For Document’s tenth anniversary, the artist joins independent curator Monique Long to expand on the lasting allure of the iconic ensemble

The history of diasporic Black people in the United States could be told through a series of landmark eras commensurate with dress culture. With the mid 20th-century Civil Rights Movement, for example, one might analyze the clothing choices of Martin Luther King Jr., his cohort, and other leaders. Why would the men march in protest for miles in the hot sun in suits, or the women in dresses and heels? From the Antebellum Period to the present day, for African Americans, there has always been a masking element to style. Historically, Black dress can be defined in part as negotiating both invisibility and hypervisibility. The desire for respectability and, ultimately, a rejection of that desire.

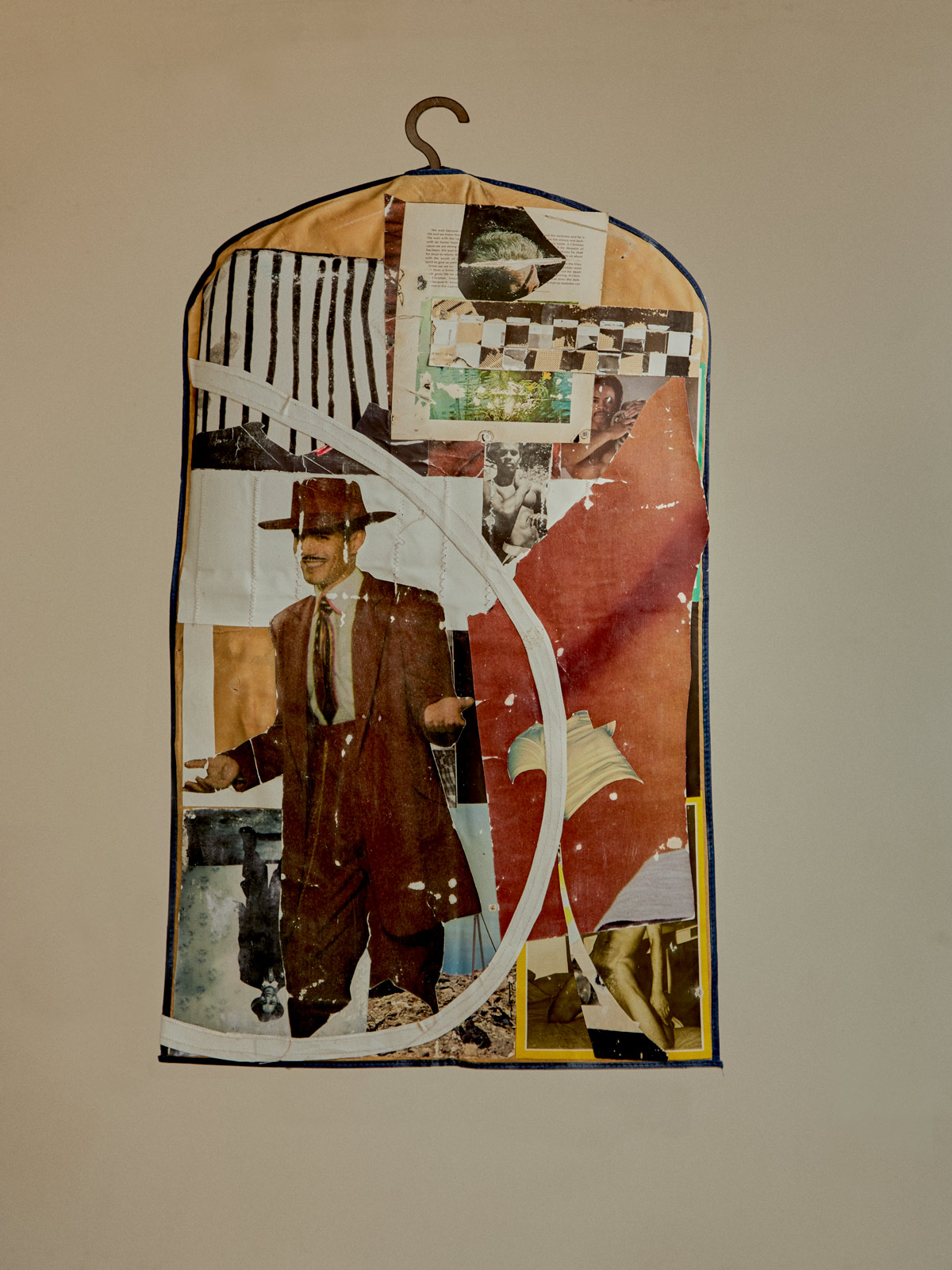

Enter artist Troy Montes-Michie: In his current body of work, he focuses on the zoot suit. The zoot suit emerged in the 1930s as a “Harlem-style suit [with] padded shoulders; 43-inch trousers at the knee with cuffs so small it needs a zipper to get into; high waistline; fancy lapels; [and] bushels of buttons,” according to anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston in a glossary of Harlem slang she published in 1934. With performances by New York jazz musicians documented in movies, the fashion trend migrated across the United States. During World War II, the suit became symbolic of rebellion and subversive self-expression, eventually making Black and Latino youth targets of violence by those who thought the style was too extravagant during the austerity of wartime. Through his own making and autobiographical narratives, Montes-Michie, who received his MFA from Yale in 2011 and teaches at Princeton, has been exploring how the trend manifested in El Paso, Texas—the town where he was born and raised as someone with both Black and Mexican heritage. The works include collage, sculpture, drawing, and textile-based installations where the bespoke suit is the physical and ideological support for the art in its many iterations. These themes are also the focus of his solo exhibition currently at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles, titled Rock of Eye, a term which means the ability to work from intuition rather than by standard methodologies. The exhibition encompasses fashion history, his own migration story from El Paso to New York, and the zoot suit, past and present.

Monique Long: I have a lot of questions about your exhibition, Rock of Eye, that I’ll be asking you, but I wanted to know how you first encountered zoot suits and how you made the decision to use them as material for your work?

