DeForrest Brown, Jr. takes us inside the countercultural publication that served as a relic of desire and community-building before the internet

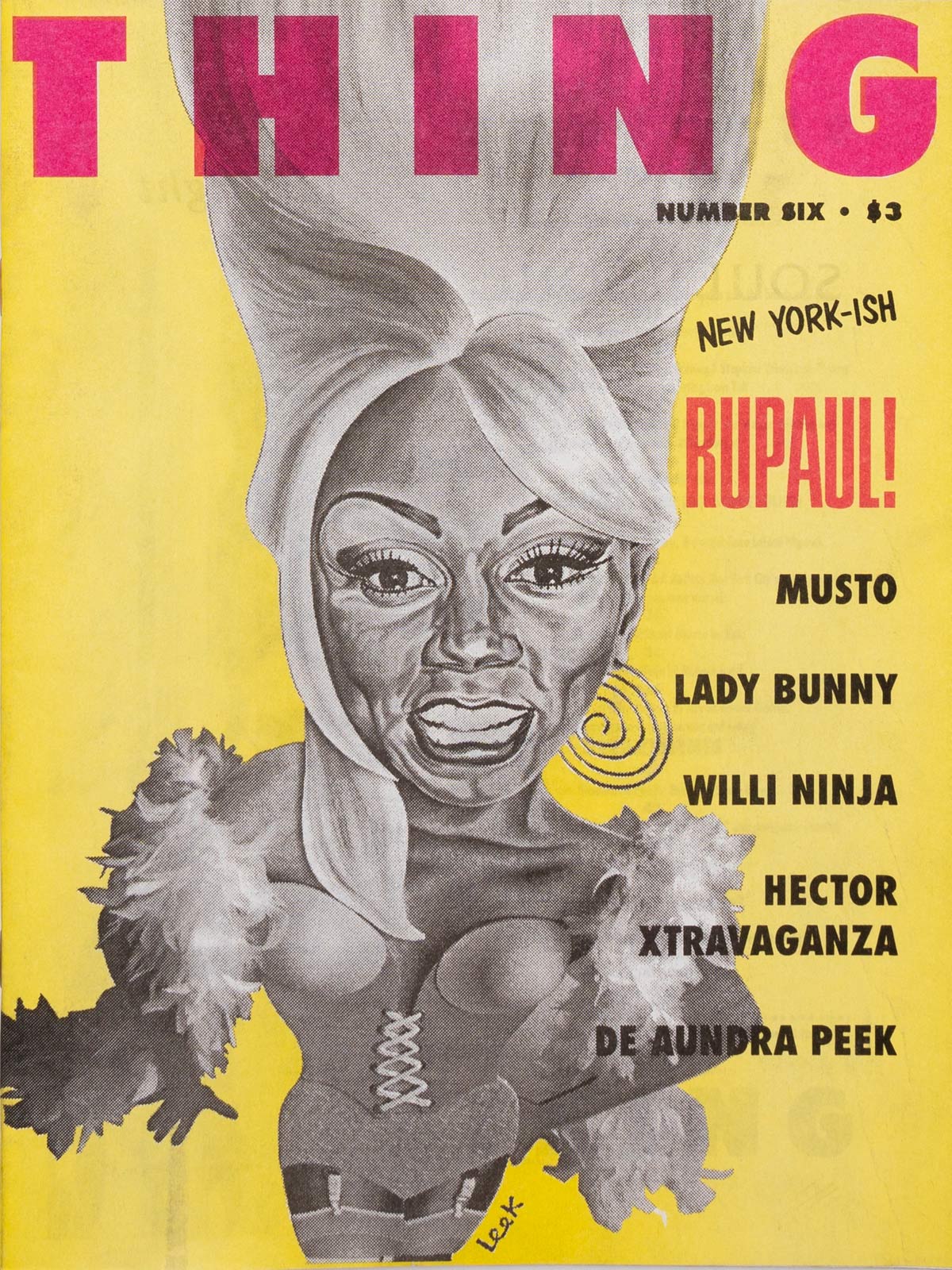

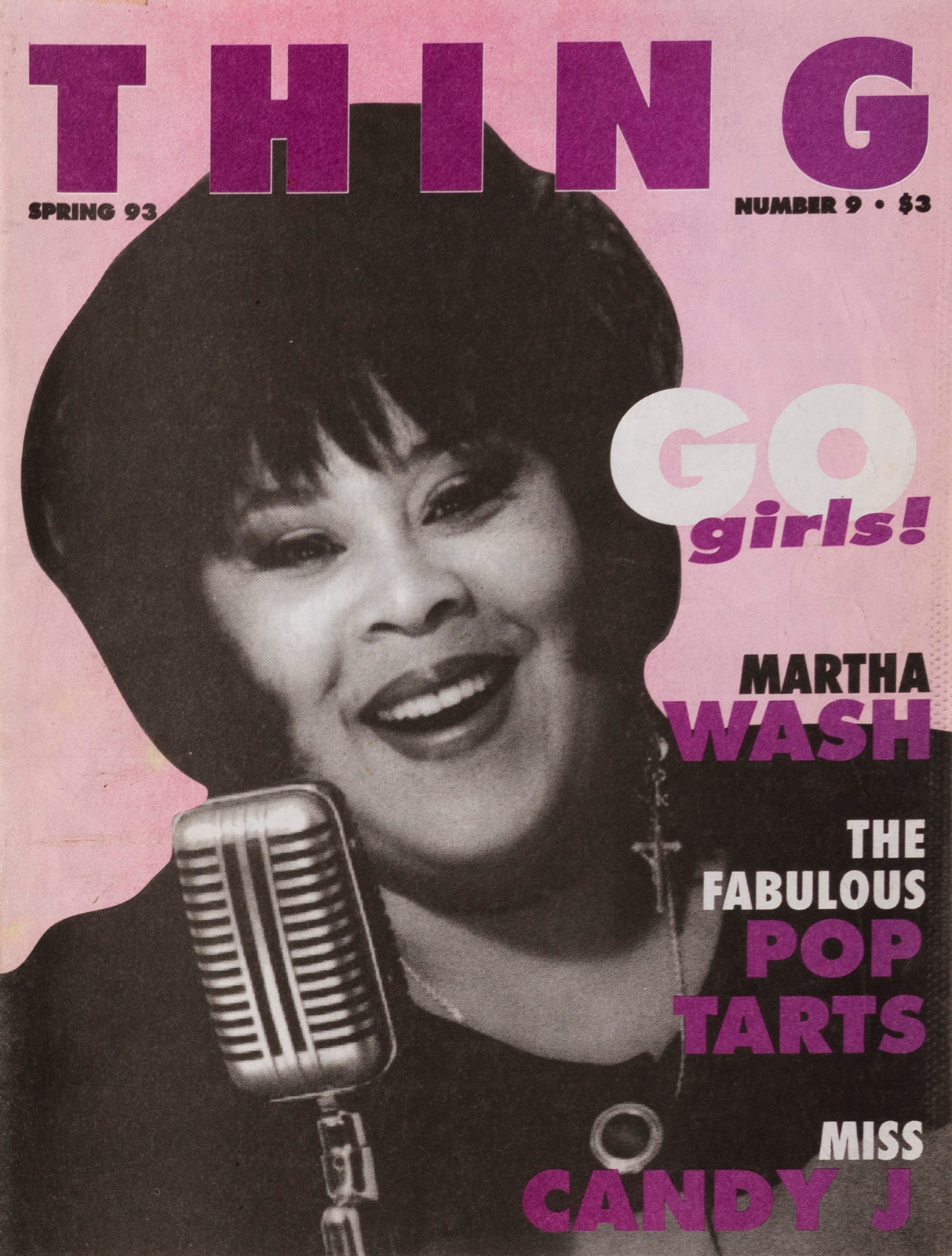

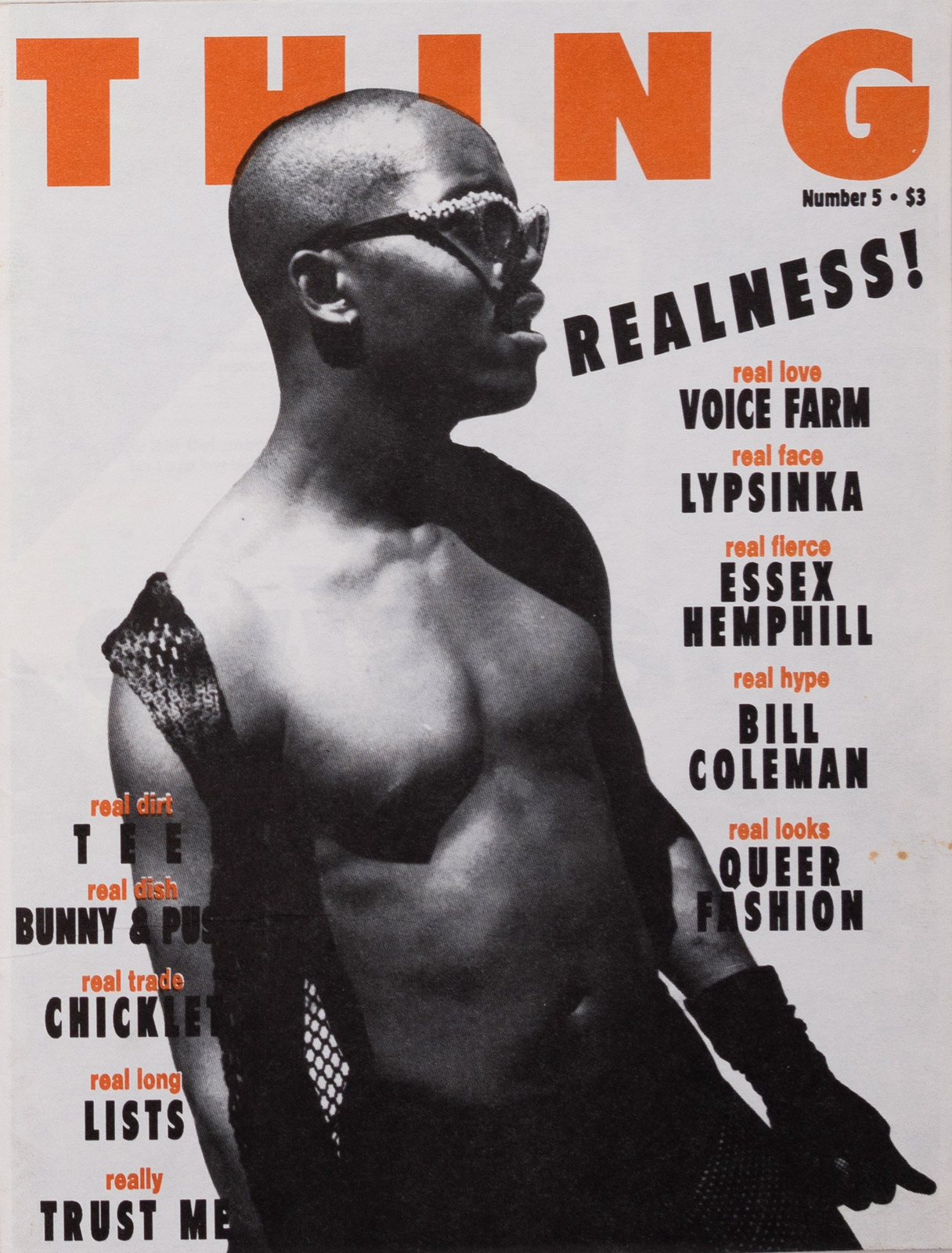

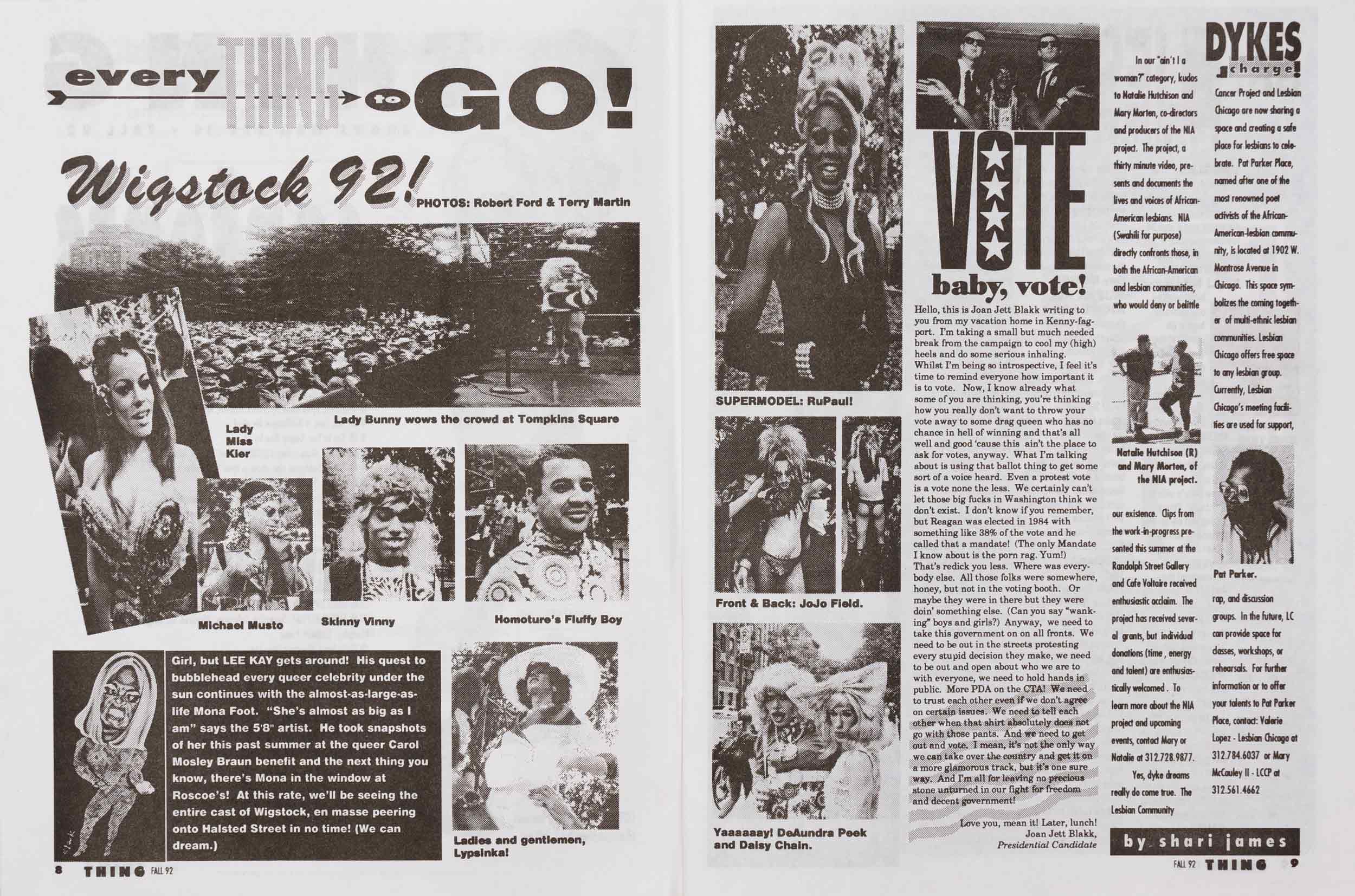

