In the 100th year of Chanel’s iconic No.5 perfume, Document travels to Grasse to discovers the generational roots of the flower fields that fill each bottle

On an evening in Grasse, France in late summer, as the day’s heat is swallowed into the flower fields that crown the region the perfume capital of the world, there is a silent symphony of jasmine buds that begin to bloom, humming their soft, narcotic fragrance into the night air. At dawn, the harvesters arrive, the silence shifts with the soft flurry of movement and the faint, rhythmic click click click of the flowers being popped from their plants; each handful exhaling more perfume, before being carefully placed in baskets under a humid cloth so they don’t expire in the sun.

“The scents are the language of the seasons,” explains Joseph Mul, standing in the middle of his thirty-hectare field as his team of 60 harvesters quietly pick through the bushes behind him. “The rose announces the spring. Jasmine means fall is coming.”

The farm has been part of the Mul family estate for five generations, growing centifolia rose, geranium, iris, tuberose, and, of course, jasmine (a signature note in Chanel No.5 since Ernest Beaux created the fragrance in 1921, using flowers from this region in the South of France). Mul partnered with Chanel in 1987 to cultivate flowers exclusively for Chanel fragrances. While he is now approaching retirement, and will eventually hand the reins over to his son-in-law Fabrice, he remains visibly enchanted by the raw material, a twinkle in his eye as he explains the art of hand-plucking jasmine—the click as the flower leaves the calyx is a good sign—and its change in scent from sweet to sharp in a moment within a closed palm, the green tea notes a signature of the jasmine grown in the Grasse region. “My favorite time of harvest is the first day,” explains Mul. “On that first day, we are really taken by the scent.”

The art of perfumery in Grasse, a town on the French Riviera in the hills north of Cannes, earned UNESCO World Heritage status in 2018. But its fields and, in turn, the practice of perfumery, were at once at risk of disappearing. In the ’80s, as the hitherto agricultural region became more tourist-centric, flower fields started to be sold to those seeking secondary and holiday homes as farming families decamped to the cities. Soon, Grasse became at risk of losing its agricultural integrity. While the Mul family had been cultivating perfume plants since 1840, the Chanel partnership in 1987 bolstered the operation. Growing and supplying flowers for the brand’s fragrances helped maintain disappearing flower crops and ensured the availability of jasmine, tuberose, and other flower harvests each year (it is said that 1,000 jasmine flowers from the farm go into each bottle of Chanel No.5).

“The scents are the language of the seasons, the rose announces the spring. Jasmine means fall is coming.”

