Photographer Laurence Ellis captures creative community on the fringes for Document’s Winter 2021/Resort 2022 issue

When tourists come to Slab City, California, most get dropped off at Salvation Mountain, the outsider-art-monument to God’s love that onetime resident, the late Leonard Knight, erected over the course of 28 years. The dazzling man-made mountain, built from plastered-over refuse and covered with thousands of gallons of pastel paint, is emblazoned with giant aphorisms like “GOD IS LOVE” and “GOD NEVER FAILS.” Tourists are advised not to venture too far into the surrounding desert, so they take their photos and get back on the bus, which drives them in a loop so they can observe the community of off-the-grid squatters from a distance. Many go home without ever leaving the designated visitor areas, and even fewer stay after dark.

When British photographer Laurence Ellis rolled past the sign announcing “SLAB CITY: THE LAST FREE PLACE” in his rental car, it was already almost dusk. He could make out the silhouette of Salvation Mountain rising in the distance. Then, in a flash, a dog trotted out from behind the dry brush and—thud—disappeared under the wheel of a passing car. Shocked, Ellis slammed the breaks and ran over, but the dog had limped off into the twilight. The driver who hit the animal wasn’t fazed—there are many dogs roaming Slab City—but Ellis wanted to find the wounded creature, or at least its owner, so he spent his first night driving around in the pitch black asking strangers if they’d seen it. He never found the dog.

Slab City is an unincorporated city in the Sonoran Desert with no electricity, sewage lines, or running water. It is populated by a mostly transient community of social outcasts who can’t or won’t conform to the rules of “Babylon,” their term for the outside world. It was once home to Camp Dunlap, a Marine training base commissioned in 1942 and dismantled in the decade following World War II. The site was slowly repopulated, first by veterans who trained there, then by drifters and RV owners, and renamed after the cement slabs upon which they built their encampments. It boasts a handful of ragtag establishments, including an outdoor music venue and a soup kitchen that doubles as an unlicensed bar, slinging one-dollar cans of Bud.

Some Slabbers—as the residents call themselves—are fleeing debt or the long arm of the law; others were driven out of their homes by addiction or mental illness. Some landed here by accident and liked the vibe. The scavenger-survivor lifestyle, while it agrees with many of the people living it, reflects the dark, Mad Max undercurrent of the American dream. After all, what’s more American than an ex-military base occupied by people who the government abandoned, who have managed to eke out a life through sheer ingenuity and elbow grease?

Slab City is not only a refuge, but also a movement of people reimagining their relationship to the land. It’s one of the few places in the U.S. where anybody can show up and park indefinitely, and while it’s certainly no utopia, it offers an escape from rising cost-of-living expenses that grind people down. In that sense, it exists on a spectrum of outsider spaces, from illegal raves—unused land transformed into leisure space—to the seasonal worker caravans depicted in the film Nomadland, where people experience the hardships of itinerant life without Slab City’s libertarian glamour. This autonomy, however, is threatened by rumors that the state wants to sell Slab City. And even if residents were to buy the land, they’d have to start abiding by real-world rules like property taxes and building codes. Some say that if landlords were to enter the picture, it would destroy the Slab City dream: of a place where having a home is a right, not a privilege.