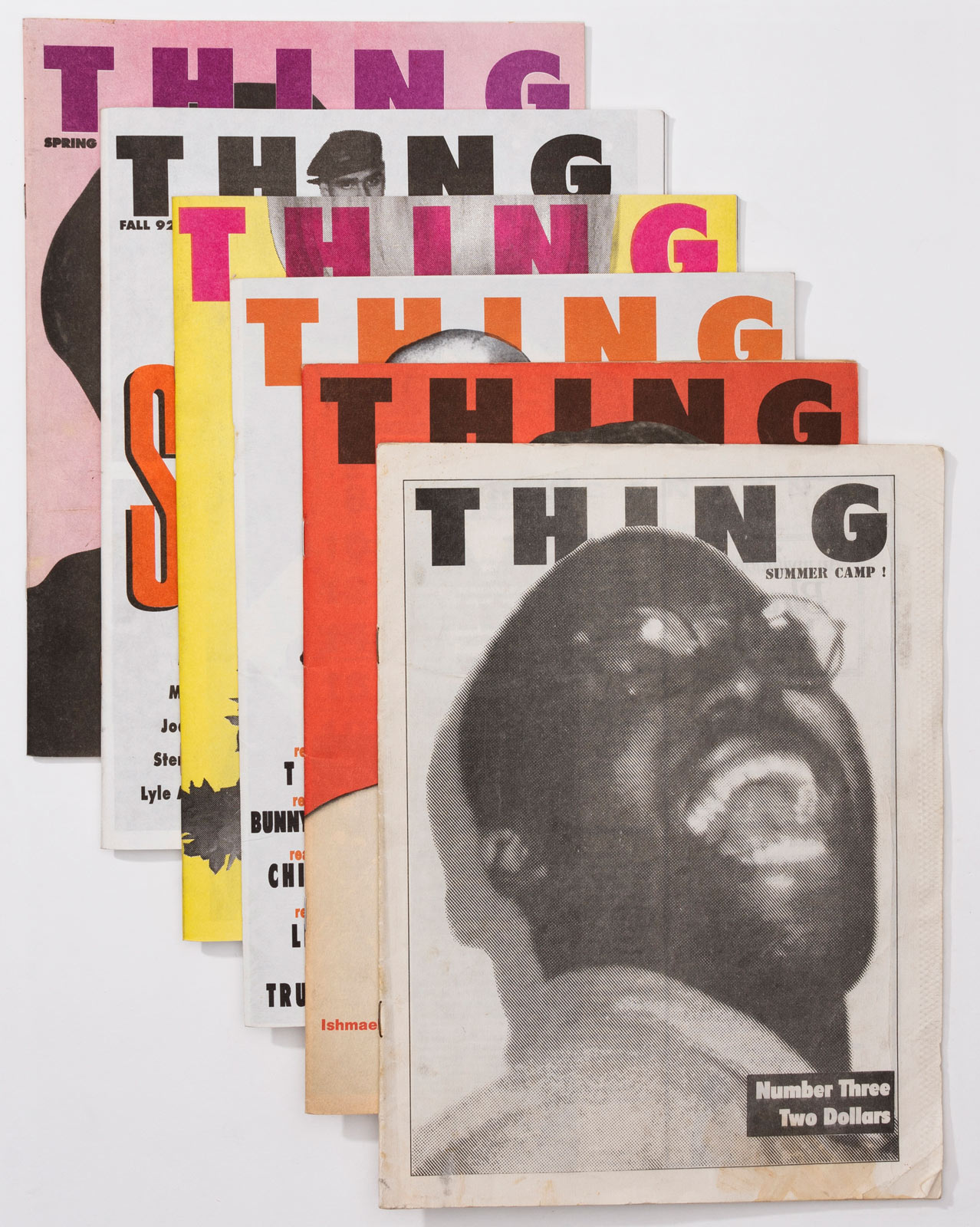

“She Knows Who She Is,” read the tagline of the first issue of THING magazine. It was November 1989, two months after ACT UP movement members had chained themselves inside the New York Stock Exchange to protest the inflated pricing of the AIDS medication, AZT, when writer and DJ Robert T. Ford—alongside Trent Adkins and Lawrence Warren— published the inaugural edition. Featuring quippy columns, editorial features, and fiction, the aim of THING was simple yet revolutionary: to document LGBTQ+ and nightlife culture in Chicago.

