In their new book 'At Night Gardens Grow,' Guilmoth reconciles their own inner world with their surrounding landscape

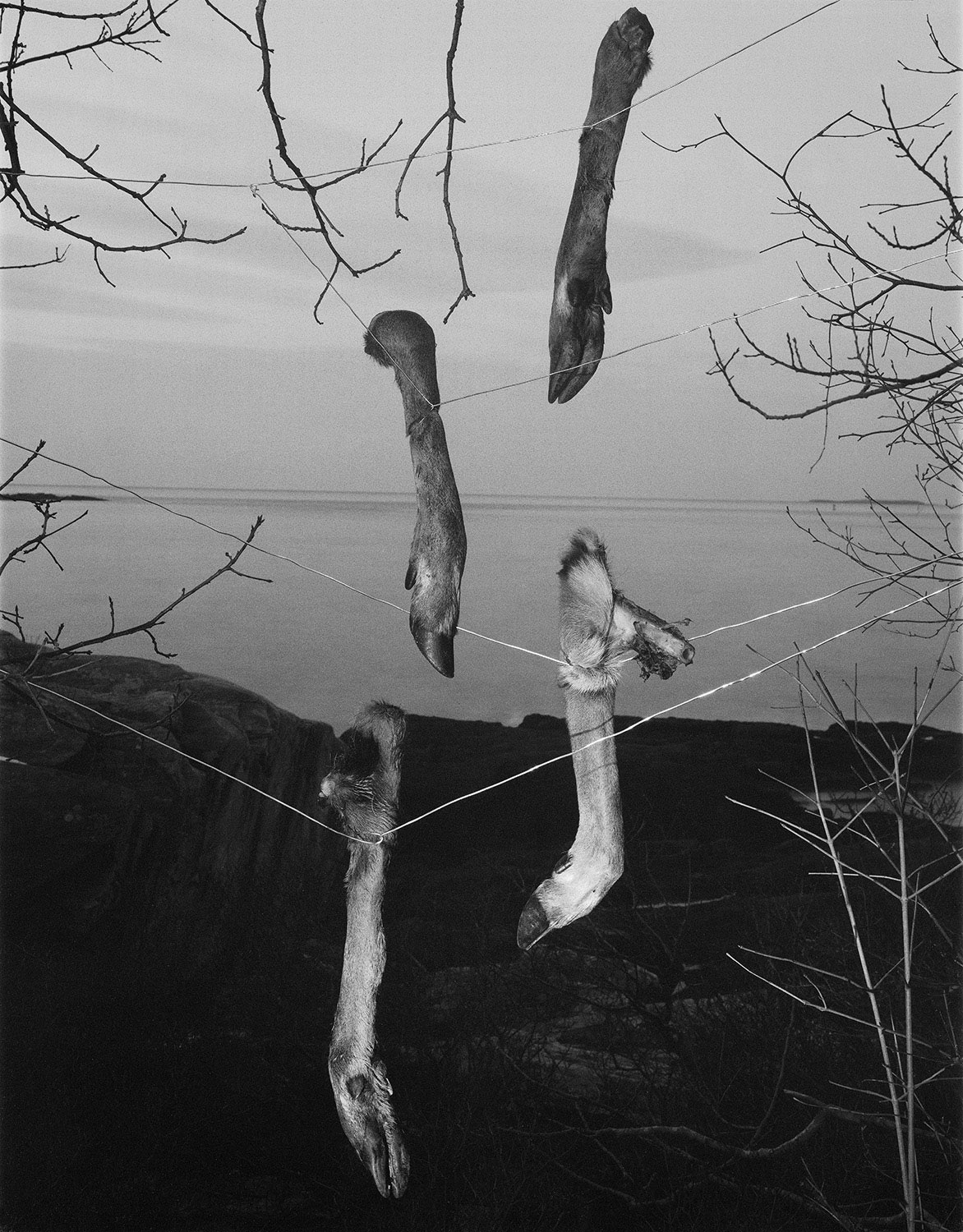

Paul Guilmoth is a photographer who lives in both the United Kingdom and New England. In their 2021 monograph entitled At Night Gardens Grow, published by Stanley/Barker, Guilmoth constructs a psychically charged narrative that creates more questions than answers. Their work, shot in black and white and primarily on large format, creates a mythical portrayal of a landscape and its inhabitants that feels as looming as it is arresting. The work is a means for Guilmoth to experience the landscape in a new way, but also as a means for escapism. While the images themselves are an assertion of the mortality of those they depict, Guilmoth creates them from a place equal in apprehension and joy.

