The Brazilian photographer joins Document to discuss his zine, which documents friendship and love amid an oppressive political climate

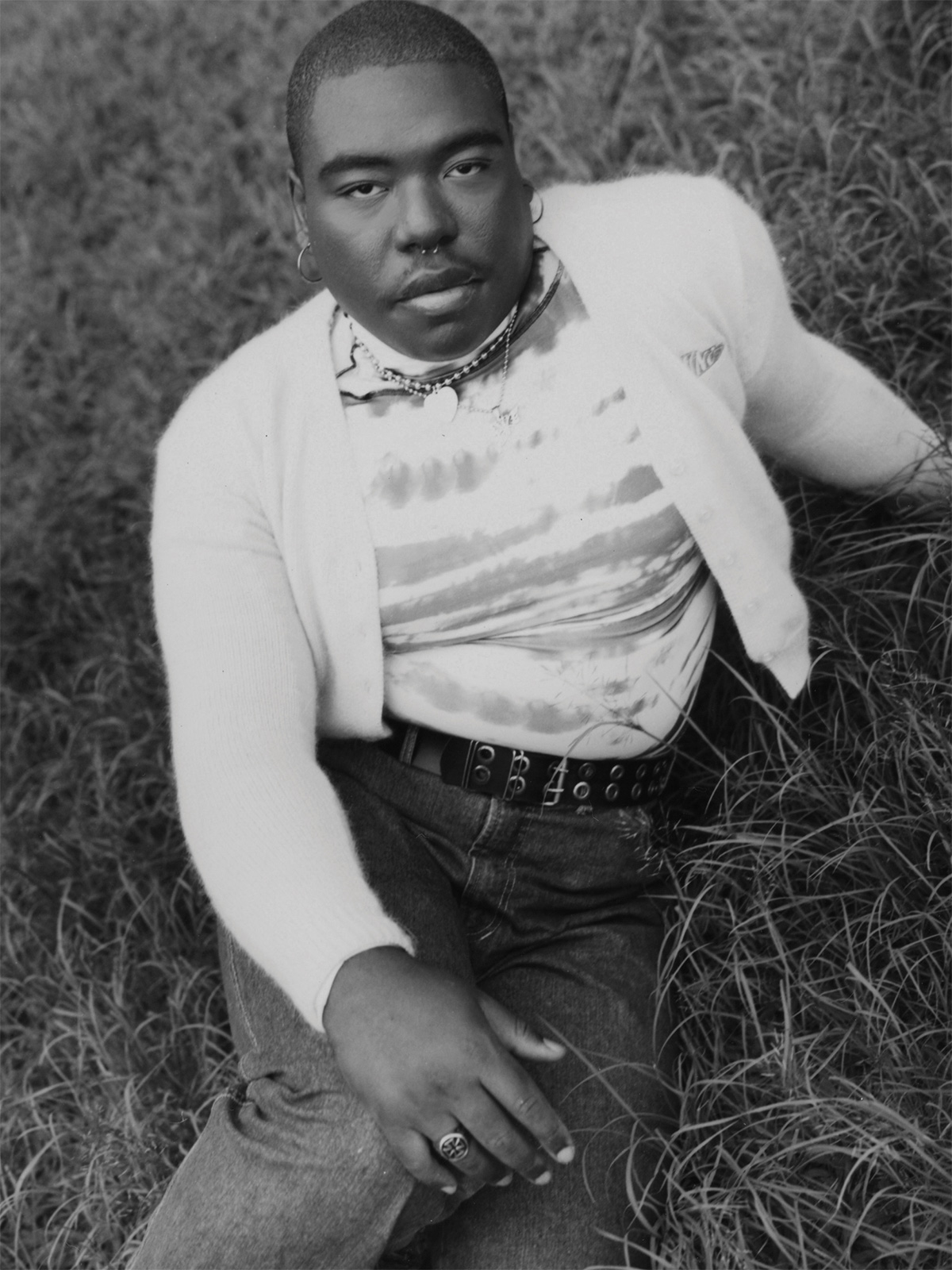

Guilherme da Silva is a Brazilian, analog-based photographer whose work centers largely around queer male experiences. In his new zine, Overture, da Silva’s images take on the carefully staged grace of paintings in order to construct a queer heaven, or Eden.

The photographer was inspired by a 19th-century painting by Thomas Eakins, entitled Arcadia, that depicts three nude figures in a sunlit meadow, splayed out peacefully on the grass, playing wind instruments often associated with heaven. The figures themselves seem to bear a celestial aura, shot in dappled light or at sunset, imbued with their own heavenly glow.

His work is punctuated with a series of playful and vibrant nude illustrations by Lucas Bassetto, whose drawings depict men resting languidly in pinks, greens, and blues that offset the muted palette of da Silva’s portraits. Whether it be feet intertwined, figures embracing, or a figure donning a flower crown, the drawings present a modern day take on the languor of Eakins’s paintings, while illustrating a more immediate allegory to terrestrial paradise.

The opening poem of the zine, a section of “Burnt Norton” by modernist poet T.S. Eliot, sets a precedent for the tone and content of the work. In the last three verses in the poem, Eliot writes, “Time past and time future / What might have been and what has been / Point to one end, which is always present.” This passage carries relevance in da Silva’s series, as many of his subjects appear to sit for the camera in a meditative state. The rose garden that the poem is set in is reminiscent of the Garden of Eden, where two subjects follow the prescient voice of a bird who tells them, “Go, go, go… human kind / Cannot bear very much reality.”

Its own form of respite from reality, da Silva’s Overture debuts an idyllic vision of a world unfettered by often harsh realities of queer existence. Shortly after the project’s release, the photographer joins Document to discuss his approach to his craft, the power of poetry, and producing queer art in an oppressive political climate.

Olivia Noss: You construct a world where your subjects exist in a paradise of sorts. Could you elaborate on why you seek to create Arcadia through your images?

Guilherme da Silva: Since I started [photography], I’ve always tried to transport the viewer to a different reality, even if it’s documentary pictures. When I started the project, I knew I wanted to create a realm where people [could] be themselves and feel protected from the real world.

Olivia: Where did the zine’s title, Overture, come from?

Guilherme: I’ve always wanted to do self-publications, and I thought the word fit perfectly as this is my first project ever. It’s the beginning of something that I really believe in.

Olivia: There are musical and poetic associations with the title itself, and it seems to imply that there is a continuation, something else to come. What do you see coming after this?

Guilherme: Yes, definitely! I’m really inspired by poetry and music. I actually used part of a poem from T.S. Eliot in the zine, and during the process of editing, I listened to a lot of Lana Del Rey. I chose this title because this is the first of many publications I want to make.

Olivia: What were your thoughts behind including Lucas Basetto’s illustrations of nude men in your series?

Guilherme: Lucas, my boyfriend, and [I have] been together for four years. I didn’t know that Lucas knew how to paint until the pandemic. During [that time], we started to research queer history and he got really inspired. He started to [make illustrations] and I really loved the color palette. It adds something to the pages, as we have almost the same subject, but in different mediums.

Olivia: How does your Brazilian identity inform the way you make pictures?

Guilherme: I don’t think you can see a lot of that in my work. I don’t use Brazilian codes in my pictures, because I want to make the viewer feel [as if] they are in a place that could be anywhere. But being Brazilian is very hard when you want to work with photography, and it can be even harder when your subjects are queer people, because they are very LGBTQ-phobic. I struggled a lot trying to bring this project to life, but I stood up for myself and here I am.