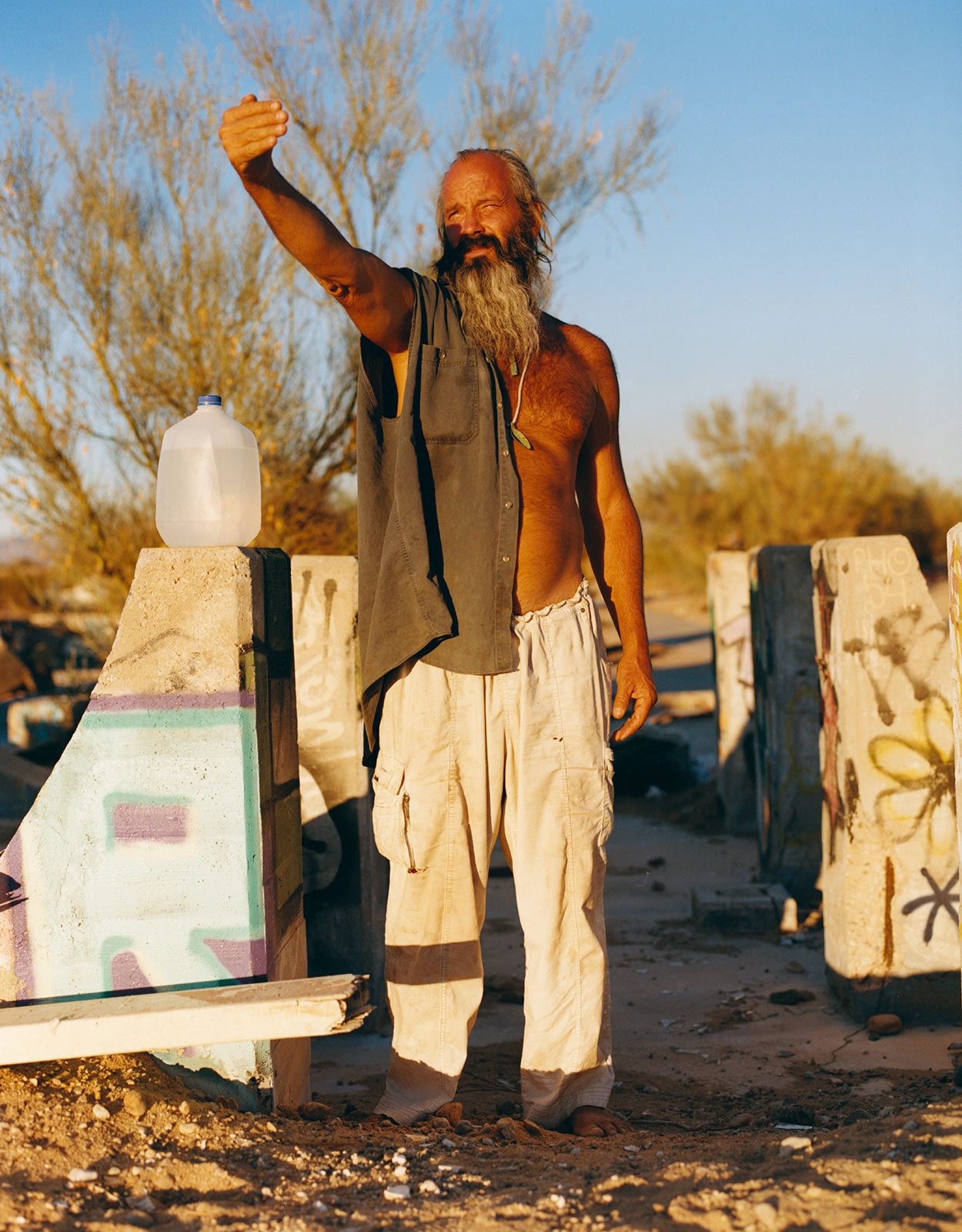

In one of the most striking portraits from Ellis’s visit, a man bathed in balmy, golden-hour light has his arm extended out in front of his face, with his hand bent into an L-shape, and he’s squinting. His name is Woody, Ellis says, and he was practicing a form of meditation called sungazing. “I wasn’t going to try it because I’m a photographer and it’s apparently very, very dangerous,” Ellis laughs. “But apparently, if you do it close to sunset, it’s not so bad.” Woody hadn’t seen his daughter in three or four years, so Ellis proposed making a photo for her. “What I say to my subjects,” he explains, “is if this isn’t benefiting you in some way, you shouldn’t do it. I don’t want to come here and take a photograph. I want to create an image with you, and at least it should be a nice experience, but I want it to be more collaborative than simply me finding you interesting.”

Slab City’s harsh conditions make it difficult to secure basic necessities. Clean drinking water, for instance, is only available for purchase one town over, dispensed at a vinyl-sided shack with old-timey signage in the colors of the American flag, advertising “QUALITY DRINKING WATER.” The groundwater in and around the Salton Sea, a shrinking saltwater lake adjacent to Slab City, is full of lithium mineral deposits that have attracted the interest of battery manufacturers like General Motors. Residents also extract lithium at a smaller scale and sell it to pay for potable water and electricity.

