The multi-instrumentalist discusses his ‘Birdsongs’ EP series, charting his evolution from Brockhampton collaborator to indie upstart

Malibu, fall of 2020, hidden in the hills above Zuma Beach: Baird, a 23-year-old multi-instrumentalist and producer sits in Shangri-La, Rick Rubin’s studio. He’s there on invite with tempered expectations, imagining he’ll just go in and chop up some instrumentals for a friend. He dabbles in some psychedelics. As he arrives, the shrooms settle and his senses elevate. He closes his eyes and plays the guitar. Soon there’s an unexpected voice in his ear—one he’s heard, but only on wax. He can’t see anyone, but he knows who it is. It’s Kevin Abstract of Brockhampton, telling him to keep going.

Baltimore, late ’90s: A rising sun and “Living For The City” by Stevie Wonder fade up and fill the Acheson family home, waking a young Baird and his brother Gabe, and setting the tone for another weekend revolving around music. Soon their parents’ band would be over for a weekly living room jam—a sight the brothers take in before heading down to the basement to imitate, using a guitar, piano, and a coffee table as a makeshift drum set sans hi-hat. Finally getting a synth changed the game. “It was a really big deal when we got a mini Korg, which is a shitty little synthesizer,” Baird says. “We were like, ‘Now we can sound like Black Moth Super Rainbow.’”

Echo Park, LA, a few days after Shangri-La: Baird’s phone lights up. It’s a text from Kevin telling him he liked his sound in the studio and wants him to come out to upcoming Brockhampton recording sessions for their album, Roadrunner: New Light, New Machine. It’s a crew notorious for keeping its collaborative circle tight, so the invite feels like Baird’s first big break as a producer. He dives straight in, leading to credits on nearly every track and a feature on “OLD NEWS.”

“There were nights where it was just me, Kevin, Romil, and Joba staying up until 7 a.m. trying to finish a song,” he recalls. “Then everyone would pass out and Kevin would be up going through kick drum sounds all night. I was totally inspired—at the time, I was not a big writer, but they were just prolific. They’d start a beat, leave it on loop, go get a bite, ‘Oh, Dom’s ready to track, let’s go.’ Learning to flow just really helped me.”

Back in Baltimore, early 2000s: “Either you help me with the dishes or you practice piano,” Baird’s mother would say. “I’d usually choose piano,” Baird remembers. “But, you know, sometimes as a kid, when you’re asked to do something, it becomes a chore. I’d be like ‘I don’t want to be learning this classical stuff.’ It was tough at the time, but I’m glad I did it.”

Baird got his start just shadowing his brother’s piano lessons at age three. Soon it was his turn to play, and when both showed promise, the family took note.

“My dad always joked that, for a while, the piano was the most valuable thing in the house—more valuable than the car, the TV,” Baird remembers fondly. “Then I hit the teenage years—that sort of angsty period of life. I thought, ‘My brother is just always going to be better than me, I need my own lane.’ My dad always played guitar, so I was like, ‘Okay, I could too.’ I started picking up his guitar and then my folks put me in classical lessons for that, too.”

Although guitar became his primary instrument, he says his ear immediately goes to drums and lyrics when he hears something new. That orientation is apparent in his sound. Break neck drum grooves shuffle over varied percussion, forming a foundation for electronic and acoustic mosaics that he turns into mini narratives, with lyrics that feel like short vignettes about the changing experiences and relationships of a twentysomething.

November 2021, Los Angeles: Stevie Wonder’s in the air again, this time coming through Baird’s headphones as he glides on his electric bike through Mid-City, on his way to El Rey Theatre. He slows down as he approaches the venue. “There’s a line forming around the corner already?” he thinks. Role Model fans showing out. He parks, turns his bike and Stevie off, rolls in, and opens the show. With two full EPs out, and some traction from the Brockhampton release, a few fans know his songs.

