For Document’s Summer/Pre-Fall 2021 issue, the artist joins Thelma Golden to discuss the cultural legacy of 'Jet' magazine and the love language of collage

Growing up in New Jersey in the ’70s and ’80s, Mickalene Thomas rarely saw photographs of people who represented her own likeness in mainstream pop culture. She noticed a lack of powerful imagery of Black women, aside from in the pages of magazines like Jet, Ebony, and Essence. Thomas discovered a sense of empowerment within these publications as they transformed the way she saw herself. The artist developed her practice—first as an undergrad at Pratt in New York, then while pursuing an MFA at Yale—with this goal in mind: to change the perception of Black women in society.

Thomas reverses the stereotypical role Black women have been confined to. In her 2007 painting A Little Taste Outside of Love, she references Édouard Manet’s Olympia: replacing the white European female subject, served by a Black woman, with a Black female figure who assumes the life of leisure once reserved strictly for white people. One of her first muses was her mother, Sandra Bush—a striking figure who stood at 6’1” and modeled in the ’70s—who the artist wanted to portray in such a way that her mother could view herself the way that her daughter did: as a worthy and powerful Black woman. By giving the Black female form a starring role in art history, elevating her onto the canvas, Thomas inspires others to see the beauty, power, and strength that she feels in her presence.

This fall, Mickalene Thomas will open Beyond the Pleasure Principle, an international exhibition across the Lévy Gorvy gallery’s four locations in Paris, London, New York, and Hong Kong. Spanning Thomas’s career since its beginning in the ’90s, the show features paintings, installations, and video works—from her canvases imbued with art history references, to her investigation of beauty and Black identity, to her exploration of activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the present day.

Thelma Golden, the director and chief curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem, first met Thomas while she was an undergrad at Pratt. Thomas would later participate in a residency at the institution, cementing their relationship. Thomas recently spoke to Golden about the portrayal of the Black female figure in art, the influence of Jet magazine, and the affirmative new work she created for the cover of Document’s Summer/Pre-Fall 2021 issue.

Thelma Golden: There are so many ways into a conversation with you, Mickalene. So, let’s start at the beginning. Let’s talk about when we met.

Mickalene Thomas: It was probably around 1996. I moved to New York in February of ’95 to go to Pratt, and I saw your [Black Male] show at The Whitney before it closed. I remember us meeting on the streets of SoHo and you asked me about myself. I said, ‘I’m an artist and I’m studying at Pratt,’ and you were, like, ‘Welcome.’

I just remember thinking, Oh my God, oh my God! As an undergrad in New York for the first time, I felt this synergy. It was an amazing Black bohème environment; Ellen Gallagher was having her show at Mary Boone, and I was in the middle of it all. Here I was, this girl from New Jersey via Portland, Oregon—long locks, kinda a little crunchy, kinda trying to figure it out—but being introduced [to you] and seeing the evolution of so many great artists. I chose Pratt for that reason, instead of the San Francisco Art Institute. I wanted to be in the middle of the excitement.

Thelma: I remember that moment, and I felt your energy—you expressed a full sense of your possibility. Then I fast-forward to when you were at Yale. I remember seeing the MFA show and hearing Glenn Ligon describe your works. The precision of Glenn’s eye, combined with the absolute strength of his intellect, is the way in which I understand so much about art. I remember him describing one of the paintings in your MFA exhibition and situating it so firmly within the uniqueness of your voice in that moment, but also within this larger art historical dialogue.

The moment at which we began this [ongoing] relationship of dialogue in and around your work, and the world you’ve created through your work, was when you were in the residency program at The Studio Museum in Harlem. Can you talk about that year?

Mickalene: There was a lot to unpack for me during that time as a Yale graduate, and I was encouraged to apply [for the residency]. I wasn’t going to. I think I was scared. It was a lot [to do with] the unknown, but I also wanted to move into a space where I could just make, and it was an uncertain transition from graduate school to a place where I could experiment. A good friend, Kehinde [Wiley], was an artist-in-residence, and he was encouraging me to apply, saying, ‘No, this is a place where you can experiment.’ So I applied.

I was a resident with Deborah Grant and Louis Cameron. I felt a bit insecure in relation to their experience; I knew I was worthy of being there, yet I also felt an enormous responsibility to do a great job, remembering that there were a lot of other people who had applied. I wasn’t one of those artists that left graduate school thinking, ‘My shit’s good.’ I left with the thought and feeling that there was more to learn, more to develop, more to explore. I went into The Studio Museum with this rigorous focus of wanting to become a better artist. Being [there], I understood the history and knew that I stood on the shoulders of so many other amazing artists before me. My thoughts were, ‘I need to do a lot more work because I want to be where they are someday.’

