As celebrity biopics reign supreme, how involved should their subjects be in shaping their own narratives?

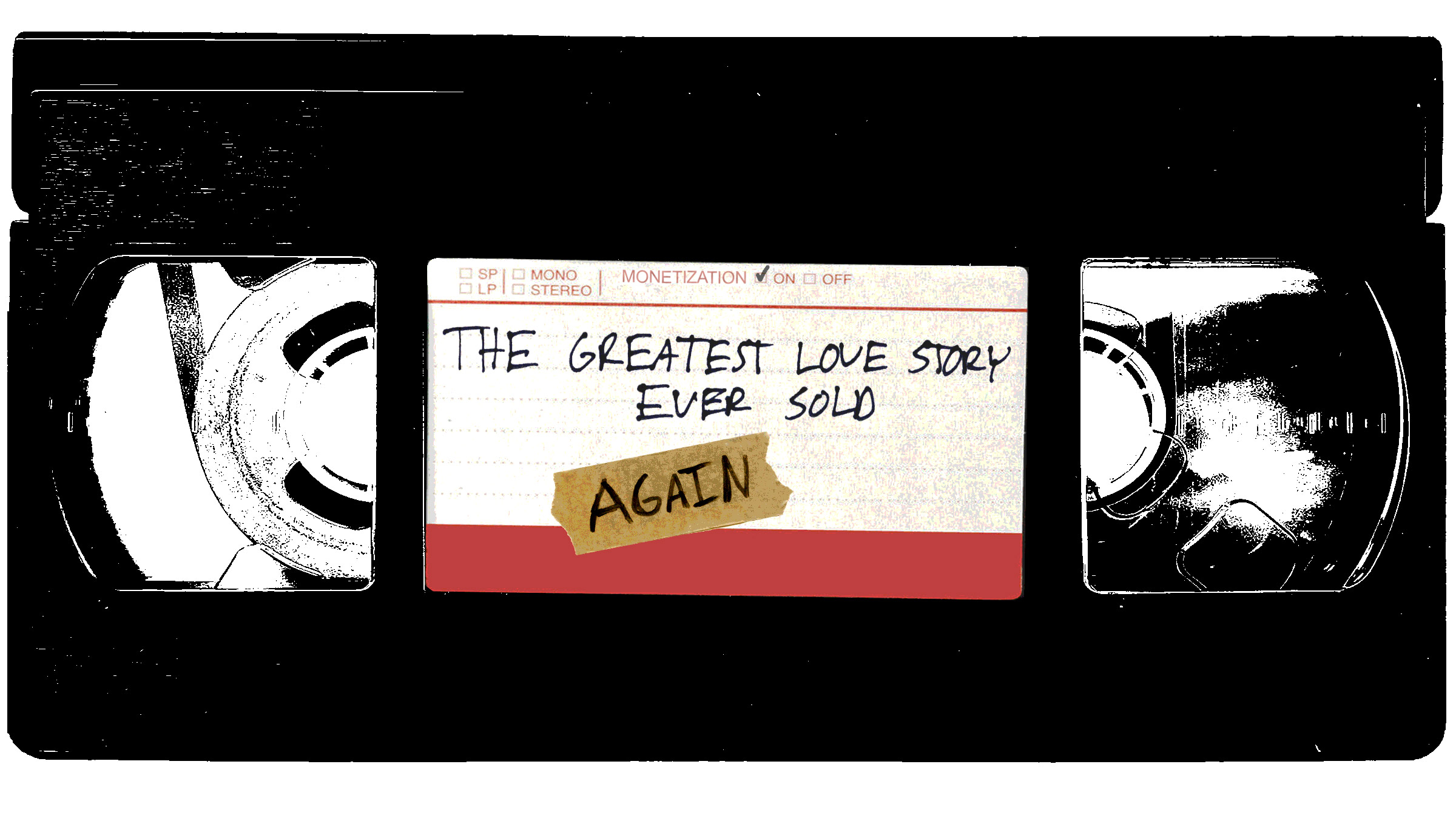

There is a grossly obvious irony to the making of Hulu’s Pam & Tommy. The eight-episode series has branded itself as “the greatest love story ever sold,” claiming a progressive, post-Me Too take on a tale that follows the violations of privacy and horrifying lack of consent around the release of a 1995 sex tape of Pamela Anderson and her then-husband Tommy Lee. The series, like the tape, was created without Anderson’s consent.

“The greatest love story ever sold” has been sold again. Only now, power players in Hollywood are exploiting the story of a woman being exploited. Though Lee is portrayed as the posterboy for hot-headed celebrity, the Mötley Crüe drummer’s inhumane behavior is mostly depicted as directed towards the man who stole his sex tape—Rand Gauthier. Perhaps this effort to complicate the narrative (which, as with most every story involving consent, is unnecessary) actually draws sympathy for Gauthier, a man who gave no such sympathy to Anderson when he decided to profit off of her suffering. Gauthier’s character is made to be even more sympathizable, with the casting of the ever-charming Seth Rogen. In actuality, Rogen’s character was not much of a victim, and Lee’s abuse of him was nowhere near what Anderson suffered at his hand. Lee was convicted as a domestic abuser after striking Anderson while she was holding their infant son.

“Celebrity biopics are almost guaranteed home runs. But they introduce ethical questions of ownership, regarding who gets to tell whose story.”

It seems unfair that Pam & Tommy is marketing itself with its so-called devotion to telling a story that is fair to Anderson, without her involvement or consent. “We particularly wanted to let Pamela Anderson know that this portrayal was very much a positive thing, and that we cared a great deal about her, and wanted her to know that the show loves her,” producer D.V. DeVincentis said in an interview. “We didn’t get a response, but considering what she’s been through, and the time that we were reaching out, that was understandable.” Lily James, who plays a rather convincing Anderson, has gushed about how desperate she was to do justice to her character in a slew of interviews. “It’s just one of those stories that you can’t believe hasn’t already been made into a movie or a TV show,” writer Rob Siegel said. “It’s kind of amazing that it was still out there, and it wasn’t snatched up that first day it came out. To me, it screams limited series.”

Siegel is right in that the appeal is undeniable. Celebrity biopics are almost guaranteed home runs. But they introduce ethical questions of ownership, regarding who gets to tell whose story. In a vaguely similar tale of infamy, Monica Lewinsky’s story was reframed in Ryan Murphy’s Impeachment: American Crime Story. But Murphy took Lewinsky on as a producer, allowing her a voice in the retelling of that narrative. Craig Gillespie’s I, Tonya lays its foundation on interviews with Harding herself. The foundational equivalent in Pam & Tommy may just be the sex tape, which is played again and again. If you hadn’t seen it before the series, you’ll feel like you have after watching it.

Now, obviously, some stories need to be told without the consent or heavy hand of all parties involved. But the ethical codes feel very different when retelling the story of a serial killer or a fraudulent biotechnology entrepreneur, compared to the story of a victim.