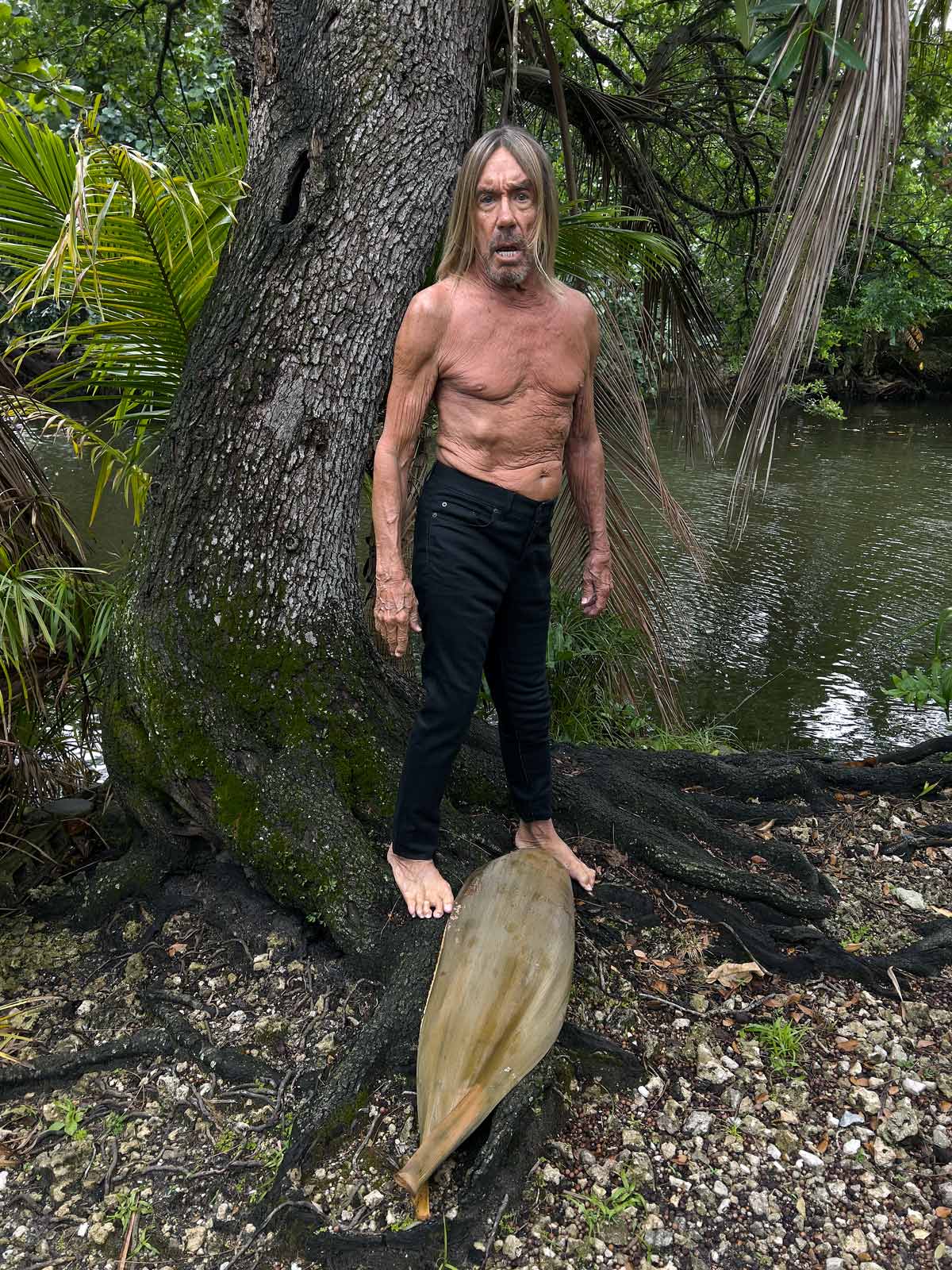

For Document’s Tenth Anniversary issue, the 'Godfather of Punk' and the author-provocateur discuss raging against the machine, weaponizing established paradigms, and leaving New York for greener pastures

“I was wearing my slippers and pajamas, but I knew I was still pretty,” Iggy Pop cackles before lowering his voice back to a snarl, paraphrasing the first chapter of Ottessa Moshfegh’s hit novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation with perverse delight. “Ah, yeah, you know…” he says fondly. “She was siiick.” The book is hardly a portrait of New York City. It takes place almost entirely inside the nameless protagonist’s Upper East Side apartment and the 24-hour Egyptian bodega she trudges to once daily for two coffees and an anesthetized glance at local paper headlines about the Bush vs. Gore election. But Moshfegh’s blonde, thin, model-looking narrator serves as the perfect vessel for the author’s meticulous, visceral account of New York’s pre-9/11 culture: the downtown art scene with “cheap transgressions going for $25,000 a pop,” the blurring of the line between solitude and isolation, self-determination and self-destruction, the existential emptiness of being alive and conscious in a city glimmering with empty sentiment; and, above all, the longing for human connection.

