The duo joins Document to discuss their new album ‘Two Ribbons,’ dissect their relationship, and attempt to normalize berry picking in graveyards

Let’s Eat Grandma may have actually eaten your grandma, or someone’s grandma, or, rather, something that might have grown out of or nearby someone’s grandma. Rosa Walton and her mother used to pick blackberries that grew around the graves at a local cemetery. That cemetery lies between Walton’s home and the home of Jenny Hollingsworth, and served as a site of contemplation for the duo as they created their third album, Two Ribbons.

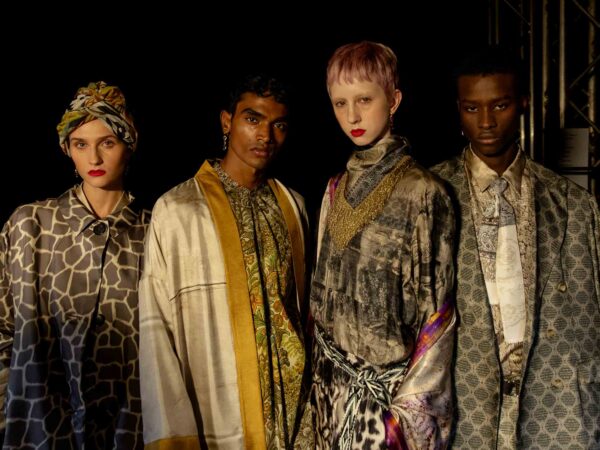

On their first album, I, Gemini, the two positioned themselves as twins. Hair interwoven, speaking in unison, and practically telepathic, their twinship felt more real than if they had actually been born from the same person at the same time. Friends since early childhood and musical collaborators since 13 (the brink of identity forming), their relationship was all-consuming. Nearly 10 years later, Two Ribbons sees the duo emerge as individuals, with Walton and Hollingsworth each taking ownership of their identities and, consequently, their songs.

In the years over which this album manifested, the girls that make up Let’s Eat Grandma each encountered experiences that necessitated personal growth. In her writing, Hollingsworth needed to address her relationship with Billy Clayton, an artist whose music massively influenced her, and with whom she developed a romantic love, which was cut short when he tragically lost his battle with a rare form of blood cancer. Her songs on the record refract and reflect that relationship, allowing her to reclaim control amidst life’s chaos. At the same time, Walton journeyed to London, eager to forge her own path after a breakup with her first love and a natural, perhaps healthy, distance growing between her and Hollingsworth. Her songs traverse new worlds, both internal and external; “The moment in time where our shadows collided and I told the truth, you linked through my fingers and followed me into the hall of mirrors.”

Hollingsworth and Walton join Document to reflect on Two Ribbons, which was released today, dissect their relationship, and attempt to normalize berry picking in graveyards.

Megan Hullander: I wouldn’t say that you’ve grown apart necessarily, but it’s clear you’re both grown separately, as individuals, on this album. How did those conversations around getting that distance from each other start?

Jenny Hollingsworth: I actually think that those conversations are something that we had through the songs. The songs were our way of communicating the way that we’re growing into individuals and all these things, when we weren’t really able to have conversations about it. A lot of the album is about our struggle to communicate those things and not really having clear answers on it.

Rosa Walton: Those realizations also came through the songs. At the time, I think it was very clear that we were having difficulties between each other, but not necessarily the reasons why. I think some of the songs and the process of writing the songs revealed some of those things.

“The songs were our way of communicating the way that we’re growing into individuals and all these things, when we weren’t really able to have conversations about it.”

Megan: And as the songs are more so each your own than belonging to the both of you, what do you think the connective thread between them is that makes them an album rather than just a collection of songs?

Rosa: It’s surprising how cohesive it naturally was, considering we wrote separately. For example, the fact that we’ve sort of grown up writing songs together, I think we have developed this style—like, being inspired by each other and bouncing off each other. That kind of happens naturally when we’re writing. We found that we even use some of the same images a lot, but in different ways. At the end, we could see all these parallels, like we both talked about winged creatures a lot, whether it was butterflies or insects or birds. I think we both talked about waves and the symbolism of those images. I guess the obvious one with the winged creatures is some sort of freedom or escaping.

Jenny: I think some of that is probably because, again, we’ve learned to write together, but I also think even though we’ve both been through different things over the process of writing this record, we’re still very much in the same environment. We’re both from Norwich, we see the same landscapes, we are into a lot of similar things. Even if we have gone through slightly different experiences, we’re both in each other’s lives. We both still come from a close viewpoint, even if we are quite different in many ways.

Rosa: I think creatively, we’re very aligned in what imagery and things we like, even if it’s listening to other people’s music, and hearing a lyric. The likelihood is that if I like it, Jenny will also like it.

Megan: And when you decided to write more separately, was it ever a question of whether you’d break fully and each make your own records?

Rosa: We were in no doubt that we were making the record together. That was something that I don’t think either of us questioned, that this was the project that we’re working towards.

Megan: I was watching an interview the two of you did five years ago, and it was really sweet. Whoever was speaking would look at the other one of you, as the other looked at the interviewer, and then you’d swap. You’ve been creating music together since you were 13–how has your relationship evolved?

Rosa: I think we did that quite a lot in social situations, or even in work situations. Like if it was Jenny and I and then like someone else, the way that we would converse, we’d be constantly bouncing things off one another. We were like a team of one person, always. I think that obviously comes from the closeness, and also just feeling stronger when you’re with someone else. I think we’re definitely both more independent now.