Olivia Noss: In the synopsis of this book, it states this work is, “an elegy to a queer world that rests between the personal landscapes of home, and the ubiquitous terrains of identity.” I love the idea of identity existing as terrain, particularly queer identities. Could you speak more to this?

Paul Guilmoth: I’m realizing my brain is progressively at odds with my body. The androgyny of my mind is slipping further from being able to agree with my biological assignments/limitations. Just as with my photographic practice, I find myself constantly trying to reconcile my inner world with my outer landscape (my body/the world) to achieve something close to harmony. I use photography to build a world I can escape to.

I’ve been curious about what queerness can look like without a human body present. How do I photograph that?

Olivia: You explain that photographs can function as epitaphs, and that the permanence of photographs gives materiality to loss. Would you say that photography is a form of constructing a past on your own terms, knowing loss is imminent in many ways?

Paul: In relation to my process, the portraits I take encapsulate a place (home) and loved ones. Each photograph is a death in that it becomes the physical matter of a moment that won’t exist again, or a face that you might not ever see again, or a field that’s been bought and built over. The concept of mortality is nowhere near as palpable as a photograph of someone’s face. I am so terrified of losing the people I love.

I think most photography has a hard time existing in the present. Because I work in film, by the time the photograph is taken and developed, the passing of time seems exaggerated and tactile. Because I’ve formed a relationship with the people and the places in my photographs, [many of whom I’ve known for a long time], the history we share together [when I take their portraits] inevitably looms over us and guides us. In a way, the present is unattainable.

Olivia: Your work has been said to be a testament to the power of the myth. Could you talk more about myth functioning as a lyrical device that motivates your work?

Paul Guilmoth: I can’t retain names, places, or stories very well at all. I have really resigned myself to learning things in a different way: through the way things appear and the emotional responses I receive. I’m not interested in specific myths, theories, or stories. I’m intrigued by the vague impulses that cause people to create stories and the fluid worlds that form from those impulses.

I don’t care about folklore as a discourse in a way that has me doing research or intentionally trying to tie in specific historical narratives. Instead I focus on what I know can be photographed: my neighbors and my immediate surroundings. History, and myth find their way into my work by me simply existing in a place and using it as the setting for my photographs. It’s very important to understand the actual history of the place you inhabit (who utilized it and lived there before you, extending back to colonization) and what, as a white person, it means to be living and making work there.

Olivia: In that vein, you mention that truth in photography relates to humanity and relatability, and less so with integrity. Rather, truth has more to do with intention than a resulting image. This is a really interesting angle through which to look at truth in photography, especially given how literally the truth is taken within a medium that aims to document. When did you begin to think about images in this way?

Paul: I think there’s many different kinds of truths in the world. When I see a photograph I can instantly relate to, even in the most vaporous or distant kind of way, I know it contains a truth.

Someone at my recent signing told me the new book was ‘filled with so much humanity.’ I really like that sentiment as a lot of people see the night time, or the tonality in my work as solely relating to the dark, sinister and brooding things of this world, which is not true for myself. Yes, there are bits of the gothic in my work, especially in it’s stylistic treatment, but I also find a lot of joy in night-time, and in my relationship to the place I live, work, and photograph. For myself the work is filled with equal parts joy and dread.

Olivia: You have described your images as a ‘manipulation of landscape’–what do you mean by that?

Paul: The manipulation comes from a loving and respectful place, I believe. They are delicate acts of gathering matter, and building things that are not meant to last. Often I use my photographs as a cloak: I want to see the place I live, but in a way I’ve never witnessed it before. I want to imbue a sense of magic that sometimes gets lost in the common, day-to-day ritual.

Olivia: You consider this work to be autobiographical, documentary, and fictional. What would you say it is mostly?

Paul: For a while now, I’ve felt weird about using the word fictional in regards to my photography and I’ve tried to understand why exactly. I think fiction works as a concept or a literary tool, but these photographs, and any others, are real and the image itself is the evidence of that. I think they are less fictional than my memories. They’re autobiographical in the sense that it’s the only extension of myself that’s on display in a decisive, concrete way. Because my subject matter is so close to my heart, I would reckon the work teaches me about myself and my relations to my surroundings. I try to let the work guide me just as much as I guide it.

I think documentary is mostly a stylistic approach I use to make my work. It also relates to my previous statement about autobiography and in a way the two can be seen as the same thing perhaps. My work is a document of my surroundings and all of the uncertainty that exists therein.