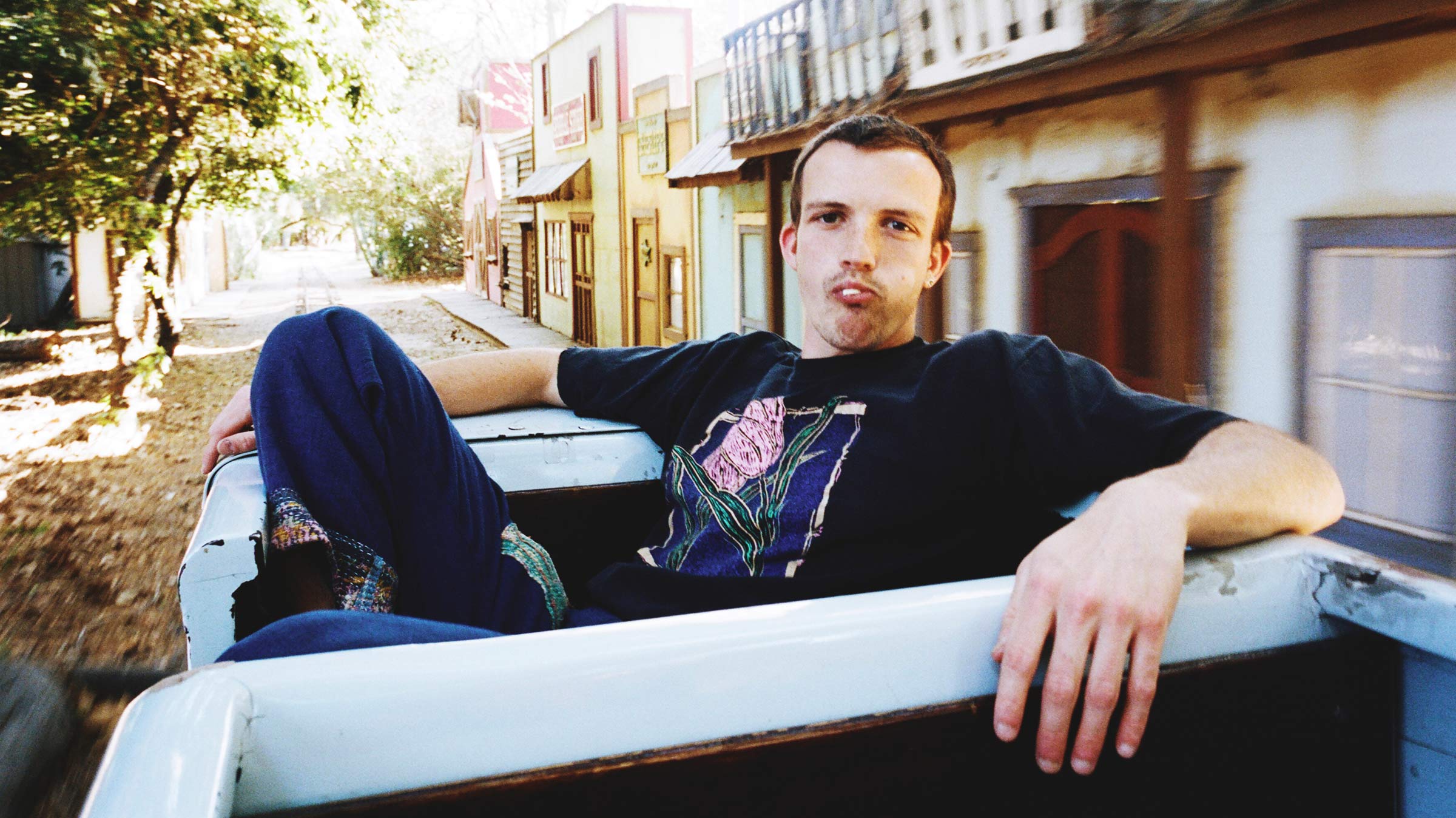

A few weeks later, we meet over jicama salads from Chichen Itza, a Mexican eatery in South Central LA, around the corner from a studio space Baird shares with Gabe. He walks and talks with slow confidence—baggy pants hang over Chuck Taylor’s, hazel eyes contrast with dyed dirty blonde hair. We dap and go back and forth and exchange what we’ve been listening to lately. He brings up an eclectic mix including Octo Octa, Robert Lester Folsom, and Dirty Projectors, and talks with a cosmopolitan drawl—a blend of Baltimore smooth and intonations tuned from living in Mexico City and LA since.

