Even in environments that encourage us to question systemic norms, discussions around labor practices are often met with resistance

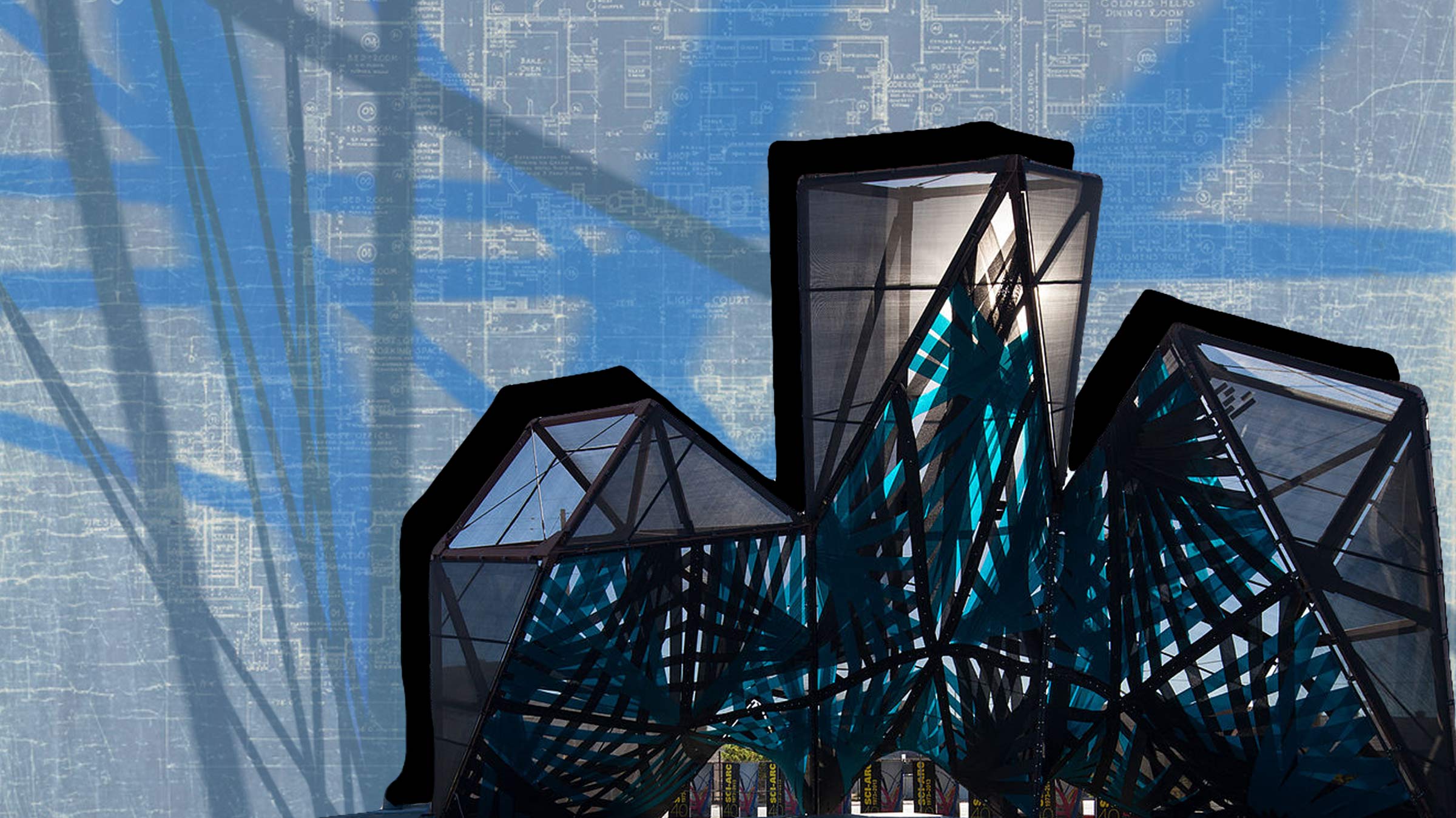

On March 25, the Southern California Institute of Architecture, commonly known as SCI-Arc, live-streamed a roundtable discussion between faculty and students, titled “How to be in an Office.”

