In his new performance ‘Live From Blackalachia,’ the musician and poet challenges misconceptions of the region and celebrates his relationship to the earth it was filmed on

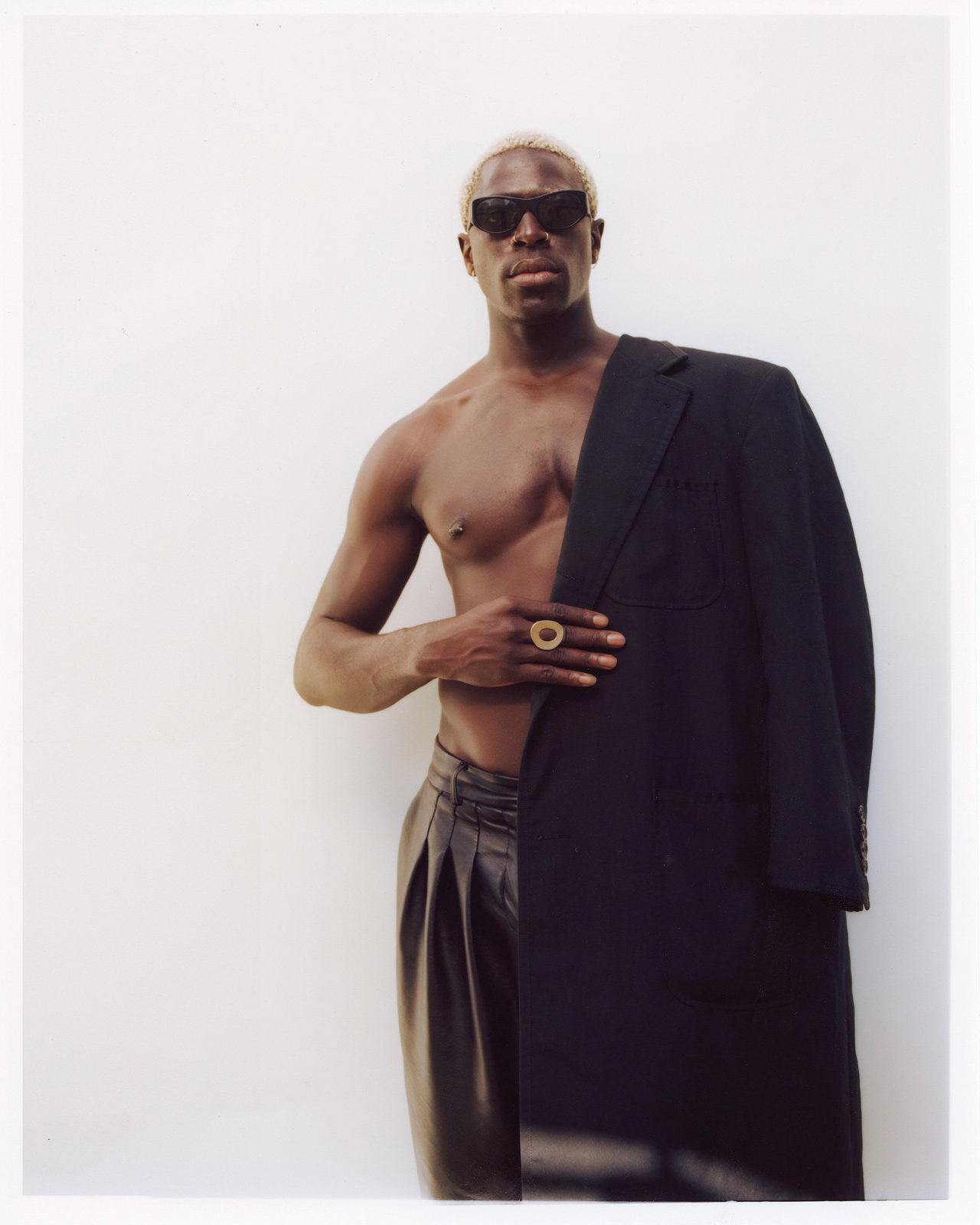

Few people with a spotlight use it to illuminate the many gradations of Appalachia’s geography—but if there’s anyone who would give consideration to an often misconstrued region, it’s Moses Sumney. For nearly a decade, Sumney has fought to stave off the oversimplification of labels and genre, pursuing a multifaceted creative practice that has made him a darling to many realms including art, music, and fashion.

