For Document’s Summer/Pre-Fall 2021 issue, the designer discusses scandal and subversion with Thierry-Maxime Loriot

Manfred Thierry Mugler has a thick mustache that stretches handsomely across his upper lip, a neatly shaven scalp, and muscles that beg the buttons of his shirt to pop right off. He is likely the brawniest, and possibly the greatest, living provocateur of fashion. Ever since he blazed into the world of womenswear in the early ’70s, Mugler has become synonymous with feminine allure—the powdery sweet scent of his Angel perfume, his otherworldly garments constructed in body-conscious silhouettes, and the roster of women warriors who have worn them. His runway spectacles were occupied by Naomi Campbell and Linda Evangelista in exaggerated power suits and robotic corsets. Though the designer himself has officially retired from fashion, he did, however, make an exception for Kim Kardashian, spending eight months creating the infamous latex dress dripping in beaded crystal that she wore to commandeer the Met Gala in 2019. His motorcycle bustiers and leather masks that were once deemed controversial are now widely emulated and celebrated for their transgressive sensuality.

This fall, the touring exhibition and book Thierry Mugler: Couturissime will be presented at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris as imagined by Thierry-Maxime Loriot, the Canadian model-turned-modernist curator who has earned a reputation as one of fashion’s greatest storytellers. Ahead of the exhibition opening, Mugler and Loriot discuss scandalizing journalists, embracing extremity, and the pleasure of subverting haute couture’s pretentious side.

“For me, to design an appealing gown that would also appear to be simple, but very flattering, was an exercise to reach perfection. Haute couture or not, I wanted to see things through to the end, like a piece of music that requires tempo, a rhythmical stage.”

Thierry-Maxime Loriot: You presented a fashion that was very free, inclusive, and provocative, a world of its own that shook up fashion, before retiring from prêt-à-porter and haute couture in the early 2000s. Looking back, would you consider that you had an anthropological, even prophetic, vision of what fashion would be? Did you mean to create fashion that would mirror society?

Manfred T. Mugler: My visions were always based on human beings and nature. There is nothing political about my inspirations, they are instinctive. What inspires me most, and always has, is infinite possibilities. The search for beauty, how we can transform ourselves, has always fascinated me. Every civilization through the ages is a constant inspiration. I was never an intellectual who wanted to drive home certain points or to break codes, even though that is what happened in the end. My approach was to propose amazement, discoveries, a plurality of beauties: people who had the courage to be themselves. As a child, I wanted to create my own world and to live in it, to make it always more beautiful and magical, and that hasn’t changed.

I love extreme personalities, they fit what I wish to express. My approach is very instinctive and obvious, but it is not meant to be transgressive. I have always looked for all forms of beauty. All the bodies that I ‘perfect’ are perfect even without my enhancements; however, I oversize them as I adjust the waist, the shoulders, the entire silhouette. Kim Kardashian is one example. She is a callipygian beauty, a timeless, almost bygone female ideal. I don’t believe in a single form of beauty. The beauty of our bodies—big, small, tall, skinny—whatever the size or type, we have to accept them and be in harmony with them.

Thierry-Maxime: Why did you try your hand at haute couture in 1992? You came up with designs that were both minimalist and maximalist.

Manfred: For me, haute couture was an additional, more sophisticated tool. I was fascinated by its minimalist yet lavish side, and by the idea of working for months on perfecting a single piece for a specific woman. My first prêt-à-porter shows had included some highly elaborate haute couture pieces. I loved to play with the pretentious and bourgeois character of haute couture, to make it evolve. The time had come to show something different and to give it a breath of fresh air, even a good jolt! I wanted to create clothes that could ‘stage’ our daily lives. For me, to design an appealing gown that would also appear to be simple, but very flattering, was an exercise to reach perfection. Haute couture or not, I wanted to see things through to the end, like a piece of music that requires tempo, a rhythmical stage. It was a ricochet that guided me from one collection to the next, pushing me to go even further. I like to tell common human stories in different ways. I was called ‘provocative,’ but I never realized it immediately, only afterwards! The idea was not [simply] to shock, but to shock in the right way, to shake up the fashion world and the media, who took themselves much too seriously. It was fun to see the bourgeoisie and the journalists being somewhat scandalized.

Thierry-Maxime: You controlled all the creative facets of your collections, your pictures, and the staging of your fashion shows—from hairstyles to makeup and accessories to the soundtrack—as well as your advertising campaigns. What would come first: the idea of the garment or the story you wanted to share?