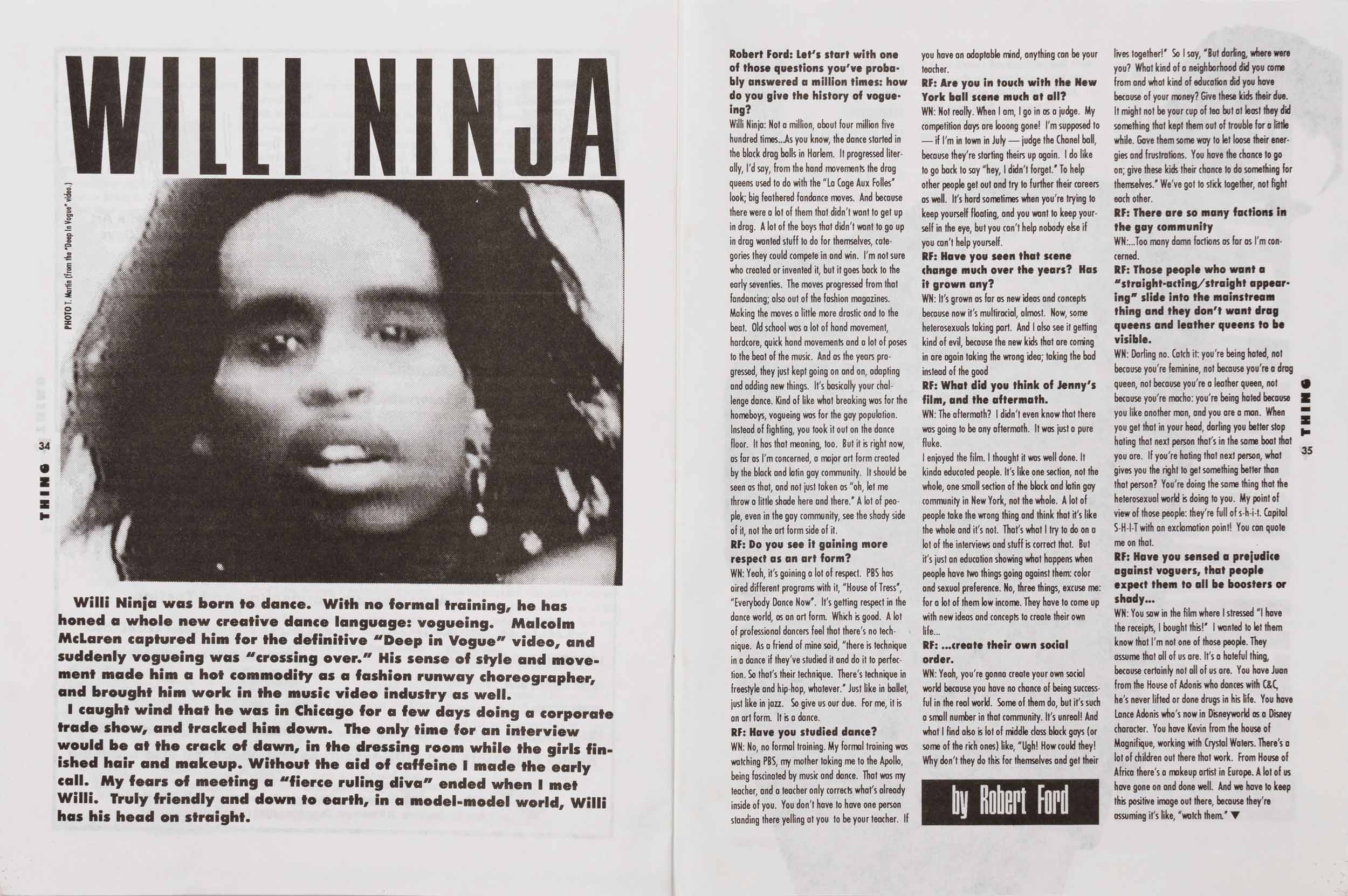

Two years earlier, Ford had aspired to embrace an emergent intersectional counterculture with his 1987 magazine project Think Ink as the turbulent second half of the 20th century accelerated from the Black Power and Black Arts Movements, producing a broader chosen community bonded by the excesses of an integrationist post-soul aesthetic. Developed at the end of a second Great Migration of African Americans from Southeastern rural states to Northern industrial cities like Chicago—and the accompanying “white flight” to the suburbs—Think Ink and THING were a means of establishing roots for African Americans living in these newly individualist urban environments that offered more access to creative culture. Common terminology and cultural slang would be defined and contextualized in both Think