For Document’s Winter 2021/Resort 2022 issue, the musicians discuss the need for constant reinvention, growing up online, and why comfort doesn’t make for good creative work

“The internet was escapism to me when I was younger,” says Charli XCX. “I got obsessed with photos from parties in Paris or London, or places I felt I could never get to. It was totally escaping from my normal countryside life [in Essex, UK]. Myspace was where I would go to watch people live lives I found more interesting than my own.”

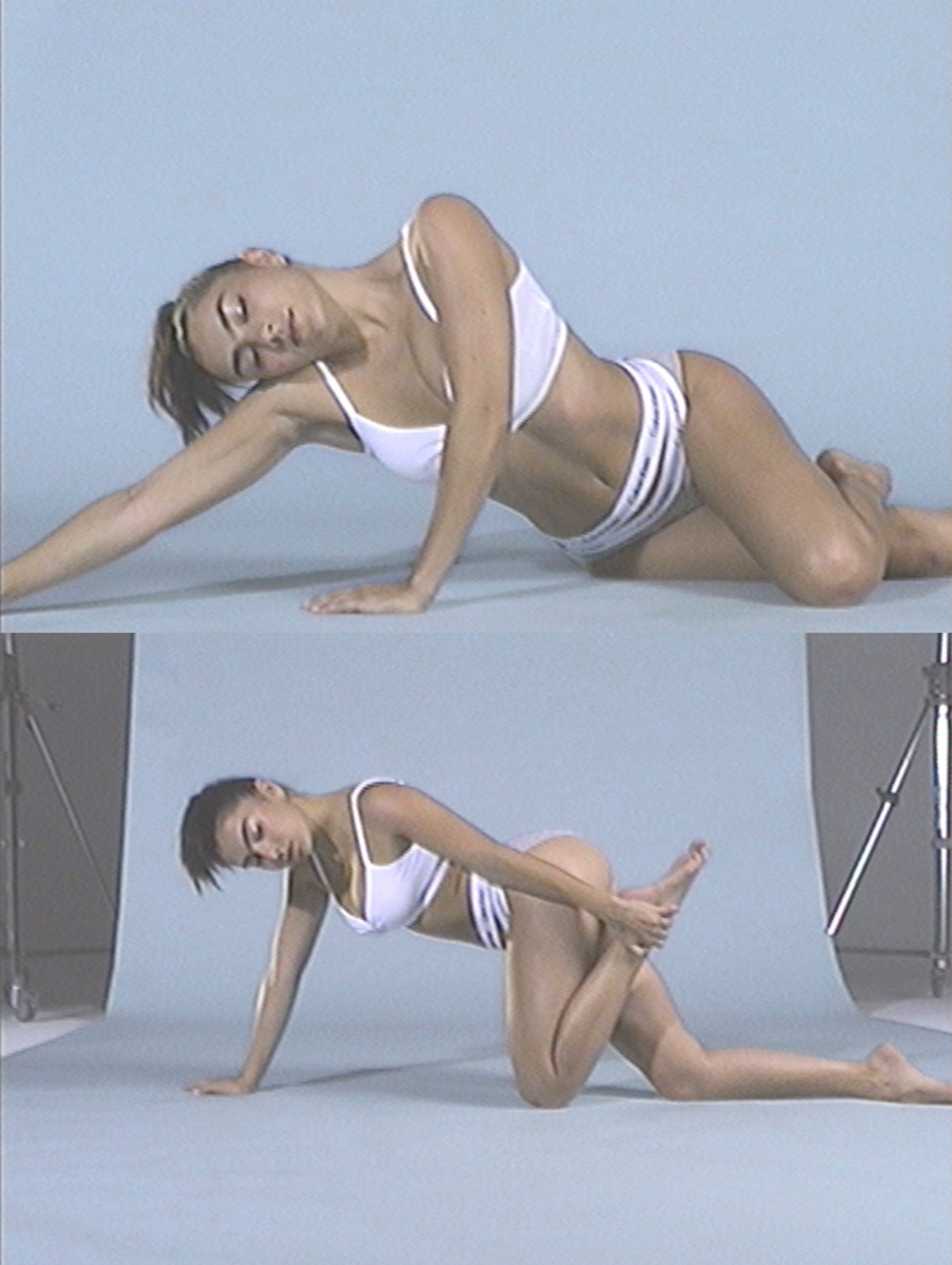

It was also her ticket to creating that kind of life for herself. After releasing songs on Myspace in 2008, she soon gained the attention of club promoters and began performing at illegal warehouse raves in London as Charli XCX, a musical moniker deriving from her screen name on MSN Messenger. Now she’s at the cutting edge of pop music, having bridged experimental and mainstream sensibilities to create a sound all her own—one that has transformed time and time again, from her pop-punk beginnings to the experimental electronic stylings of her second EP, Vroom Vroom, to her recent foray into classic pop songwriting on her forthcoming album Crash. While Charli’s signature hooks and emotive songwriting evoke a sense of continuity, her pursuit of stylistic reinvention has been constant—a drive she attributes to her own hunger for challenge and novelty in all aspects of life. “Perhaps it’s a bit self-destructive when it comes to my personal life, but when it comes to creativity, I don’t think constant comfort makes for consistently good work,” she says.

The drive to embrace transformation is one she shares with electronic musician and producer Daniel Lopatin, better known as Oneohtrix Point Never. His sound has undergone several metamorphoses over the course of his career, from the deconstructed plunderphonics of Replica and R Plus Seven, to the heavy metal influences of Garden of Delete, to the symphonic cinematic scores he composed for the Safdie brothers’ films Uncut Gems and Good Time. His prolific career was recently commemorated in an audiovisual anthology, Magic Oneohtrix Point Never (Blu-ray Edition), which showcases his past eight years of creative output across art, film, and animation.

