For Document’s Winter 2021/Resort 2022 issue, two generations of performance artists unite to discuss abandoning time, learning from one another, and the inspirations behind their death-defying craft

“Whatever you’re experiencing, you have to dedicate yourself to it completely,” says performance artist Miles Greenberg. “It needs to feel like it’s going to be the rest of your life, because that’s the only way that you can abandon time.”

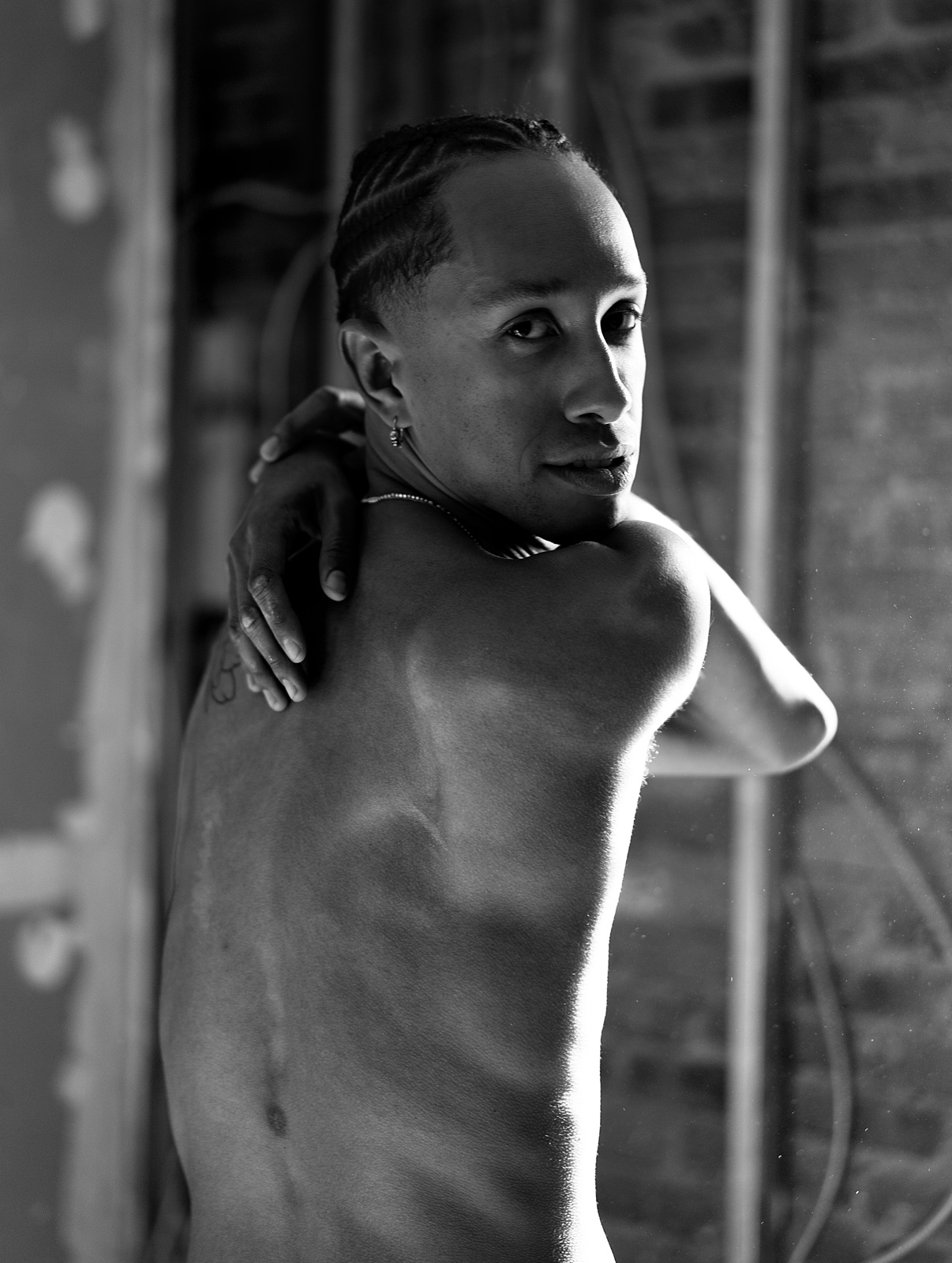

For Greenberg, this devotion has taken radical forms. In his 2020 performance OYSTERKNIFE, he walked on a conveyor belt uninterrupted for a full 24 hours; in LEPIDOPTEROPHOBIA (2020), he faced his fears head-on, trapping himself in an acrylic box as live insects crawled over him; in Admiration Is The Furthest Thing From Understanding (2021), he lay blinded as sugar syrup dripped down from above, crystallizing over time to impair his movement; in HAEMOTHERAPY (1) (2019), he invited the audience to contemplate his body as a living sculpture, balancing nude atop an altar of raw meat and spices for as long as his body could tolerate. By challenging his own physical and mental limits, Greenberg arrives at a sense of internal clarity that can be found in no moment but the present: a space of heightened consciousness, where the monotony of the everyday falls away in the face of what he terms a profound “inner silence.”

Marina Abramović is no stranger to this sensation. Widely considered the mother of performance art, she has utilized her body as both object and subject throughout her five-decade career, often leveraging acts of extreme danger, pain, and endurance to complicate the relationship between artist and audience. She’s been stabbed with knives, set herself on fire, and flung herself against cement pillars; in one early performance, Rhythm 0 (1974), she entrusted museum visitors with her life, inviting them to do whatever they desired to her body as she lay prone on a table for six hours surrounded by 72 instruments of her choosing—including matches, lipstick, saws, nails, and a loaded gun, which at one point was held to her head. In her renowned retrospective at MoMA, Abramović staged a performance called The Artist Is Present (2010) where, seated across from an empty chair for eight hours a day, she locked eyes with thousands of strangers in an act of silent communication—one that moved many participants to tears and, unbeknownst to her, served as Greenberg’s introduction to the world of performance art when he visited the exhibition at the age of 12.

