The photographer's new monograph explores human tendencies towards hedonism in a precarious natural world.

Mimi Plumb is an analogue-based photographer residing in Berkeley, California. Whether it be documenting labor camps in the ’70s in United Farm Workers, the anxieties and disillusionment of the Reagan era in Landfall or suburban youth in The White Sky, Plumb has a knack for taking a mystical and humanistic approach to issues within her state and the world at large.

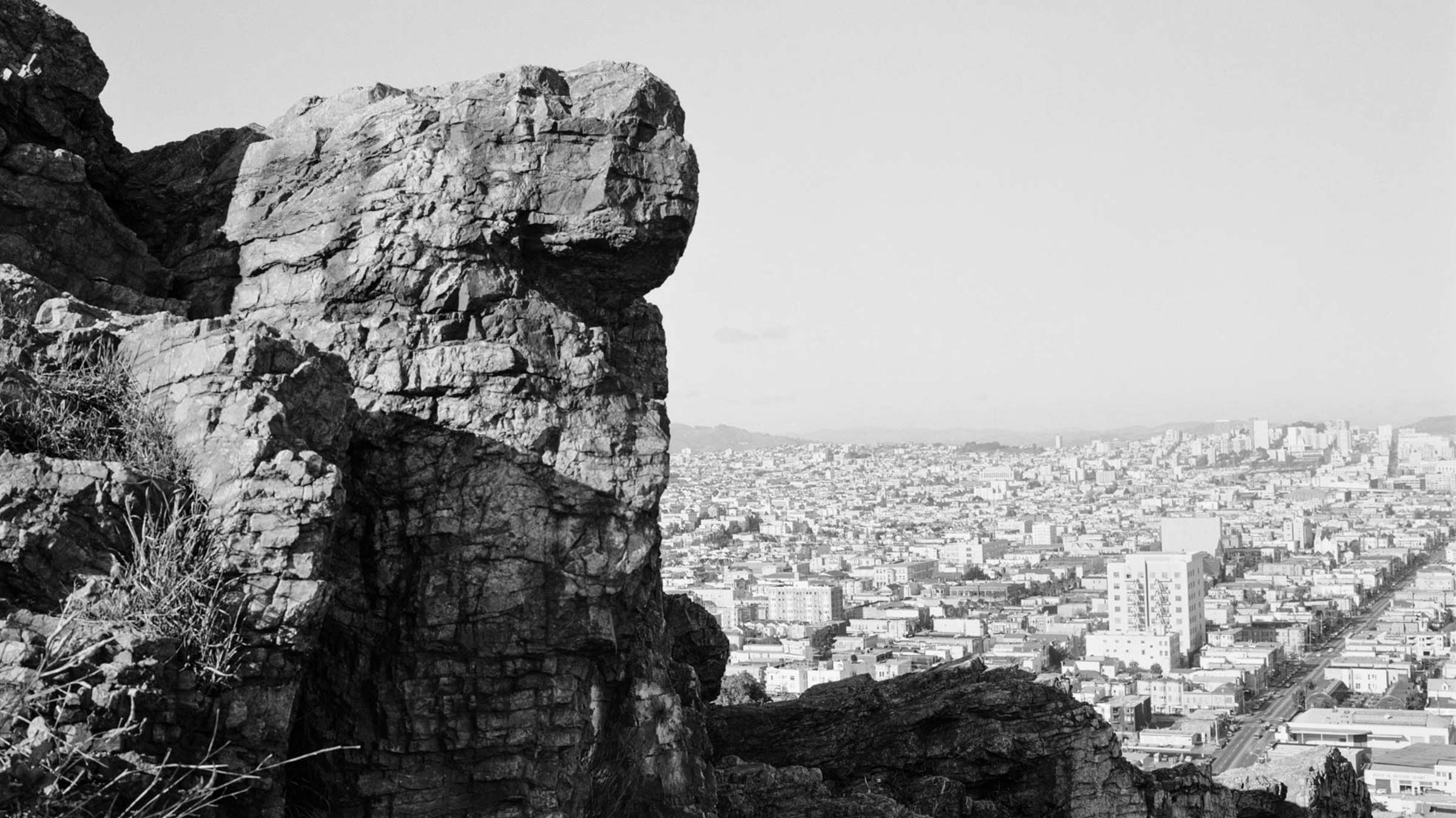

Plumb’s monograph, set to be published in the new year entitled The Golden City, is a series of images that frames subjects against the sprawling backdrop of San Francisco. Similar to Plumb’s other bodies of work, The Golden City is an ode to an earlier America—a rich and playful elaboration on the human condition, and its tendencies towards hedonism and spectacle. To say that this work largely references the exploitation of the natural world on account of humans would be reductive. While sculptural detritus and empty construction sites set the groundwork for this series, Plumb flips dramatic irony on its head by capturing subjects enthralled by events transpiring just beyond the frame. We are not in on the comings and goings within this world, but are sucked in nonetheless; left only with a sense of wonder at what could be bringing about such awe.

Olivia Noss: Decay and entropy seem to be a consistent thread throughout this work. Could you speak more to this?

Mimi Plumb: I had these various interests I was exploring in the ’80s. The Golden City is from the same pool of images that Landfall came from, but it has a different focus. I was really concerned about climate change and our disrespect of the environment. I wanted to know why these things were happening. The Golden City links wealth and power to climate change. It may be the entropy [of the landscape], but I am more interested in what we are doing to the environment. The people in this book represent the people living in this landscape of San Francisco.

Olivia: How does the anonymity of many of your subjects function within your work?

Mimi: There’s an ominous quality to photographing somebody’s back, particularly if they are unaware of it. There’s a certain energy to those images. When I look at them now, I’m surprised at how many pictures I’ve taken of people’s backs. I started photographing the landscape in the ’80s, but I didn’t feel like there was enough intensity to the work. That’s why I added subjects, and the flash [to my camera]. I wanted to add a certain immediacy that I wasn’t getting in photographing the landscape.