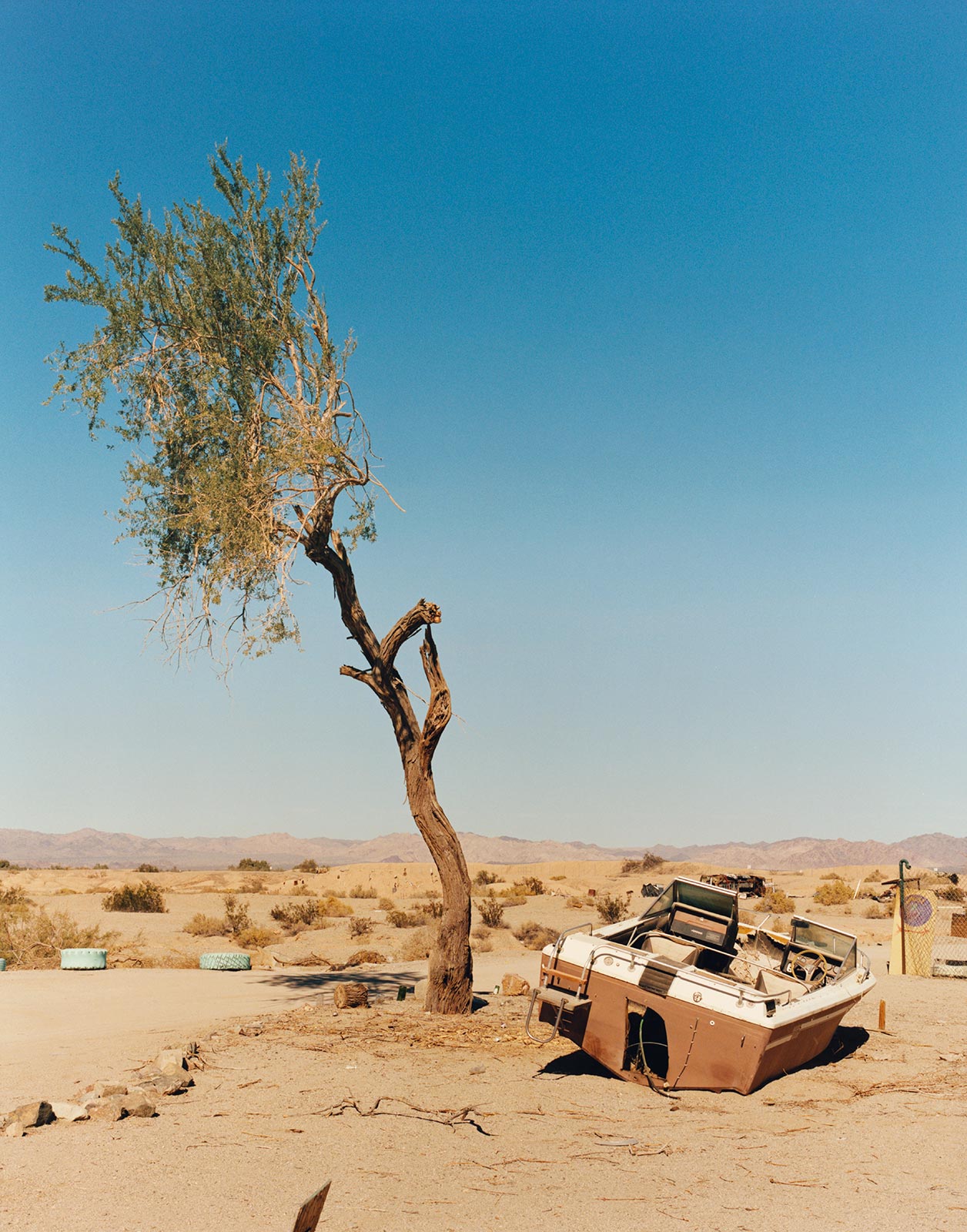

They’re equally resourceful when it comes to art, which is everywhere you look in Slab City. Down the road from Salvation Mountain, the folk art mecca of East Jesus is littered with steampunk-style installations made out of whatever the artists had at hand. In the sculpture garden, you’ll find a sundial made with slices of corrugated metal laid in a spiral, like fins sticking out of water; a “can organ,” which consists of rusted cans of different sizes that produce different frequencies when dripped upon; and a dealership’s worth of derelict vehicles transformed into flamboyant elegies to American car culture. Slab City is living proof that art doesn’t have to be a luxury commodity: It can be the thread that strengthens a community’s social fabric.

It would be naïve to paint too rosy a picture of Slab City, and disingenuous to harp on the hardship. The real story lies somewhere in the middle. This comes across loud and clear in one photo in particular, of a bonfire blazing at sunset in a circle of shabby couches and plastic chairs. The desert landscape appears as unforgiving as ever, and the furniture looks flea-bitten, but the sky is a soft rainbow gradient and the fire beckons you to take a seat.