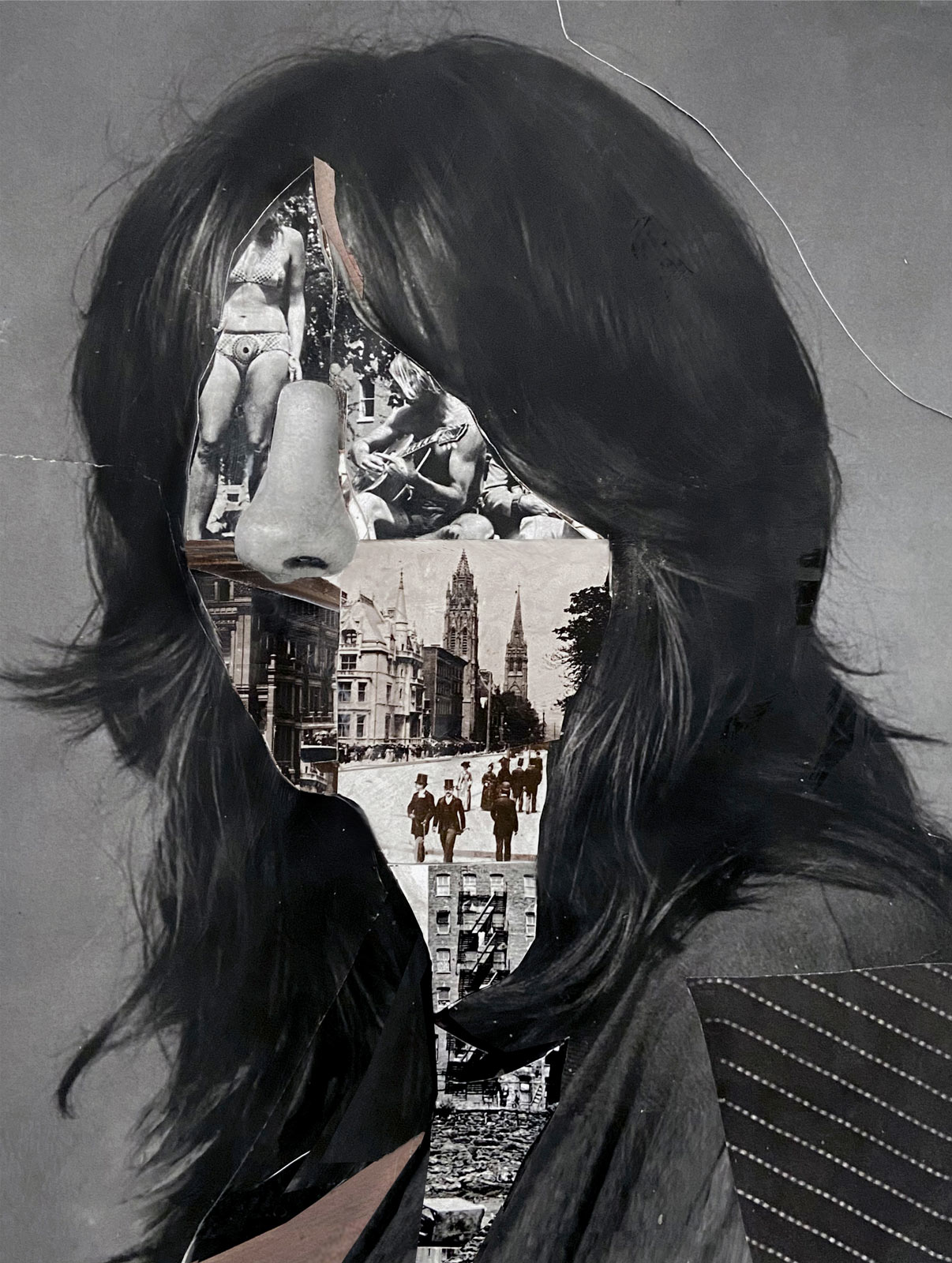

For Document’s tenth anniversary, the writer merges personal, political, and geological histories to document a city in flux

