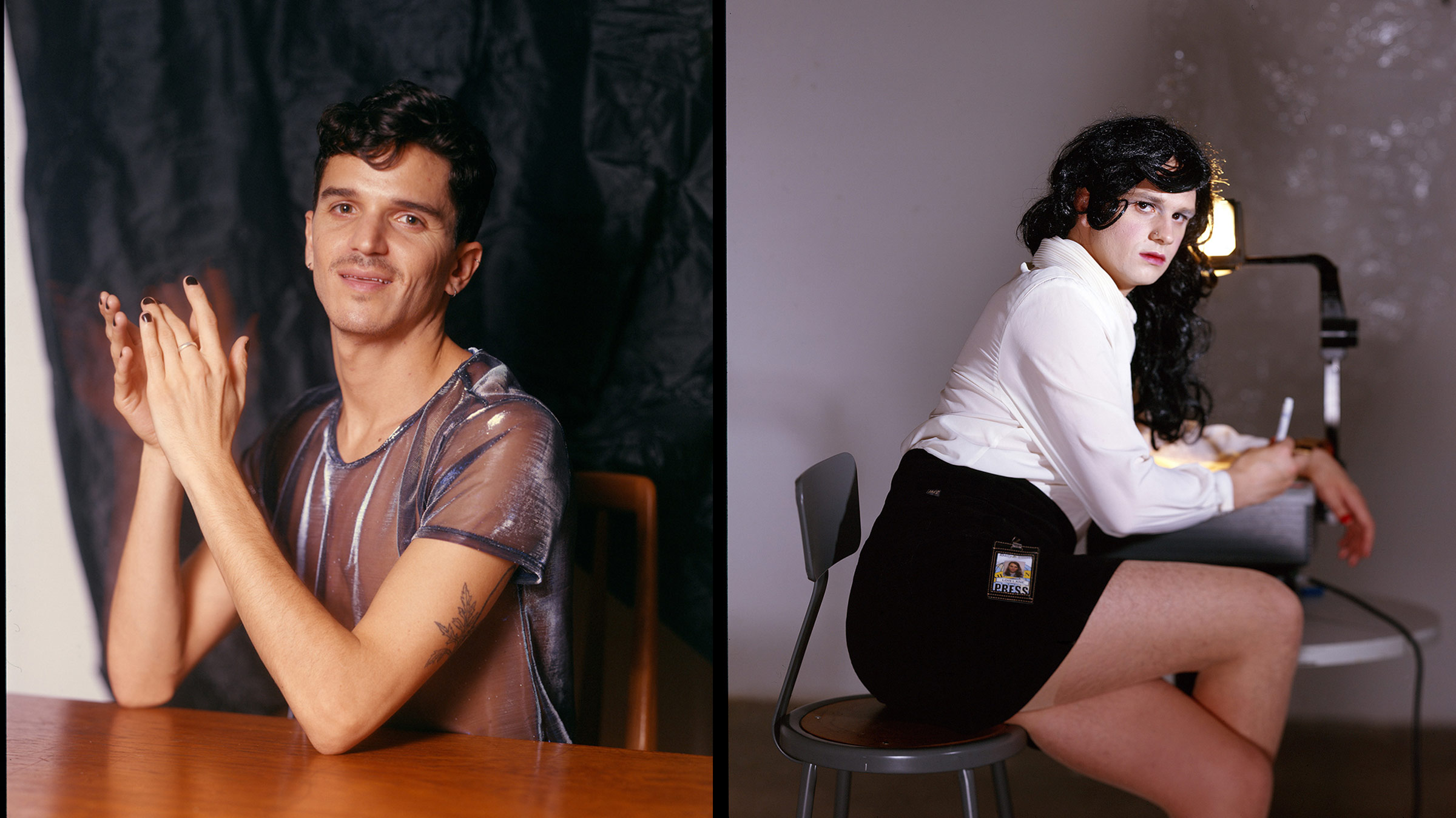

In his first published monograph, 'The Ice Palace is Gone,' Lewandowski captures intimate portraits of queer communities and interiors

