For 'A Sidelong Glance,' the photographer worked with Ralph Ellison's collection of Central and West African sculptures, weaving together the contemporary and the ancestral

John Edmonds reflects on his practice with the measured assurance of an artist whose picture-making is infused with deep historical understanding—a disposition palpable even as his voice is muffled by the low roar of a train passing near his Brooklyn studio. As we discuss the 31-year-old artist and photographer’s latest collection of work, I’m taken with the precise yet poetic diction through which Edmonds relates the ethos and ethic behind his first solo museum exhibition—conjuring mental images of his pictorial process that are nearly as rich and illustrative as his actual photographs.

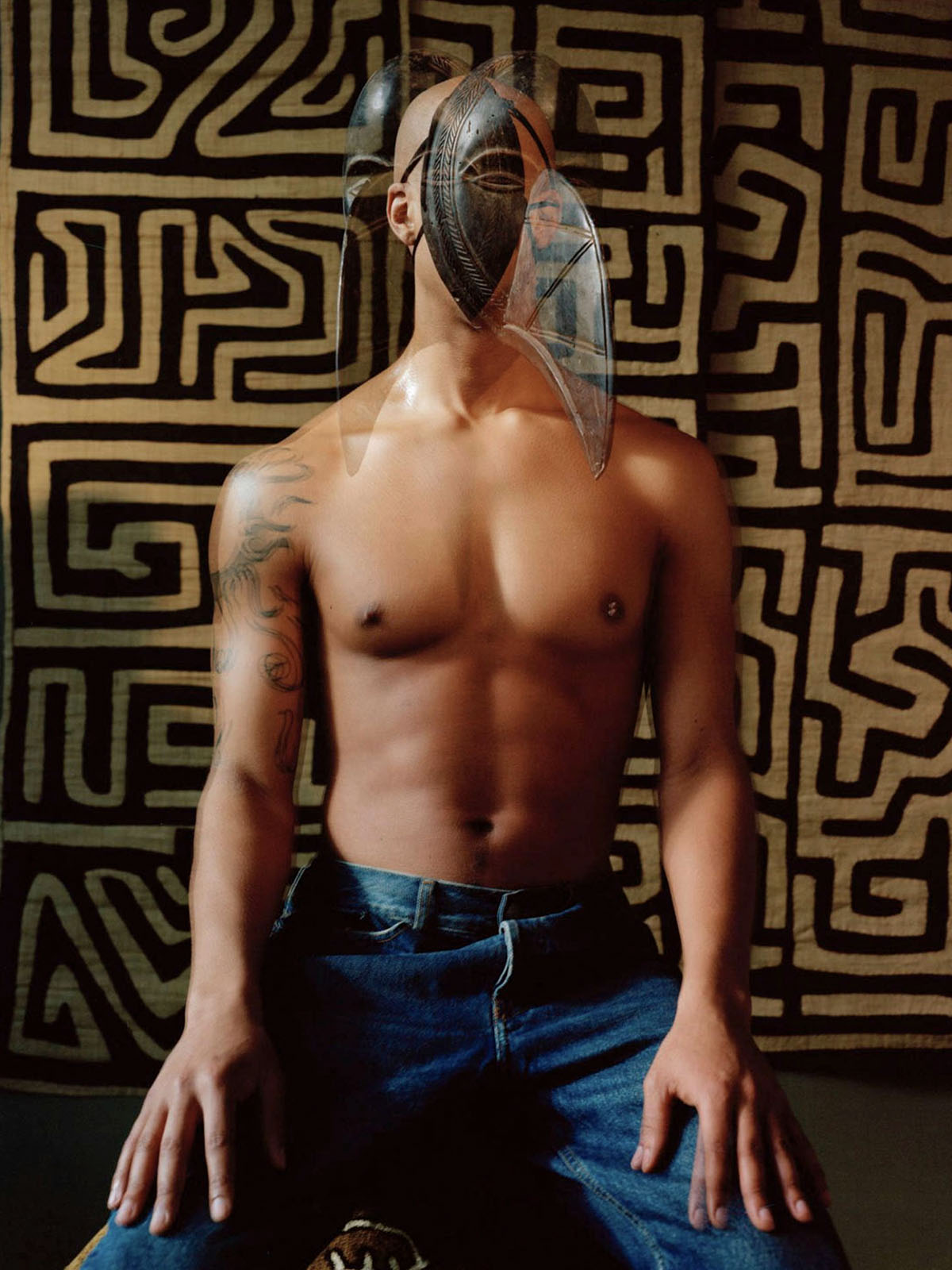

That same poetic precision is evident throughout A Sidelong Glance, currently on view at the Brooklyn Museum, which explores representation and Black identity in the African diaspora through a series of photographic portraits and still lifes. To create new pictures for this exhibition, Edmonds engaged directly with the Brooklyn Museum’s Arts of Africa collection, photographing sculptures donated to the Museum from the estate of the esteemed African American novelist Ralph Ellison.

Edmonds acknowledges that working with the late writer’s collection was as daunting as it was thrilling. But as the exhibition makes evident, he was able to transform this challenge into a compelling dialectic—harmoniously weaving connections between the contemporary and the ancestral, the real and the immaterial, and the sentimental and the spiritual. The resulting photographs are opulently layered and visually lush, but never in a way that confounds meaning. Edmonds consciously uses the power of his lens to emphasize and reify the spirit or presence of his subjects, whether they be members of his creative community in New York or the sculptures and masks of Central and West Africa.

