The LA-based artist is writing the blueprint for a better manhood by looking to the past

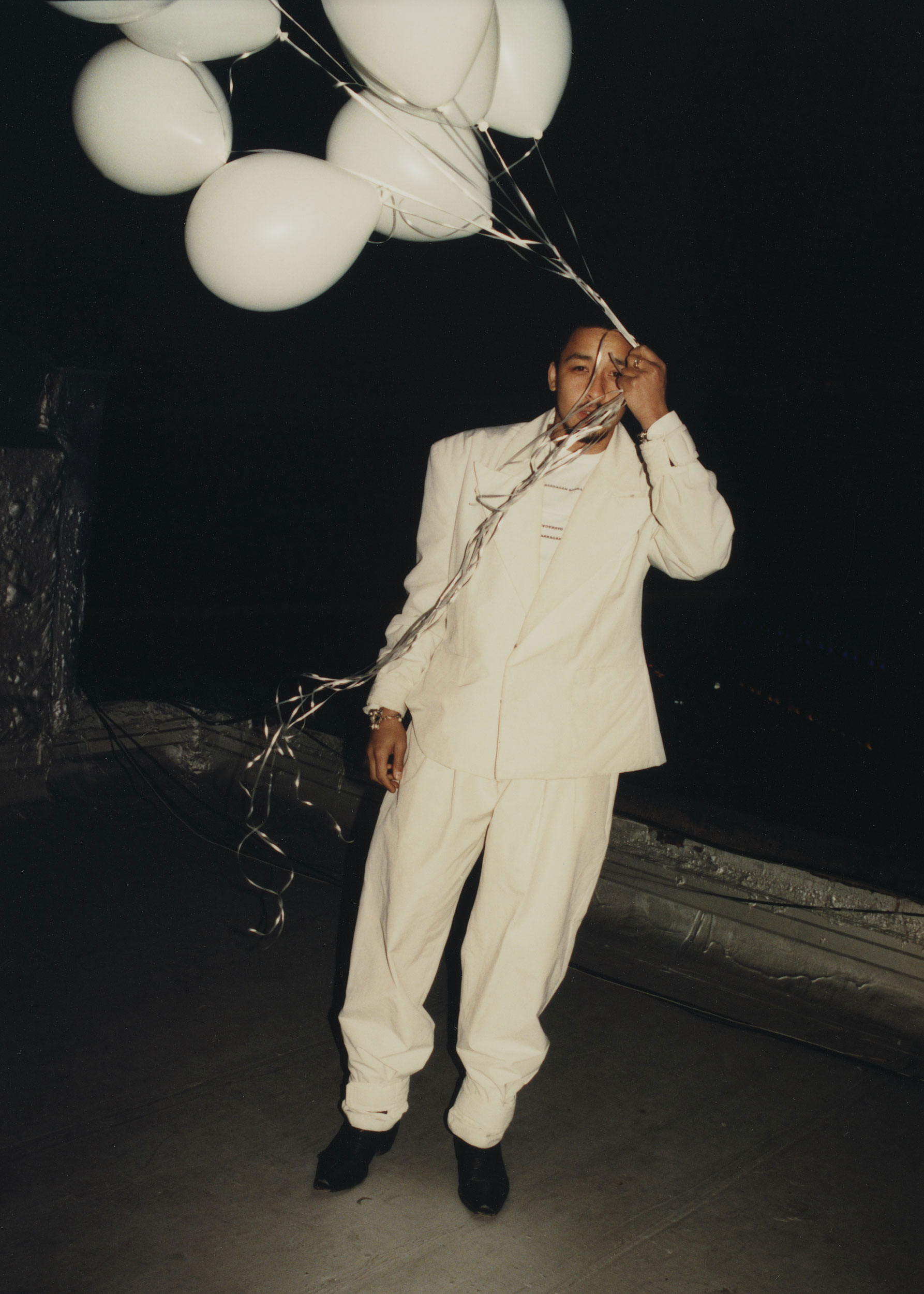

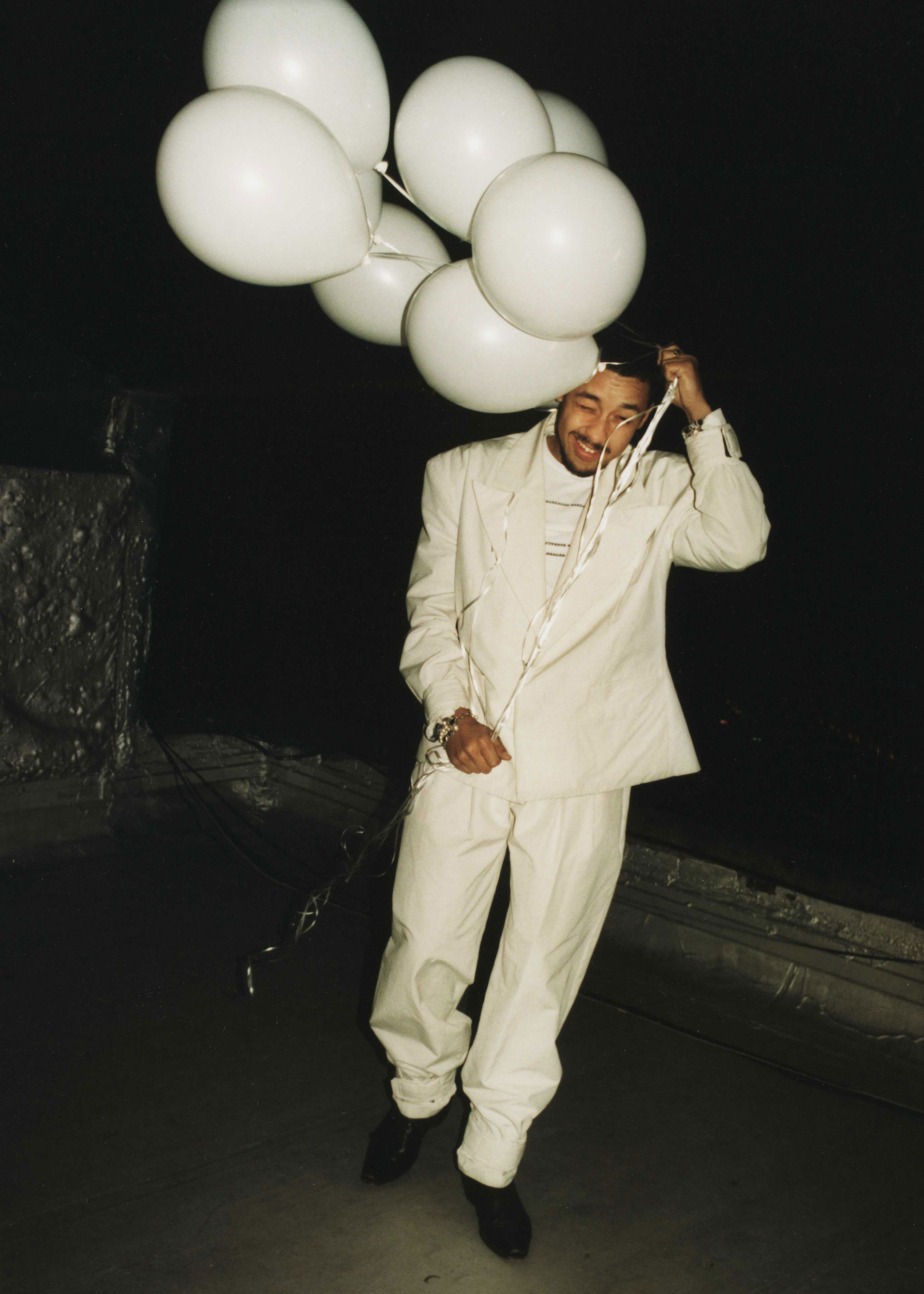

Onstage at the Bowery Ballroom in early February, Dijon didn’t know he was dancing. The LA-based artist jostled around, strumming his guitar and rocking, back and forth, in painted cowboy boots. It was his first tour since going solo from his last project, the acclaimed duo Abhi//Dijon,and he had sworn off dancing before it even began. “I just would never do that,” Dijon told Document a few hours before, in a discussion about his adjustment to the live performances that, he promised, would be a lot of standing still. In New York, at least, he lied.

Sure, none of his movements were particularly calculated. They weren’t worthy of Normani’s “Motivation” music video, nor as carefree as the stumbling around that Scarlett Johansson performs in Marriage Story and across the Internet. But they were there: Dijon was being choreographed by his subconscious as his signature, baritone rasp broke into the mic and bled through the speakers around the crowd, who followed his awkward moves with their own. Dijon was swaying—a kind of dancing, whether he knows it or not.

There are other things Dijon doesn’t know he’s doing. For example, when he playfully threw rose petals over the crowd—really, the only gimmick in an otherwise straightforward set—he didn’t seem to recognize that he’s a heartthrob in cowboy heels, that the cheers from several hundred people packed into the room were not only intended to quell his anxiety, but also to voice their own thirst. And Dijon definitely doesn’t know that he’s dissecting masculinity in his music—but that’s exactly what’s helping him do it.

Dijon’s work falls most neatly between indie pop and folk, but he’s heavily inspired by R&B, the musical lane where men have, historically, had the most freedom to express tenderness. (In fact, D’Angelo, whose high-gliding vocals betray the great frame of his body, is one of Dijon’s all-time favorites.) The basic unit of contemporary R&B is desire, and it is that which Dijon has set over beats and strings, song after song, to forge his discography: a handful of singles and one complete song collection, Sci-Fi 1. “Drunk,” for example, is a desperate cry for someone after a rowdy night of drinking. In “Skin,” he’s hot and heavy in the sheets with someone, getting turned on by the tender way she holds him. “Dog Eyes” relays the cyclone of emotions he feels as he remembers a bygone lover.