Manfred: It was like the snake biting its tail: both at the same time! The shows inspired the direction of the photography. I have always liked uniforms, with their patriotic, glorious side, the flags, parades, the circus of power and authority, the futuristic suits, the strength and impact of clothes; not for their political qualities, but always for their graphic and aesthetic beauty. I didn’t travel to the USSR or to other countries to make a statement or to champion an ideology. My goal was to create breathtaking images in incredible locations that were newly accessible and still hard to reach, in perfect harmony with my creations. I was never interested in fashion, but rather in its daily staging. I wanted to bring magic to the world by creating refined, fleshed-out objects in places and sets that are exceptional but real, urban, or natural. My photographs are a vertiginous, poetic point of view, looking out from reality and into a magical world.

Thierry-Maxime: Your archives are highly sought after, rarely loaned, and even less frequently exhibited. A whole generation of young stars, initially led by Lady Gaga and Beyoncé, and now Cardi B and Kim Kardashian, wear your outfits, which remain as coveted as ever 30 or 40 years later.

Manfred: That is very touching and rewarding. Indeed, I wasn’t making fashion and I wasn’t following trends! That allows me to tell a story and perpetuate it, in a way. I enjoy seeing young people inspired by my work on social media. It’s a creative emulation that shows the timelessness and the originality of my work.

Thierry-Maxime: Your fashion does not draw on the history of fashion, but rather on the history of cinema and music. What are your greatest sources of inspiration?

Manfred: The Golden Age of Hollywood, with its decors—nature, recreated inside the studios and retouched to The films of Carl Theodor Dreyer, Josef von Sternberg, Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Federico Fellini, and Luchino Visconti left their mark on me, and the photographs from Cecil Beaton, Horst P. Horst, and George Hoyningen-Huene. The costumes made by Travis Banton for [Sternberg’s] The Devil Is a Woman, and those created for Cleopatra, the 1934 Cecil B. DeMille movie, are a reference, as are the creations of Adrian [Adolph Greenberg], and later those of Charles James, Cristóbal Balenciaga, Ossie Clark, and Rudi Gernreich. In music: Philip Glass, but especially the psychedelic works! The concerts I attended by Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin—both amazing performers—were a revolution, as were performances by salsa diva Celia Cruz, Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick, and Ike and Tina Turner, who together brought pure, hair-raising energy. Bowie as Ziggy Stardust was an incredible and sublime trip, as was Marlene Dietrich’s final concert at the Espace Cardin, a minimalist wonder of emotions and subtleties that was delightfully touching.

“I didn’t travel to the USSR or to other countries to make a statement or to champion an ideology. My goal was to create breathtaking images in incredible locations that were newly accessible and still hard to reach, in perfect harmony with my creations.”