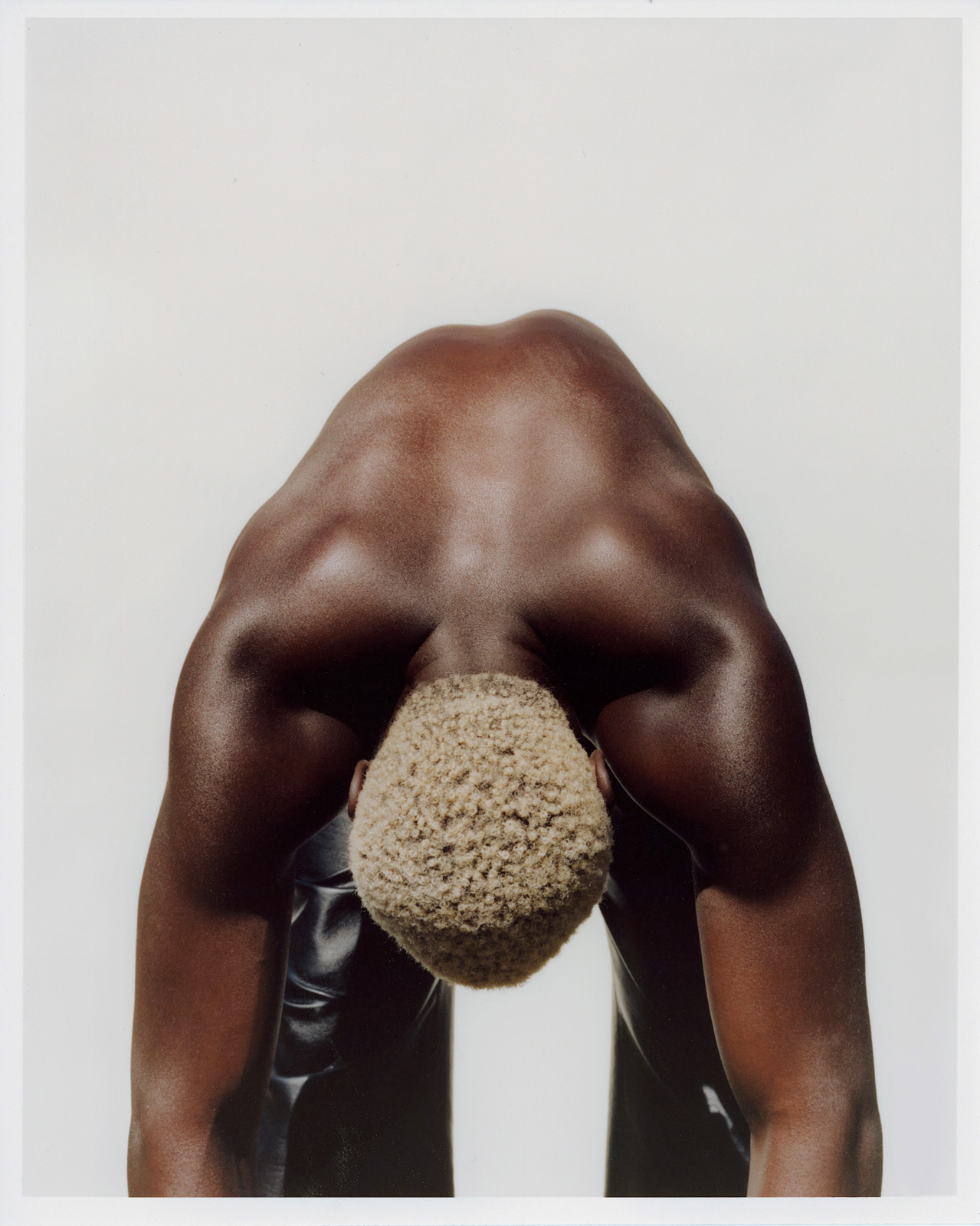

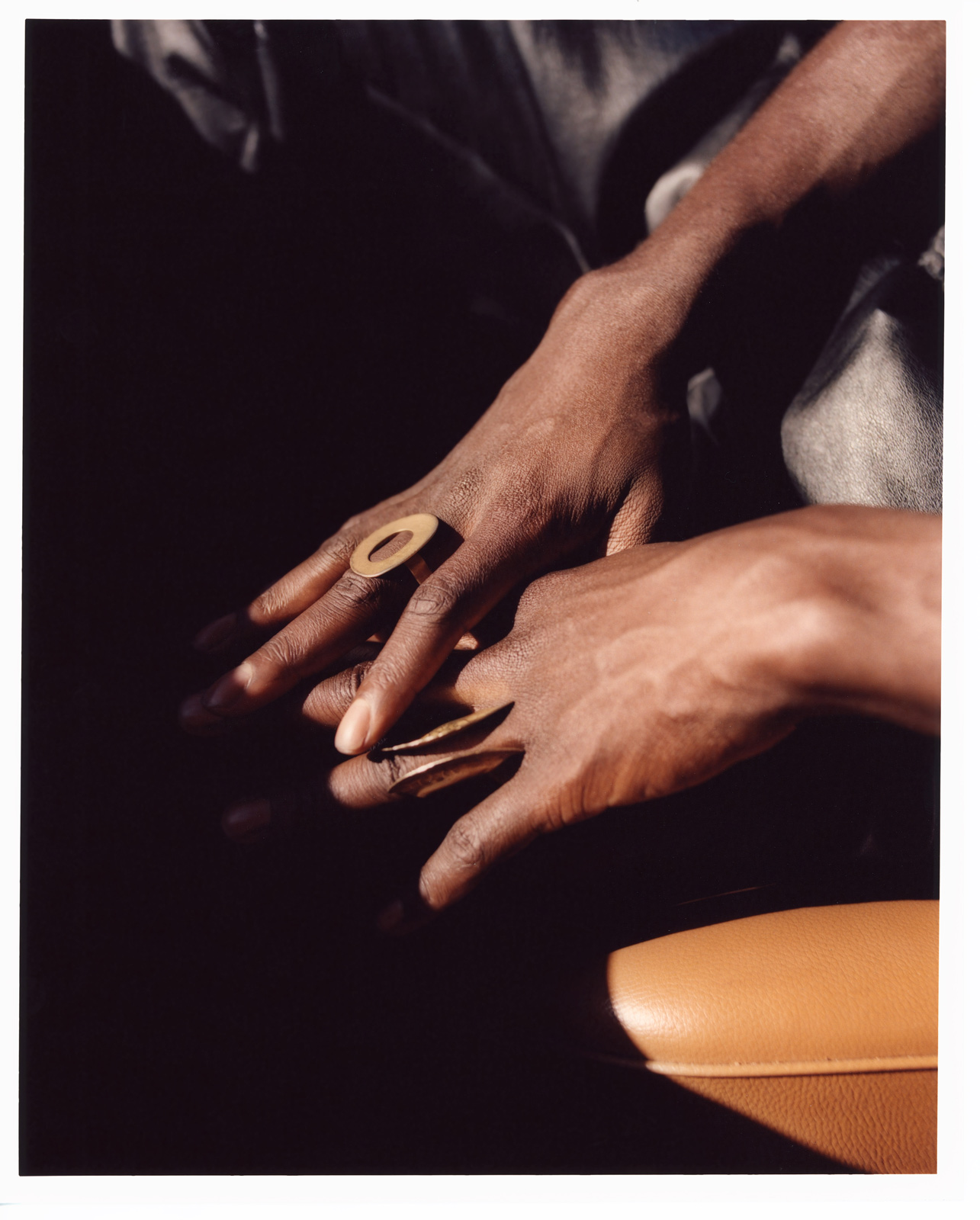

Sumney combines these disciplines in his latest project Live from Blackalachia, a live performance set in the Blue Ridge Mountains that challenges conceptions of the region and celebrates his relationship with the earth the work is filmed upon. The result, which is currently on view at Nicola Vassell Gallery alongside a selection of photographs is a dazzling execution of storytelling via choreography, wardrobe, and acoustics—one that belies the circumstances of its production, which required such Herculean feats as hauling a 40-foot technocrane up a mountain.