Lopatin’s mesmerizing soundscapes are rich with recontextualized samples that reify references from years past, evoking the relationship between sound and memory to become music that eludes definition. “I was always into the buried treasure aspect of the internet,” he says. “[Growing up] I was extremely online. I liked to dig through the trash and find something special there, and I still do.” One such example is Chuck Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1 a 2010 side project that has since been credited with the invention of the internet-based genre vaporwave. Released under a one-time pseudonym, Eccojams sees Lopatin sample micro-excerpts of ’80s and ’90s pop acts to create a unique compositional style; the album’s artwork, which draws on graphical aesthetics from the ’80s, incorporates fragments of cover art from the Sega video game series Ecco the Dolphin.

In the years since they began making music, Charli and Lopatin have both redefined what it means to be “experimental” on their own terms. “For me it’s about not falling into a pattern, not repeating what’s expected of me,” Charli says. “I think a lot of my fans saw my early music as a rejection of the major label system, but it was more a hope of what pop could be—how challenging it could possibly be.” Lopatin agrees, noting that what is subversive changes in step with the musical landscape and one’s own artistic canon. “Experimental isn’t a sound or difficulty level attributed to comprehending some piece of art,” he says. “It’s an attitude of bravery in the face of market-generating clichés from captured old braveries.”

The pair first met at Charli’s home, where they sat on the floor and talked about love–a prevalent theme in Crash, which sees Charli and Lopatin collaborate for the first time. The two musicians join Document to discuss embracing change, rejecting the limits of genre, and why house parties are a staging area for creativity.

“I had felt that a pattern was beginning to develop within my music, where fans knew what to expect, and I wanted to break that pattern.”

Charli XCX: Hi king. How are you?

Daniel Lopatin: I’m in the Big Apple, baby.

Charli: I’m also in the Apple. The Big one.

Daniel: Should we start? Let me get my little notepad out.

Charli: [Laughs] What a pro! I thought we had started already.

Daniel: Well, it’s a nice segue actually. How long have you lived in Los Angeles? Do you think being situated in the States has shaped you aesthetically?