Taken from the university’s website: “SCI-Arc was founded in 1972 by a group of faculty and students who wanted to approach the subject of architecture from a more experimental perspective than what was being offered by traditional institutions at the time.” This is to say that SCI-Arc has a reputation for doing things differently, in terms of what’s taught, how it’s taught, and who’s teaching.

Many of the school’s faculty members, including panelists Dwayne Oyler and Margaret Griffin, have their own architecture firms, so it comes as no surprise that the roundtable felt more like a recruiting pitch for students to work at smaller, more conceptual studios—aspirationally branded as “ateliers”—as opposed to larger offices that are more likely to offer a livable wage at the cost of creative freedom. Though left unsaid, the implied inferiority of “selling out” was obvious.

Making the very real choice between a large firm and a small studio was a theme throughout the discussion. “Is it, like, a 40-hour work week that you can barely get through? Or is it a 60-hour work week that you can’t wait to start every day?” asked Marikka Trotter, the school’s history and theory coordinator. She later asked rhetorically, “Will you feel like you’re living a passionate and fulfilled life [if you commit to a small firm], and you’re working hard for something that matters to you? And not something that only matters to some faceless, nameless, late-capitalist corporation? Yes.” The appeal to a shared disdain for corporate structure and “late capitalism,” in order to sway students to consider internships that pay $500 monthly, felt grossly manipulative.

During the discussion, Griffin mentioned that her daughter, who works in STEM, opted for a lower salary at a smaller company where she’d have more agency. It’s a false equivalence: In STEM and other non-creative industries, you’re rarely in a position where you must choose between a rewarding role and a livable wage. For architecture students, the choice isn’t made on the same terms.

“The talk, and the resulting backlash, revealed an ideological gap between those in power in creative fields, and those hoping to enter them.”

When students were given the chance to ask questions, they brought up the industry’s low salaries and lack of work-life balance. Not only did the panelists fail to propose potential changes within the field, they couldn’t acknowledge the system’s flaws in the first place, going as far as rejecting the term “system” altogether. Their responses were patronizing: With this education, you can always do something else. It was an unintentionally bold statement, coming from an institution with the noble mission of helping “shape the future of the architectural profession.” The talk was most disturbing when it doubled down, labeling the choice between creative, fulfilling work and financial security as an unquestionable—and therefore unchangeable—circumstance.

In the days following the discussion, individuals affiliated with SCI-Arc revealed that students sometimes lost academic scholarships if they refused to work for faculty as interns. When students resigned en masse from an internship with Tom Wiscombe Architects—Wiscombe is the school’s undergraduate chair—after being asked to deep clean the studio, Trotter, who works for Wiscombe’s firm, allegedly told students they might ruin their reputations with such a move. On March 30, SCI-Arc’s director and CEO placed Wiscombe and Trotter on administrative leave.

The talk, and the resulting backlash, revealed an ideological gap between those in power in creative fields, and those hoping to enter them. There is a tension between the two groups: One says, “Figure it out within the realities of the current system,” and the other responds, “No, let’s try to change that system.” Students aren’t saying that the pay at small, creative firms should be equal to that of corporate firms, or careers outside of the creative realm. They are saying that they should be able to pursue a creative career while earning a livable wage, without having to rely on side hustles—it’s a term the panel often leaned on when faced with difficult questions. (Granted, when Oyler acknowledged that paying for college has gotten much harder, he was visibly uncomfortable when “several side hustles” was Griffin’s suggested solution.)

Even in environments that encourage us to question norms and imagine possible futures, idealism is often met with resistance. The situation at SCI-Arc exposes the massive distance between youth consensus and voices of authority, and asks us to consider the broader implications of this difference in schools, in creative industries, and in the pursuit of a rewarding life.