‘A New Bend’ at Hauser & Wirth includes textile-based artworks by Eric N. Mack, Sojourner Truth Parsons, and Dawn Williams Boyd

Nearly 20 years ago, The Quilts of Gee’s Bend went on display at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. The exhibition featured the work of 42 artists and spanned four generations, from the 1930s to the turn of the century. The artists in question were all women, who lived and practiced in Gee’s Bend, Alabama—a historically Black community first formed around a cotton plantation, and named after a slaveholder. Gee’s Bend rests on a peninsula—it was difficult to access any nearby Alabama towns until the late ’60, when the only road out was paved. “Isolation has always been the place’s curse,” wrote Michael Kimmelman in the New York Times, once the show had traveled to the Whitney. “But also, because it has protected the community and been a means of incubating art, a blessing.”

The Quilts of Gee’s Bend had a monumental impact on the modern art community, bringing global awareness to a creative collective that had previously known mostly local acclaim. Originally produced for functional purposes, the Gee’s Bend quilts were made of found material—old clothing and commercial packaging—and stitched into geometric, minimalist, strikingly colored designs. They became instruments of community building and political consciousness-raising; they garnered funds for the hamlet, and brought residents together through cooperatives like the Freedom Quilting Bee of the civil rights era, which provided Black women with an alternative economic model through which they could autonomously provide for their families.

“The Gee’s Bend [quilters] are, in so many ways, technologists presenting future imaginaries.”

Like isolation, fame has also proven to be Gee’s Bend’s simultaneous blessing and curse. Bill Arnet, the white collector who originally purchased dozens of the works, allegedly cheated some of the artists out of thousands of dollars in proceeds. Arnett and his sons were sued by two quilters, Loretta Pettway and Annie Mae Young, back in 2007. The case was resolved without comment from either party. “You’re making money,” once said Pettway of the Arnetts, while pointing to a glossy book filled with reproductions of her work. “Because you ain’t going to be doing this if you’re not getting paid.” Indeed, she had received payments from the Arnetts, “ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars.” But one of these quilts can sometimes sell for more than $20 thousand, and Bill owns the most valuable few. He’s said that he won’t sell them on the open market.

The New Bend, curated by Legacy Russell, is currently on view at Hauser & Wirth’s downtown gallery. The exhibition features the work of 12 contemporary artists—Anthony Akinbola, Eddie R. Aparicio, Dawn Williams Boyd, Diedrick Brackens, Tuesday Smillie, Tomashi Jackson, Genesis Jerez, Basil Kincaid, Eric N. Mack, Sojourner Truth Parsons, Qualeasha Wood, and Zadie Xa—whose creative practices engage in conversation with the Gee’s Bend quilting tradition. The show is an exemplary illustration of how to celebrate a body of work without exploiting its originators—without speaking on the founders’ behalf, or on behalf of the Gee’s Bend quilters still producing today. “[The exhibition’s artists’] unique visual vernacular exists in tender dialogue with, and in homage to, the contributions of the Gee’s Bend Alabama quilters,” reads the gallery’s press release.