Ink and THING by Trent Adkins, in a column called the “Tee Glossary,” which archived the language of Chicago nightlife in conjunction with need-to-know countercultural figures in music, fashion, and art.

“So, just to set the record ‘straight,’ it was from the cradle of the Black urban gay experience that house music was born.”

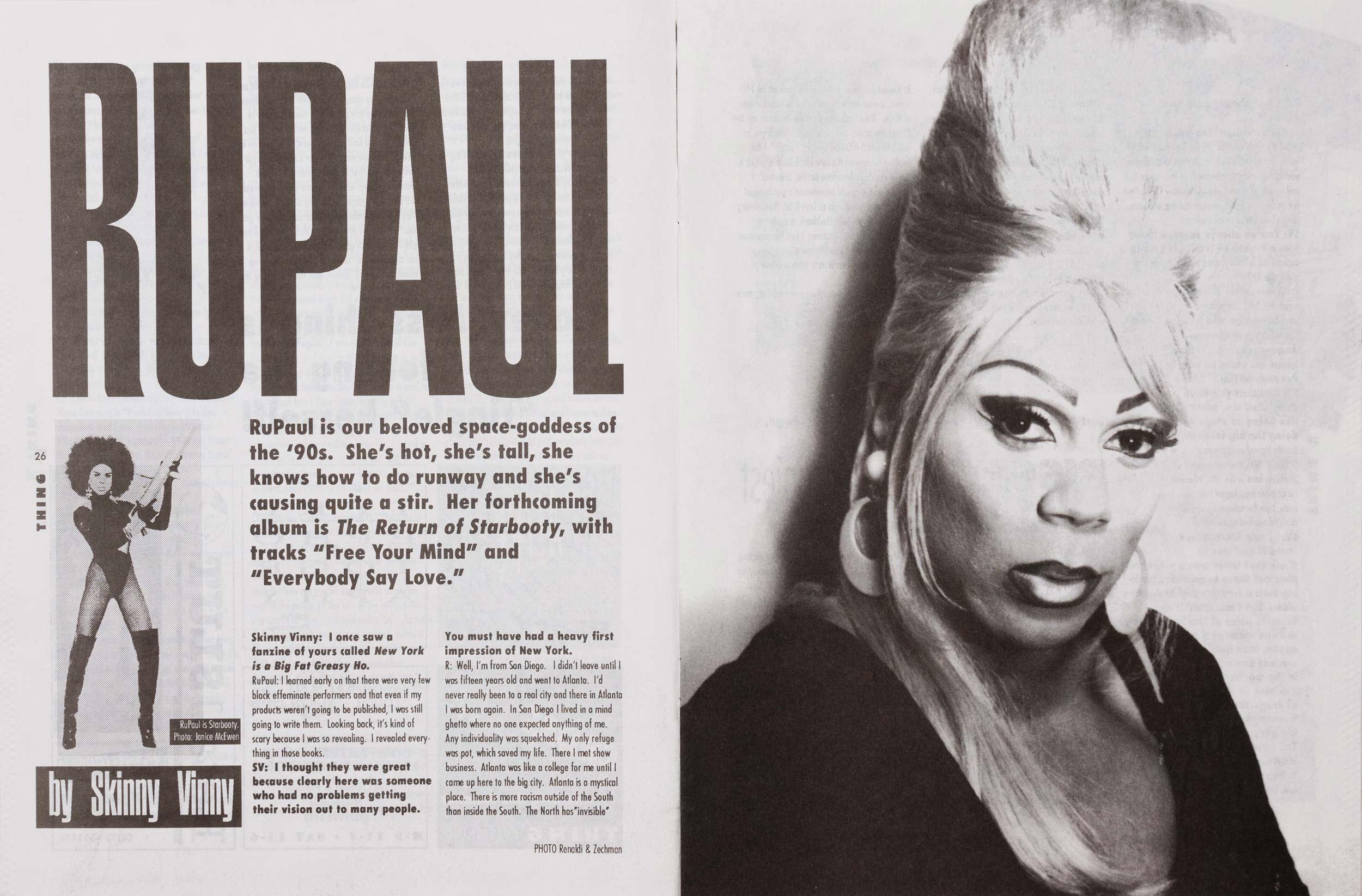

Throughout Think Ink’s run, Ford drew from his job at Rose Records, featuring artists from the house music scene with “best of” lists, reviews, and a music column edited by Andre Halmon called “Real Estate.” THING’s second issue, Whose House Is It Anyway? surveyed the rise of house music from queer underground Chicago and New York club spaces and led with a cover image of Little Richard, alluding to the singer as being an early Black, queer music industry icon.