Holding a commitment to the multiplicity of his identity—which evokes Oscar Wilde’s eminent quote from The Picture of Dorian Gray, “to define is to limit”—Sumney invites us to what at first seems to be a performance in, but might be more aptly called a collaboration with, the divinity of nature. During ‘In Bloom (in the woods),’ the gentle humming of crickets supports the sonics of plucky acoustic strings. Sumney’s vocals playfully oscillate in volume and trickle with melody. He tells the hills secrets—you get the feeling they’ve let him in on a few of their own mysteries in return.

“I’ve needed a space to articulate my own loneliness, not at the level of state, or nation, or race, or place,” Sumney says in one interlude. Fittingly with his biblical namesake, Sumney leads us into the wilderness—and atop a blue-green mountain humming with life, we witness the freedom nature brings once we realize it doesn’t purport to define us.

Elizabeth Stewart: The simultaneous playfulness and reverence toward nature in this performance is moving. What was it like communing with the mountains and surroundings during the day and into the night?

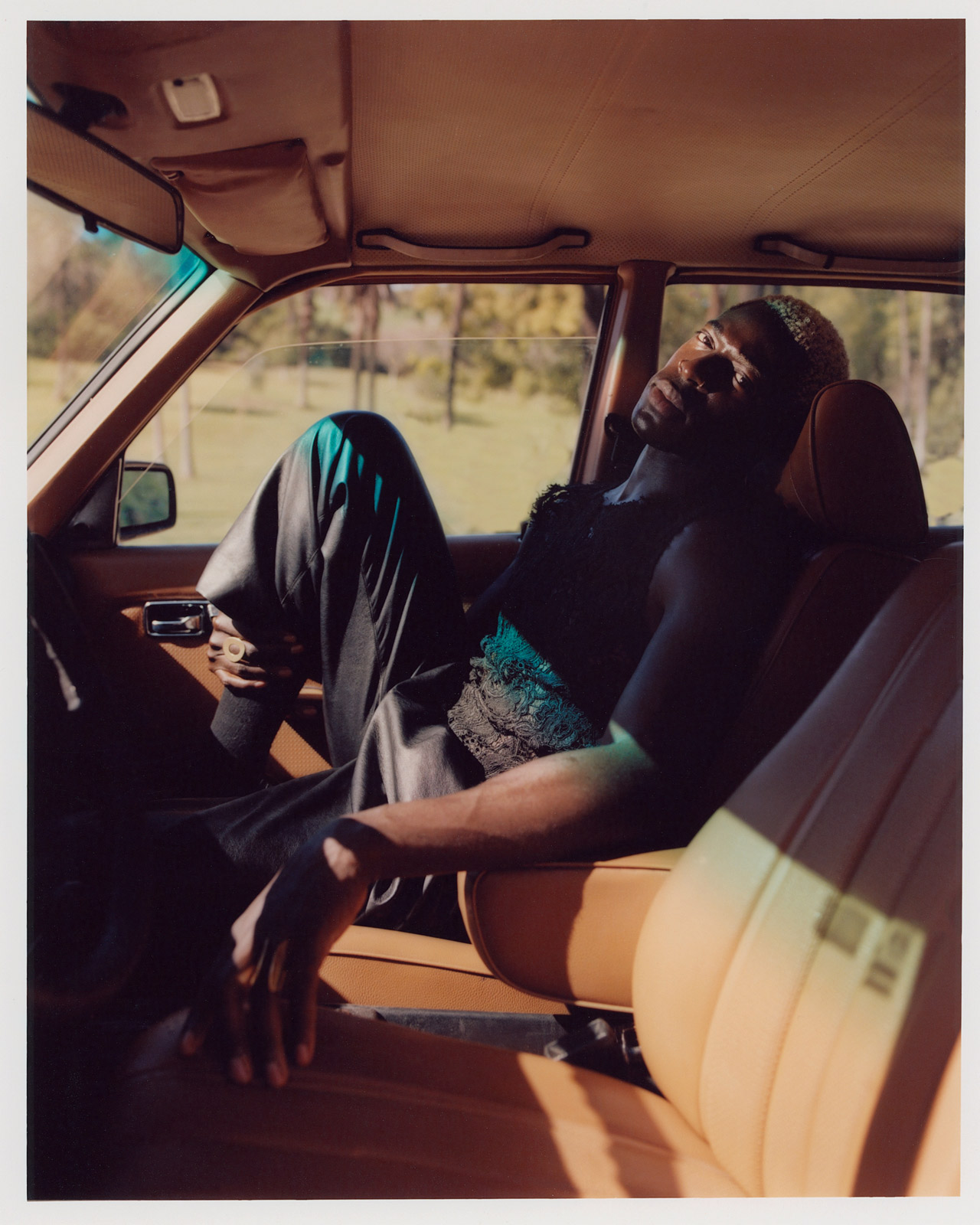

Moses Sumney: Shooting this film was a really spiritual experience. I moved here to be in nature, but I don’t actually go out to spend time in it as much as I’d like. I was in the process of making a film when everything locked down, and had to transition the entire concept; two things that made sense were to do something live, and to do something outside, where the air was blowing. So it was a perfect storm. I felt very honored that I could deal with the challenges and accept the rewards that nature has to offer.

Elizabeth: The term nature is so often gatekept and, at least in my mind, has different connotations. What does nature mean to you, as a word?

Moses: I think it is different for a lot of people—I never think of the beach, because I’m a mountain person. I think of trees and I think of forests and I think of rolling hills, but I also think of just going outside and being in the dirt, being in the grass. I did not grow up in nature, so I also think of nature as a return home. It has this beckoning quality.

Elizabeth: Can you tell me about your relationship to the Blue Ridge Mountains? I’m curious what drew you to this particular place.