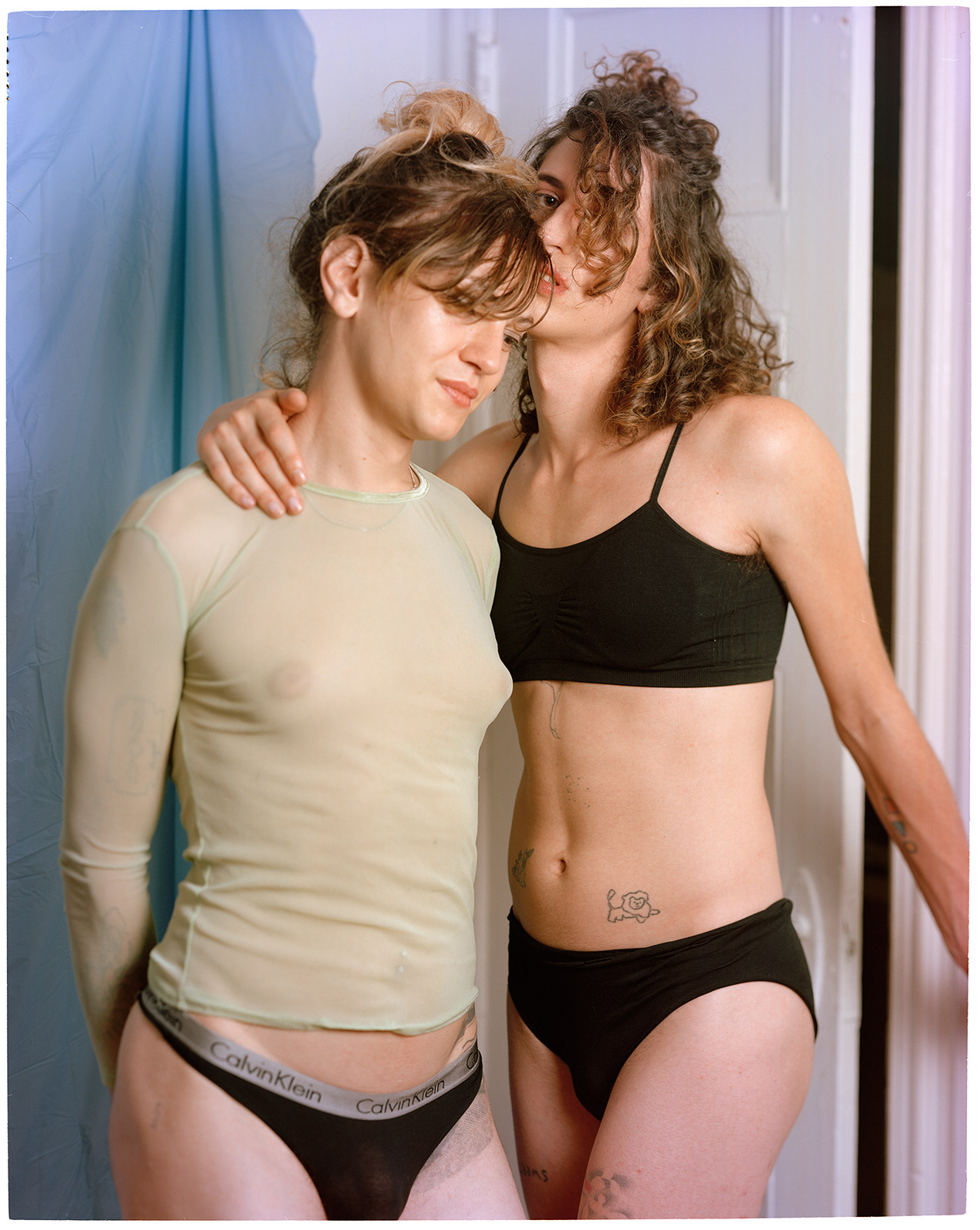

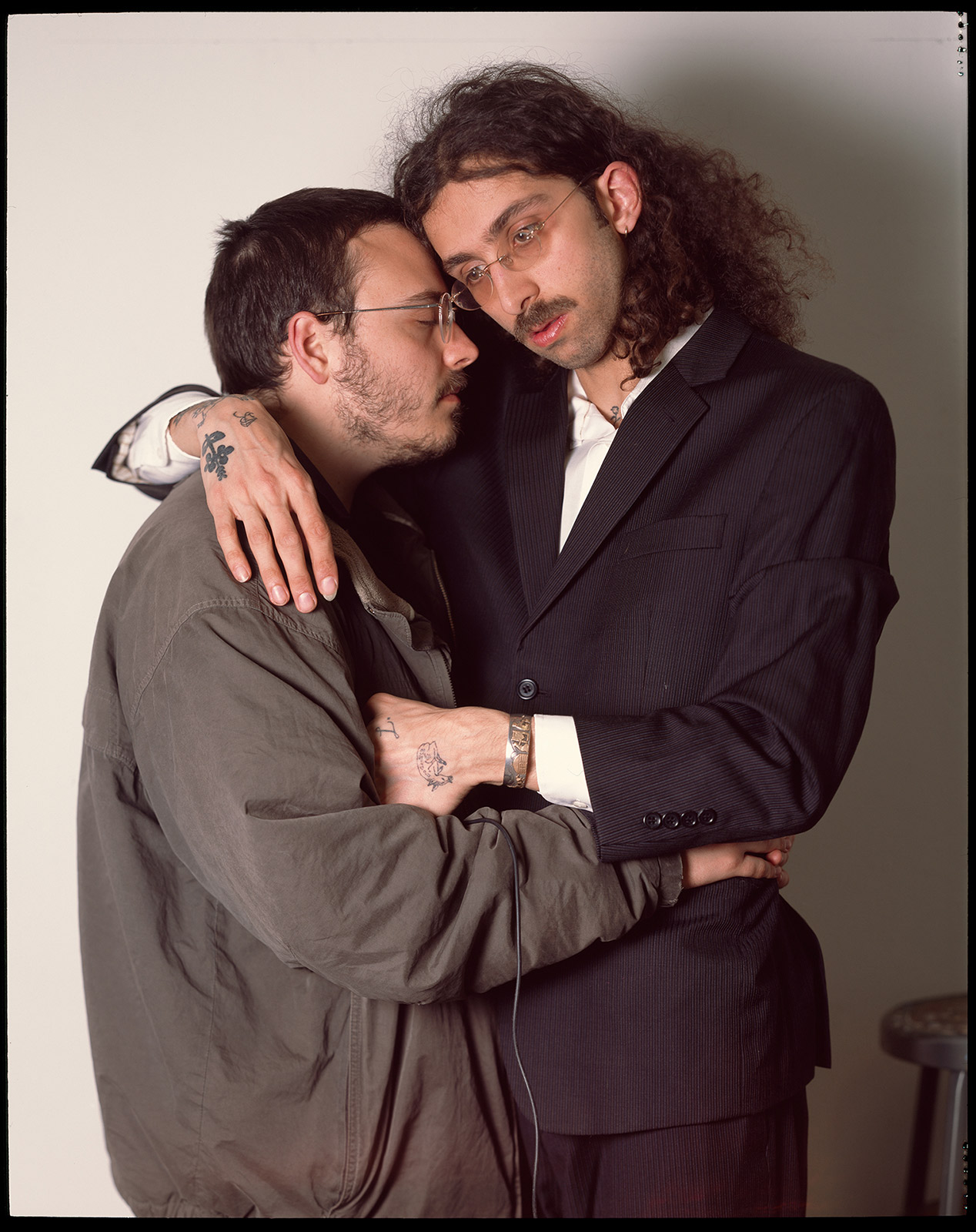

Ian Lewandowski’s first monograph, The Ice Palace is Gone, published by Magic Hour Press, is a collection of large format color photographs depicting queer identities and interiors within the context of community and care. Alluding to the nightclub on Fire Island, the Ice Palace is a space that represents the temporal and precarious nature of queer spaces, and the necessity for them to be constantly rebuilt and reimagined. In The Ice Palace is Gone, Lewandowski creates honest depictions of those he photographs, while presenting a potentiality for who they could be. Lewandowski’s portraits crystalize his subjects as characters within this seductive and surreal world, blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction.

