The artist embarked on a ghoulish tour of artists who have passed, emerging with his most thoughtful album to date

For most of those outside of banks and law offices, the days of mandated dress codes are a thing of the past. Companies now like to wear a (sometimes faux) spirit of collaboration among the personalities on their payroll—techie companies boast coders in graphic tees and relaxed fit jeans, and marketing offices are more often made up of micro-influencers in fast fashion than they are of “Don Draper tailored set” types.

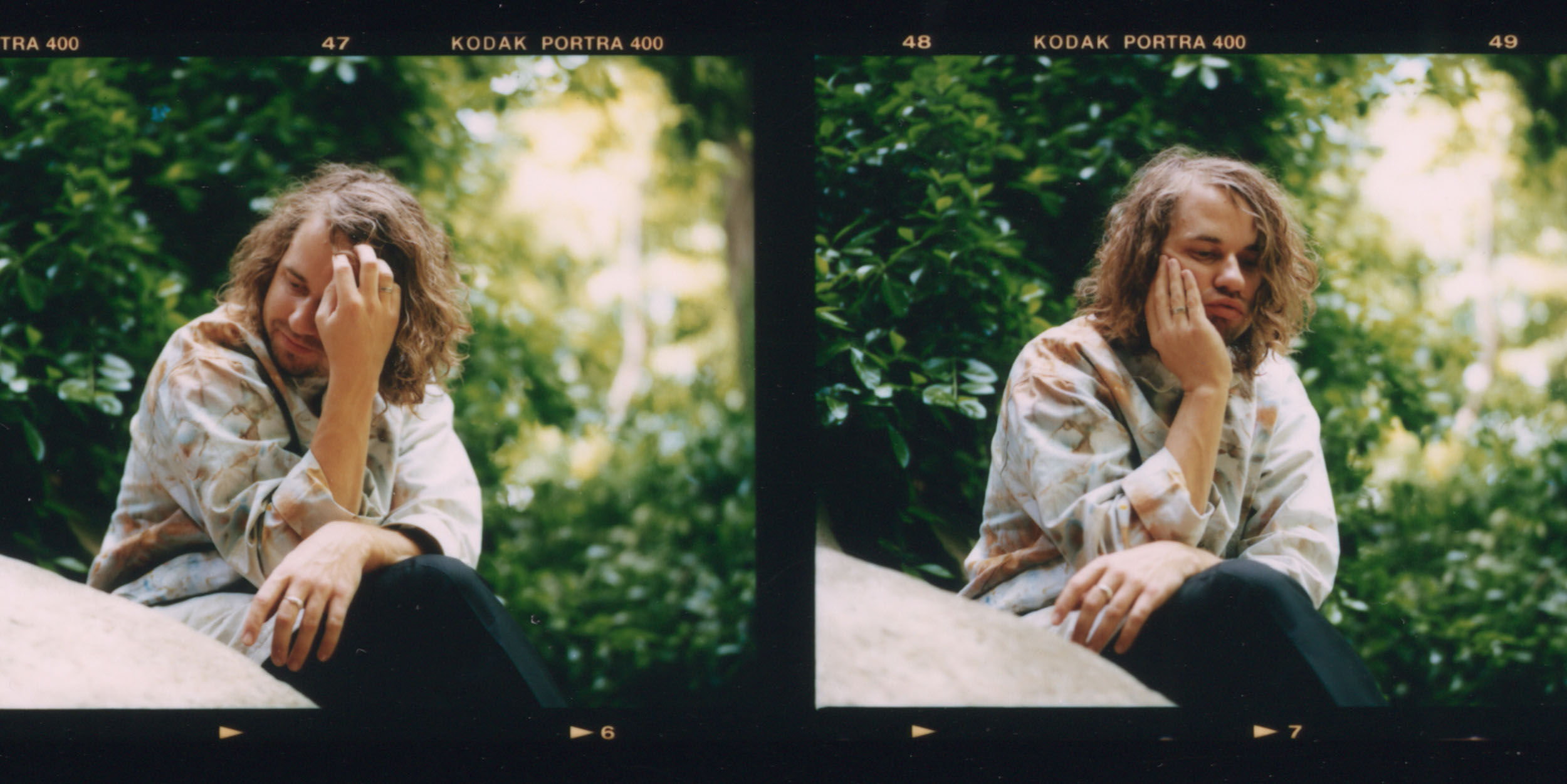

Kevin Morby is one of the few hanging on to the tradition of dressing for work in what would qualify as his Sunday’s best. “There is something I like about putting on the suit to go play, because it feels like, This is my job and this is me taking it seriously,” he explains.