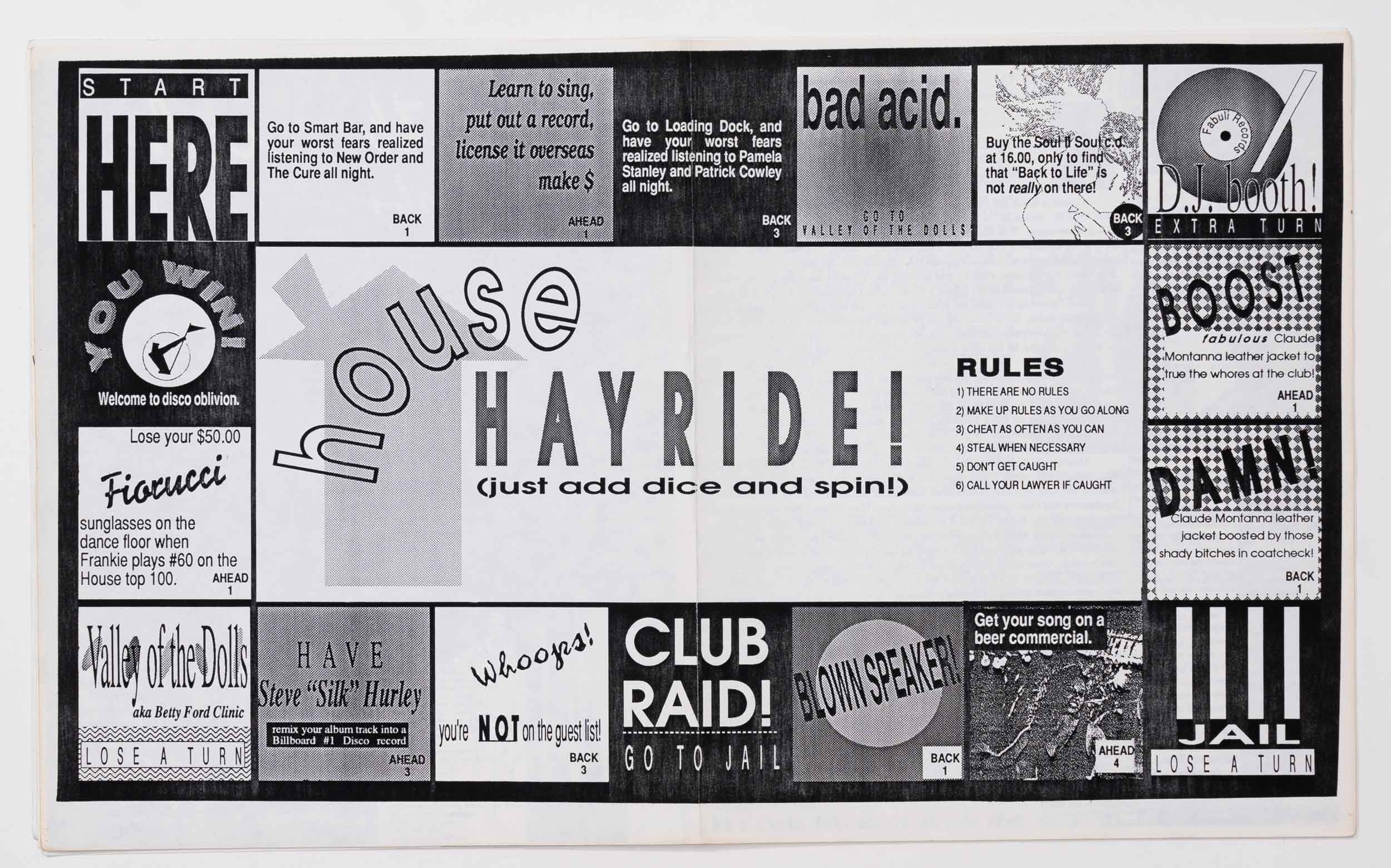

In his article, “Acid Soup,” Chris Nazuka, of the acid house trio Symbols and Instruments, reminisced about his first time tripping on LSD while dancing at Muzic Box, noting, “This music is only about the intoxication, the trip is the destination.” In another article, THING interviewed the deep house DJ Riley Evans about the Chicago nightlife scene and his complex infusion of gospel and classical music tropes into house. “Music shouldn’t just be the same thing over and over and not really say much of anything; it should take the person somewhere,” Evans declared, recounting his personal fascination with longform songs like “Love in C Minor” by Cerrone, a 15-minute disco suite with a salacious voiceover intro depicting a group of friends making eyes with a man across a bar. As many dance musicians and friends of Evans fell victim to the AIDS epidemic, he described feeling a heightened sense of community amongst all of the loss. Terry Martin, a frequent contributor to THING, started Crossfade, a music magazine at the intersection between music and gay culture, in 1992, and asked Ford to co-publish it. “Long before it was labeled, house music began to evolve to meet the demands being made on dance floors in Chicago,” Martin wrote about “Chicago’s House History” in Crossfade’s November issue. “So, just to set the record ‘straight,’ it was from the cradle of the Black urban gay experience that house music was born.”

“THING assumed a position in everyday queer life in the late ’80s and early ’90s that was tucked away from the societal standards of the mainstream, fastidiously heterosexual America of the Reagan/Bush years.”