Iggy first arrived in New York with his band The Stooges to record their eponymous debut album. The Stooges was released on August 5, 1969, just 10 days before half a million people would gather on a farm in Bethel, New York for three infamous days of music and peace. The Stooges’s proto-punk anthem “1969”—“Well it’s 1969 okay / All across the USA / It’s another year for me and you / Another year with nothing to do”—encapsulates the “everything sucks, man” attitude that Iggy, an anthropology dropout, found in his Ann Arbor, Michigan bandmates, the Asheton brothers, and made into a radically hopeless art form. “Everything was just so scuzzy and degenerate… It was also welcoming,” he recalls of catching New York at the tail end of both the counterculture movement and Nighthawk culture, the scholar in him mesmerized by the “constantly interesting and clever” band of academic exiles who populated Max’s Kansas City. “The crowd that hung around—the Andy Warhol entourage— a lot of them basically looked like lapsed Kennedys.” (As a teenager, Iggy thought he’d end up in politics—he went door-to-door for John F. Kennedy and got an A+ on his civics paper outlining how he’d seek the presidency at age 45. But he grew disillusioned by the cynicism of public office after Kennedy’s assassination.) Iggy was always a little too ahead of his time to be a superstar on the level of Bob Dylan or David Bowie, but the born antagonist refused to be ignored, selling the poetic lyricism and far-ranging musical influences of The Stooges’s noise with a level of brinkmanship that demanded audience participation. Most audiences were delighted; others didn’t quite know what to do with him. In 2010, Iggy retired from stage-diving after the sport he’s credited with inventing resulted in one too many dislocated shoulders.

Ottessa Moshfegh’s next novel (following Death in Her Hands) examines the social pathologies of our not-so-recent history. Lapvona (to be released in June 2022) takes place in a medieval village, where a shepherd boy’s faith is tested by the rampant greed and corruption of feudal society. Moshfegh’s fascination with the grotesque is translated into exquisite, uncompromising descriptions of drought, disaster, plague, rape, cannibalism, witchcraft, and the bleak realism of class inequality—detailed through the lens of folklore and superstition that her characters use to make sense of the world. It’s something sure to serve the otherworldly ecstasy of the author’s prose. “So much of what I love to write is using conventional systems in order to seduce the reader into a level of comfort so that I can then use the perversity of that against them and change their minds,” she says. Moshfegh wrote Lapnova during the pandemic, and while she doesn’t write with the intention of engaging in a cultural conversation—whether it’s about women, bodies, the meaning of art, or inequality and government corruption—her books do tend to have that effect after they’re published.

Iggy Pop joins Ottessa Moshfegh to discuss raging against the machine, weaponizing established paradigms, and leaving New York for greener pastures.

Iggy Pop: Who are you? I’m Iggy.

Ottessa Moshfegh: Hi. I’m Ottessa.

Iggy: You, I know.

Hannah Ongley: I’m Hannah from Document. I’m hoping to mostly sit in the background and listen to you two speak. It seems like you’re already quite familiar with each other.

Iggy: I’m a reader.

Ottessa: Are you?

Iggy: Well, I’ve read My Year of Rest and Relaxation and your piece in Granta. I had a really beautiful, ancient Kindle that finally died, so it’s slowing me down.

Ottessa: Oh, no.

Hannah: Ottessa, your parents were both scholars of music; and Iggy, yours of literature. There seems to be some sort of interesting upbringing crossover there.

Ottessa: I’m the product of a classical music string players’ romance story that ended.

Iggy: Were you in the school orchestra?

Ottessa: I wasn’t. But my parents—

Iggy: I was.

Ottessa: You were? Did you play the drums?

Iggy: I played timpani in the orchestra, because I didn’t want to play in the marching band. So I told them I was a timpanist because you don’t have to march.

Ottessa: So distinguished, too.