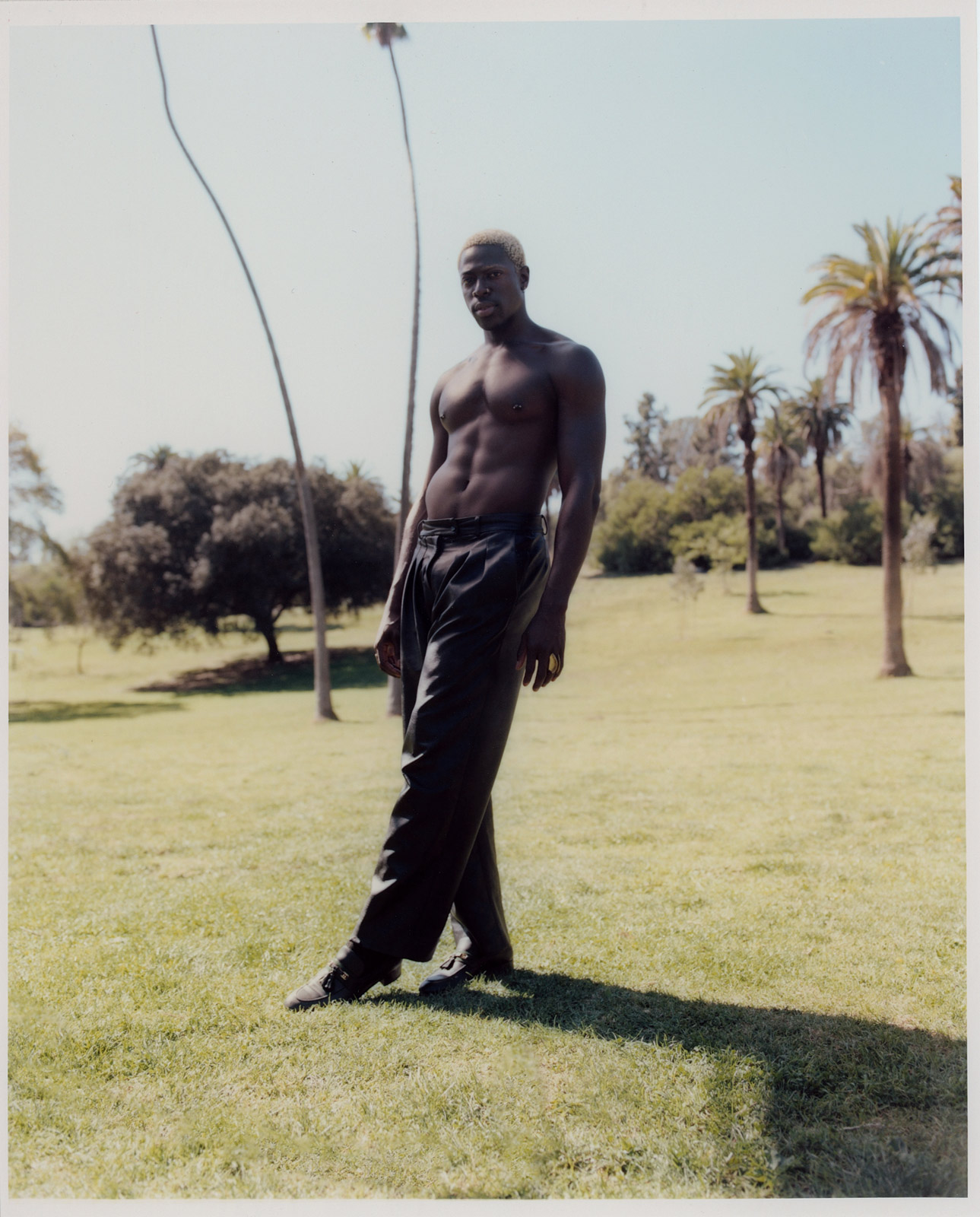

Moses: I first came here when I was on tour, opening for Local Natives many, many years ago, before my first album came out. Being in Asheville never felt like being in the South, in the way some of the other cute Southern cities did. With a 360-degree view of the mountains from the parking lot of the hotel, I immediately felt like I was in nature.

I met a friend for dinner who was playing drums in Dr. Dog at the time, Eric Slick. I was looking for a place to start writing my first album. He said, ‘Well, I’ll be going on tour, so why don’t you come back and live in my place for a month?’ So I lived in his house in Woodfin, which is north of Asheville. There was no phone service, no internet, and no friends—just solitude. That will always stand as one of the most life-changing experiences I’ve ever had.

I was born at the base of the San Bernardino Mountains, so I spent a lot of time there while working on my record. Southern California is essentially a desert, and [staying in] Topanga was just too expensive. So over the next few years, I would come back to Asheville every year to do some writing and thinking. One day, I was just like, ‘Why wouldn’t I just live in the place that I go to for inspiration? Why would I keep that as a small part of my life? That should be my life.’ And then I moved here.

There is a mystical quality to the Blue Ridge Mountains, as many people say. I think that there’s something in the ground that calls you to them, or calls you back to them. I found it really transformative being here.

Elizabeth: In your interview with Doreen St. Félix, you said, ‘There is a history of Black music being the foundation of bluegrass and country. There is a history of migration into and out of Appalachia. I’m so deeply invested in a reintegration into nature.’ Can you tell me more about your process in this research, and how you’ve woven it into your creative endeavors—specifically the making of Live from Blackalachia?

Moses: It’s important to note that I’m still in the process of learning the history of Appalachia and Black folk in Appalachia. The most emblematic symbol of Black people in Appalachia—and also the way in which African-Americans are integrated into Appalachia—is the banjo, right? [A version of the banjo] came over from Africa during slavery, and then during and afterwards it became known as an instrument native to this region. That’s an example of not only African presence and impact in Appalachia, but also the literal integration of white and Black Appalachians.