Since plants preceded people, the history of New York is not particularly a human story. Plants and trees changed the atmosphere of the planet—and that’s why we have oxygen and can breathe—and the growing things have been dropping their leaves, branches, and ferns, and even trunks into the waters that surround the land. What lands in the water (that’s organic) gives minerals and nourishes the fish. Point of fact, what New Yorkers know as the East River was never a river, but is actually a saltwater tidal estuary formed 11,000 years ago by glaciers. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the ‘East River’ was continually narrowed by those who wanted more and more land, and the ‘river’ kept flowing faster and faster. It’s so New York.

People first started living here around 9,000 years ago, and the Lenape came in 6,000 years later. The first permanent inhabitants of the island, about 15,000 Lenape were here when the Dutch arrived and began colonizing. One Dutch governor, Willem Kieft, tasked himself with eliminating the Lenape entirely from Manhattan, in particular from the attractive cove of what we now call Corlears Hook, where he killed about a hundred in their sleep. The very spot of Kieft’s massacre was recently deforested by the city as part of what is known as the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project, aka ESCR, which is described in the media and by the city’s press releases as a climate resiliency plan. A flood plan! Though many residents feel that it’s real estate, and nothing more. Well, actually, it’s ecocide and even genocide if you look at the big picture (health-wise) of where we live.

East River Park was flooded once for three hours in 2012, and never again, but the city is spending almost two billion dollars to protect us from storms by destroying it and putting a concrete levee where it increasingly isn’t, and then sticking a new park on top of that. That’s the plan. It’s all New York! Every moment, every bit of it.

Indigenous people have been at the front line of our park’s defense. And the Lenape, it is worth stating, are coming back to New York State. Officially, there are three federally recognized bands of Lenapeyok in what is currently called the United States, and three in Canada. They are the Delaware Tribe of Indians and Delaware Nation in Oklahoma; Stockbridge-Munsee and Mohican Community in Wisconsin; Moravian Delaware of the Thames, Munsee-Delaware Nation at Munceytown, and Delaware of Six Nations in Ontario.

I set foot in New York for the first time in 1964 with my family. It was the only time I ever changed my hair color. I dumped bleach on my bangs. I did that once, it was an ugly orange, and New York saw it. We stayed at a motel in Queens, in Jackson Heights, and I mostly remember how hardcore the subway was—all dark green and military-looking. What is New York? Kids I knew from Boston came here in the Summer of Love and did a lot of speed, and they came home skinny and stylish with their teeth sticking out. I wanted to be close to the flame but not look like that. It’s actually hard to write about New York since I only have one life, and I’ve pretty much covered it. I got here for good in 1974, and I can extrapolate two things from the past 50 years: One, it was easy. New York was easy, and it’s still easy, that’s why I liked it. It’s like discount shopping. You rifle the surface a bit until you see something you want and you grab it. Two, people here are generally committed to a kind of immediacy and excess. This is not a rehearsal. It never was. This is actually it. People in New York (if they weren’t born here) always have an arrival story. You came with a friend and the friend left. ’Cause if ‘it’ didn’t like you, you didn’t stay. I’ve never heard another place described in such a predatory manner. I’m never surprised by anything, especially now, which is probably New York’s end. But it’s also the end of everything, so New York would have to get there first. That’s my take. It’s a big, hungry city that’s killing itself. And still, I want to watch.

While you’re new or young, people in New York like giving you things. Everything gets framed as a gift. I do it too. I think people see their own status through their capacity to have things to give. My friend Helene’s boyfriend Herbie, a real New Yorker, hooked me up with a job at the West End Bar and I started getting some history immediately. Everyone had a backstory: used to be a junkie, used to be a Columbia radical, everyone knew people in bands and could get in free. The more I go on, the more I realize the ease and the excess were one and the same. It was a hunger (of course) that worked both ways. There was nothing anybody wouldn’t do, and in my shy way, I tried to get like that. I dwelled for most of my life in the city of New York in a supreme feeling of next-ness.

