Nightlife personality Linda Simpson joins Document to discuss the magazine that captured New York’s queer fringe in the ’80s and ’90s—and its triumphant return

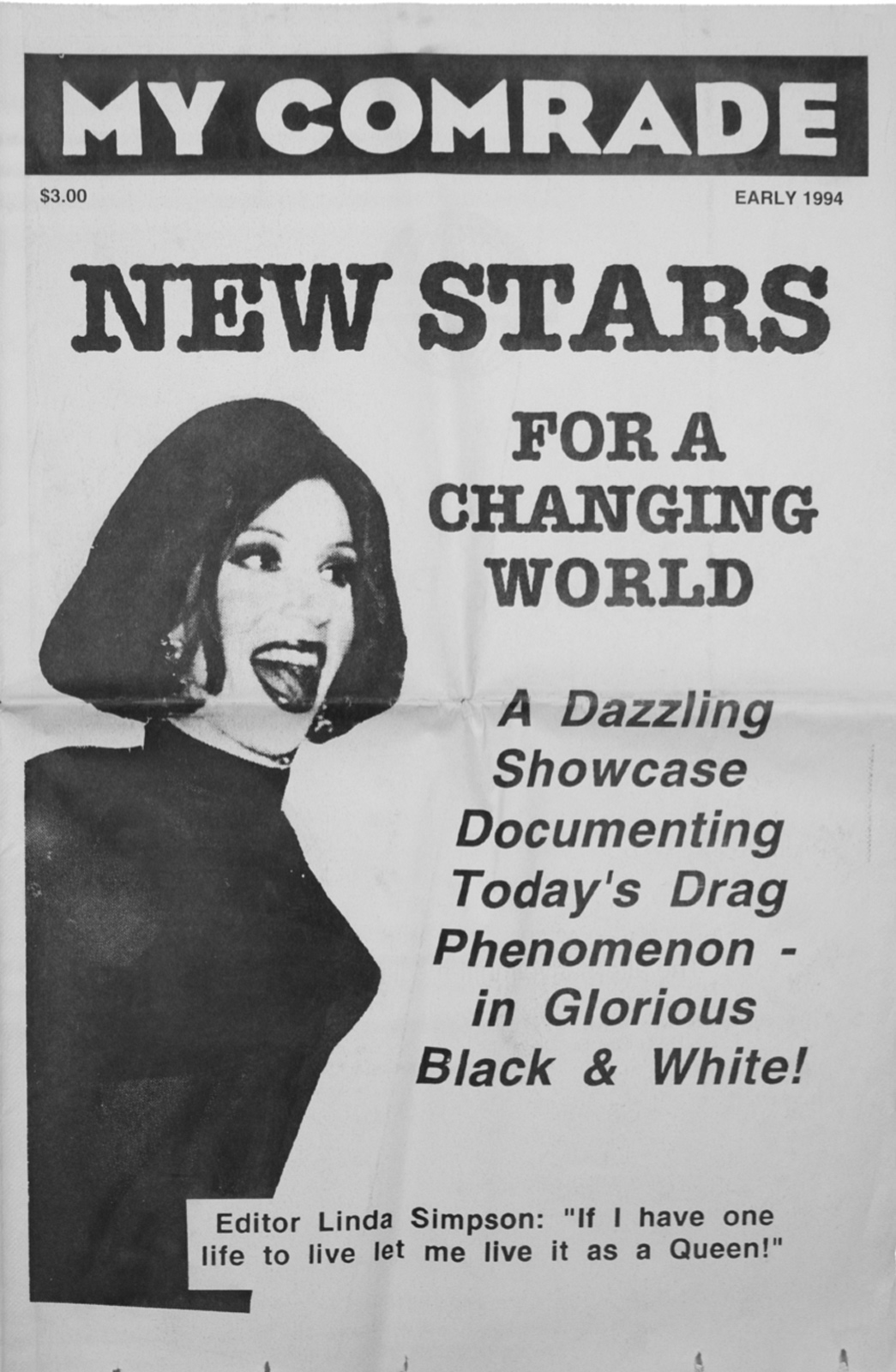

My Comrade is a cultural touchstone for anyone interested in gay history. Founded in 1987 by visual artist and nightlife personality Linda Simpson, the magazine was the revolutionary voice of the East Village’s queer community in the face of the fear associated with the AIDs epidemic.