Charli: I bought my first place in Los Angeles in 2015. It was quite spontaneous because, even though I’d been traveling through the city a lot, and had been working there on and off for a while, I hadn’t really spent time there. Like, time doing nothing, wandering around, feeling it out—the stuff you generally do when you move to a city or fall in love with a place. But I did it, and the house I moved into was actually quite comically British—an old, dark wood, mock-Tudor place. Everyone said it was haunted. I threw a lot of parties at that place from around 2015 to 2018, and at those parties I met a lot of people and collaborators. People would literally come to the house and not know whose place it was. It was a little Gatsbyesque, but more trashy.

Obviously, partying is a constant theme throughout my music, and not really in a vapid way, in my opinion—although sometimes it’s vapid, I guess. I discover more about who I am and what I feel at parties than in most other life situations. And so those years probably really affected me and my music, and I think it’s no coincidence that those were the years when I really shaped and developed my sound into something truly unique. LA probably had something to do with that—the people who were there, the escapism, the freedom the city provided me…

I still love [LA]. I moved house. You’ve been to my new place, I think, for the party we threw after Caroline [Polachek’s] show at the Greek [Theatre]. [Laughs] So I guess I’m still partying. But it feels a little different now, a bit more calm. I don’t know, there’s something about the atmosphere of an LA house party that still feels really weird and foreign and fascinating to me. It inspires me.

Daniel: No, I agree! Somehow even as an introvert—or especially as one—I find that a party is kind of a staging area for creativity, the gift of gab, laughter, and revelry. We laughed, we cried! And music is so linked to revelry and escape, in such a massive and historical way—it’s practically the job description.

Charli: Yes, totally. I mean, we met for the first time at that party; we sat on the floor in my living room at 2 a.m. whilst everyone else was in the pool, and it sort of felt like a film scene or something. I think we were talking about relationships—nothing too mind-blowingly profound, but the setting alone and the atmosphere of the party made it feel sort of grand to me. I’m not sure if you felt the same, but that’s my interpretation of it.

Daniel: Yeah, it really stuck with me—the house, and seeing you move fluidly around and check in on everyone’s vibes. It was somehow very touching. And we had really deep convos right away on the rug. Like a mound of friends talking about love and loss.

Charli: Yes. It was beautiful. Do you throw parties ever? Are you a party guy? By the way, if there’s a delay in responses, it’s because I’m just getting a vitamin drip put in my arm.

Daniel: Ooh, I want to do that. I’ve been staying in LA for a bit, and have a house to myself, and I finally decided to grow up and host a Thanksgiving this year, which was awesome. We brought one of the studio monitors and a little mixer up, and made a karaoke station. Potluck dinner. Chorus of friends’ voices, old and new. It felt very nice. I’ve always been a little bit reclusive—but it’s changing, as I get up in years. The lone wolf thing has lost its luster. We were already becoming so ‘networked’ prior to the pandemic, which felt increasingly terrible. And then to be separated by some state sanction, becoming even more online… There’s a more genuine want for contact.

Charli: Gross! You’re connecting with people and finding love and warmth in your life!

Daniel: Yuck! Okay, I have some questions about style for you, which I think about a lot with your music.

Charli: Go for it! The drip’s rocking [shares picture of vitamin drip].

Daniel: Look at that massive bladder of drip.

Okay, well let me just say, a track like ‘pink diamond’ goes deceptively hard [stylistically]. You’ve always had this industrial, almost EBM thing happening in some of your music, ‘Vroom Vroom’ being one of the finest examples where it feels like the sensuality and brutality of the textures is on full display. What’s your relationship to electronic music? Because I sense you really are into pretty profound textures. Do you have a love of machines?

Charli: [Laughs] You know, what’s funny is I’ve never thought about it. Obviously, a lot of my collaborators are into machines, technology, the conversation between their music and texture. It’s not something I care to acknowledge when I think about my music—but yes, it’s undeniably there.

Daniel: You just like hanging out with the machine people, we’re a convivial bunch.

Charli: I think what it is, is that those sounds you’re referencing make me feel more. And it just so happens that a lot of those sounds are more aggressive, textural, and jarring—but often paired with something lush or luxurious.

It’s interesting because I really sit on two ends of the spectrum when it comes to sound choice. Sometimes it’s about the idea of being purely obnoxious, because it’s fun to be a major-label female pop star and have a song like ‘pink diamond’ be track one on your album.