Thelma: In that moment, you began to develop the vocabulary for your practice. You were engaged in photography, collage. You were beginning to explore the idea of working with human, animal bodies. You approached ideas of scale and palette that you have developed. Can you talk about exploring these aspects of your practice?

Mickalene: A lot of the ways in which I work with various mediums started back at undergrad, then were put on the shelf when I went to Yale. That was the first time I was challenged about aspects of my work that did not deal with the self. Once I entered The Studio Museum in Harlem, I was able to explore all of those mediums freely. I began thinking about collage and its history, what that meant for me as a young African-American artist, and all the artists that had cemented the ways in which I could formalize my own compositions and concepts; thinking about scale and its relationship to my own body, and realizing the impact of the image that I wanted to create.

Discovering [the impact of scale] had to do with some of the first works that I made, like when I was working out the iconography of using cats as symbols and signifiers for the Black female with Panthera. It was my largest work at that time. I remember wanting to make it larger. [Panthera] was four-by-six feet, and, for me, that was extremely large. Prior to that, I was working on two-by-three feet—what I could afford, it was all about cost—and I knew I wanted the work to reach a monumental scale. I wanted people to be confronted by the texture, the material, and the electric color. I wanted them to be confronted by this ferociousness as they were entering into the landscape. That was the beginning of knowing that I can actually do more, and go bigger, and engage with or create impact for the viewer.

I think of myself as a painter’s painter, when it comes to working with formal aspects of painting. I utilize the thinking of Abstract Expressionism in terms of the all-over-ness and repetition of gestures. I think a lot about the language of painting, bringing forth some necessary tropes into the work, and using that as a mode of construct. When you see my painting The Grand Odalisque at Brooklyn Museum—what does that mean for the viewer? What does that mean for that sitter? What does that mean for young Black girls? I realized that having my paintings occupy these spaces is what I can give to the world, so that people can see themselves in these images on that scale.

Thelma: You said in a talk, My gaze is the gaze of a Black woman, unapologetically loving other Black women. So can we talk about the liberatory space of love? What does that mean to you?

Mickalene: Love is the only space I really know how to work out of. Is that cliché? Should I feel that emotion? Should I work out of that space? As I develop and as I become more mature as an artist, I recognize it is very important to claim the space of love and relationship, and celebrate it: whether it’s the love of my mother, the love of the relationships I’ve been in, my love for my relationship, the love of friendships, and the love for Black beauty. I want the world to see what I see in Black women. That’s the love behind making these paintings say, This is what you should be seeing, this is the desire, this is the love, this is the beauty, this is the intellect, this is what we [Black women] have to give to the world. Removing the Black female from stereotypes of servitude and overtly sexualized positions is about celebrating the Black women in my world, and this started with my mother.

One of the first paintings I did [of my mother] was from photographs that I took at Yale. I photographed her in her home, and I really wanted her to feel a sense of empowerment, I really wanted her to see herself in the light that I see her in and know that she’s worthy of her beauty, her strength, and her space. So I learned about the gaze through my mother’s eyes.

Thelma: The work that you did with your mother as the subject is so powerful, so moving, because it’s evident in a primary way that you understand each other as mother and daughter. The work also seemed to take a path through art history. You sort of portray her as a standard in many ways. Can you talk specifically about some of the works historically that inspire you and your work?

Mickalene: Historically, I think Olympia by Manet. When I’m looking at historical paintings, I contemplate these archetypal images all the time, because in some ways they piss me off. But to understand them is to go into the minds of artists and try to figure out the truth. So much of painting is about artifice, about what we think we know in the image, [but] that doesn’t really exist in it. In schools, they are constantly bombarding you with these iconic images centering the narrative of Black women in servitude positions. I needed to reverse the roles by empowering Black women. Images are powerful; we see ourselves in them.