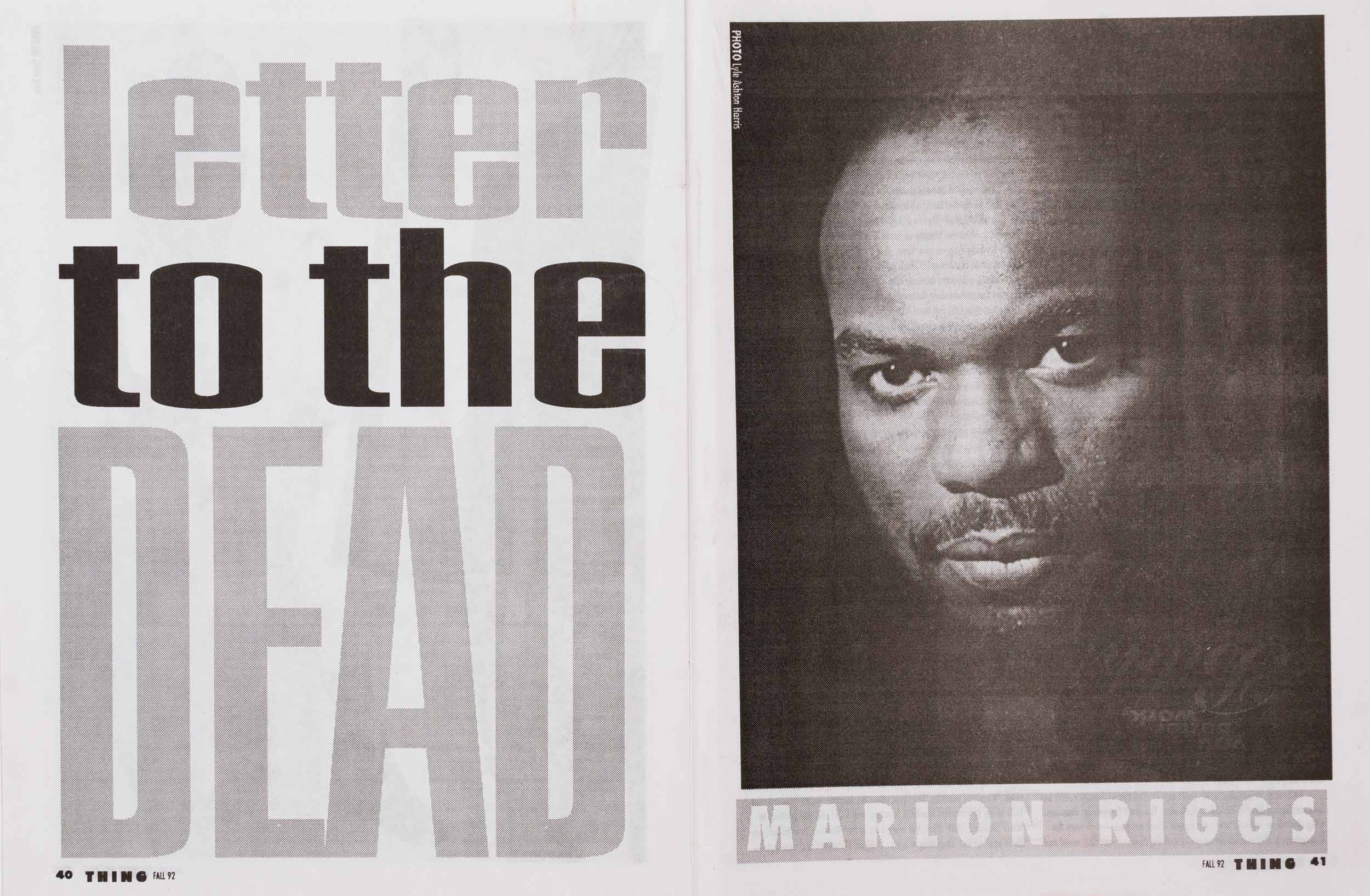

From November 1989 to August 1993, THING published 10 issues. In 1994, at the age of 32, Ford died from complications related to HIV/AIDS, having documented his declining health in a series of personal essays published by PLUS magazine called “Life During Wartime.” He wrote, “Escapism is fine on occasion, but investing an equal amount of energy into facing this thing and lending your support is what will ultimately make the difference. Call your friends who are positive to say hello…. If you are positive and keeping it to yourself, tell somebody who cares about you, and notice how the sun rises the next morning….”