Throughout the late ’80s and early ’90s, Simpson spotlighted her fellow drag queens, capturing the cultural zeitgeist of New York City’s gay scene thorough an uplifting, defiantly radical lens. This was a magazine made by queer creatives for their own community; it wasn’t watered down to appeal to a mainstream gaze. During the seven years it was in print, My Comrade evolved into what Simpson calls a “celebratory journal of shared experience for NYC’s queer fringe.”

Now, 35 years after she started My Comrade, Simpson has organized an art show that surveys the magazine’s archives along with the first new issue in 16 years. Reproductions and blown-up pages of My Comrade fill the gallery walls, alongside Simpson’s color photos from the same period. Since the show opened, Simpson has hosted various panels and events in the gallery space that bring together old and new admirers alike.

Since it fell out of print in the mid ’90s, the magazine has developed a generation-spanning network of fans, who obsessively collect and share past issues among each other. Musician and performer Macy Rodman, who is the magazine’s latest cover star, knew about My Comrade long before Simpson asked her to grace its cover. “A few years back, my friend Bradford [Nordeen] showed me a big collection of back issues and I was obsessed. It is truly a peek into the New York I always dreamed of before moving here,” she says.

My Comrade is groundbreaking, rebellious, horny, and, most importantly, humorous. Each issue features subversive illustrations, sexy photo spreads, nightlife photos, English and Spanish comic book strips, personal essays, and interviews. Regular contributors included artist Tabboo!, drag queens Lady Bunny, Hapi Phace, and RuPaul, and photographers Jack Pierson and David Armstrong. Like an inside joke for the queer community, many of the features were written with a wink, such as Hapi Phace’s piece “In the Time It Takes You to Read This Article Heterosexuals Will Have Added 1,242 Babies to Our Overcrowded Planet.” Another page features a drawing by Keith Haring advertising safe sex. The magazine also featured Sister!, a section for lesbians that appeared on the flip side.

My Comrade was a DIY project, run by Simpson and a small group of volunteers. “In those early computer days, putting together any sort of publication—especially an underground, black-and-white Xeroxed zine on a shoestring budget—was very labor intensive. Countless hours were spent rubber-cementing artwork and text to layout boards and trekking back and forth to copy stores,” Simpson writes in the catalog that accompanies her recent show. The magazine’s early issues were sold at downtown shops. Later it was distributed nationwide.

While Simpson found financial support from boutiques like Patricia Field, many companies would not advertise in My Comrade due to the stigma around gay magazines. As an alternative means to raise funds and promote the magazine, Simpson would host a weekly night, Channel 69, at NYC’s legendary queer punk nightclub Pyramid Club. She also found a majority of her contributors there.

“As time has passed and drag has solidified itself in popular culture, thanks to the success of the wildly popular show RuPaul’s Drag Race, Simpson’s work has become a window to a pivotal era of underground drag that paved the way for generations to come.”

In many ways, My Comrade was an extension of Simpson’s life and the people who inhabited it. Since the ’80s, she has been a nightlife personality, journalist, photographer, playwright, and game-show host. She currently hosts riotous bingo nights at the Nordstrom department store in Midtown, Brooklyn Brewery, and Gringo’s Tacos in Jersey City.

Before Simpson made a name for herself as an iconic New York drag queen, she grew up reading magazines, poring over pages of cutting-edge fashion, art, music, film, and sexual imagery. She was born in Minnesota to a minister father and housewife mother. Her queer consciousness was formed by magazines like Interview, which she first discovered when Andy Warhol came by her local Barnes & Noble to promote one of his books. She skipped school to see him, and left with budding dreams of New York City, her first copy of the magazine in hand.

She moved to New York in the ’80s to study advertising and communications at New York University before dropping out to immerse herself in queer nightlife. She first experimented with drag one Halloween, but her alter ego Les Simpson wasn’t born until she became involved in downtown Manhattan nightlife. She discovered the drag community and began to develop a career girl persona that toes the line between camp and everyday life.

Although Simpson was constantly working on My Comrade during the late ’80s and early ’90s, the demands of her career as a performer and other creative ventures resulted in a publishing schedule that produced 11 issues from 1987 to 1994, before she became burnt out and put the project on indefinite pause. Following her time publishing My Comrade, Simpson was the LGBTQ+ editor at Time Out New York during the magazine’s glory days. She later revived her magazine in 2004 and 2006 to produce two more issues after a burst of inspiration.

