures of myself probing. This way of working doesn’t unearth much for me, but the pictures confront what’s already there by sharing it with others. That’s how a doctor’s physical is different from just standing at a dressing room mirror, you have a stranger examining you.

Olivia: What is your interest in bypassing gender, rather than addressing its fluidity?

Michael: I was out to eat recently, and there was a kid at the table next me ripping apart his dessert to eat only the raspberries. The table was a mess, and I don’t think he ate anything else. When I think about that phrase ‘to bypass gender,’ I think about all the mess of that table—all the parts thrown aside to focus only on the juicy part. Gender is one part of the whole. But it’s never the whole picture.

Olivia: Do you feel as if your images strive to represent intimacy on a broader scale, more so than specific identities?

Michael: Of course. I always want to pull back, look at what’s behind. Seeing the whole thing is intimacy.

Olivia: There is a real element of play within your work. Was there ever a time within the trajectory of your work where you steered away from this?

Michael: Photography can be very stern or serious, [in its] idea of documenting the truth of something, an era, a person. I spent some time making stoic pictures of people. I wanted to be honest and factual—[to] traditionally document. I don’t remember what shifted, but I think of Yvonne Rainer and her book title, Feelings are Facts.

Olivia: What were your thoughts behind the title of the book?

Michael: A Glint In The Kindling is my first book, hopefully the start of many more. Growing up, we heated our house with a woodstove, and first you had to get the kindling burning before starting a larger fire with a spark. This seemed fitting, in feeling, as a title.

Olivia: Can you expand on the importance of joy to you, both as a radical act and one that punctuates more of your deadpan images?

Michael: Joy is harder to see in pictures, besides the commercial ones selling a product with a smile. In this book, I wanted to capture a genuine imprint of myself and the people around me, and it didn’t feel genuine making only heavy pictures of my friends. That’s the wonderful thing about pictures: there can be both joy and grief in an image. I tend to lean more [towards] joy.

Olivia: You have a real propensity for fantasy and take such an inventive approach to the construction of props and scenes. What inspires these constructions?

Michael: One of my favorite art collectives was The Transcendental Painting Group, a group of abstract artists that shared a visual language and communicated via long distance through their work. These pictures were made to communicate with my own group of friends, to reflect back [through] a shared visual language. Flipping through the book quickly, you see angels, babies, horses, bows, and candles. Sets help portraits talk more [and] expand that vocabulary.

Olivia: What did you hope to get across in the making of this book?

Michael: Looking back at old work is difficult for me. When working with my gallery on this project, the director Jasper Bode said something along the lines of, ‘Before you can move on to the next, you need to document the old.’ There are a lot of intentions around making this work. It’s very personal, but the book felt like a place to go to bed, or give the work a place to rest.