Olivia: In your work, the tension between the natural and man-made world functions as a signifier to an earlier America. Could you speak more about the optimism of the ’60s and its subsequent fall, in relation to when you made this work?

Mimi: Much of my work in the early ’70s stems from the optimism of the ‘60s. My family was pretty political—going to the marches, involved in the civil rights movement and the anti-war movement. It was a really exciting time. When I hit 18 in 1971, we were just coming out of this period of optimism. The ’6os was a really violent era, and the war in Vietnam was continuing.

Olivia: It feels as if there are two veins here: the one of vacant landscapes during the day, and an element of magical realism that emerges at night. The latter reveals hedonism in people—there is a sense of spectacle and pleasure. What was your interest in creating this tonal shift?

Mimi: I wanted to add that same immediacy to the work that I wasn’t getting from photographing the landscape. When you travel through the series, you really are traveling through the process of me making it. It represents the arc of my photography, from 1984 to 1990.

I wanted to instill a certain kind of psychological edge—that anxiety, that feeling of uncertainty, that fear. I think it particularly spoke to a personal anxiety that I was feeling in regards to what was going on in the world at that time, and I wasn’t communicating it through the landscape photographs. They would describe, but they wouldn’t [convey] that psychological angst, and so I looked for that in the people I was photographing.

Olivia: Would you say that the people you were photographing were a reflection of your own mental state?

Mimi: I wasn’t actually thinking of it in that way. I really felt like, at the time, I was photographing [in a way] that was more documentary. It was a portrait of my anxiety about society. It was a portrait of anxiety about the future.

Olivia: What do you think makes a strong image?

Mimi: I think it’s really hard to pinpoint. It’s something I feel when I look at an image. There are some images that I feel in my back.

Olivia: Images that evoke a visceral response?

Mimi: Yeah, visceral. There’s just this sense of something that rings true. Images that ring true, to me, are the ones that are the most powerful.