“[The show] was partially what gave me permission to think about what I can do with what I have already—my body,” Greenberg recalls. It’s a concept they have since explored together, having struck up a friendship after Greenberg attended Abramović’s Cleaning the House workshop, a method of teaching she developed to hone the physical and mental fortitude required for long-durational performance. “It really works on your transformation as a human being,” Abramović states. “Time stops existing, there is no past and future—whether the performance is one hour, two hours, even a week, you have to surrender to the extending of this moment now into forever.” Greenberg agrees: “There is something so romantic about this total devotion to an idea,” he muses. “It’s a bit like love—the romantic nature of dying for art over and over, a little bit more every time.”

Marina Abramović: Let me ask you a question that I ask myself often, but have never actually asked anyone else. Why is it that younger people have such a strong response to my work [compared to my own generation]? You are from a younger generation, so perhaps you can answer.

Miles Greenberg: I grew up immersed in technology, so any work that’s interfacing directly with real life and in such a strong way is almost foreign to me, and it impacts me harder. I think it’s why a lot of people in my generation are attracted to things like sculpture. My reflex is to go into the real, into the flesh and the blood.

At the end of your show in MoMA, there was this piece: a bed of stone, with something like a pillow. I remember lying down on this for what I thought would be maybe 30 seconds, and I closed my eyes for the first time after seeing all of this work. When I opened my eyes again, it had actually been about 25 minutes, and there was a very long line of people in front of me waiting to do the same thing!

Lying there, I lost all sense of time and processed information in a way that I had never processed information before. It was very interesting to have this moment of rest and repose, as someone who had never had this silence.

“People think that performance artists are very severe, and we’re not. I think if we are, then we’re not good at what we do.”