“Everyone had a backstory: used to be a junkie, used to be a Columbia radical, everyone knew people in bands and could get in free. The more I go on, the more I realize the ease and the excess were one and the same.”

I did acid for the first time in New York, and acid is really how my life worked and maybe still does, ’cause I learned to think that way. There was just something completely pulsing. It’s possible it’s an outcome of the soft, white marble the city is perched upon. Nobody’s seen it for a long time, but it’s down there. (Read Hugh Raffles’s The Book of Unconformities: Speculations on Lost Time.) But then it got different. I think the world began mainly traveling through institutions (about the same time it started speaking though those little demons on the internet) by the ’90s for sure. New York became more like everyplace else. But the marble’s still here. I don’t mean that the Whitney program is bad or that graduate programs are, but previous realities were more embedded; by moving your body around the grid of the city, you would touch things and you became immersed.

I’ve been around for most of New York’s disasters, and I’m truly sad that I missed the interiority at that most intense point of the pandemic. Simultaneously with the enormous tragedy of the people who died of COVID, others really enjoyed the momentary return to the old thing. It was empty the way the neighborhoods were empty in the ’70s and ’80s, and it was quiet. While some people were dying, other people watched the city have its last gasp. You could hear the birds sing. In the future, it will be remembered as prophetic. The homeless could take their space like they always did. Our current mayor refers to them now as a cancer.

I remember an ex of mine telling me how her late uncle’s paintings had been deposited on the street by some malevolent subletters. It seems unfathomable, but it happens all the time. They probably just wanted more room, what everybody wants in New York. It was devastating for my girlfriend, but for somebody else—what a find. Those paintings will turn up perhaps a hundred years from now. The sloppy solidarity of New York still creates history. It saves things while it destroys. There was the park. There was this skim of park along the East River that was not a river.

I don’t know when I first went down there. I moved to the East Village in 1977. People say you’ve seen it all. Well, sometimes. We would walk our Millers down to the park and run around the track and then head back to the neighborhood and the night would begin. Drinking stopped and the running continued. When alcoholism goes into a dormant state (hopefully for the rest of your life), you actually begin to get space. You require it. You look up and go, Wow, look at the buildings. I discovered the park majorly then, when I was too poor to join a gym. There’s a tree I’ve been putting my leg up on for at least 40 years—perhaps it is an elder—and I give it a stretch. I was never a long-distance runner, but East River Park was how I began understanding the tree-like experience of being human. We’re in this together. Though they are apparently ‘still,’ we share a long narrative with them. You begin to move, the body feels heavy while running, the feet pound sadly, and your mind is full of syrupy anxiety and despair. And then it begins to lift. It’s like sap. Air began flooding through the thing of me. It was easier and easier to run, and at about two miles I was virtually being carried. Running on the track or, later, along the esplanade, which over the years would open and close, gave me the island feel. I began to understand New York not just as us, and what we wanted, but as land. And land made my sanity great.

When Robert Moses built it in 1939, East River Park was the way he made his plan to build the FDR highway more juicy. This park is for the working people, he claimed, this park is for everybody. It was more about class then, so he probably meant everybody white.

For years, the park had a twin—the dilapidated state of the West Side Piers, and you know how that went. We used to consider it a vacation, going over there. Sitting with my beer, or later with my iced coffee, at the end of the rotting pier with my girlfriend. I actually didn’t think of the East River as someplace to go. It was just there. It was the big cousin of all the tiny community gardens in the neighborhood. In the ’70s it was commonplace to get robbed. In the early ’80s, too, there was a runner who was shot by some random guy who thought of them as something in a cage to take a pop at. Lots of us thought about that as we turned. I did my laps again and again, going one tree, two tree, three tree. That one big tree that I lifted my leg against whose destiny now is only to get cut. Why? Because it’s what’s left.