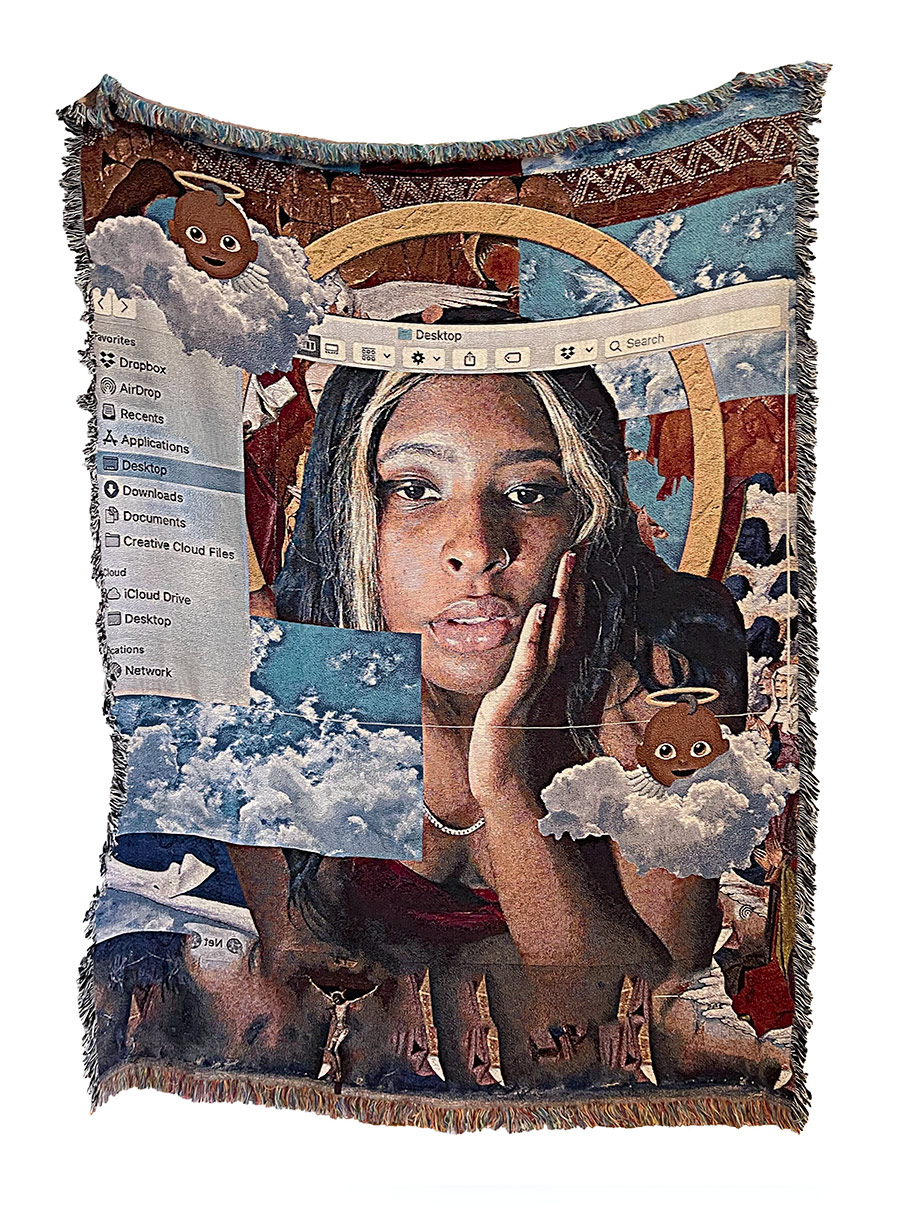

“This is an exhibition that has long been a dream of mine,” said Russell during a preview of The New Bend last week. “The Gee’s Bend [quilters] are, in so many ways, technologists presenting future imaginaries.” The works that the curator and writer selected are wide-ranging in both medium and perspective. There’s a tapestry by Qualeasha Wood, the show’s youngest artist, that strikes you as soon as walk through the door: a woven self-portrait in cyberspace, laid over a MacBook finder, decorated with swaths of cloudy skies and crucifixes and baby angel emojis. Jubilee, by Anthony Akinbola, is stitched from durags in pastel yellows and pinks; Tomashi Jackson’s Among Fruits layers acrylic paint, soil, paper potato bags, and archival prints on vinyl; Zadie Xa’s Ancestor Work series combines the tailoring of traditional Korean garments with quilting’s quintessential methods, to construct linen banners rich with cultural symbolism.

“This exhibition, in many ways, is reparative work,” said Russell. “It is a work about a group of artists, coming together in this moment, writing a love letter to the women of Gee’s Bend.” A New Bend is a modern contribution to a long-overlooked artistic tradition: one that’s been built by the Black women of the American South, within community and for community. It’s a spirit of art-making that’s rare to come by in the industry today, and a canon that, in Russell’s words, “reaches right forward to the present day.”

The New Bend is on view at Hauser & Wirth’s 22nd Street location until April 2nd. Learn more about Gee’s Bend’s quilters and support their mission here.