Marina: During The Artist Is Present, I asked people to totally block off the sound around them with headphones and go to the platform and stand there in silence, for as long as they wanted. And I saw this little boy who was coming after school every single day for months.

When he first arrived, he put the headphones on and he said, ‘The headphones don’t work.’ I said, ‘What do you mean “don’t work”?’ He said, ‘There’s silence: nothing coming out.’ I say, ‘Exactly, this is what silence means.’ And then I never talked to the kid again—he would come with his parents, his parents would leave, and he would just stand there in silence with the headphones on. I noticed there were more and more kids coming to my performance, coming and putting on headphones and not listening to anything. They said, ‘We never heard the silence before.’

Camille Sojit Pejcha: You both utilize temporality in long-durational works. What do you share in your experience of time during a performance, and where do you diverge?

Marina: When you start a long-durational performance, you can’t think of time—if you think of time, your concentration is zero, you’re completely lost. Because then you’re obsessed. How long do I still have to perform? How much time has passed? When does it end? You have to totally abandon the feeling of time.

Time stops existing, there is no past and future—whether the performance is one hour, two hours, even a week, you have to surrender to the extending of this moment now into forever. It needs to become life itself. It really works on your own inner transformation as a human being.

Miles: I could not have said it better myself. It changes the structure of your brain to even approach time in the way that you have to in a long-durational performance situation. That’s why I’m also really fascinated by this onboarding and off-boarding process: how you transition between everyday reality and the parallel reality of performance.

People ask me if I meditate constantly. I actually don’t, because, for me, it’s better to go in cold and experience the sort of transcendental turbulence, like taking off in an airplane, of getting into that space and having that be legible [to the audience]. I think that’s something that people really connect to, seeing the human beings sort of transformed through this process. Whatever you’re experiencing, you have to dedicate yourself to it completely. It needs to feel like it’s going to be the rest of your life, because that’s the only way that you can abandon time.

There is something so romantic about this total devotion to an idea. It’s a bit like love—the romantic nature of dying for art over and over, a little bit more every time. Pushing against death in this way gives it a sort of form, a sense of beauty and poetry.

Marina: What do you think about how the public merges around you in support of your work—to become like a living body?

Miles: It’s interesting to look at the audience like a living body. I work a lot with contact lenses, so I actually don’t see them most of the time. I can feel them though, and I can see these shadows that sort of converge around me. I notice when people stay for five hours. I’ll be spinning on this stone at two rotations per minute for seven hours, and then I’ll come back and realize, Oh, that’s the same shadow that’s been standing there. I like that people can kind of get obsessed, and [their presence] sustains the shape of it. My relationship to long-durational performance actually started because I wanted to make something that was not theater—something people could feel free to interact with like a sculpture, to walk in and out of whenever they want.

When you give people that freedom, I think they get even more intrigued, because they’re like, ‘Why am I not sitting down to see this from the beginning to end—what is going to happen? Why should I be allowed to come in and go into this reality whenever I want?’

Marina: To me, it’s so important to give the audience freedom. In the early ’70s, it was a different structure: People go there and sit and look at a piece, and become bored after some time, and then you feel incredible pressure and shame to leave because somebody will see you leaving. They will stay if they don’t even like the work, and they hate you for it.

I remember when you were doing your 24-hour performance OYSTERKNIFE, and I would come there in the morning, first thing, before I even brushed my teeth. I had to see what you were doing. And at one point, you fell down—you lost consciousness. Your mother was calling me, asking what we should do—Should we get a doctor? I said, ‘You’re forbidden to do anything. Everything that happens is part of the piece. Let it go.’ And she did.

I was very proud. In entering the performance space, there are different rules and different limits. So anything that happens is a part of the piece. It is something we can’t predict.

Miles: I’m so grateful you stopped my mother or anybody at the museum from dumping water on my head, because I think I would have been miserable. It was only 22 minutes of unconsciousness. So, you know.

