'And They Earned Eternity in a Brief Space of Time' explores public memory and the city's downtown architecture

Alix Vernet’s first solo exhibition, And They Earned Eternity in a Brief Space of Time, at Helena Anrather Gallery, pays thoughtful attention to overlooked corners of New York City, particularly in the East Village and Lower East Side.

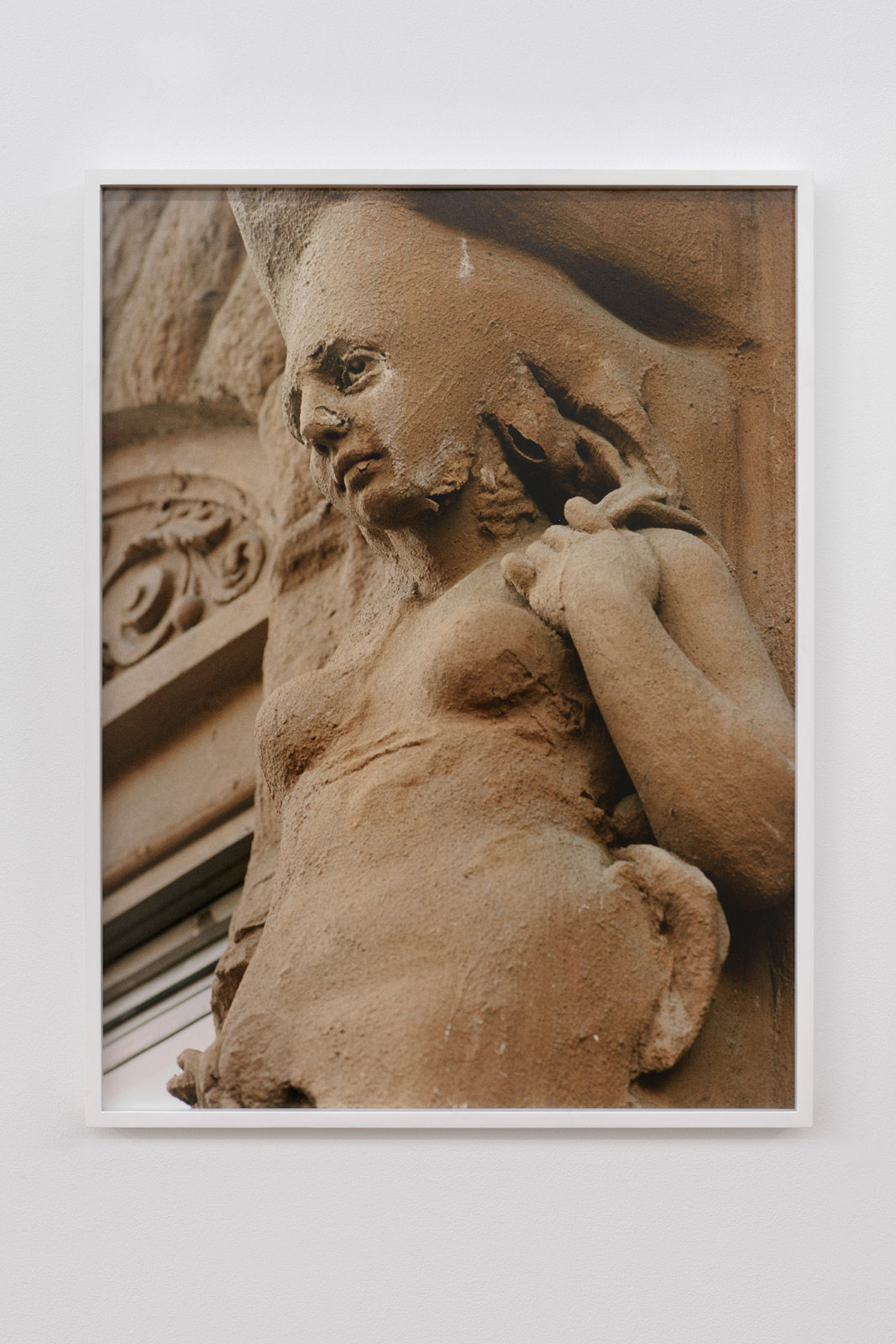

Driven by a fascination with the adorned buildings of New York’s downtown, Vernet—with the support of accommodating tenants—climbed through windows and up fire escapes in an exploration of the communicative capacity of urban surfaces. The result, a series of casted letter forms, large scale photographic prints, and what the artist calls “veils,” work together to evoke a mesmeric, celestial tone, asking the viewer to gaze a little longer.