Troy Montes-Michie: I first encountered them just growing up in El Paso, where they were such a part of the culture. I think people still have them custom-made for special occasions, like quinceañeras, or even as part of lowrider culture. And then just films—there’s a pretty popular movie called Zoot Suit. I started working with the zoot suit [during] the 2016 presidential election, I was really enraged about a lot of the rhetoric being used about Mexican people and border towns. I really tried to center my practice on speaking about El Paso, and that led me to [the zoot suit]. The more I started to research it, I discovered—which I guess people already knew in El Paso, the term pachuco, the Mexican zoot suiter—the style originated in El Paso, Texas. From there, it went through the line of migration toward LA with Mexican railroad workers.

Monique: In your artist talk with Tina Campt, I was really surprised when you said that people still wear them, and I was wondering what a contemporary zoot suit looks like. How does it depart from our collective memory of a zoot suit?

Troy: It’s kind of the same. [There’s] still a bunch of zoot suiters in Juarez that get together to dance, but they’re more colorful. So red, purple—the hat plays a dominant feature with a large feather—the suspenders, probably a crucifix chain over a button-up shirt, and then also a side pocket chain.

Monique: I was thinking about [comedian] Steve Harvey and his signature suit—it’s not exactly the same, but it definitely mirrors the proportion. And they were very popular in the ’90s. I think he even had his own line. But I started thinking about borders in a way that I hadn’t before. I’d seen your show and the narrative around your work, and was thinking about other lines or borders that you travel, like the line between fashion and art, present even in the title of your exhibition, and the Photo Tex on the floor, and the border between abstraction and figuration. Can you talk about [how] the ways in which you think about borders manifest in your work?

Troy: I’m glad you noticed that. Sometimes I certainly can’t help including borders just because of who I am and my own experience, but I think about the border a lot. When it comes to collage, there’s been so much discussion by art historians about the use of the cut. For me, it’s less about the cut, but [instead] thinking about the contour. The contour line of the body or of territories are these outlines that define a part of me. It’s almost like tracing, so when I’m using collage it almost feels like I’m outlining something or going over something again. It does ultimately [get] cut, but it’s a way of removing and replacing, or reinserting something else, like other histories or materials. I owe a great deal to the book Borderlands by Gloria Anzaldúa. It really blew my mind, because I’d never read a book that totally encapsulated that experience and understanding of growing up on the border. She even goes further and breaks those borders and talks about the difficulties of living in that territory.