But I think also, over time, it’s become a place where fewer and fewer people of color feel safe and welcome. On top of that, there’s the narrative that it’s a place for white people, which isn’t necessarily true. But I think the narrative alone goes really far in keeping people out.

At the same time, Black people are still the largest minority in Appalachia. We hear a lot about Black Americans in urban settings, but there are a good amount of them in country and rural settings. So that’s really interesting to me, as a person who is very clearly not from Appalachia. I didn’t really grow up in the country, but I’ve been called to it for some reason.

Elizabeth: That is one of the many reasons I was curious to hear your perspective. You’re impressively manifold. You write poetry, you compose songs, you perform music, you take images, you model in the fashion world, you dance, you direct videos. How do you stay organized and centered?

Moses: Well, I definitely don’t stay organized! [Laughs]

I’m ruled by two things: deadlines and muses. And sometimes, the muse overrules the deadline, which becomes a problem for other people, but not for me. If something is due, but I’m like, ‘It’s so beautiful outside, I must go photograph it,’ that becomes the most important thing that day. And I guess that is the nature of being an artist. I’m willing to sacrifice organization and give in to chaos if it means that inspiration can reign supreme.

Elizabeth: As of late, who are your main muses?

Moses: There’s actually a guy who works at the local camera store. I started taking photographs during quarantine in 2020, and would go there every day to get film developed. He would by proxy teach me, and then at some point I was like, ‘I need someone to photograph, can I photograph you?’

I don’t know what it is about him, but he is so stunning and interesting, particularly in photographs. It’s funny if you see what he looks like, because he’s truly the nerd from the camera store, with big glasses and long, unkempt hair. So oddly, he’s been some kind of muse, but I’ve never really had muses that are people before. I feel very much like I’m listening to the sky for ideas, or moodboarding and watching films.

Elizabeth: I love your current muse. I’ve thought long and hard about this, and have decided camera store men are one of my favorite breeds of humans. Maybe that can be your next show at Nicola Vassell Gallery?

Moses: That’s crazy, because I do have about 300 photos of this person and I think they’re amazing. It’s just this random white guy, and I’m like, ‘This would be really weird as a show.’ [Laughs] It’s, I think, some of my best photographic work.

“I don’t have a prepared public identity or a mask that I put on so readily, but I must say I don’t need to, because it gets put on me anyway, for better or worse.”

Elizabeth: Correct me if I’m wrong, but this film felt very triumphant to me—as if you’re having this glorious return and reclaiming this space, in spite of and in resistance to some of the current cultures on this land. Is this something you considered and intended to express in the production of the film?

Moses: Yes and no. I am responding largely to perception of the space when I imply that I’m doing anything that’s defiant, more than I am responding to the actual land. Because I don’t find where I live to be hostile at all, and I don’t operate with a sense of fear. The defiance is, ‘What are you doing living there? What? You moved from LA?’ And I’m like, ‘Oh, no, I actually have to show how beautiful this place is.’ And people say, ‘There are no Black people there.’ And it’s like, ‘Well, I’m here. And I’m a Black person, and I’m making work, so that’s not true.’ [Laughs] So I think that’s where the defiance comes from, but I haven’t received a ton of pushback locally.

The triumph for me is also in embracing nature. It’s the easiest thing to do [spiritually], but in terms of production it’s actually quite difficult. We filmed a live concert outside on the top of a mountain over two days. Even if we had done that in the studio, it would have been incredibly difficult. We were dealing with the elements of weather and sound, and birds and bees, and bringing a 40-foot technocrane up a mountain. So there was a lot to overcome. I think also the triumph for me is in returning to nature at all, because I did not grow up in it. It’s even interesting I say return to it, because I’m speaking to something that predates my actual life when I say that. But yeah, that felt kind of good to say: ‘I am here and I am combining all of my disciplines here.’