Jenny: I think we needed to sort of navigate the world as a unit, especially because we started the band so young. We were often in a lot of environments full of adults when we were still kids, really. And also under quite a lot of pressure, I guess. I think that was quite difficult to deal with. I think, partly because you’re still developing as a person. I mean, you do throughout your whole life, but especially when you’re like 13, going until your 20s. You’re not really a fully-realized person yet in terms of your identity. It was just a way of us dealing with it. And also, we were just incredibly close. We’re close now, but we couldn’t keep that going forever.

Rosa: I don’t think it will be healthy. We used to be making jokes about literally everything, like I think humor was another one. It was always like something else to hide behind in those situations where it’d be the two of us and producer or an interviewer or whatever it was.

Jenny: We’d often say things at the same time and have loads of inside jokes. It was almost as if we were entertaining ourselves, to be honest.

Rosa: People used to find us crazy. Maybe we’ve reigned it in a little bit.

Jenny: I think we’re still like that, but maybe we’ve managed to control it.

Megan: It makes me think of the way the two of you wove your hair together, sort of symbolically becoming one person. Where do you think that space from each other has allowed each of you to evolve?

Rosa: Well, Jenny’s got a fringe now.

Jenny: I remember I got my hair cut quite a lot shorter. And this was when we’re still doing the twin thing. It was almost like an attempt to break free, but then I ended up growing it back out again. I think me and Rosa’s personal styles have actually changed quite a lot in the last few years. You know, they’ve always been a bit different, actually. But we used to kind of find a middle ground and dress like that.

I found it oddly empowering getting my fringe cut, which sounds so stupid. I think maybe it just represents you entering a new chapter in your life. Which is hilarious, because when people have a really bad breakup, they do that. I had to wait quite a while after these dramatic life changes to actually get my fringe cut, because I didn’t want to look like I was having some sort of breakdown.

Megan: There’s a lot of range on the album in terms of the sound and the kind of emotions that it brings you through. Where did you each experiment with sound the most?

Jenny: I think Rosa got very into perfecting her production skills. And working on perfecting pop, maybe. For me, I’ve kind of got into a few different styles of music. I’ve been quite into my early ’70s folk stuff and things like that

Rosa: I find it really difficult to pinpoint specific artists as influences. I think that’s quite a deliberate thing as well, not to take direct influence from anybody. To me, it would just end up as a worse version of the original artist.

Megan: Were there any spaces, like, actual physical places in particular, that you associate strongly with this album?

Rosa: I feel like the cemetery, which is in between Jenny’s house and my parents’ house, where both of us went for walks every day for really long periods of time and very rarely bumped into each other. I think a lot of the songs that were written around that time are really associated with the imagery. It’s a really beautiful cemetery with massive trees and flowers, and I’d often walk around whilst listening to some of the tracks, almost as a way of testing it out.

Jenny: I honestly think I probably went, maybe not every day, but at least multiple times a week for about a year and a half. I still go quite often. You’re seeing the same kind of trees, and how they change over time. I think that sort of ties in, for me, to a lot of seasons imagery and the idea of something being really static and still and not changing. You’ve got one small one space, and the details of how the weather is, and what emotional state you’re going through sort of changes it. Weirdly enough, I can hear that in some of the songs.

“I think that the cemetery is quite a liminal space. And it’s also one of the only spaces where it’s socially acceptable to grieve. When you’ve got this juxtaposition between all the graves and all this amazing nature, that’s very much living, it’s quite interesting.”

Rosa: It’s almost like the record spans quite an expanse of time, and how we deal with our relationship changes, and loss and all these things, and how that develops.

Jenny: It’s really cool how whatever season it is, the song has been written and really seeps into the sound of the song. That’s something that maybe I didn’t notice as much at the time, but we’ve really picked up on since listening back. We’re both really influenced by our environment in more ways than we’re even aware of.

Megan: I think the pandemic was sort of ripe with morbid reflection, and forced a lot of people to confront mortality, and it seems like you both ran into that head-on in choosing a cemetery as your space of reflection. Was that intentional? Or has it been a place you’ve always turned to?

Rosa: I used to go blackberry picking there with my mom when I was a kid, and make blackberry jam.

Megan: You’d pick blackberries at the cemetery? Do they grow out of…?

Rosa: They grow around the graves.

Jenny: It’s really amazing. Actually, there’s loads of muntjac deer there as well, things like that. It’s quite amazing nature going on in there.

Rosa: I think I’ve not been to a better cemetery. I have been to loads of cemeteries in London, and there’s obviously some really incredible ones. But there’s just something really special about it.

Jenny: It was always a place that we went to as kids, but I feel like it just took on new meaning. I think it’s also a place where it’s weird talking about the stillness, actually, because it’s almost like—especially if you’re grieving or whatever—it feels like every other space. A lot of life when you’re outside of it feels like life just sort of goes on at full pace. Obviously, there was the pandemic, but in a way, it still felt like that. People don’t really want to talk about or think about death or anything like that, because it freaks people out. It’s a very primal human fear. And I feel like it makes people uncomfortable. And also, life is always rushing on at such a pace, it kind of feels like there’s not really space to grieve sometimes. I think that the cemetery is quite a liminal space. And it’s also one of the only spaces where it’s socially acceptable to grieve. When you’ve got this juxtaposition between all the graves and all this amazing nature, that’s very much living, it’s quite interesting.

I guess it’s a place that I still find very comforting. Which is so weird because I think a lot of people view that as quite morbid, but I think that more shows how uncomfortable death is as a subject for most people in our culture. I actually think there’s a lot of things to learn about life by being more comfortable talking about death.