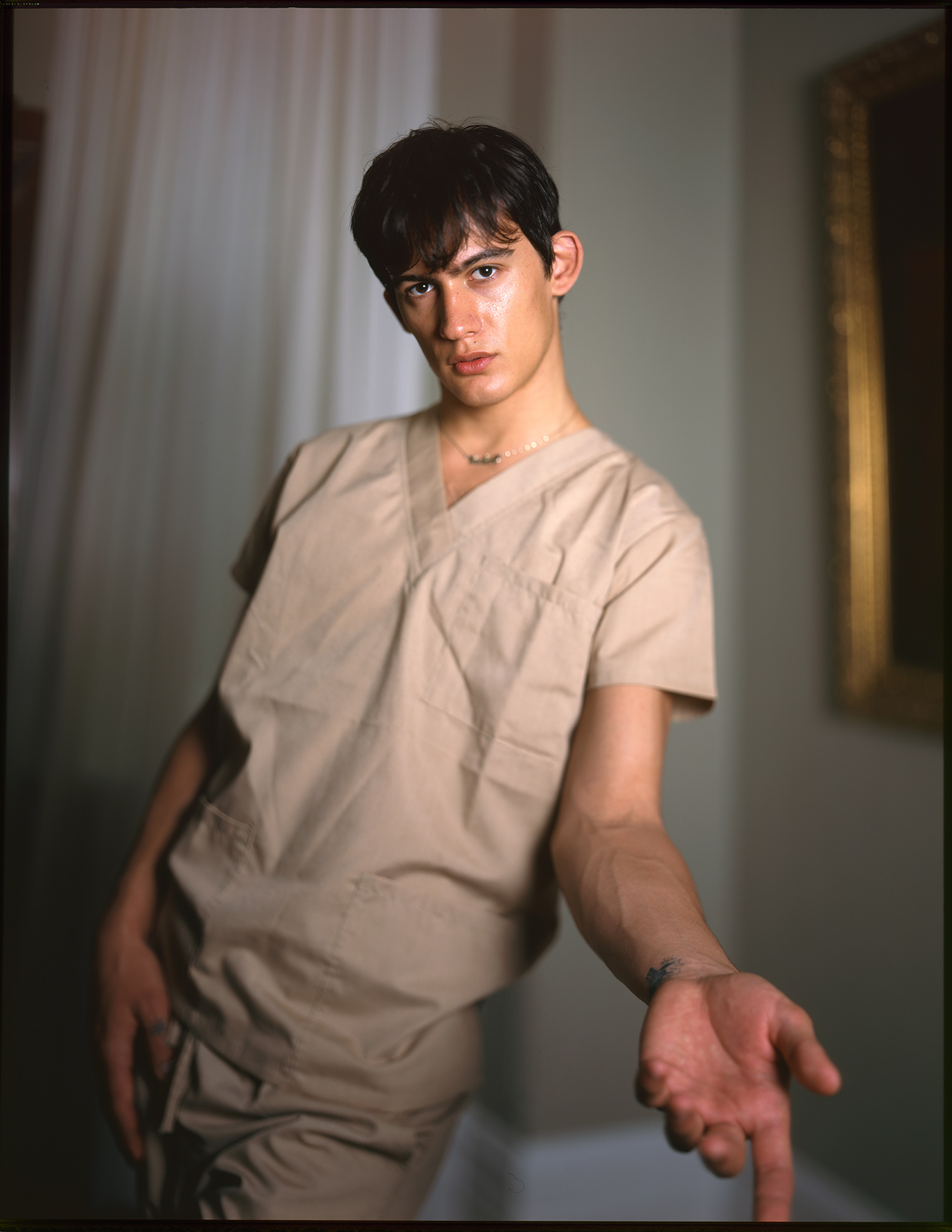

Olivia Noss: I really love the opening image of your book where a person in light brown scrubs stands in what appears to be a bedroom, offering a languid hand in invitation to this world you’ve created. I know you were being treated in the hospital for a while, which became an entry point for your work in regards to queerness and care. I want to know about your relationship with the nurses in that space. Did the ones in your book care for you personally, or were they people that you sought out?