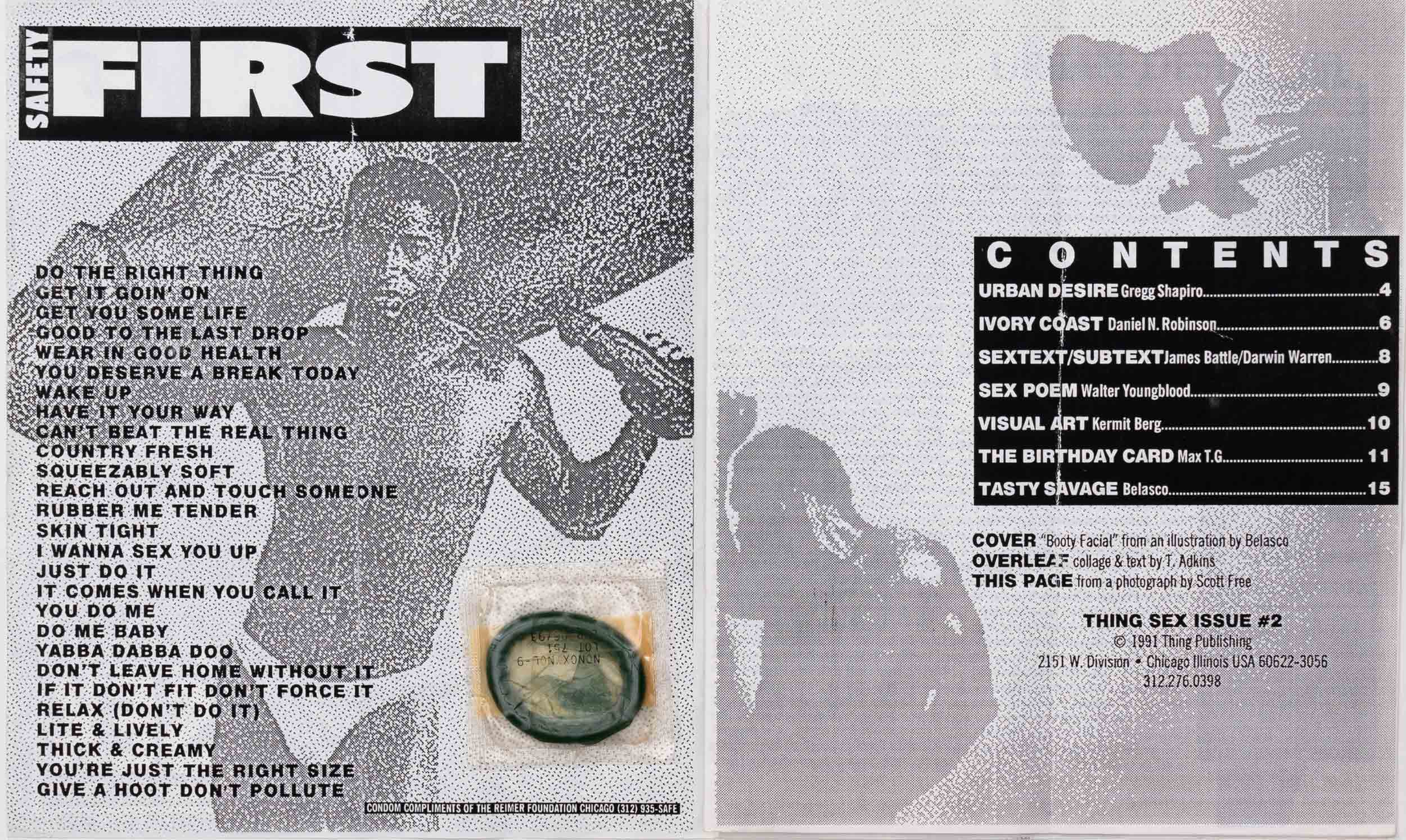

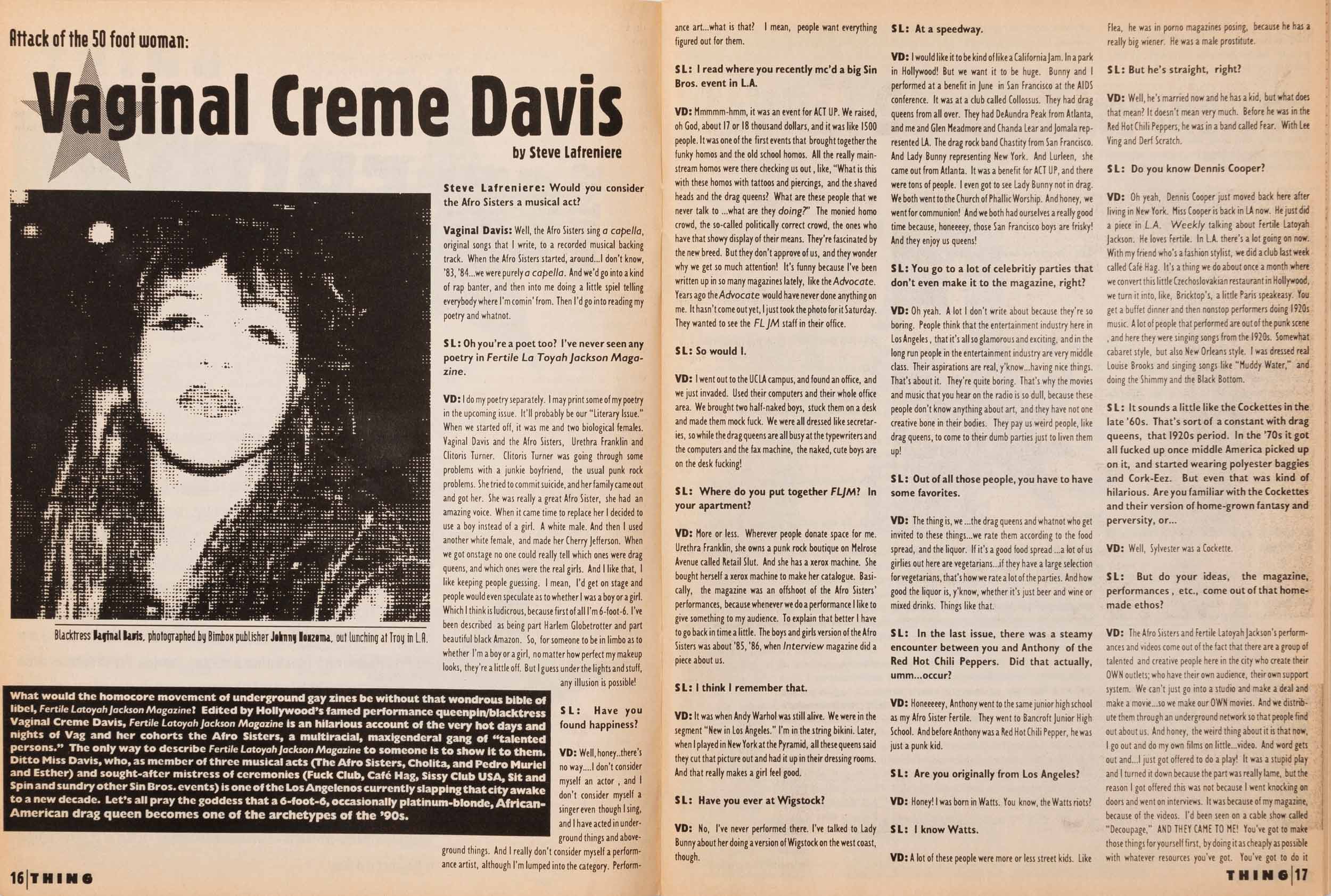

In Cruising Utopia (2009), Queer theorist José Estaban Muñoz wrote of the liminal spaces of pleasure that could be found in off-the-grid queer zones such as nightclubs, asserting that such spaces offered “a certain transformative possibility” that functions as a “performance of queer utopian memory.” Similarly, THING assumed a position in everyday queer life in the late ’80s and early ’90s that was tucked away from the societal standards of the mainstream, fastidiously heterosexual America of the Reagan/Bush years. It is a relic of the desire and countercultural community-building that existed prior to the instant gratification and collapsable spaces of the internet. “I can’t help but hope at least one person understands and attempts to give another what has been given to me and others by such a small group of individuals,” a contributor wrote in an article titled “Homeless in Chicago.” “I also want other gay, homeless, young, Black men to know there is help available in the city of Chicago.” One of the magazine’s Sex issues would come with a condom taped inside its cover; another displayed a warning and a reimagining of societal standards, reading: “In the real world, people have sex. Some with members of their own sex, others with members of the opposite. Some with both. So, what’s the big deal? Isn’t art supposed to be about life?”