Iggy: It’s a beautiful instrument. School band was fun. It would always be a very upset guy who had to conduct the school band and teach music, and when we’d actually have to go to these recitals they’d always get upset when we made mistakes.

“I knew that I had been gifted with a passion, and that I needed to guard that love of art against anything that came from an institution. But I still knew that my path was to rage against the machine and not to be completely outside of it.”

Ottessa: Did you like having to sit at the back?

Iggy: Well, actually, that was all right. When you play timpani you stand more.

Viola is a beautiful instrument. I read that your mother played one of those.

Ottessa: Yes, she’s a violist and my dad is a violinist. My parents became teachers, so I grew up with screeching violins in the living room. So, I can’t say I really love the sound of a violin. Violin, for me, is this very neurotic, egocentric instrument, and the viola is like the spirit world.

Hannah: Iggy, I read that when you were growing up your parents purchased you a drum kit that got a lot of use in the living room between the hours of after school and the early morning.

Iggy: We lived in a trailer. On both sides of the family, the grandparents were very poor. My parents were a couple of kids who’d been born in fear of poverty and chaos. They were very strict about everything—there was never a curse word, never a drink consumed in the home. But they couldn’t say no to culture. As I became interested in music, the family purchased an American colonial-style stereo that looked like respectable furniture, and I was exposed to Sinatra, Ravel, Debussy, Charlie Barnet—you know, ‘good’ music. Things took a left turn from there. But they were always great about it.

[Ottessa], you have actual degrees, I suppose. I saw you had an MFA. I went to university for one semester, but I’d already had my ‘senior summer’ out of high school. I played drums full-time in a cover band at a teen club, and I got hooked on the life. I went to college and wandered around for a semester seeing these professors who didn’t know how to speak giving lectures, [who] couldn’t wait to get out of class and had to teach us something. So I dropped out, and I decided, I’m going to do music.

Hannah: It sounds like your music career was almost a study in anthropology. It’s like, ‘Okay, I’ve done this. Now what?’

Iggy: Yeah, I really liked ANTH101. I had a card for the library, and that was very important. My music career started by using the university in an alternative way, as a lot of people do. I was thinking about that, Ottessa, when I read that you went to school at Barnard and you were from Newton. There are a lot of people who—they’re not students, and they’re not townies, but they hang around the campus and live like students. In Ann Arbor, a lot of these people were musicians and musical people, so I jumped in with them and they started upgrading my tastes in music and then pleasure seeking.

Ottessa: I had my first experiences of ecstasy as a pianist playing Chopin concertos—the ecstasy in art always had a very strong relationship with self-discipline and suffering. Chasing the dragon of absolute bliss beyond the world came only when I had enough proficiency and facility to do it with this bullshit human body, and there was God in that. But I decided not to pursue music when I discovered writing. I think partly it was because I was from, like you said, the places where intellectual institutions were like church—the highest level of human accomplishment is through using your mind in these ways that have been passed down through history.

I had two things going for me: I wanted desperately to get out of the house I grew up in; second, I knew that I had been gifted with a passion, and that I needed to guard that love of art against anything that came from an institution. But I still knew that my path was to rage against the machine and not to be completely outside of it.

So much of what I love to write is using conventional systems in order to seduce the reader into a level of comfort so that I can then use the perversity of that against them and change their minds. Sort of like that martial art, aikido, where you’re using circular movement to use your opponent’s power against them. Maybe it’s because I grew up with classical music and have this respect for established paradigms, and also see the power of it because it provides immediate access to a reader [for them] to be like, ‘Oh, this is familiar. I can relax.’ And now, within that familiar paradigm, I can do something new.

Hannah: That sounds a lot like how you would interact with an audience on stage, in terms of challenging them.

Iggy: Well, these are the same things. Ottessa is saying that you can challenge, and you can do something that, if you show it, is already very strong within you. But if you don’t seduce [the audience], and you fail to entertain them, you’re fucked. You have to take a cold look at what motivates them, and what they will react to. Most of those things you know instinctively, you don’t need to learn. We learn those things from the time we’re about five and start interacting with other little brats. I think it’s probably different for someone who actually makes a living playing Chopin, who goes the other way and decides not to write, not to be the author themselves. Those people can pretty much pour everything into that vessel, but they don’t have to go so far. When you author the stuff, and you’re really laying yourself out there, there’s always the possibility of being ignored or rejected.

“If you don’t seduce [the audience], and you fail to entertain them, you’re fucked. You have to take a cold look at what motivates them, and what they will react to. Most of those things you know instinctively, you don’t need to learn.”