Daniel: Yeah, bratty!

Charli: But on the other end is pure beauty. There’s a beauty in those sounds to me. They make me feel more than a stereotypically ‘emotional ballad.’

Camille Sojit Pejcha: Charli, your musical moniker goes back to your MSN Messenger display name, situating you among a generation of musicians raised with access to the internet (and all the sound samples that come with it); Dan, your work has helped to inspire emerging internet-based genres like vaporwave. What was your personal relationship to the internet growing up?

“I was always into the buried treasure aspect of the internet; I liked to dig through the trash and find something special there, and I still do.”

Dan: I was always into the buried treasure aspect of the internet; I liked to dig through the trash and find something special there, and I still do. It’s only ever helped me to have access to history and hear as much music as possible.

[Growing up] I was extremely online, but not so much anymore. I cherish my time offline, more now than ever, with the world becoming so networked and flat.

Charli: I mean, I’ve always thought so. I’m kidding! Don’t print that! [Laughs]

The internet was escapism to me when I was younger. Myspace was where I would go to watch people live lives I found more interesting than my own. I got obsessed with photos from parties in Paris or London, or places I felt I could never get to. It was totally [a means of] escaping from my normal countryside life [in Essex, UK].

Daniel: We’re both making music that has a sort of ‘online’ affect, which demands [that the listener] be re-enchanted with sensuality. So there’s this kind of weird desire to go over-the-top sensual, at least for me.

Charli: Your music reminds me of Disney, especially [your new album] Magic Oneohtrix Point Never. Maybe that was intentional—I feel like there were some font connections in some merch I saw?

Daniel: No, it’s real.

Charli: To clarify, I mean this because of the luscious sounds. The way Snow White sings in the Disney movie, that sounds like your record. Did you produce Snow White?

Daniel: [Laughs] Well, this is sort of why I always felt a kinship with Tim Burton, basically—there’s something about Tim Burton’s worlds that felt both cartoonish and comically melancholy. And in fine art, people like Jim Shaw, Mike Kelley, et al.

Without going into some heady screed, I love cartoonish forms. And I love seeing them kind of abstracted, forced to live normal lives, but still so spacious and lush at heart. I see some parallels in our work this way.

Let’s talk about your last couple singles, ‘Good Ones’ and ‘New Shapes.’ These are different beasts! They have the architecture of mid ’00s smash records—anthemic power pop hooks, clean lines, big vocal melodies—but are much more straightforward than your more experimental side. It’s so exciting to see you do both things so well, so consistently, throughout your career. It’s really inspiring.

Was it an urge to write in that mode again?

Charli: Yes, honestly. I had felt that a pattern was beginning to develop within my music, where fans were sort of beginning to expect something from me, or knew what to expect, and I wanted to break that pattern.

Daniel: That type of song presents an entirely different challenge. It’s less about production style, and really about you as a writer and performer. It’s hard to be vulnerable that way, on your level especially.

Camille: You’ve both worked at the fringes of more ‘mainstream’ genres. I’m curious how your own previous output, and trends within the broader musical landscape, influence what you feel is new or challenging for you personally.

Daniel: Traditionally, experimental music was tied to academic music and emergent technology—it was literally lab-based. My definition is more just an approach to being creative. I never thought of myself as being all that experimental. I just wanted to make stylistically ambiguous stuff that had a lot of disruption in it, but still moved through time like narrative music. And that really hasn’t changed all that much.

Charli: As pop in general begins to morph into the more ‘experimental,’ I’m sort of interested in pushing it back to something more traditional. I think a lot of my fans saw ‘Vroom Vroom,’ and Number 1 Angel, and Pop 2, as a rejection of songs like ‘Boom Clap’ and ‘Fancy’—or a rejection of the major label system. Which maybe it was for a second, but really, it wasn’t. It was more a hope of what pop could be—of how challenging it could possibly be.

Daniel: That’s what pop means to me, at its best. You’re not reactionary that way, I don’t find. You seem to love it all.