“The sloppy solidarity of New York still creates history. It saves things while it destroys. There was the park. There was this skim of park along the East River that was not a river.”

I’ve had my back up since fall of 2020 when I first learned the park was about to be destroyed. This park? Our park? How? In the years immediately after Hurricane Sandy (2012), and even right before, there was a lot of talk about sea level rise and how Manhattan was going to be flooded, and that was that. This place will be gone, we laughed. A plan was developed by the design firm XYZ called the East River Blueway, and it put a cap on the FDR, because people knew about the effects of carbon dioxide, and they planned wetlands and an expansion of the acreage of the park by building on top of it. The Blueway bounced around for a couple of years, and after Sandy, it never came back. What did come was a design competition to reimagine the coastline of New York. The Bjarke Ingels Group won, and the component that directly involved East River Park was the ESCR. It also considered wetlands, not so much about covering FDR. It was a less visionary plan for sure, but a major feature was a berm that ran along the west side of the park. It was actually unnecessary, because all we really need is a two foot wall to manage the very minimal amount of flooding that had actually occurred. The original version of ESCR left the park intact. That berm eventually became a negative focus for the city, because you would be building it on top of Con Ed wires and a lane of FDR would have to be closed for five years, and so on. The plan generally bugged the city because they said it was too much work. But just hold that thought for one second against the reality of human values, the effects of trees on people, animals, water, and fish. The park was opened to the public more than 80 years ago, and earlier it was the Lenape people’s, so it’s naïve of me to think of it as “ours.” But to ignore the effect of something as massive as fifty acres of green space on the lives, mentality, and overall groundedness of the people who live in a place makes me wonder, widely, what a city is. Because what is a person? What is a tree? Is that not part of the calculation? If not, then where are we? That’s my only question in this history.

The shape of the original resiliency plan got hashed out in textbook fashion of how city planning works today. The community was involved. They were asked what they wanted. People said they wanted the park to remain, they wanted to see the water, they wanted flood protection. Designers and architects were also involved in these conversations, politicians were included. You can find details and even the heartbreaking transcript of all this earnestness on the internet. But why this process is typical of city planning today is that a simulacra of democracy (not a park) is what’s being constructed for the people, while the actual plan got cooked up behind the scenes. And, you know, we still don’t know what the actual new ESCR plan is. We fought and fought to get a piece of paper that was supposedly its rationale, which was something called the Value Engineering Report. First it was cited, then it was refuted—like it didn’t exist!—by our own city councilor Carlina Rivera, who flip-flopped so many times on which version of the plan she preferred you’d think she was one of those poor endangered fish. I think she was trying to figure out where she was going to swim. Finally, we got a heavily redacted copy of the document that, at the very least, told us that none of these neighbors and environmentalists who had been involved were in the room when they decided they would prefer to kill our park rather than thank it for all the days and years, and then save it.

I just want to reflect now, for a moment, on the state of global journalism. In Palestine, journalists get shot on the spot. That’s just what Israel does. They have a huge budget for something called hasbara. Which means spin. Which is repeated by the US government and the EU: Human rights violations in Israel and Palestine are not happening. And that’s that. In Russia, journalists are poisoned, we’ve seen all those empty chairs. They’re gunned down in the hallways of their buildings. Here, we take the slow approach to news. We say nothing.

Which is criminal. Because the destruction of 57 acres of parkland destroys us, too. It’s destroying my New York life. In terms of biodiversity and green space, “we” means that me and the animals and the insects and the squirrels and the trees are continuous. And the water and the air and the soil. The people who use the park are alive like I am, and if a park is killed, they die more than a little, too.

This park, East River Park, being demolished at this very moment, is not interesting news. Is New York media supported by real estate? Probably. What’s true? I don’t know. When I arrived in the ’70s, the city was mostly broke, and, as I understand it, the only way they got out of it was that Koch sold the city to real estate. When something big happens, it doesn’t show for a while.