Hannah: Iggy, you have spoken about William Burroughs’s method of ‘cut up’ as a practice of assembling a piece of work. It reminded me of something that Ottessa said in an interview in The Guardian about writing Eileen using a how-to guide as an Oulipian thing, in terms of the structure of a commercial novel.

Iggy: I don’t think William Burroughs ever wrote a novel with, say, the full structure of what Ottessa can do. That was pushed at him as a criticism once by Martin Amis, who said, ‘He’s just a great writer of bits.’ On the other hand, his bits—whoa. You look at some of his middle-period stuff and he was writing about Middle Eastern assassination systems: Hassan-i Sabbah, who would send assassins to all his enemies all over the Middle East, promising them paradise if they killed the enemy. Sound familiar? He had a piece more toward the end, he talked about, ‘Hey, anybody could build a border, do-it-yourself borders. You could put up a shack, you could put up a gate, and a sign.’ [Laughs] And now we’re seeing that in all the contested territories around the world.

The only thing that I ever read from him that approached a full narrative was Junkie. I picked it up because at the time I was a junkie. I might have been somebody who felt overweight and picked up a self-help book [laughs]. But it was a beautifully written, poignant book. It was mostly a portrait of a guy named Hubert Humphrey, who actually existed on the Lower East Side, but there are beautiful scenes in there that would take place at the Times Square Walgreens counter at two in the morning in a New York that’s gone but that I’m just old enough to remember—I caught the tail end of Nighthawk culture in the US. I don’t think he had the patience to actually put together a narrative where you turn the page and you go through the steps. But it still rings a bell in the wider area of what’s good and bad, what’s going on in this culture now. That’s hard to do. That’s what I liked about [My Year of Rest and Relaxation]. And obviously I could relate—I’d lived in New York 20 years, so I enjoyed the description of the inside of the freezer at the Egyptian bodega and how horrible it was. [Laughs] You know, Arghh! There’s a lot that’s presented in a way that I could have a laugh about it, but it’s not funny either.

Did you stay [in New York] a while, Ottessa? You must have.

Ottessa: I moved to New York when I was 17 and I was there for a span of 10 years. But I took a couple of years to live in China. I lived in Wuhan, actually, which was fascinating and awesome and super gritty and totally chaotic to me.

Iggy: What was the bar like? The bar that you worked at.

Ottessa: It was on the second floor of this building on a boulevard, not really in the center of town—you had to take a bus. There was this big space with windows on one wall and a hole in the ground around the corner where you could piss. And it had a stage. I mostly tended bar.

Iggy: Who was there? What were they doing there? Were they youngsters trying to hurt themselves? [Laughs] What was going on? Was the music live?

Ottessa: It turned out, having no knowledge of this before I moved to Wuhan, that Wuhan was one of just a handful of cities in China where there was an actual punk scene—people, musicians, who were calling themselves punk. I had worked with this guy who was Chinese and from Wuhan who was booking the bands. They were mostly from around Wuhan, then we got some coming from the Southwest, where there was a really big music scene, some bands from Beijing. Some of the bands that were younger were just playing British punk songs and they were singing in English. Others were more invested in being creative and having their own identity. My favorite bands were the ones who were really angry and singing in Chinese… A lot of people wouldn’t know what Wuhan is like. We think of China, we think of Beijing and Shanghai—these very buttoned-up cities—and Wuhan is this enormous metropolis where the distance from the capital has allowed people to be a little bit less controlled.

Iggy: They could be weird.

Ottessa: They could be weird.

Hannah: Do you still follow any of the bands that were playing at the bar?

Ottessa: No. It was weird—I have this piece of my personality that when I say goodbye to something, I just never go back. It took me 10 years of having an iPhone to start using the camera. In general, in life, I feel like I’m just passing through, and I don’t want to get too attached. I kind of let life wash over me, and the places that I do attach [to] are really, in this indirect way, through my fiction. I haven’t been back to Wuhan. I have maybe two friends I still know who knew me then.

Iggy: Where’s this place where you are now? Nice old ceiling in the room.

Ottessa: I’m in Pasadena, California, where it is raining. I live in an unusual house, actually. It was built by this one guy. It took him 20 years, he did it all by hand, and he used all this recycled material including all these stones he took from a church that had been destroyed in an earthquake. So you walk in and it feels a little bit like you’re in a church that’s been destroyed by an earthquake. Where are you?