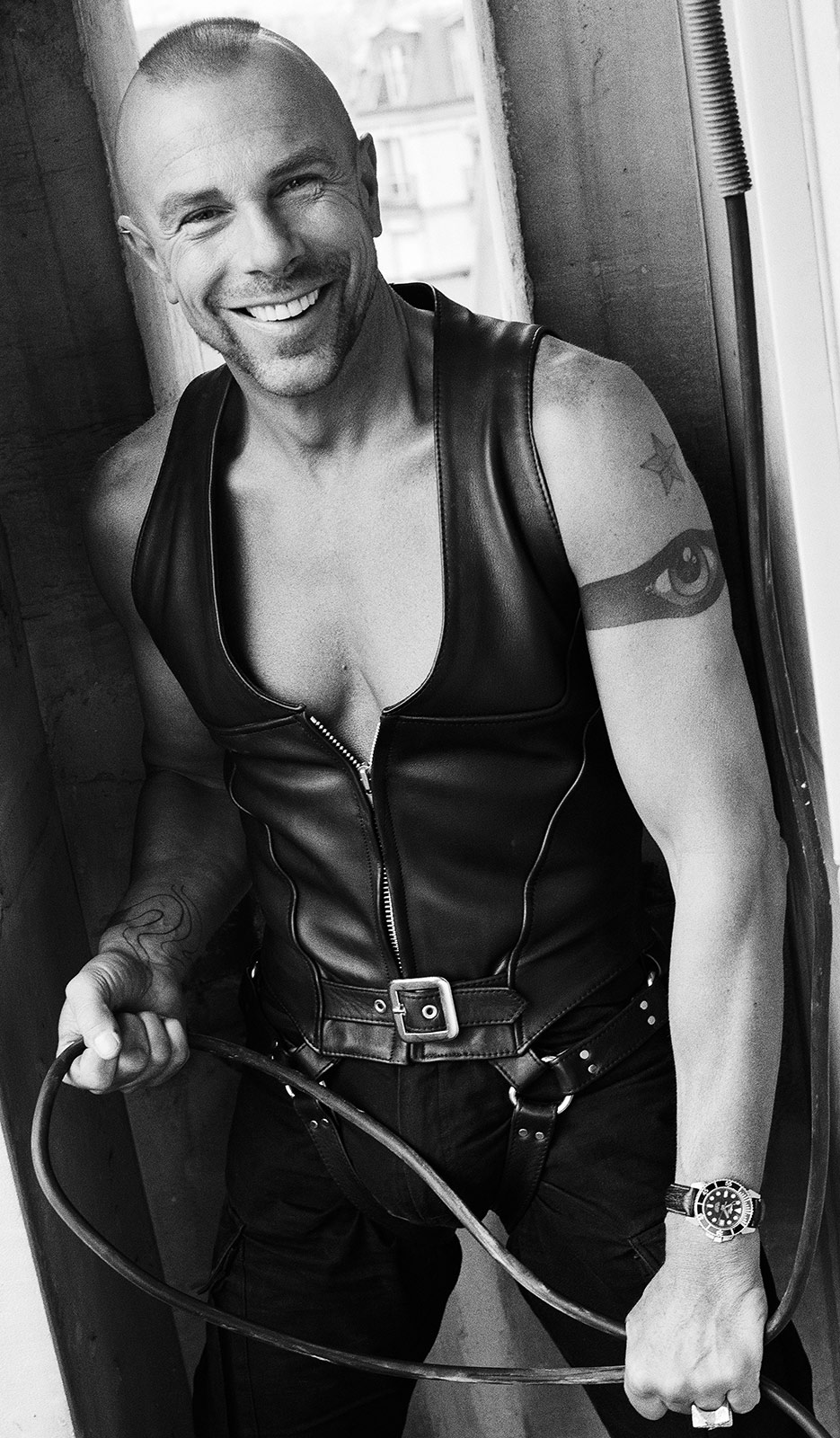

Thierry-Maxime: Several of your creations refer to the world of S&M, with latex, rubber, leather, masks, whips, and vertiginous stilettos. Did that universe inspire you, or were you trying to create a sexual fantasy machine?

Manfred: I made pieces that were cheeky, pushed to limits, but never vulgar. I wanted to reveal the animal or vital energy within. If I create a suit or a robot, life—the woman—must emerge; the animal instinct is stronger than anything else. I love transforming bodies into heroes. When I made the costumes for Macbeth at the Comédie-Française, the actors were not athletic. I transformed them into extreme fighters. Clothing has to magnify characters, it has to tell a story. I enjoyed the blending of genders, the highly effeminate, androgynous men who paraded for me, but also the very masculine women. When I was told that I was making clothes for sex shops, I found it quite amusing, as they were extremely refined. It is funny to see that what was shocking not so long ago has become normal. Even first ladies wear 12-centimeter-high stilettos nowadays … The lavish manes of my superwomen were widely mocked, but now many women wear hair extensions. The latex suits, the tightly waisted jackets, the exacerbated femininity—for example, vinyl leggings make legs appear statuesque, as if they were lacquered. I think these are great, classic, flattering fabrics that I lent cachet to. Perhaps I was right after all?

Thierry-Maxime: As early as the 1970s you wanted to create your own perfume. What motivated you?

Manfred: For me, perfume is one of the tools we can use to bring magic into people’s everyday lives. It completes a person’s universe, their aura, in a way. It is the final touch. From the beginning I wanted to create a gourmand fragrance, with chocolate and candyfloss. After hundreds of trials, Angel was created. A large number of today’s perfumes are its descendants. At the time, all the great perfume houses launched a new fragrance every six months, but the mythic perfumes were lacking, and so were the bottles that people yearned for. Those that marked my childhood, such as Shalimar [Jacques Guerlain] or Joy by Jean Patou, were beautiful collector’s items. Angel was a work of prowess and the result of complex research. Its hand-polished crystal bottle in the shape of a blue star, the push button, even the refill source to preserve and reuse the object: Everything had to be invented for that bottle. It presented a real challenge for the great crystalware makers, the ‘alchemists’ who worked passionately on the project. In the early 1990s, to recycle a perfume bottle was unheard of! The success of Angel is also due to Vera Strübi, the first president of Mugler’s perfume division, and to the teams who devoted themselves to championing it throughout the world, the Mugler army!

Thierry-Maxime: Do you think the word ‘extreme’ describes you best?

Manfred: I have been, among other things: a dancer, a vegetarian hippie, a yogi, a globetrotter, a couturier, a perfume maker, a producer, a photographer, a songwriter and scriptwriter, a stage director, and—a bodybuilder. So, logically, I have undergone a complete physical transformation. I follow my dreams and life quests. So yes, I do love extremes. And I am [extreme]! [Laughs] Of an extreme discipline, certainly.