The New York Times once accurately described Simpson as “The Accidental Historian of Drag Queens.” An advocate of living in the now, Simpson famously brought her point-and-shoot camera with her to the gay nightclubs to combat her shyness. She was behind the scenes at Pyramid Club’s dressing room as budding queens RuPaul and Mistress Formika got ready. She was on the dancefloor of infamous clubs Limelight and Palladium snapping shots of club kids like Waltpaper in outrageous glam looks. She was there in the early years of Wigstock, the famed annual drag festival hosted by Lady Bunny in a towering wig at Tompkins Square Park.

Years later, she found herself with an archive of over 5,000 photographs that documented the birth of New York City’s most legendary drag queens. Many of her photos have been published in her acclaimed 2021 photobook The Drag Explosion as well as in documentaries, magazines, and her touring slideshow.

When Simpson began documenting the scene and publishing her magazine, drag was still a subculture and queens eschewed perfectionism in favor of self-expression and experimentation. Drag had yet to adopt the polished, over-the-top glam aesthetic it is known for now. Everything changed in 1992, when RuPaul’s iconic nightlife anthem “Supermodel (You Better Work)” dominated the charts and introduced drag to the mainstream.

As time has passed and drag has solidified itself in popular culture, thanks to the success of the wildly popular show RuPaul’s Drag Race, Simpson’s work has become a window to a pivotal era of underground drag that paved the way for generations to come. Recently, the magazine’s complete archive was acquired by Harvard for its Houghton Library’s literary and performing arts archives.

Simpson was there for the fertile years where drag was still on the fringe and possessed a sense of rawness and grit. She was also there for the drag boom of the early ’90s that catapulted RuPaul and the drag scene as a whole to a new level of stardom. And, as her current exhibition and recent issue of My Comrade proves, she still has her finger on the pulse of today’s scene.

Archival footage of My Comrade serves as a reminder of a simpler time, with Simpson’s most recent issue seamlessly bridging the gap between old and new generations of queer creatives. Here, she joins Document to discuss My Comrade, then and now.

Meka Boyle: What inspired you to create My Comrade?

Linda Simpson: The gay press was just horrible and defeatist back then, so we needed an alternative. Granted, those were terrible times, but I felt like what was needed was kind of like a rallying cry.

Meka: In the catalog for the show, you mention how when you started My Comrade you considered adopting a nihilistic, angry tone before concluding that an inspirational message of love and unity was more empowering. Did you try to at first experiment with different voices?

“Humor gives you power as a way of laughing at things that are used against you or oppressing you. It is a very powerful tool.”

Linda: I wrote something like a letter from the editor in that angry tone. And it’s kind of like when they say, if you have an argument with someone, you should write them a letter and then never send it. I just had to get out my raw emotions and then I realized that maybe this is personally satisfying, but I don’t think it would be of that great an interest or that positive of an influence on anybody else. So I decided to go the other route. It was all pretty organic.

Meka: Was it an intuitive decision to use the cut-and-paste style, along with the comic book illustrations and texts?

Linda: Well, part of that was the mother of necessity that comes with [being] a low budget magazine. But also, I was fascinated by the punk aesthetic, which was very cut-and-paste. The photo novellas were another nod to tabloid culture—I was influenced by what was on the newsstand at the time. I wanted to make it funny, too, so it was uplifting in that regard. Almost everything that we put in the pages had a humorous aspect to it.

Meka: Right, and humor makes difficult conversations more accessible. It adds another layer and gives an entry point for people to share personal experiences and discuss topics that are taboo.

Linda: Exactly. And also, it’s empowering! Humor gives you power as a way of laughing at things that are used against you or oppressing you. It is a very powerful tool. My Comrade was a happy face during dark times. It gave people a feeling of camaraderie, a sense of togetherness.

Meka: You were inspired by reading earlier magazines like Interview and After Dark, but did you have any experience working on a magazine before My Comrade?