Monique: In the catalog for Rock of Eye you state, ‘In my collages, the act of appropriation is an attempt to wrench open or liberate this place where these men have been buried. And buried solely as an enticement for the white gaze. I wanted to go in and cut that up. Sometimes even the simplest, smallest gesture can serve as a step towards something else. Just by scavenging to find these magazines and then taking time with them, cutting the men out, I feel it’s already doing something else.’

“I always think about what’s beyond the frame that’s been provided to us, and how that would change our old perception. But we’re not privy to what’s beyond the boundaries of the photographic record.”

I think not only of the cut, but also the crop. Its importance within the history of photography, and how so much of the story lies not just within the crop but outside of it, and how that narrative is constructed in relation to your work. I guess it’s synonymous [with the cut] in many ways. Because they’re parallel—there is an original sort of editorial or magazine editorial, and how you’re interrupting that, and reimagining it, is happening simultaneously. But that’s just my take on how you talk about collage and this art-historical narrative about the cut.

Troy: The crop is kind of crucial. I think my interest in archives is [an interest in] the way that photographs are supposed to be some kind of record in time. I always think about what’s beyond the frame that’s been provided to us, and how that would change our old perception. But we’re not privy to what’s beyond the boundaries of the photographic record.

Monique: Camouflage comes up quite a bit in the exhibition, and when you’re talking about your research and work. What’s the importance of camouflage’s own history as a garment and in military history? And how do you think about it in relation to your practice?

Troy: The research of camouflage came [from] just thinking about, again, El Paso. I didn’t realize what a highly militarized environment it was until I moved. It’s the presence of the Border Patrol, then also the nation’s largest army training area called Fort Bliss. I grew up seeing camouflage my whole life, seeing military presence. [I was] writing an artist’s statement and I just kept seeing this word, ‘camouflage.’ So I started to research it. I was so surprised, because a lot of camouflage theory was furthered by the invention of the photograph. Around the same time [as the rise of] the zoot suit, a lot of artists were forming these camouflage societies, and I was most drawn to this one theory called ‘disruptive patterning.’ That’s how I related it to the zoot suit in that it’s a form of camouflage that isn’t necessarily invisible. It’s supposed to be hypervisible, but disruptive and formless. It made me think of the way that these Mexican youths were wearing the suit to create their own identities as first-generation Americans, and then that confusion from the white audience, because it felt like a disruption from the norms of style of the time.

Monique: I’ve heard this or read this somewhere, and I’m still trying to find more documentation or research about it. Apparently, the British are credited with inventing camouflage, but really, they were defeated by the Maroons in Jamaica and Queen Nanny because she was a master of camouflage. The British soldiers said, ‘The trees were coming alive!’ They were so disoriented by her use of camouflage in battle that she was able to prevail in Jamaica.

Troy: I haven’t heard that, but that’s amazing. I believe that.

Monique: It’s so humiliating, I’m sure the history has been obscured. I found little, tiny threads about it. But it’s definitely downplayed, which makes me think it’s correct. I’ve spent a lot of time just looking at Black American history and fashion. There’s a masking element that’s been evident since slavery that I think is interesting; not just Queen Nanny, but in the United States, enslaved people were able to escape by wearing clothes that they made. Oftentimes, when they set out to escape, they knew they couldn’t in the clothes that were given to them, because the clothing would give them away. So they would make beautiful clothes, because they often had those skills that they used on the plantations. What does that legacy mean, to be able to use clothing as a means for escape and freedom?

I wanted to talk a little bit more about the exhibition, Rock of Eye. One of the curators mentioned that you had a very specific vision for the design of the show—and it’s so beautiful, and has an immersive quality to it. I wanted to know, what did you want the design to convey to visitors?