He just released his first single for BIRDSONGS, Vol. 3, a quick vibrant track called “Easy on Them Turns” that drew attention from KCRW and COLORS Studios, and was later paired with a video co-directed by Baird and Jack Bergert. Despite the success, he downplays his aspirations with blunt reality checks, wondering what the role of the artist will be on a planet facing irreparable climate collapse.

When he started his studies at Brown University, he was just trying to fit in. He initially kept his passion for music a secret, not wanting to be that one kid down the hall who’s trying to blow up on SoundCloud. But he was steadily making, and soon releasing, electronic music as flybear—a pseudonym paying homage to the Flying Lotus, post-Cosmogramma, Panda Bear universe so heavily influencing his sound. His stuff gained enough traction for him to land a deal with Big Beat, a sub-label of Atlantic Records. But he didn’t linger in that lane for long. Staying in the box kept him from his roots. Polished, classical instrumental training defined his youth—those jams in the basement were backed by serious time spent with theory and performance. His father, a high school history teacher, brought the educational mentality into the home. Hobbies had to be grounded in theory, in detail.

“It was definitely this sort of family band vibe,” Baird says. “There was even a little recording studio in our neighborhood that my dad booked for us once. We recorded four original songs before we really were recording stuff at home.”

School facilitated creativity, too. The spot his father taught at was a K-12 liberal arts private school where students call teachers by their first names—and some, like Baird’s dad, got onstage with the student band for performances. Baird and Gabe got free tuition because of the parent-student connection.

“I think you’re better off improving your instincts than trying to perfect something as if it was your instincts, you know?”

After graduating from Brown, he moved to Mexico City where he tapped into the frequency of the culture by reading books like The Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolaño, and studying guitarists before him like Rodrigo González. But he picked up the most by meeting locals. He befriended a philosophy student who was also a classically trained guitarist and they started playing together. Later, he was caught by a street performer playing classic bolero lines in a local park.

“This older gentleman was just ripping, and after he finished playing, I was like, ‘Yo, can I take lessons from you?’” The man obliged, and each week Baird would return for instruction. It was in this headspace that he’d finish BIRDSONGS, Vol. 1, and start on Vol. 2, before the pandemic forced him out of the country. He eventually landed in LA and moved in with his brother in Echo Park.

When we connect for a final chat in early March, we’re a few weeks away from the release of Vol. 3, but Baird starts off the conversation talking about the music he and Gabe have been making together. Gabe releases his own stuff as Goldwash, and the two have shared studio space for months, but they’re only recently tapping into the creative relationship they had growing up.

“On a creative level, that’s the most exciting thing to me right now,” Baird says. “I think it’s taken a while for us to get to a point where we’re actually functional collaborators, but I like working with him because neither of us pulls any punches. We don’t beat around the bush.”

Otherwise, he’s upgraded from the electric bike to a car, which he recently took out for a drive with Abstract to listen to BIRDSONGS, Vol. 3 in full. Since linking at Shangri-La, the two have become close friends, regularly exchanging new music and ideas. “He’s open to everything and usually has a take that I don’t fully expect,” Baird says. “He has the perspective of someone who’s been in it longer and knows what’s exciting and what’s played out.”

Vol. 3 is a realization of the sound Baird’s been honing since watching his parents perform in the living room.

“I’m just letting things flow,” he says of his creative process of late. “I think you’re better off improving your instincts than trying to perfect something as if it was your instincts, you know?”

“Things are going better than I would have thought two years ago when I moved here from Mexico City, not really having a plan beyond the next month,” he continues. “I was hoping to make three mixtapes and see if I could make a career out of it. And so far I am. Now, I want to push it. You can do a lot more than you think if you really cut loose.”