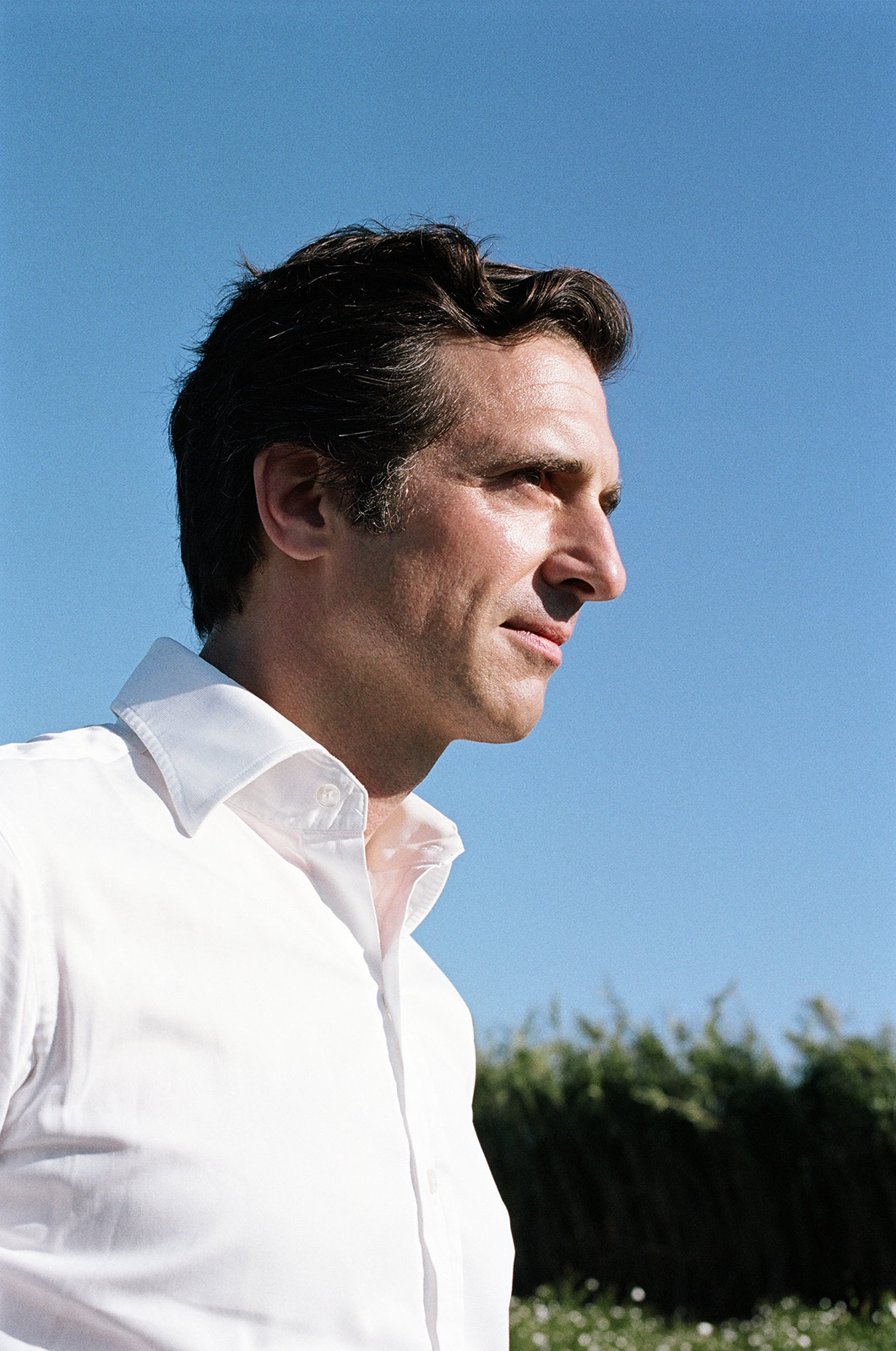

As the day wears on, Olivier Polge, the nose and master perfumer of Chanel, arrives in the fields, greeting Mul with la bise, the French tradition of a kiss on each cheek. Fragrance-making has long been a family affair for Polge, who was not only born in Grasse, but whose professional predecessor, the fourth nose in the history of the house, was his father. Jacques Polge, during his 37-year tenure, created some of Chanel’s most beloved fragrances including Coco, Coco Mademoiselle, Allure, and Chance. At Chanel, the younger Polge has already realized fifteen fragrances that encapsulate the complexity that so often lies behind simplicity, and the tension between freedom and constraint, the markers of Chanel’s style philosophy. Misia, Polge’s first fragrance for the house, was inspired by Misia Sert, a close friend of Coco Chanel. Then came Gabrielle Chanel in a score of white flowers. When it came to reinterpreting the house’s iconic No.5 fragrance, Polge translated its opulent depths into the lighter, fresher, more youthful No.5 L’Eau. Polge also created a repertoire of ‘Les Eaux de Chanel’ named for the house’s emblematic locations (PARIS-BIARRITZ, PARIS-VENISE, PARIS-DEAUVILLE, PARIS-RIVIERA).

Although Polge was raised in Paris, his first scent memories are linked to his childhood holidays, spent at his grandparents’ home in the South of France, where the warm Mediterranean air carried the scents of summer herbs like thyme, lavender, and cistus. As a teen, his first instincts were to play to his other senses, enjoying the tactility of working with leather and paper at a bookbinder before studying art history and music. Having discovered piano as a teen, Polge stills plays daily.

“Jasmine is a major chord,” offers Polge when asked what the jasmine note evokes. “Cheerful, perhaps optimistic. It is a scent that, like tuberose, gives a sense of strength that suits personalities that are empowered and extroverted. It is a scent that is extremely engaging and very feminine and can be used in its different phases in different ways,” he offers. “It can be used in its freshness, especially when joined with orange blossom. But there’s a ‘heated’ part of jasmine that is more animalistic, stronger and very woody.”

When Polge joined Chanel, besides having his own family ties to the brand, he was intrigued by the way the house, an international company, worked hand-in-hand with Mul’s local, family-run business. “What I found wonderful, in working with the family, is that the agricultural aspect is fantastic. This counterpart is a fantastic compliment, a beautiful contrast to the luxury image of Chanel,” Polge offers. “We appreciate it more and more over time and it’s really an essential part of us.”

Soon, Polge will break for lunch, sitting down with Mul and his family. As Polge has his photo taken in the fields, Mul gently drops a plump pile of jasmine flowers into my hand, instructing me to put them in my coat pocket.

After lunch, the pickers begin to return from the fields to weigh their harvests for the day with Mul and his son-in-law, Fabrice. Within minutes of weighing, the flowers are loaded into an on-site extractor, where the hundreds of molecules making up the scent of the flower are distilled. Here, 350kg of jasmine will create 1kgs of concrete (a semi-solid mass made from solvent extraction of the flowers) which yields 500g of absolute. It is this absolute that finds its way into a bottle of No.5.

A little after 1pm, the summer heat is too great to continue, bringing a risk of wilting the flowers, and the harvest is done for the day. Later, Muls tells me, the fragrance will follow the harvesters as they make their way home, their clothes soaked in the perfumed dew that dotted the jasmine they picked early that morning. The fields wind down back to silence, and soon the evening’s floral symphony begins again.