Iggy: I’m in a village called El Portal, which is on the edge of Miami. I’ve had this [house] since 2004. I’ve been in Miami since ’95.

“I kind of let life wash over me, and the places that I do attach [to] are really, in this indirect way, through my fiction.”

Ottessa: I have to say, Iggy, you’re in one of my top 10 movies of all time, which is Dead Man. That movie is so fucking influential to me, I’ve probably seen it a hundred times. I think Jim [Jarmusch] is amazing. How did the documentary come about? I watched it yesterday, and it makes sense to me now, thinking about you as a performer, the kind of generosity that it takes to really tell your story and go back there.

Iggy: Well, I’d worked with him a little bit. The first time it was Coffee and Cigarettes and, at the time, it was a series of shorts that were supposed to be made for MTV. He’s really in control when you first enter a project of his. He’s very tall timber. Like the old guys who would get to either direct a film or be the pilot of a commercial airliner or the CEO of a blue chip company. This is a certain American Classic guy who doesn’t waste his words. He was shooting a video for Tom Waits. Jim said, ‘Okay, on our extra time, since we’ve got all this stuff here, we’re going to do a Coffee and Cigarettes episode with Iggy.’ And Tom said, ‘Oh, okay.’ He gave us a script at midnight, the night before a 6 a.m. shoot. I get the script, I go home to the Best Western in wherever Wine Country—because Jim always puts you in the cheapest motel possible—and I’m reading the script, and it’s all digs about my name and stuff like that, and Tom looks insulted and he doesn’t know what to do. We get there in the morning and Tom says, ‘Well, Jim, you tell me where the laughs are in this thing because I don’t see any.’ But we did it, and we got along fine. Then, of course, in Dead Man, he says, ‘Great, you’re playing the mother figure.’ [Laughs] I still have the bonnet, in this house, that I wore in Dead Man.

Years later, when I felt people wanted to do something on The Stooges, I thought we were worth it. That band meant the world to me. So I asked him. He’s from Ohio, not so far from Michigan. You don’t give a proposal to this guy, or have somebody call somebody, you don’t bug him about it. I just said, ‘Jim, would you make a movie about my band?’ He waited, I think it was a good six months, before he said, ‘Well, okay, I could make a movie about your band, we’d have to get some money for that.’ He made a little proposal and he mailed it to me. He said, ‘It’s alright with you?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, that sounds alright with me.’ A couple years went by, then I got this phone call and he said, ‘Well, we’ve got a couple guys. They’re from South America and I don’t know where the money comes from, but they’re Stooge fans. And they want to do it.’

Finally, one day I got the movie. And I thought, This is very good. This is right. I was rewarded for my audacity and good taste, because the band was interesting and of quality. There wasn’t a lot to work with, because not everybody was alive. With so many of these music films, there are two or three or four companies that churn them out, and they get in league with the agent and the manager and the company that’s going to put out the accompanying new release—there was none of that in this. It was just about this dead band. It was a great gift from Jim.

Ottessa: I just so enjoyed watching that documentary because I could binge on your performances.

Iggy: We went with the idea of what it should be. We were never going for, ‘Okay, well, if we do this, because everybody else is doing this and things work this way, we will get to a point B.’ Everybody in that group had a dream in some way. The original guitar player quit his senior year of high school, and his friend—who was the original bass player—sold a motorcycle, and they flew to Liverpool to meet The Beatles. Who else would do that? [Laughs] They didn’t meet The Beatles, but they saw some of the [other] groups play. And me, I had a dream. I didn’t even realize it. But when my father was near the end, he took my hand and he said, ‘Well, you made your dream come true.’ Which is not at all how that feels now, or how life is ever going to feel, but still. You set out to do some sort of vocation and you want to have a decent career.

Ottessa: I watched Gimme Danger yesterday and one thing that really strikes me is it sounds like you had really great parents—and how important it is for an artist to be supported in that essential way, and how easy it is to fuck up a kid. It makes total sense to me that so many of our most beautiful artists self-destruct, because it takes so much strength, courage, self-motivation to continue and persist to be innovative, not—like you were saying—get into what other people are doing. I don’t know if it’s worse or better now, but I can’t even read my contemporaries. I can’t be on social media. It’s a tricky balance to stay authentic, and the way that you did that is so inspiring to me.

Iggy: I feel the same toward you, Ottessa.

Ottessa: Thank you.

Grooming Mariana Pineda. Stylist Assistant James Kelley. Tailor Lars Nord. Production Ms4 Production. Post Production Catalin Plesa at Quickfix Retouch.