The exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art paints a picture of modernity that honors antiquity

“Artists are inspired by, and draw upon, sources across time, geography, and cultures,” reads a placard on the wall at Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity. “There is a cyclical nature to the way inspiration and creativity flow; sometimes ideas evolve and other times there are transcendent shifts.”

The show opened on Saturday at the Dallas Museum of Art. It contains over 400 pieces—jewelry of all sorts, manuscripts, tapestries, and various luxury objects—housed within a custom-made exhibition space by renowned architecture studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro. DMA is the sole North American venue for Cartier and Islamic Art, and the second overall, following its presentation at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris this winter.

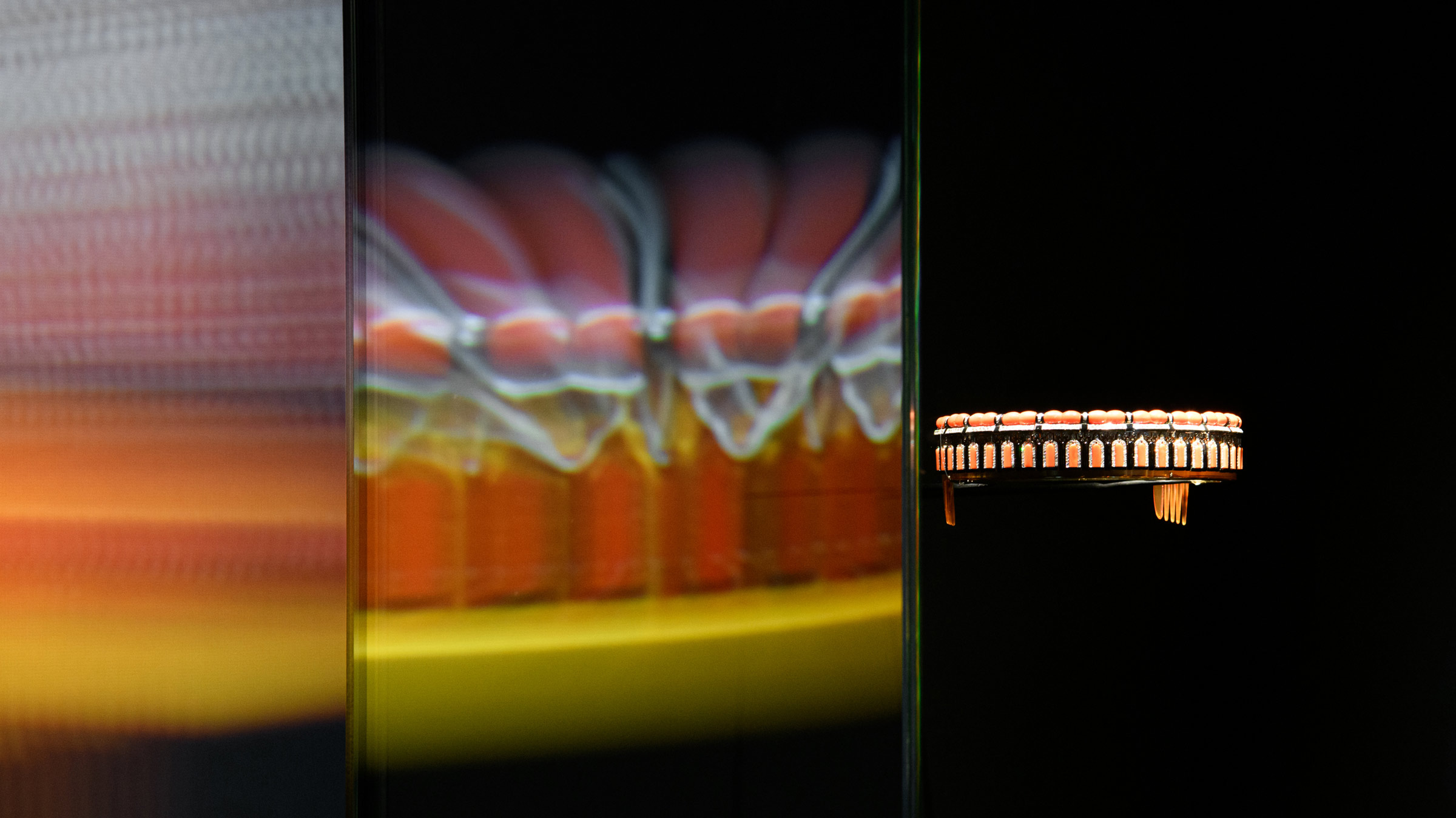

The show marks a return to tactility, commented co-curator Sarah Schleuning during a panel discussion prior to its opening. It was difficult, she explained, to imagine an exhibition centered around jewelry amidst the pandemic—an art form that’s meant to be touched, to be gazed at closely, to drape across the body. Diligent collaboration with the space’s designers was required to bring the physicality of the pieces to life. This meant integrating technology: One of the show’s most engaging components is its large-scale animations, which demonstrate the ties between traditional Islamic architecture and Cartier art objects, which are displayed closeby. Gemstones take on the shapes of archways and columns—the piece of jewelry is gradually assembled on-screen, becoming a literate reflection of the built landscape that inspired it.

The collection is more than a simple display of notable pieces, though that would be impressive in its own right. It traces, rather, the influence of Islamic art on Cartier in the late 19th and early 20th century, as Paris gained interest in Eastern aesthetics. Louis Cartier, the house’s founder, amassed his own collection of Persian and Indian art, which inspired jewelry lines that adopted Islamic motifs, geometry, colors, and materials. Cartier’s iconic Tutti Frutti collection, for instance, was inspired by the leaf-shaped cuts that originated in the time of Mughal India.

The exhibition is multidimensional, sourced from several institutions—Cartier’s own holdings, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, the Louvre, the Keir Collection of Islamic art. But it comes together to paint a picture of ‘modernity’ as Louis Cartier independently understood it: modernity that doesn’t aim to forget the past, or move beyond it. Cartier constructed the future of design by taking the finest elements of antiquity, and moving forward from there.

“For over a century, Cartier and its designers have recognized and celebrated the inherent beauty and symbolic values found in Islamic art and architecture, weaving similar elements into their own designs,” said Dr. Agustín Arteaga, Eugene McDermott Director at the museum. “This bridging of Eastern and Western art forms speaks exactly to the kinds of cross-cultural connections that the DMA is committed to highlighting.”

Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art through September 18.