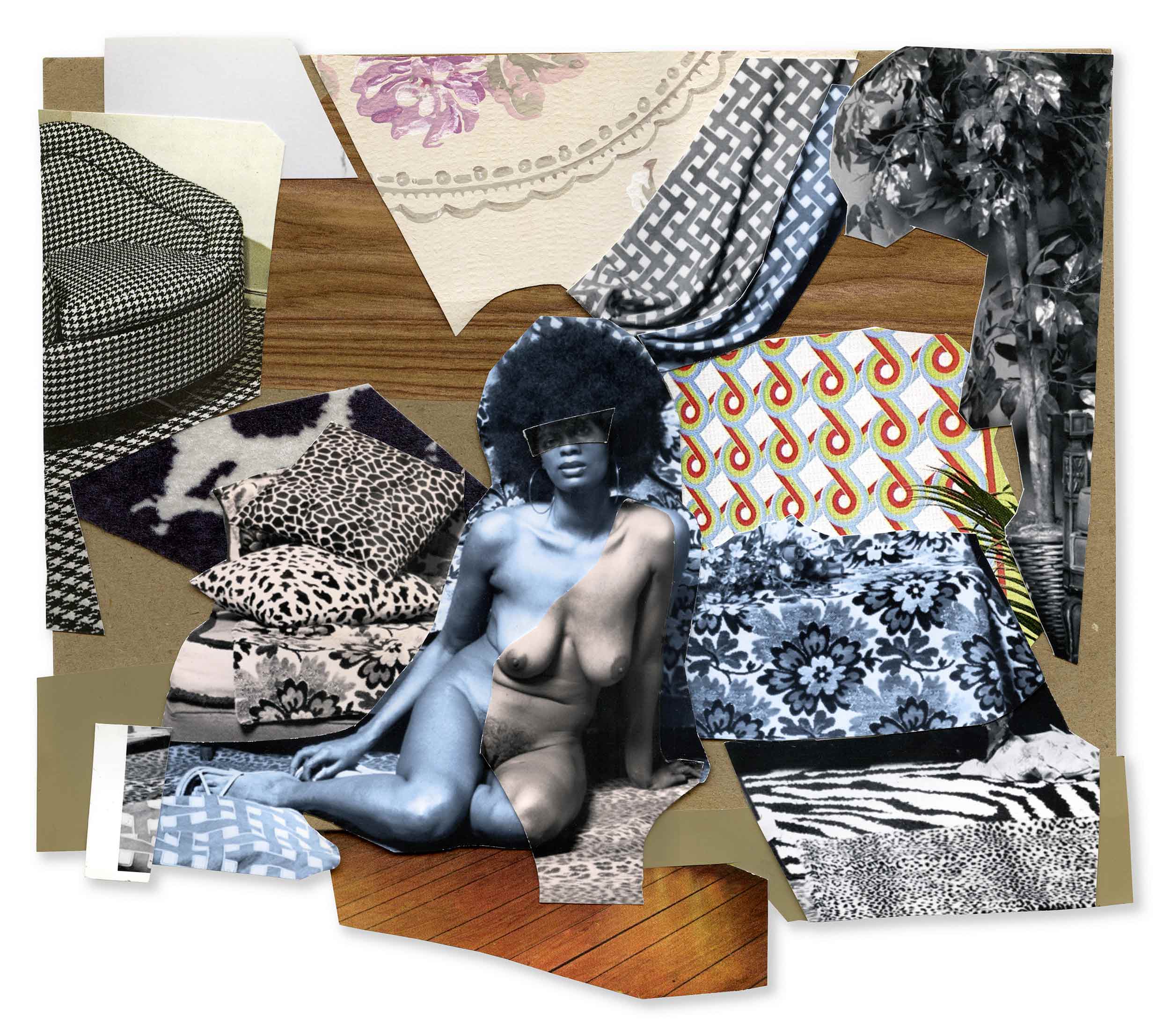

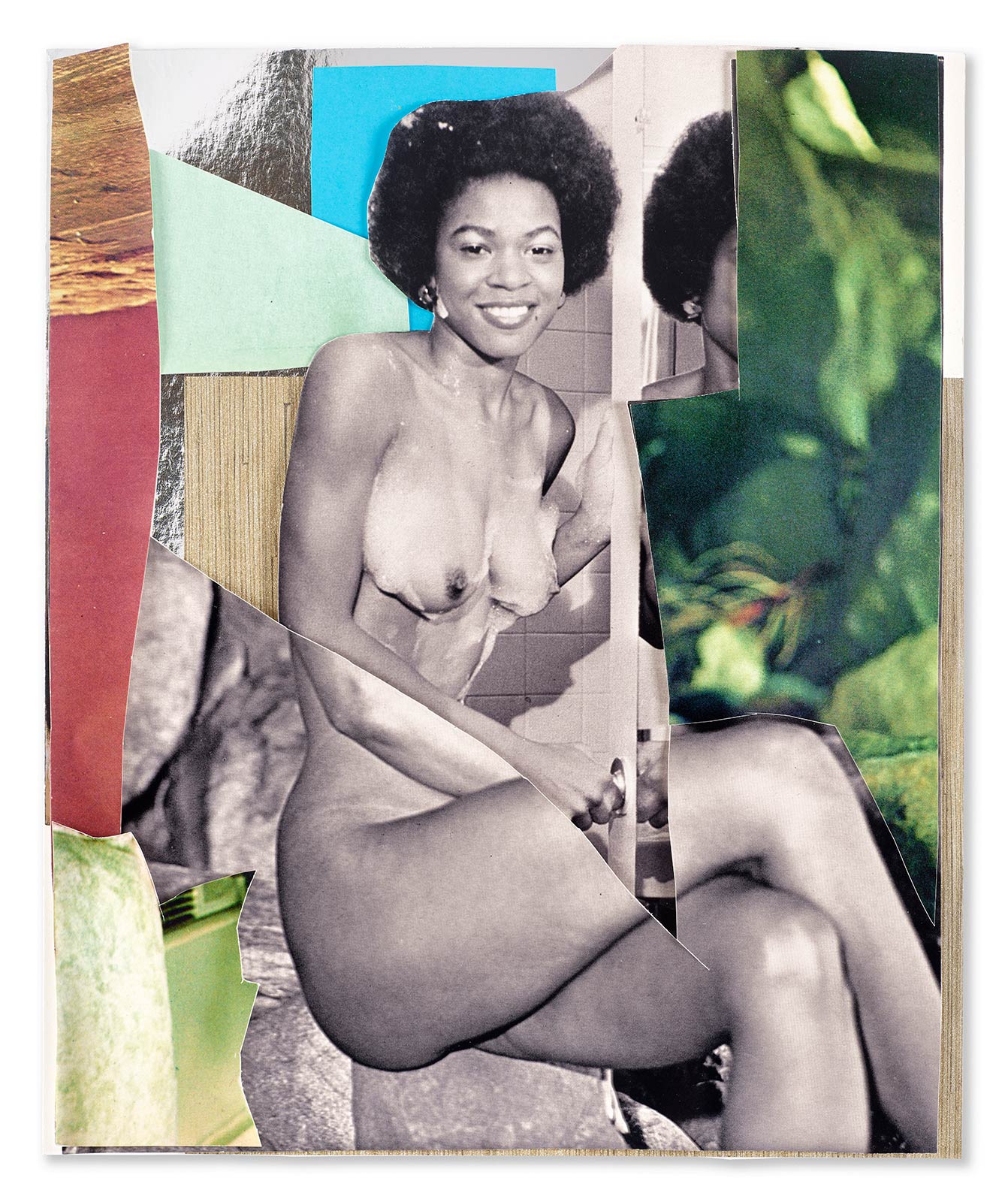

Thelma: Moving into the portfolio that will accompany this article: Can you talk about the symbolism, form, and content of this group of images?

Mickalene: This is the first body of work where I’m using archival image references. Each woman depicted is sourced from archival material that I recontextualize by deconstructing the image, reframing it in a compositionally brand-new manner. By reimagining these women outside of their original context, I hope to depict a complexity of identity, femininity, Blackness, and beauty that is outside of temporal or spatial specificity.

Since the beginning of my career, I have utilized the language of collage in many forms. These works in particular engage this part of my practice more directly, offering a rebirth or reimagining of self, of beauty, of race. The specificity of collage as a tool has allowed me to build upon a tradition of the form, while creating my own language through my mediums, drawing on multiple sources—contemporary, historical, personal, and pop cultural—in order to create complex works that present a more realistic depiction of Black femininity and beauty, questioning and confronting the continued erotization of the Black body.

Magazines, commercials, TV, and movies have historically shaped and defined what is considered ‘beautiful.’ Jet magazine was a pioneer during the ’60s and ’70s. When the civil rights of Black people were at stake, this cultural touchstone became a critical space for Black girls and Black women to find themselves represented as beautiful in popular media. The images [used in the collage work for Document’s cover] are sourced from vintage Jet pin-up calendars from 1970-1977. Most of these calendars are collected from online estate sales and collectible stores like Material Life in New Orleans, owned by Carla Williams.

Thelma: How did you first discover Jet?