Elizabeth: That came through in the work. Looking forward, what sorts of themes and ideas are you drawn to?

Moses: Interesting. [Laughs]

I’m laughing because I’m deciding if I’m actually going to tell you. I’m interested in intimacy, as well as talking about and exploring sex.

Elizabeth: As a poet, colors seem to be important in your work. What inspired you to make the shift into blue in the film?

Moses: We really lean into the lushness of the Blue Ridge in most of the film, and then for one song, ‘Colouour,’ we have our sunset look. ‘Plastic’ has hints of red as the sun is setting, as well. But then, I wanted to experiment with pushing it. I wanted to see what blue is too blue—to take it deeper, deeper, deeper, almost to the point that it’s flat, and then we pass a point to where it’s super rich.

I think that there is an actual hesitancy amongst darker-skinned people to embrace cold hues in photography. I wanted to say, ‘Okay, what does it look like to embrace the cold, and actually find the emotional warmth in the visual cold?’ And so that was a big part of going blue towards the end of Blackalachia.

Elizabeth: Returning to the subject of intimacy, you’ve had a moment as of late. You’re on the iconic Calvin Klein Houston Street billboard; you had this lovely gallery opening and, of course, the debut of this live album. How do you navigate exposure and intimacy as someone who’s in the spotlight? Do you find yourself utilizing an avatar in the public’s gaze in order to remain in character and equilibrium?

Moses: No one has ever asked me that in an interview. It’s a bold question, which I appreciate. I think we all have an avatar, which is to say that I don’t feel like I get to choose. I am who I am and I present how I present, and I think it’s honest.

However, your avatar is only 50% created by you. Regardless of how I present, people have an idea of me in public space, and it’s up to me to either be cool with it or agree with it or challenge it. Depending on who it is and how worth it it is, I might do any three of those things or none of them. And so I guess what I’m saying is, I don’t have a prepared public identity or a mask that I put on so readily, but I must say I don’t need to, because it gets put on me anyway, for better or worse.

And then the intimacy thing—it’s always been a problem for me, even before I started my career. I’ve always been a social outlier, coming up as an African in California and an American in Ghana, being the only Black student in the school. I was always—even when I wasn’t popular—known. Because of that, I’ve also never known how to fully engage in intimacy, and certainly I’ve never done that in a normal way. I think what has happened largely is that most of the people that I have been intimate with are also in the public eye, which I wouldn’t recommend. [Laughs]

Elizabeth: Really?

Moses: Yeah, because it really fucks up your brain to be in the public eye, and most of them have been more in it than I am. I can go out to New York and LA and play the game, and then come back to my house in the forest. So I don’t really think of myself as famous or anything like that. But I’ve also seen what it’s like for people who do, and it’s instant ruin.

Elizabeth: The WePresent website states, ‘Blackalachia is a performance piece about performance.’ Can you expand on this?

Moses: Those words are the writer’s choice, but I don’t disagree. I think because I’m both the director and the subject, it is quite meta. I’m making the choices on who the camera’s on and I’m also the performer.

But I’m also trying to communicate something about our live show. A lot of live concerts will mix and re-document footage, right? The most recent amazing one was Homecoming, which is a fantastic performance, but also you get the little rehearsal moments. I would never make something like that, because I don’t like people to know shit about me. [Laughs]

So we’re going to give you the live show, which is inherently documentary, but then we’re going to give you a dance sequence in the middle of a song, that in real time doesn’t make sense. We’re gonna give you me flying in the air during the most intimate song, and give you an extreme wide when it’s emotionally right here. We’re gonna give unrealistic blue light, and swim in the grass after our horn section gives the biggest thing. So I think a lot of it, for me, is a performance piece, and then it’s an art film, and it’s not just… ‘And here’s one, two, three, four!’ [Plays air drums] You know?

Elizabeth: Yeah, and the piece is full of many splendid surprises. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Moses: No! Watch the film. [Laughs]

Moses Sumney: Live from Blackalachia is on view at Nicola Vassell Gallery through March 5.