Ian Lewandowski: I went through chemo and radiation between 2015 and 2016. I started making [The Ice Palace is Gone] at the very end of 2017, which was a time of recovery from the treatment itself—because it changes every single thing in you, really. I wasn’t making the work while I was being treated, but when I look [back], I realize it was very much informed by that period of my life.

My mom is a nurse, and has been for 41 years. [Because of this], we never went to the doctor growing up and I never learned the social cues of being a patient. I realized I didn’t have any context for how to exist in a [medical setting.] I was going through treatment, and I had to learn how to trust someone with my life. I was so interested in the people that cared for me, and what their lives were like, and I knew that it was obviously not appropriate for me to break that boundary.

I was thinking a lot about this country’s answer to healthcare, and how fraught that is. The nurses in the pictures are friends of mine who work in the healthcare industry. I was so interested in [scrubs as a] garment and what they mean. Their colors each mean different things. It reminded me of how a lot of gay signifiers are color coded.

Olivia: It’s interesting growing up with a mother as a nurse. There’s this duality, where you know her as a person before her profession. Perhaps you apply that same reversal with the nurses you meet.

Ian: Yeah. My mom would wear scrubs all the time when I was growing up. I think I always had this type of relationship to a working class wardrobe or uniform.

Olivia: Wayne Costenbaum’s quote at the beginning of the book refers to someone’s double: “My level or organization is superb today. My double and I sat on a park bench. When I called him “superb” he seconded the compliment: “I am superb.”” Could you speak about why you chose it?

Ian: I’m always either listening to music or reading something that’s making its way into my images, even if it’s subtextual. Wayne Costenbaum is a writer, poet, and essayist. I really love his writing, and how flowery it is at times. It’s so surface level, but it’s so potent as well. And with my pictures, I’m interested in surface. I’m okay with things being fake, or being rehearsed, or overly theatrical.

There are a few pictures of people in the book on New York City park benches, and recently I realized that I was looking at a lot of Diane Arbus’ work [at the time]. She took a lot of pictures of people on the benches in Washington Square Park, and I was taking some of my own. I realized, they’re all memorials. They’re all dedicated to people. [I wanted this quote at] the beginning of the book, near the dedication of it. I wanted those words to color the book—that kind of theatrical approach to words.

Olivia: There’s also an element of flattery. Addressing oneself as superb.