Mickalene: I guess, being a product of the ’80s, most of my inspiration derived from printed matter, movies, and books. My mother subscribed to Jet magazine. She was acquisitive with her collection of Black media; she had to have Ebony, she had to have Essence, that’s how she’s sort of moved through the world. My favorite Jet section as a young girl was the Beauty of the Week, because these photos presented everyday women—housewives, college women, career women—who would describe themselves doing activities, their hobbies. As an eight-year-old, I thought, Wow, these women are beautiful, but I didn’t see these types of women in other magazines. These images empowered and validated you; they gave you a sense of adulation, a sense of pride. It was seeing those images that allowed me to appreciate my beauty, because I saw women looking like my cousins, looking like my aunties. The Jet images provided a platform for the concepts in my work by presenting and celebrating Black women as icons.

At Yale, I did a painting based on a photograph where I had inserted myself as a Beauty of the Week girl. More recently, I discovered the [Jet] calendars; many people in my world don’t know about them. They were more risqué. These images competed with Playboy and provided a space for men’s sexuality during a particular time. In the calendars, unlike in Beauty of the Week, the women are anonymous. They’re not self-described. They’re not being celebrated in the same way. I want to recontextualize their presence. By layering and deconstructing them through the language of collage, I’m reclaiming these images and having them occupy a new space in the world.

Thelma: It’s clear you were diving into the complexity of the way in which those images were created. It seems that you speak a lot about the female gaze, so where is the space of desire in relation to your definition of the female gaze?

Mickalene: Desire is always this strong feeling of longing. It’s the desire of our histories, it’s the desire of my ancestors and the other generations before me, it’s the desire of having us be seen in the same way as that idealized beauty. It’s the desire to understand your own resilience in the world. I bring forth in my work those notions of women loving women, the desire for us to see ourselves, the desire of queerness, the desire to say, ‘Yes, I’m a queer Black woman who loves other queer Black women.’ I examine my own self and question my own sense of self through my love and the desire of women, not only in relation to the historical images but also to the relationships regarding the systematic oppression of Black women that we ignore in society. When I think in those terms, I don’t necessarily want to always deal with the trauma. We all have trauma, we all have a story that derives from that trauma.

The desire is to inspire. Thinking about what my mother has endured in her physical self, being this 6’1″ woman who all her life battled with sickle cell anemia and all her life had to struggle with her health, and yet has always presented her best self, standing tall and strong and letting the world know that she exists. Seeing that desire within her to live, and to love, has instilled in me the desire to celebrate life.

Thelma: It’s a real act of resistance.

Mickalene: And rebellion.

Thelma: And recognition.

Mickalene: It’s important to understand that we’re different types of women, and we have different desires. Even just reading and thinking about Maya Angelou and what she thinks about Black women’s sexuality. Oftentimes, we are sexual selves, and I used to shy away from those notions. I think that’s when my work shifted; I thought, well, maybe my work is exploitative when I’m photographing my lovers nude and wanting to paint that, but also wanting to share and show the love between us. But really, it goes back to the sense of self, and knowing that we should love and express who we are. And we have a right to.

Thelma: This fall, you are going to have four exhibitions around the world.

Mickalene: Yes, I’m doing a global show with Lévy Gorvy, starting with New York, then London, then Paris with a two-gallery show at Natalie Obadiah, then Hong Kong. For each space, there’ll be an exploration or chapter of work that will start with my investigation of the Jet calendar images; taking those images and refragmenting and recomposing them, to allow these women to exist in the world and not just as anonymous pinups.

I’m very excited about the Paris show. For the first time, I will present a more direct and obvious body of my work, where it’s really evident that the work is more social, political. I’m working from archival images, from the ’60s to the present, concerning the Civil Rights Movement and the brutality against Black bodies—historical images that have been related to the massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma; George Floyd; Black Lives Matter; and Sandra Bland. It’s the systems that are designed to disenfranchise Black people that make it difficult for us to succeed. That’s why I don’t take for granted my accomplishments, what I have, and where I come from.

Thelma: I have to ask: Because you have been living in the world as an artist for over two decades now, can you reflect from the space we’re in right now on what role art and the vision of artists can have in a world that continually needs change?

Mickalene: I think the role of art is crucial. I think art disrupts, it erupts, it ignites, it creates change, it transforms lives. The role of an artist is to start from an authentic place of truth and to work from that place; really observe, use the world around you as inspiration and [a set of] tools to take back to your studio, and then articulate it through a creative process. The journey is not going to be easy. But have faith that what you’re doing is what you should be doing. Persevere.