“Time stops existing, there is no past and future—whether the performance is one hour, two hours, even a week, you have to surrender to the extending of this moment now into forever. It needs to become life itself.”

Camille: Performance art demands this sort of presence from the audience, by merit of the performer being so present in their body—something young people are prepared to embrace, as Miles said, having been accustomed to existing in ephemeral spaces like the internet. I’m curious what you think about the role of emerging technology in performance.

Marina: Recently, I got an email from somebody asking if I can make an NFT of my soul and sell it on auction. I get the most strange, strange, strange emails. Once, I got a contract from [an artist’s] lawyers. She [would] like that I agree with the lawyer that after my death, before the funeral, she would massage my body—my dead body—for one hour. Another time, there was a collector who told me that he liked my work so much that he wanted to give me [the entirety of his] possessions when he died.

I’m really open-minded. I’m not one of these old artists who hates everything which is new. Just the opposite. But I don’t see any NFTs I’m really moved by, and I don’t have any great ideas yet myself. If I have one, I will do it.

Miles: Having grown up surrounded by technology, there are so many options at my disposal. Personally, I feel like the only good art that I’ve ever seen necessitates its medium. That is doubly true for technology. It’s very important that the work you’re making relies entirely on how you’re making it. It’s very important that they correspond: the idea, and the means, and the process. If I’m looking at a VR piece, and I say to myself, This could have been a video, or This could have been an animation or a projection… Well, there’s no reason for it to have been [VR] then, you know?

There’s one crypto story I’ve heard that I actually quite liked. This man in Quebec was mining bitcoin. That process uses a lot of energy, which is usually wasted. All of the servers used to process this data create an enormous amount of heat, and because it gets so cold here, he made a deal with a small church, and basically used their basement as a server room in exchange for providing free heating for the church in the winter. I found it very interesting to look at it in this way—of, like, using every part of the technological process, making something from the waste.

Marina: A perfect recycling.

Honestly, what I think is so discouraging, is every time people call me and ask me to [make an NFT], they always give the example of how an NFT sold for $69 million. But money was never the reason to do art in the first place, you know? I am tired of artists becoming commodities.

I always mention the wonderful book, Just Kids, by Patti Smith. They’re talking about New York in the ’70s, and how it was so incredibly difficult to live day-to-day. There was no money anywhere, and they were still making art, because they believed in it. Art was never [the route] to becoming rich, or famous. To have commodities, or millions in investments. I don’t know, maybe call me old-fashioned, but to me, art is the oxygen of our society. Its benefit can’t be measured in money, commodities, or investment. These are the wrong reasons [to make art].

Miles: I think money has made this whole conversation around NFTs really boring. I think there’s great art to be made with these mediums—but it hasn’t happened yet.

Marina: It’s very important to look in the past sometimes, to learn about the present. When the video camera was invented, everybody was first like, This is ridiculous, this is not art. A lot of bad artwork was made with this video camera. [They were] trying all kinds of stuff.

Then came Nam June Paik, who created incredible artwork, [with his television sets]. He brought the entire idea of using video [in art] to a totally different level. Video became art. We need time for NFTs. Sometimes, we just need time to pass. That’s all.

Camille: What have you learned from witnessing each other’s work take shape across various mediums?

Miles: I’ve learned so much. We did the Cleaning the House workshop—the Abramović method in Greece. Five days of no eating, no speaking, and doing these exercises.

It was really fascinating, because it was the first time that I was able to truly create a perfect environment for the direction of my thinking, when it comes to space and rituals. Marina has—through her work, and through direct teachings—given me an enormous amount of context around the impulses that I think a lot of my work comes from, and [taught me] how to put that into physical space with very little more than what we’re born with. And that’s really exciting to me. It has given me permission to basically have a career and have a practice with what I have. I think that the most important thing that Marina has taught me is that I have everything that I need. ‘Of less and less,’ that was my favorite line.