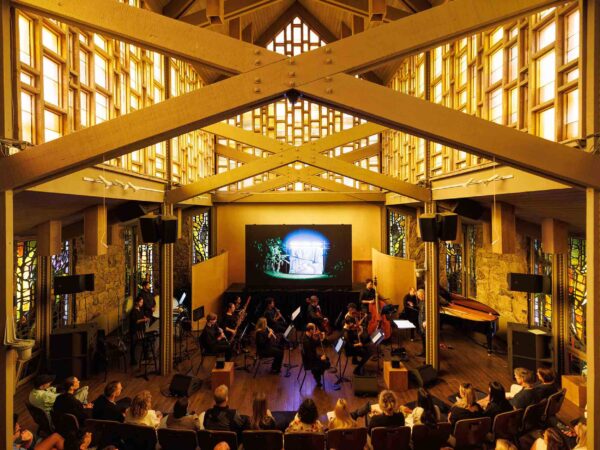

Troy: I’ve been working on that project for so long with the curator Andrea [Andersson]. It was supposed to open in 2020, but the pandemic kept stalling things. By chance, I happened to work on the catalog first. It was interesting because I didn’t know what the work was going to be yet. With the book, I decided to give the viewer a sense of all the different fragmentation that happens in the woven collage works, so they could see my materials unfiltered—the drawings that get glued in, a lot of the vintage advertisements and magazines, the clothing patterns. I think about each show as a chapter in this zoot suit project. It made sense that the book really influenced how I was going to think about the show. It answered a lot of questions I still had lingering in my practice by [prompting me to think] about this type of fragmentation sequentially, and then reading over the essays. [The museum’s gallery] is so large that I felt it would be more interesting, instead of making newer work, to take a lot of my older works from right before I started the zoot suit project up to 2020, and then bring them back into a dialogue with each other. I think of the almost like the book. I wanted the viewer to feel like they were within one of the spaces in the woven works, with the photo on the wall and imagery and contour lines and clothing patterns on the floor.

“I think that’s what’s nice about the suit, because it was seen as this flamboyant, garish garment, but it had a function for dancing. The person wearing it needed that legroom so the seams wouldn’t burst.”

Monique: Toward the end of your conversation with Brent Hayes Edwards for the catalog, you start talking about music. I was very interested in that because so much about the zoot suit—especially for those of us who know the origin story of the zoot suit—we see through this filter of the past, and the documentation of it within performance. In particular, I think of Cab Calloway, because he was the frontman for his orchestra and he used every part of his body to express himself, from the tip of his hair to the end of his spats. The suit worked to emphasize his performance and what the band was playing. For me, the zoot suit and the music of the period are inherently connected. You have a different background, because you’re looking at pachuco culture, and the way they express themselves, and the trauma that they experienced because of the way that they expressed themselves. But I wonder if you ever thought about Cab Calloway in particular, or if you made any work around music and zoot suits.

Troy: Yeah, for sure. The project started mainly because my father was talking about this famous zoot suit that had originated in Mexico. I thought, Well, how did Cab Calloway find the zoot suit? The more I researched it, I realized, Okay, wait a minute, the zoot suit was actually furthered by jazz clubs in Harlem, [and] Calloway was a predominant leader in that. Then I realized that it was those moments that caused a jazz craze throughout the country, and then it went to all these other, larger cities throughout the US. Music is super important. So when I’m researching, I try to take in everything from that time period: looking at style and print media, listening to jazz both as we know it and [by] a couple of Mexican-American bands from that time. Ultimately, I think that’s what’s nice about the suit, because it was seen as this flamboyant, garish garment, but it had a function for dancing. The person wearing it needed that legroom so the seams wouldn’t burst. But it was this nice way of thinking about my own journey, growing up in El Paso and living in New York. I [realized that there] was a way that I could bring both of these histories together, centered around one garment.

Monique: [In Rock of Eye], the suits that are suspended in the center of the gallery almost read like a monument. But it also has this aspect of time. I think Tina [Campt] or maybe Brent [Hayes Edwards] called it a seriality. It also embodied the evolution of a garment over time, but that’s my own reading. It’s more of a metaphor, but I love the effect of the suits that are suspended.

Troy: They’re a challenge to exhibit, but I was really happy with this show. Oftentimes, if they are two-sided, they end up just being on a hanger against a wall. But I want to look around this garment and see all the different modes of collage that are happening. That felt like a nice moment in that room, and then also [part of] the larger totemic sculpture.

Monique: It was really satisfying to have the perspective of both sides. Many times, it can be heartbreaking, because you just want to see everything and you can’t. So there’s this denial or refusal to be able to see. There was something else that struck me during one of your interviews: You said that you work with a tailor in El Paso, so all the zoot suits that you work with are to your measurements. Is that correct?