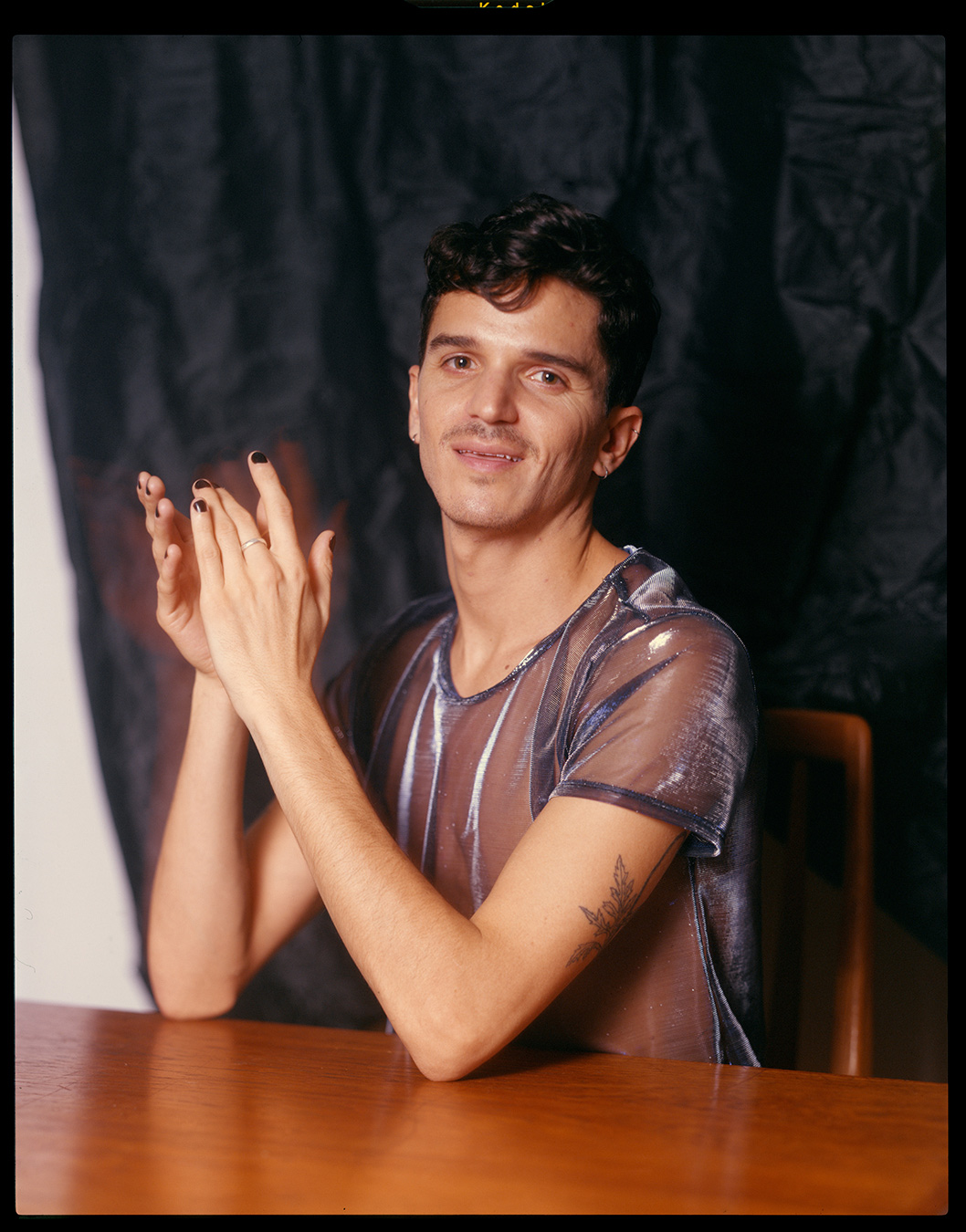

Ian: There’s also the dynamic between the sitter in the picture and [myself]. It’s such a stereotype to put yourself in a picture, but I think that’s inevitable, in a way. Especially when photographing people. You’re projecting a lot of your own thoughts, desires, and inquiries.

Olivia: That ties back to an idea you’ve spoken about—your subjects are a testament to someone’s ‘capacity for fiction.’ It’s less about who someone truly is, and more about what someone could be.

Ian: I’ve always struggled with that, because I feel both at the same time. I don’t want to diminish who someone is—absolutely not. Who they are is certainly very important to me. I don’t want to strip that away, but at the same time, a photograph can’t exactly do that. It can’t be that whole person, and show exactly who they are. I think that’s almost asking too much of a picture. I gravitate more toward going the other way, where a photograph can be this whole other universe you can create, and that person can be a character in that universe.

Olivia: There is a duality of identity. Something else I noticed is a dissociative quality in some of these portraits. Some of the subjects very clearly address the camera, while others look beyond the camera’s gaze. What is your interest in directing them in this way?