All of these juxtapositions meet back in the same fundamental place—a reimagining of what identity and authenticity looks like within the Black diaspora. Edmonds sees his photographic practice as an act of community building, something he hopes will “lead [us] to a stronger, more inclusive, more insightful and more loving future.”

Biz Sherbert: What was it like working with the Central and West African sculptures from the Arts of Africa collection?

John Edmonds: Working with the collection from the Brooklyn Museum was very exciting and terrifying because it’s the collection of Ralph Ellison, the renowned writer and essayist. As I worked with the collection, and as I got closer and closer, I realized how valuable it was. I had to work with the conservator—they were the one who touched the objects, who put the objects within the frame and removed the objects [from] the frame, so it was a collaborative effort in many ways. The only restriction was that I and the subjects [were] not able to physically touch the objects. Throughout the evolution of the entire project, I had been able to touch and inspect all of the objects that I used. The levels of restriction were in some ways maddening but I had to find a way to work within those confines.

Biz: I’m curious about the origin of the concept—was that collaborative or did it occur to you on your own?

John: The objects in the work and the historical precedent it addresses spans centuries. [This project] began with my inquisition into understanding these earlier decorative art objects, and then moving to other objects that are traceable to different tribes, ethnic groups, and destinations within Central and West Africa. The evolution of the project also shaped my evolution in the understanding of the African art objects; in terms of authenticity, religious and ritual practices, and what these objects are used [for]. As someone who grew up with a strongly religious background, objects of sacredness or spiritual power have always been of interest to me.

The project comes from so many different places and you can see that throughout the show. [The works] vary in scale, they vary in object type, they vary in where they’re acquired, collected, or borrowed from—it’s not singular or myopic in any way. It’s a work that continues to expand and expand, and the viewer’s understanding should expand and expand as they look through the show—at least that is my aspiration.

Biz: You’ve brought up the idea that realness and authenticity can be dictated through care and love towards a person, place, or thing. I really loved that idea especially in relation to objects like the ones you’ve photographed here, objects that carry immense spiritual and also sentimental value as they’re passed down through families and generations. How does this relationship between care and realness inform A Sidelong Glance?

John: Starting this kind of grand project with the African sculptures is the traceable beginning, but something that the viewer may not know from looking at the show is that I grew up with objects like [those] in the earlier pictures—such as Tête de Femme or Still Life II—in my own domestic space when I was a child. So there’s a sense of familiarity [with] those objects and an attraction that is based on what many serious ‘scholars’ of African art would consider kind of a caricature.

There is a campness [to these objects] that [is] very interesting because there is sincerity to that—many of these objects are handed down from one member in a family to another family member to another family member. In that, authenticity may not be discernible or traceable to an ethnic tribe in Africa but [rather] through this Black family that lives in Brooklyn [and] has been passing these objects down. There is a sense of authenticity and realness in that.

In photographing these objects I wanted to assign them the same kind of power and value. Not that it’s not already there, but [I wanted] to affirm that power and value through the camera. [At] the very end of the show, there is a grid of photographs that are a documentation of Ralph Ellison’s art collection in this museum photography style. I applied that same kind of language to the earlier objects.

I’m interested in [the] gap in understanding these objects as real or true or valuable or having a place, and the place that they actually hold within our lives. That’s my first and foremost interest.

Biz: You break the fourth wall, so to speak, in several of the photographs in this exhibition, like Female Nude and Untitled (Marion & Yaure Mask), by including bits of photoshoot setup in the frame. Can you explain the significance of revealing the process of picture-making in your work?

John: Many of those decisions are pictorial because often when I’m working—whether it’s in a studio space, or a space in the world where I’m making a kind of makeshift studio—this idea of cultural production, and production as an intrinsic part of the work, is something I want the viewer to see and to feel. [I want the viewer] to understand that [photography] is rigorous, hard work.

There are layers and layers of labor [within] these objects that [can be] so deceptively simple. In the same way, photography is understood to be this simple thing that is actually quite compressed in terms of sequencing, creating relationships between images, [and] on a fundamental level, crafting an image. These are pictures that are crafted and that is something that the viewer should be aware of as they move throughout the space and think about their body in relationship to the work and to the objects.

Biz: I feel like the average museum visitor might look at a painting and be able to intuit, via the layers and the brushstrokes, the work that they believe went into that painting. I don’t think people necessarily have that train of thought when they view photography in a gallery space.

John: Not at all. I think it’s something that many artists working within the photographic medium interrogate at one point or another. Ultimately [with] photography, there’s such a strong invisibility in terms of the work that goes into making a picture—so much of it’s invisible, so how can I make that rigor felt throughout the space? So much of that comes from, again, returning to the source and parsing what it is that we’re actually engaging with. Peeling back those layers is very important.

Biz: I love the interaction between the contemporary clothes worn by your sitters and subjects and the much older African sculptures, masks, and textiles. How did you consider the fashion and styling of your sitters when you composed these photographs? Was it something more organic or deliberate?

John: It’s organic. There are moments in time in the making of the work where I ‘auteur’ the subject. For example [in] Anatolli & Collection, these are the leather pants that Anatolli was already wearing. Leather is something that recurs in some of the pictures [along with] this idea of leather as a surface that conjures touch, feeling, and desire. I like that relationship of people [as they] exist in the world—this is how they are, this is who they are, and when they enter into my pictures I don’t want to make them someone who they are not.