When I think of all the empty lots, and the performance spaces with dirt floors, or made out of old gas stations or two apartments, they just pulled out the ceiling and the floor and that was it. Later, there weren’t any gas stations at all, and then they started taking down trees and parks near public housing—they call this infill—and sticking high rises in there.

But shhh, shhh, shhh. And live there. We have no alternative press that has the power to name and affect this illegal, legal, absolutely violent public process of seizing land in New York—whether that means that they are seizing your light by throwing up a high rise outside your window or simply removing the open air from our side of the river. Have you been down there? Have you seen it? It’s like a bomb hit it. They are moving through all 50 acres, cutting trees down one by one. Cherry trees in bloom? Buzzzzzzzzzz. This is every bit as bad as destroying the Amazon, because this little island of New York is polluted and overcrowded, and we need every damn tree to remove the fetid air of FDR and Con Ed. You know politicians love to say we’re planting thousands of new trees, but saplings and 120-year-old London planes are really different in terms of what they do for the air we breathe. Those little guys they’re planning might not even make it in this environment. Trees need cover, as in elders. There will be none. They are cutting them all down and no one’s saying a word.

“The park, we cannot say this enough, is a sponge. A sponge that is being extracted, one branch, one leaf, one root, one squirrel, one mentally ill neighbor at a time.”

We spent a week last fall occupying City Hall Park, but more accurately hanging out, standing up on milk crates and reading poems into megaphones and making speeches, making signs, doing yoga collectively, chaining ourselves to trees and taking pictures, posting them of course, making a wonderful weeks-long spectacle; we were bonding and parading with the taxi drivers who were out there, as well, blowing our horns and banging drums and chanting. We met some politicians, too. Brad Lander, then a city councilor, now the comptroller, listened calmly as we explained what we were doing. And his eyes were dead, that’s all. That’s one kind of politician. Look at Gowanus, he made the deal. Then Corey Johnson comes along. A gay man, youngish, son of a union leader, speaker of the city council. Once he was cornered by us, he twinkled with connectivity. He is the other kind. I’ve never heard about this, he candidly admitted, Would you send me some information? Here’s Sean’s number, and he wrote it down. But he was on the city council when they voted for the new, better, faster, deathly ESCR. For me, the moment of truth at City Hall Park was when Katherine De La Cruz, a young dancer and choreographer, took the mic and asked: “How do we know there will be any more 80-year-old trees?” I mean, some scientists are saying we will only have oxygen for 30 more years on this planet. And then what? Poof. I mean, what if they decided we were running out of resources and we simply needed to euthanize the old? I’m 72. Take me! That is exactly what they are doing. People at Corlears Hook cried when they cut the cherry trees. People have been arrested defending them and the sweet magnolia, and the huge old London planes. But this is not in the news, because rather than destroying a park they are building a new one, on top of a concrete levee, in order to protect people, which is simply not true. They are doing something. What is it? They are building failure at an enormous cost to life.

One man who lived alongside the park recently jumped out of his 14-story building after throwing his pets out first. I knew him. He led us in yoga during our occupation of City Hall last fall. Did you hear about our occupation? Of course not. Another man in public housing killed his child. There’s no proof that these tragedies are related, but they feel related, and I promise there will be more. That runner was shot 40 years ago, when the park felt abandoned. Can you imagine the feeling in the neighborhood when there is no park? That feeling’s coming. We’re pretty close. No news.

This park, East River Park, only flooded once in 80 years for three hours during Sandy. They are spending almost two billion dollars to solve a three-hour problem. The water that filled the basements of the buildings bordering FDR and the park came from Uptown, where there is no park. The park was protection. The park, we cannot say this enough, is a sponge. A sponge that is being extracted, one branch, one leaf, one root, one squirrel, one mentally ill neighbor at a time.

What’s left? It’s New York. Somebody will have made a lot of money. And the East Side will look like the West Side, will look like Brooklyn, and then, let’s face it, the waters will come. It’ll be like something you never saw before. And it came here first. That’s my New York history.