Ian: Expression is always really hard, because I use this big 19th-century view camera. Expression is the main indicator of that camera. When it was invented, the film was really slow. The shutter speed had to be really slow; it was a very long exposure. A person having a deadpan expression was purely a product of the mechanics of that camera—it didn’t make sense to smile for thirty seconds or longer. As cameras get faster, as shutter speeds get faster, the smile emerges as a phenomenon in a photograph.

There are two or more photos in the book where I tried to get someone to smile in a way that wasn’t necessarily a photo-y, say cheese smile. That was really hard. The idea of smiling for this camera is almost antithetical. It’s using the camera in a way that it’s not meant to be used.

Olivia: Fascinating–you contradict the initial function of that camera and reinvent it through a modern context.

Ian: A lot of different styles of music came from using an instrument in the wrong way, or in a non-classical way. That’s how house music was founded. [While] I still think my images are rooted in traditional portraiture, I’m really interested in using my camera in the way you would use a point-and-shoot, or using it in a way that it wasn’t designed to be used.

Olivia: This idea of the Ice Palace being gone implies a sense of loss, and maybe vulnerability. A lot of the subjects in the books feel self-possessed, while there are moments that don’t necessarily emanate that. Could you speak more about the title of your book?

Ian: I like the idea of them being self-possessed. I think they are sure of themselves in [the Ice Palace], even though it is melting. The Ice Palace is meant to be the setting that the pictures were made in. It’s a fictitious place, but also a symbol for queer space. It’s something I always go back and forth on, because [I ask myself] how productive it is to cordon off a space and label it. Is that more productive, or less productive? I knew that my characters were inside of this universe called the Ice Palace, and [it was] collapsing to the ground and being destroyed. It had to be rebuilt, and inevitably destroyed, and rebuilt again. It was what I was seeing in a lot of discourse in my periphery.

In 2016, when I was starting to think about this work, a mass shooting took place at Pulse, a mostly gay and Latinx nightclub in Orlando. In 2019, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, New York City adopted the moniker “World Pride” as the new framework for the annual pride march. To me, it feels like these events get flattened and absorbed together over time. They feel like revisions from what was built before, and maybe that’s necessary for growth, evolution, “progress”. Sometimes, the discourse is “We’re more alike than we’re different.” and sometimes, it’s very militantly “We’re different.” The politics around [queer discourse] get revised all the time. That’s what I wanted to get at with the Ice Palace being really precarious—very grand and palatial—but very easily destroyed, renovated. A lot of queer people live in precarity for various reasons, for things that aren’t solely about their sexuality: living situations, finances, their job, HIV status, and just generally their health [can be factors]. The ideas were colored by the US healthcare system, in particular. The Ice Palace is in the United States. [laughs]

Olivia: Could you speak to the pictures in the book that are not of people? Ones that are mostly interior spaces?

Ian: If the people in the pictures are the figures who populate the universe of the Ice Palace, then the ones without people are guideposts, or directions. Think of them as the Google Maps of the space. [laughs]

Olivia: There is an image of a wall of black-and-white framed photographs. The frames depict men that could be movie stars, perhaps. Where was this taken?

Ian: That’s at Julius’. The lore is that it’s the oldest gay bar in New York City. I noticed that a lot of gay bars have this motif of [a wall of framed photographs]. There are several gay bars that I have been to that have that exact kind of wall. The idea is that these are people who frequented the bar, or were there at one point. [The images] are meant to memorialize that. Most gay bars are always under threat of shutting down. It’s a miracle that they can stay open. A lot of my pictures that aren’t of people are set in gay bars, or other queer spaces like that. I [thought to myself,] ‘I am going to take this picture, and tomorrow this bar could be gone. I don’t know how long this place will be here. It’s not a given.’

Olivia: What do you think makes a strong image?

Ian: The strongest images are the ones that don’t tell me the punchline. They don’t tell me the answer to whatever the conflict is. The conflict is the characteristic element of a novel. To me, there has to be a conflict in a photograph. It has to tell a good story. The way a singular picture can be successful is by showing what the conflict is, and what a potential solution could be. I always need to leave with at least one more question. Good pictures leave you wanting more.