His suits were left to hang in his closet through the pandemic, but he comes out of isolation with an album worthy of their wear. This Is A Photograph, released May 13 via Dead Oceans. The album was born out of a fascination with death, triggered by a family dinner in which his father collapsed onto the table. He survived, but the scare was enough to shock Morby into a state of reorientation in perspective. As he gazed at family photos—his father posing on a lawn, young, shirtless, and prideful—he was reminded of life’s fragility.

Seeking a space to escape from the terrors of the present, Morby sought friends in the past. He moved into Memphis’s Peabody Hotel, Room 409, where he explored a once vibrant city’s ghostly present. He walked to the Mississippi River to visit the spot where Jeff Buckley met his end, to the neighborhood where Jay Reatard spent his last days, and drove through Highway 61 to visit the souls that lovingly haunt it. This Is A Photograph is the product of Morby making death a friend, to play with and learn from.

In celebration of his new album, Morby joined Document to discuss the making of This Is A Photograph, the inherent lineages of music, and the power of a suit.

Megan Hullander: How does it feel to have finished what your publicists have called your ‘magnum opus’?

Kevin Morby: Ha! It feels like a whirlwind. Everything’s feeling really good and really strong. I haven’t done any sort of press, in this manner, since before COVID. It’s an interesting thing, where it feels like I’m doing it for the first time even though I’ve done it before. It’s a strange feeling, but it’s great. I’m feeling very accomplished and I’m very proud of this record.

Megan: If it is your magnum opus, where do you kind of go from there? Like, what’s next?

Kevin: I think I just retire or I start putting some mediocre records and blend into the background. No, it’s funny because I’ve put so much into this record and I feel so strongly about it, and usually when I’m writing albums there’s a companion piece to each record. I’m always writing two at once that are sort of speaking to one another, but this is the first time in my career that I’ve only concentrated on one. It has left me with a little bit of the feeling of ‘Where do I go from here?’ But I’m also not concerned because I’m so busy with everything surrounding this one, so it feels kind of nice to just focus my attention on that. Whatever comes next I think will just naturally reveal itself in time.

When you release something that feels a little bit larger than what you’ve done, it’s kind of nice—not to make something worse, but to make something a little more lowkey. Like, I’m not trying to say too much with this one other than, ‘Here’s some nice songs.’

Megan: You’re fairly prolific in the rate at which you produce work. I think I read that you were worried that it’s going to stop, and that’s what’s fueling your rate of production. Did taking your time with this record change that?

Kevin: I think it did, because it was written during COVID. There was a lot that happened during quarantine, being forced to stop touring and to take a breath and slow down. Even though it was a terrifying time, for the first time in my adult life I was really taking care of myself, my mental and physical health. And it helped me sort of rid myself of the scarcity mentality a little bit. Maybe things can go at a slower pace.

Megan: A fascination with death, maybe only in part fueled by COVID, feels very central to the album. When that manifested was it something that was happening mostly internally, or were you talking about it with everyone you knew and it consumed your whole personality?

Kevin: I think I’ve long had this fascination or desire or need to sing or talk about death. When death is amplified in the way that it was in 2020, when I was writing this record and it was sort of the backdrop to everything that you did in your day-to-day life, where there’s this literal death toll number that everyone is reading everyday, my angle at looking at death became less about ‘Oh this scary thing is going to happen,’ and more, ‘With whatever time we have on this earth, we really need to celebrate it.’

“There’s been a lot of different advances to [music] in terms of technology [but] something I always think about is, everyone’s still playing guitars. What’s a guitar but a piece of fucking wood with six wires on it that makes a sound? It’s actually pretty archaic, and that’s cool.”