Troy: Yes.

Monique: Wow. A lot to think about there, especially with respect to portraiture. There’s a nice moment in Rock of Eye where you talk about Frida Kahlo and [her painting from 1933], My Dress Hangs There. In varying texts it’s considered as not a portrait, but it seems like such a portrait to me. There are a couple of citations or references in the exhibition to your influences, including the work by Kahlo and also Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, which I thought was interesting, because they’re both migration narratives. For the protagonist in Invisible Man, his story is commensurate with a migration that goes horribly wrong, and [it’s] the same for Frida Kahlo. I wanted to talk about this idea of traversing borders and the disillusionment of that, and also any influences that you might have in the fashion industry.

Troy: I didn’t pick up on the dress in the Kahlo painting as a marker for migration, but I find that to be an accurate observation. During this time in self-isolation I realized that, as a person who was trained as a painter and loved painting portraits, I was still thinking about portraiture—it’s just become more abstract. I was drawn to Kahlo’s use of portraiture and the way she was able to give the viewer a sense of her emotional state and sentiments through symbolism. There is a rawness to her work, and this specific painting highlights her disdain for the industrial landscape of New York City and inserts the dress as her stand-in. It symbolizes the way in which a garment could encapsulate identity.

There’s a [magazine interview with Ralph Ellison that predates the publication of Invisible Man] where Ellison interprets the popularity of the zoot suit as an attempt by Black working-class youth to reject middle-class ideas of respectability. I liked how that almost seemed the same in terms of Mexican-American identity—the rejection of this type of assimilationist fashion that their parents encouraged them to accept so that they could fit into society.

“I thought I would be able to find vintage suits and was inquiring in Harlem, not knowing they would be hard to find. Everyone in New York was like, ‘What are you going to? A costume party?”

In terms of designers I look at, I really enjoy the work of Willy Chavarria and his attention to the silhouette. After working with the zoot suit for many years, there is playfulness in the way the garment is oversized and armor-like. I see Chavarria’s work as a contemporary spin on classic silhouettes from pachuco and cholo fashion. I also enjoy the way the garments break gender norms of masculinity. I’m a fan of some iconic creations by Martin Margiela, such as the 2006 waistcoats created from playing cards and leather bands. Using disparate materials for garments is very much in the language of assemblage. It also makes me think of Lorraine O’Grady’s performance gown stitched from [white] formal gloves for Mlle Bourgeoise Noir.

When I started doing the zoot suit project I thought I would be able to find vintage suits and was inquiring in Harlem, not knowing they would be hard to find. Everyone in New York was like, ‘What are you going to? A costume party? What’s going on here?’ I worked with a tailor in El Paso, Señor Alvarez, who made a series of beautiful custom zoot suits.

Monique: I think it’s difficult to understand, with our contemporary eye, why the zoot suits would have been so shocking, because we live in an age where there’s such an amalgamation of styles and expressions. But I could see where it would be considered transgressive, because of how it exaggerates the body. It both conceals and also highlights—you’ve made that point as well—because the shoulders and the legs are so exaggerated, the waist becomes very nipped and unrealistically small.

Troy: I think it was just more flamboyant because there was World War II rationing, so that’s how they were able to make it illegal. It seems like the suits before [the war] were a little bit more broad, but still in very mundane colors, like grays and warmer brown tones. I’m thinking of Spike Lee’s Malcolm X movie—that checkered plaid and super bright color feel like a good marker for African American style, and the way that it’s always set itself apart from the mainstream. I just remembered Bianca Saunders too.

Monique: As a fashion influence?

Troy: I’ve collaborated with her a little bit. I like watching what she’s doing right now in terms of thinking about masculinity and this idea of draping fabric over the body. It’s interesting, the new work as it progresses, and I’m so happy that she’s getting the success she deserves.

Monique: You’ve devoted an entire body of work to one garment. Do you feel like you have exhausted its possibilities as they manifest in your work, or is there more to explore? Are there any other items of clothing that you’re interested in studying, or are studying?

Troy: I don’t think that it is possible to exhaust all the possibilities of the zoot suit since it’s tied to so many various histories in fashion and culture. I continue to be fascinated by the politics of fashion and the notions of power and class that mainstream culture attributes to style.