Syd Walker: Hey, Alix. I’ve been a longtime fan of your work and am elated that we have connected. Congratulations on your first solo exhibition! What has your trajectory toward your current work looked like?

Alix Vernet: When I first moved to New York, I had a difficult time figuring out how to make work. Finding a studio was kind of a nightmare, and I felt that the city organically eclipsed any attempt at sculpture. I had tried wheatpasting when I was 18; it ended quite badly, so I became very paranoid about trying to do anything in public. Before Covid, I was making works from dollhouses. It was something I could fit in my apartment. Eventually I was just like, ‘Why am I trying to make things that rely on separating myself from where I am? I should just make molds of the city, of what’s around me.’

Syd: Your work seems to be centered around the idea of preservation and paying attention to corners that may otherwise be overlooked. Was this idea the catalyst to start your practice, or was it eventually found through your process?

Alix: In the fall of 2020, I started shadowing a monument technician—Theo Boggs, from NYC Parks. At the time, I wanted a better understanding of the way public memory informs the design of public space. A lot of what the Department of Parks does tends to involve more preventative work, rather than ‘restoration.’ The first time I met Theo, I showed up to Washington Square Park while he was power washing the arch on a cherry picker. I honestly had no expectations—I just watched the way passersby interacted with the process, and was sweeping up all this marble dust.

Towards the end of the day, he was like, ‘Hey, do you wanna come up?’ I had brought the tiniest bit of clay and made an impression of one of the stars at the top of the arch. From there, we started semi-covertly collaborating. I would sneak out of work to follow him around on different jobs; this is where I developed a lot of the methods of working outside I use now. Ultimately, I really don’t think my work serves the same function, but it was interesting to see how these paradoxes of care play out on a public scale. Like, the power washing involved in most graffiti removals can be more aggressive to the surface of the stone than graffiti. The pursuit of timelessness can be more damaging than the passage of time itself.

Syd: Can you tell me more about your choice of materials? Particularly the use of cheesecloth and latex in pieces Lady, Saint Marks, and Veil, 1B, East Broadway.

Alix: I was thinking a lot about the nature of surfaces in this show—specifically urban surfaces and how they function as shared records. I like this quote: ‘A surface is what insists on being looked at, rather than what we must train ourselves to see through.’ There’s something quite girlish about it.

The clay works, I first tried mid-Covid. I was trying to figure out how I could arrive at sculpture through the city. I had experimented with rubbings, but clay held more possibility for me in reflecting my own hand. The first time I tried it, I literally just hit some clay against the surface of a building next door to me. I was nervous about more involved processes like silicone, and wanted something that was fast—where I could do it, and get out quickly. The latex works, I tried once I got a bit more confident in working outside. Cheesecloth is a pretty standard reinforcement tool used in mold making, but I think it helps form a thread between text and textile.

The technique I used in the show at Helena Anrather was something Heidi Bucher developed in the ’70s. A similar peeling process is also used in art preservation to remove grime from surfaces. One thing I was thinking about a lot with this show, was putting these practices associated with a sort of domestic feminism precedent in conversation with public maintenance, architectural theory, street action, Dada.

Syd: Going off of that, why did you choose a silvery coating for all of the works at your most recent show?

Alix: The silver I came to somewhat intuitively. It’s a color you see a lot in the city, whether it’s spray paint, the albedo roofs, or as a quick-fix cover-up. Some have interpreted the color as tying the work to photography—some as armor. I like that it can be used to both attract or deflect attention.

Syd: What does your process or research look like in finding what buildings you’d like to work with?

Alix: Most of the surfaces were products of chance or places I came across on my way to work. For me, research happens through process. I try to make myself susceptible to affect before chaperoning my experience from a governing source of meaning. I got kind of obsessed with how hyper-decorative many of the buildings downtown were, and how most of the surfaces were almost identical or reciprocal versions of each other, like the ladies on St. Marks and their twins on Henry Street. I informally cataloged the sites in my phone notes, and went back to photograph them.

The conflation of femininity and deceit is something I thought about a lot while in college, especially as it relates to architecture. After my first larger scale mold, I started reading more about the history of specific buildings. Most of those, I noticed, were built by Jewish immigrants during the early 20th century. It was this interesting time, where industry had made materials typically considered a luxury more readily available, and builders were able to make these more elaborate, adorned structures. There was all this beef, because the upper-class landlords were threatened by seeing their own codes of prestige used against them, and started a whole smear campaign against the decorated tenements as ‘skin built’ artifice.

Syd: I would assume creating a body of work like this requires a lot of time. What do you do to keep the fire of interest, excitement, and commitment alive when working on a long-term period project?