Megan: And you did that sort of ghoulish tour of spaces that were meaningful to artists who have passed. You said something to the effect of, ‘The dead can shape the living.’ How much of that do you think is something that’s passive and inevitable, or do you see it as something that requires a conscious engagement from the living?

Kevin: In a lot of cases, it requires seeking it out. I think there’s some stuff that you can’t help you know. Someone like John Lennon or Kurt Cobain’s death, super famous deaths, will shape the living in the way that they’re so embedded in the fabric of culture. But I think for a lot of them—you know, I’ve always been a fan of Patti Smith. I’ve always been inspired by her honoring or worshiping the dead, and seeking out her dead heros, going to their grave sites or visiting their old homes. I think if you seek it out, it can help give your life meaning and shape, and if nothing else it’s just sort of this adventure to go on. It was less about mourning them and more about celebrating what they had once done.

Megan: In what ways did the dead inform this album, and how did you celebrate them? Was it more ideological or aesthetic or thematic?

Kevin: I found the present moment of COVID and what was happening in American politics so horrible and uninspiring that I took this great comfort in the past and sought out these old stories. And while no point in history is without its great complications, these stories were at least not taking place during COVID. It was a nice place to sort of mentally vacation to, and to think about these people, to be in this different time.

Megan: I feel like the nature of storytelling or passing stories down is something that is very central to folk music, which I think this album falls under—like indie-folk in some ways. Folk music, at its heart, is music of a place, and you traversed a very American landscape in creating it. But as we move into a time that decreasingly resonates with Americana and patriotism, how do you think the folk music and the way your music fits into it kind of reflects that?

Kevin: I mean, everything is so different, and it’s constantly changing with advances made by technology and social media, whatever it may be. Indie rock hasn’t been around that long. But kids now, in their teens or early twenties, are making music that, whether they know it or not, is influenced by some of these early pioneers. I find it really interesting that I could see someone who might not know who the Pixies are, but their favorite band was influenced by another band that was influenced by another band that was influenced once by the Pixies. I think that music in general is the greatest example of people borrowing ideas.

Music is so archaic in so many ways, and I think it’ll just always be this place where people are trading and passing ideas back and forth. There’s been a lot of different advances to it in terms of technology. Something I always think about is, everyone’s still playing guitars. I know people like to say that we’re advancing into a time where guitars are going away, and I’m like, ‘I don’t know.’ Kendrick Lamar has a backing band and they’re playing guitars. Harry Styles has guitars in his band. And what’s a guitar but a piece of fucking wood with six wires on it that makes a sound? It’s actually pretty archaic, and that’s cool.

“To be a songwriter, you sort of have to go into a character where you take yourself more seriously than you would if you weren’t writing a song. It allows for me to take more risks and kind of become a different person.”

Megan: I feel like when I was listening to these songs, they each carry a very distinctive emotion or mood. Have you thought about how that might carry over live?

Kevin: Songs live for me, it’s almost like I’m trying to create an album on-stage that’s going to have a good ebb and flow to it. I usually wear certain suits or certain outfits that get me into a character. I like to feel that I am a little bit of a different person when I’m on-stage from who I am in real life. I like that. I like the separation of becoming this new thing.

Megan: What does that character look like for you? Or feel like?

Kevin: It’s funny, because I feel like the character exists for half the set, then the fourth wall comes down and I’m kind of myself. Maybe more a stoic version of myself, a stoic mysterious songwriter guy. And then, like I said, halfway through the set that comes crashing down once I open my mouth.

Megan: Have you been able to maintain that sense of character, that sense of becoming somebody throughout COVID when you’re stuck inside your own walls—or do you not really engage with that character in the songwriting process at all?

Kevin: I engaged with it in the songwriting process a bit, but I definitely wasn’t putting on a suit every day of COVID. There is something I like about putting on the suit to go play because it feels like, This is my job, and this is me taking it seriously. But I think to be a songwriter, you sort of have to go into a character where you take yourself more seriously than you would if you weren’t writing a song. It allows for me to take more risks and kind of become a different person.