“It doesn’t matter if it comes from fashion, from cinema, from astronauts, from science, from art. There are people who are inventing, who invented a different vision of the world, and the ones who follow.”

Marina: I’ve had a long career—it’s been 50 years now—and only in the last parts of my life have I really understood the importance of long-durational work. So it was such an incredible surprise that Miles, who is so young, understood this immediately, from the start of his career.

He came to the idea of long-durational performance [on his own terms]—allowing him to actually create his own system of work, which is truly original and independent. When I’m looking at his work, there’s no similarity between his work and my work. This is something that people want to say, but his sources come from his own background and his own mind—a young mind, creating for a different generation. So I learned from him. I can give him experience, but he actually gave me the possibility to be in touch with the time we live in now. That’s a connection that I think is so important, so it’s a very fair exchange. He takes the advice, but he always makes it his own. He created his own style and his own way, and it is really truly respectable. This is why I am having this conversation today. Miles is just in the beginning of his career and the things he has done are mind-blowing—there’s never a moment that he doesn’t surprise me.

Our friendship comes from the grounds of mutual understanding. We just went recently to see this very, very old Iranian movie together. It was strange. It was boring. It was interesting. It was curious. It was mysterious. It was everything. And we both went with an open mind—he has a young open mind, and I have an old open mind. But we both have an open mind. This is our connection.

Miles: I like that we were able to laugh at all of the moments where people got shot, and then stayed alive for a little bit too long.

Marina: Sense of humor is very important.

Miles: People think that performance artists are very severe, and we’re not. I think if we are, then we’re not good at what we do.

Marina: Absolutely. If you put a group of creative people together, we don’t talk about work, we have fun. It’s a different story. Life is short, and we have to enjoy every minute!

In one week I will be 75, and I just went to TJ Maxx [for the first time] and bought what I am wearing for this interview, on sale for $11.94. It comes with matching pajama bottoms. I mean, this is ridiculous, but I love it.

I have learned to never stop learning. It’s very important at my age to be curious, to have a mind like a child, to see everything for the first time. This is what I do: I open my eyes.

Camille: How do other creative mediums intertwine with and inform your practice as artists?

Miles: I wanted to be a fashion designer before I wanted to be an artist. I started out really wanting to be a couturier. The worlds and the universes that Alexander McQueen created were everything to me—not just the theater of it, but the autonomy that the models and the visuals had. Eventually I realized that performance was more of a concise avenue, because I’m terrible with a sewing machine. [Laughs]

Marina: When the designer Riccardo Tisci and I met, we became good friends. We started thinking about things, how fashion is inspired by art [and vice versa]. I said to him, ‘Fashion feeds from art—and if I’m art, you’re fashion: Suck my tit.’ So we made a piece together titled The Contract: an image of me holding him [in my arms] while he sucked my tit. It was a really wonderful collaboration and [an important] friendship.

I felt like in the ’70s, there was an idea that if you care [about your appearance] you’re a bad artist because you try so hard. I got so fed up with this attitude! I remember after walking the Great Wall of China, I woke up one morning and said, ‘I don’t need to prove anything to myself. I’ve done my work,’ and I went out and bought my first [Yohji] Yamamoto suit with the money I got. I remember coming out of the shop with the Yamamoto suit, feeling great, and realizing it’s not the fashion that wears me, I wear the fashion.

I think of Yamamoto in the ’70s—at the time he was so popular, and everybody was asking ‘Why are these pieces so large?’ He said something like, ‘Oh, because I like that between the body and the fabric the spirits have space to live.’ I thought, Shit, this guy really thinks about spiritual stuff! I divide the entire world into two sections: the originals, and the ones who follow. It doesn’t matter if it comes from fashion, from cinema, from astronauts, from science, from art. There are people who are inventing, who invented a different vision of the world, and the ones who follow.

Hair Erol Karadag. Make-up Rommy Najor using Furtuna Skin. Production Director Madeleine Kiersztan at Ms4 Production.