Charli: I do. That’s the thing—I love pop music. I’ve never wanted to reject it, really, apart from when I feel scared or threatened, but that’s become less as I’ve gotten older. ‘New Shapes’ and ‘Good Ones’ are celebrations of me getting back to what I feel is more ‘classic’ pop writing.

As major label artists crave to be more ‘real’ and ‘authentic’ and ‘involved’ and ‘left,’ I’m more interested in playing with the narrative of the opposite. For example, I didn’t really write much of ‘Good Ones’—I essentially took it as a pitch song, because I wanted to be a stereotypical, classic, major-label pop star. It was fun to play that game, but probably only fun because I know I can write a huge pop song. Does that make sense? I like seeing the whole thing as an art piece sometimes—it’s the ultimate version of playing the game.

Daniel: But to me, that is genuinely experimental; experimental isn’t a sound or difficulty level attributed to comprehending some piece of art. It’s an attitude of bravery in the face of market-generating clichés, from captured old braveries.

“Whenever I get comfortable, I can sit in it for a minute, but I soon have to make some kind of drastic switch. I don’t think constant comfort makes for consistently good work.”

Charli: Only truly fearless people get that. Most people are afraid to play with that world out of fear of being labeled ‘inauthentic.’

I think for me, it’s about just not falling into a pattern—not repeating what’s expected of me. I find this happening within my personal life, too. Whenever I get comfortable, I can sit in it for a minute, but I soon have to make some kind of drastic switch. Perhaps it’s a bit self-destructive when it comes to the personal life side of things, but when it comes to creativity, I don’t think constant comfort makes for consistently good work.

Daniel: People hated it when I started doing more traditional songs on my records, because they were fixated on the songs lacking something they were actually just used to, which I didn’t feel like regenerating just because it was effective. It would be like Hollywood making 10 sequels—what’s experimental about that?

Charli: Exactly. Consistency isn’t that exciting, hence Madonna and Bowie and Prince being ‘the best artists’ [in their heyday]—they were constantly changing and challenging and not always making sense in the moment.

Daniel: Amen.

I wanted to ask you a more personal question, to end on: Are you able to lead a somewhat straightforward life in the face of your popularity? You seem so grounded to me, but I’m sure there are moments when it’s just simply not ‘normal,’ and never will be. How have you found your rudder? It seems really apparent that you’re very comfortable in your life.

Charli: You know what, I am. I really believe you attract that stuff, if you want it. There are times where I want it, I attract it, and I get it—and then [there are] times I don’t want it, I don’t seek it out, I become less public-facing, I hide, and I don’t get it.

Daniel: I think it is a bit alchemical and karmic in that way. You put a certain energy into the world; certain paths open up magically.

Charli: Obviously, people who have fame on a larger scale don’t get that choice. But where I’m at, I still have a choice—which I’m very grateful for, because it’s quite a rare spot to be in.

Daniel: It’s important to recognize [that fame] hasn’t simply happened to you, but that doesn’t make it in your control either. It’s a dynamic thing.

Charli: Sometimes I’m very comfortable, and sometimes I feel totally unbalanced. But I’m lucky that my friends, my collaborators, the people I surround myself with—we are all like-minded. I think we all help, and support, and ground, and lift each other up when necessary, and it sort of creates a nice dynamic, as you say.

Daniel: My shrink said to me the other day, ‘Surround yourself with high-quality people,’ which is one of the only times he’s ever really given blatant advice. [Laughs]

Charli: I love it when they commit to a statement. It’s always a moment!

Daniel: I know. I was like, ‘Admin reveal!’

Okay, thank you so much for this conversation. I feel refreshed somehow, and I didn’t even get the drip.

Hair Franziska Presche at Together. Make-up Mathias van Hooff using Make Up For Ever at M + A Talent. Manicure Michelle Humphrey at LMC. Set Design Hella Keck at Webber. Photo Assistants Rory Cole, Ed Phillips. Stylist Assistants Brigitte Kovats, Elisa Juesten. Make-up Assistant Shiori Kawato. Shoot Production 360PM. Production Director Madeleine Kiersztan at Ms4 Production.