Alix: It was definitely a product of endurance. I mean, I think the actual production of this took about six months, but I had been ideating some of these things for a while. Half the time, you’re learning how to do something as you’re doing it. It’s so easy to get sidetracked and waste money on dead ends. My girlfriend helped me so much, as did my friends. Helena and Megan really supported my experimentation, which was encouraging. Although I think I drove everyone kind of insane by the end of it. [Laughs]

Syd: I’ve seen on your Instagram that many of your video clips involve your physical body, movement, and interaction with the space or materials around you, like a site-specific performance piece. Can you talk a little bit about that side of you?

“With these past projects, I’ve been craning my neck upwards. But I’m looking at the floor a lot lately, we’ll see if that takes me anywhere.”

Alix: The label of ‘performance’ in this work is something I go back and forth on. Like, when I was working with Theo, he was very adamant that I shouldn’t say I was ‘posing’ as a technician, because artistic labor is real and doesn’t always need to be framed as a performance. In my daily life, though, and in my art, I do feel like I need to borrow the codes of respectability of other fields or spaces. In a way, recording the process of making something is a place for me to explore these dynamics.

Syd: Are tenants and landlords typically willing to let you work on their buildings? How have you navigated those conversations?

Alix: It depends. I had been eyeing the ladies on St. Marks for a year before I tried to make a mold. I have a somewhat nervous disposition; it actually wasn’t until the ladies on Henry Street disappeared that I gained some confidence. There was a point when I tried making these flyers and putting them on people’s buildings—that was a big fail, they got removed within the hour. The internet ended up being a big help. I posted asking if anyone knew someone in the building on St. Marks, and luckily, I connected with someone.

I knocked on the resident’s door in my little painter outfit and hoped they wouldn’t be weirded out, or call the landlord or something. I’ll usually show photos and explain my process. Even though I’m mainly on the fire escape, it’s still a lot to ask of someone to let a total stranger through their home, and have to coordinate when they’re available. I was honestly stunned by some of the neighbors’ generosity. I found it’s a great exercise for me to have to explain what I’m doing and involve other people’s opinions and perspectives. It’s a more dimensional process than sneaking around. One conversation involved a negotiation at the Wall Street Baths and a strategic Supreme jacket purchase. But I will leave it at that…

Syd: At your opening night, I sat back and observed many people spend a decent amount of time staring at, and trying to decode, Here Are Enshrined, Reliefs from Brooklyn Public Library, Central Branch—almost like a word search puzzle. Was this your intention, or something you foresaw as an opportunity to get viewers more involved with the piece?

Alix: I was thinking a lot about ‘surface reading,’ as well as the display of text fragments in museums and how these held a parallel to the look of avant-garde poems. There’s a certain absurdity to public inscriptions. They involve tackling these really big, nuanced ideas, but most end up relying on a kind of aspirational, evasive rhetoric, kind of the OG copywriting. Sometimes, they’re really weird and specific, though—like, quite good. I was thinking about what happens to a word, a letter, when it outlives its function, or doesn’t uphold it. There’s a kind of internal breakdown.

Part of the reason I included the photograph of the Manhattan Bridge plaque was because I loved the way all these men’s names, who had built this major site of transit, had turned into, like, an erotic plea. With Here Are Enshrined, I wanted to try and visualize the experience of walking past language to get to poetry. A kind of ‘meaning cemetery’ that can end up becoming a place of possibility and rearrangement.

Syd: Some of the phrases feel a bit ethereal. Are they inspired by something specific?

Alix: The piece I AM TURNING INTO AN ANGEL PLEASE LEAVE was actually something someone said to me while I was making impressions of the letters at the Brooklyn Public Library. In my last project, I was playing with redaction, isolating certain words from their whole. Most of the letters were products of what I could get in a short moment. In this body of work, I was able to spend all day at the site, since I had permission. So much happens when you just sit in place all day.

It was getting late, and I had been making impressions of these smaller letters across the entrance of the library. This woman came up to me and we talked for a bit. She suddenly exclaimed, ‘I am turning into an angel, can you leave?’ I was kind of just like, ‘I have to finish up here.’ She sort of guarded me until I finished, and then I left. Her words reminded me of the ladies on St. Marks somehow.

Syd: Lastly, I’d like to ask what’s next for you, though I don’t primarily mean it in terms of production—unless you are in process. What you recently put out is no small feat. Are you taking some time to re-energize from this last show? Do you have plans for the next?

Alix: I’m hoping to get a bit bored and have some time to try new things. With these past projects, I’ve been craning my neck upwards. But I’m looking at the floor a lot lately, we’ll see if that takes me anywhere.