Linda: I always appreciated magazines, but I had never tried it myself. I was hanging around like in the late ’80s. I was friendly with this journalist George Wayne, and he used to put out a magazine called R.O.M.E. He did it sort of like a Vanity Fair, but just sort of putting it all together himself and Xeroxing the pages. And I was just inspired by his chutzpah and his DIY attitude. And so I decided to do my own magazine. I kind of had an idea of how magazines worked from having read so many myself and being such a fan. So I knew that it was possible to imitate or emulate bigger publications.

Meka: How did you first discover Interview Magazine?

Linda: I’m from Minnesota, and Interview was difficult to find where I lived, but there were a couple of magazine stores that sold it. But I actually think the first time I saw Interview was when Andy Warhol visited. He was promoting some book, I think it was at Barnes & Noble, and I skipped school and went and saw him. They were handing out copies of Interview and that’s when I got the first one.

Meka: And you have some photos of Andy, too, don’t you?

Linda: I’ve posted some on Instagram. During the ’80s, Andy Warhol was very ubiquitous. So you would see him a lot at events and night clubs and around 14th Street because the factory was on Union Square. I saw him up close and personal, and happened to have my camera.

Meka: Over the years those photos have gained layers of importance because they captured such a pivotal moment in queer history. Were you aware of your role documenting the scene at the time?

Linda: I wasn’t thinking that lofty. I was just kind of doing it at the moment and having fun with it. I didn’t really didn’t think about my photos or the magazine having any long-lasting significance. So it took me a while to realize that, yes, they are time capsules and yes, they do have some weight and importance.

Meka: A lot of iconic performers like Taboo! and Lady Bunny were regular contributors. Did people reach out to you to contribute, or did you find them?

Linda: I reached out to them when I first started the magazine. I wanted to have this activist aspect, but I also wanted to plug into the East Village drag scene, which was very feisty and fun and campy. I wanted to combine that energy with what I was doing with the magazine. Almost everyone that was in the magazine I met through the nightlife one way or the other whether it be from the East Village to the big clubs.

Meka: I’m sure at the time My Comrade also made a big impact on gay people in places that weren’t as progressive or urban as New York.

Linda: Yes, there are actually people that have told me they moved to New York because of My Comrade. I mean, they might have already been thinking about it, but My Comrade solidified their desire to live here because they saw people they wanted to be with, and a community they wanted to be part of.

“I am happy that I was able to experience [a time] when drag was more of an underground sensation.”

Meka: How has the drag scene changed since the era of My Comrade, when it was more underground and alternative?

Linda: It’s a whole new animal! The drag scene now is pretty much motorized by RuPaul’s Drag Race, [which is] now the main factor in the drag world today. Ever since that started, drag has gained a brand new, much more visible life. And it’s all for the good. I am happy that I was able to experience [a time] when drag was more of an underground sensation. However, there’s a lot more work now for lots of people, and so it’s all for the good. You know, it’s better to be celebrated than not!

I think some people think that it must have been so much more fun back then, and probably in some ways it was, but there also weren’t as many opportunities so it was very limited. There was also a lot of misunderstanding about drag, so it had an edge of danger because there were some people that reacted violently towards the people doing it.

Meka: How did you choose who to feature as far as subjects from the magazine’s original inception like Lady Bunny and Taboo!, and more contemporary people like Macy Rodman?

Linda: I didn’t want it to just be old school contributors. I’ve always liked being intergenerational. I knew Macy. I knew of some of the other people that were selected. I was looking for a youthful vibe and a contemporary feel. I knew that getting the magazine out would help expand the audience.

Meka: When you began creating this recent issue, how did you choose Macy Rodman as a cover star? Did you know you were going to feature her from the beginning?

Linda: I thought of Macy a long time ago. She’s fun and she’s got a dynamic quality to her. I also wanted to include the Bushwick scene, and you know, Macy’s a mover and shaker out there. Of course, Macy is trans, and that’s of the moment in some ways—but it wasn’t the main reason that she was chosen. Although now I’m really glad that there’s a trans woman on the cover because there is the shittiest backlash towards trans people right now, so if I can help elevate the trans experience in any way, I’m happy to do so.

Meka: Moving forward, do you have a plan to do another issue of My Comrade, or are you going to sit with what you just created first?

Linda: I have to sit with it for a little bit and see how it goes. But you know, never say never—I don’t think it’s the last one, that’s for sure.

Linda Simpson My Comrade Magazine: Happy 35th Gay Anniversary is currently on view at Howl! Happening through July 17th.