Part of what Dijon always seems to want is to turn back time; in “Cannonball,” he sings as a child coming to grips with a crush on his friend. The ordeal overwhelms him: The pair swim in a lake, and Dijon watches the other crater right into the deep. Young Dijon wants to be held, “without grace and ungently.” Then, in the bridge, each of Dijon’s syllables marks a drumbeat of anguish. The guitar strings are yanked about. It’s a simple turmoil that young Dijon is reckoning with—wanting someone from across the water—but the mid-song tantrum is proof of a profound realization about the state of love: that it’s something like a great, uncontainable wave, and that getting hit by it can be as painful as it is exhilarating. To sum it up, the word “crush” is pretty spot-on.

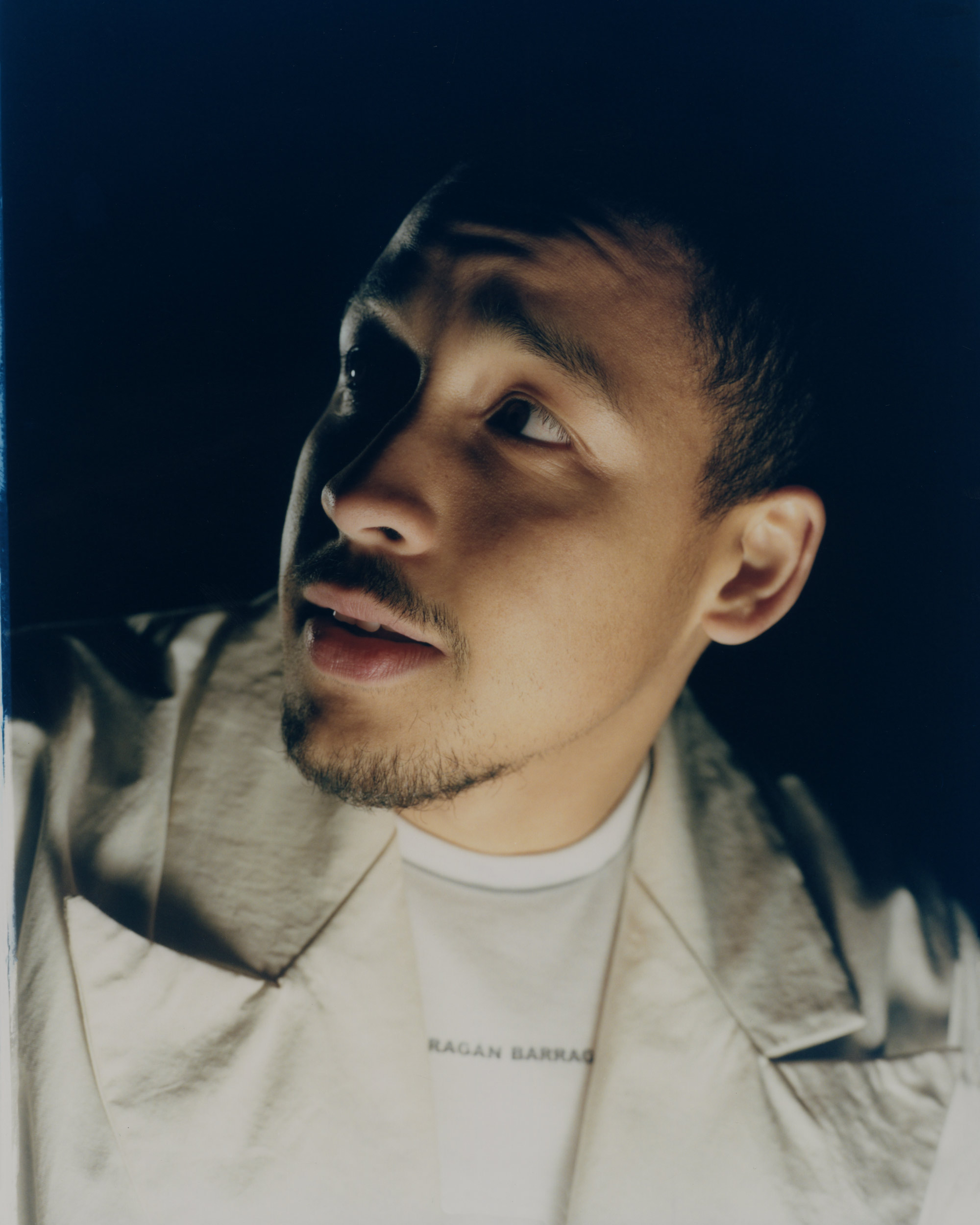

“It’s just very natural for me to write about what I think is interesting,and mostly, human brains are interesting,” Dijon said. “The capacity to feel and to hurt and to hurt other people, emotionally, is very interesting to me.”

Of course, the capacity to hurt is a key feature of a gender known, at its worst, for an unbearable aptness for violence. Scholars have long held that men form their gender performance partially out of the threat of being seen as womanly; as early as 1979 one psychologist wrote that, when men believed their sex-role is threatened, they tend to overcompensate with actions they’d consider masculine.

These things are changing, somewhat. For Dijon, the right mindset is an authentic apathy to recognizing his performance—onstage, or elsewhere. And that just might be a good theory for an alternative, less-violent manhood. “I can’t confidently say that there’s an intentional subversion,” Dijon said. “But I will say I’m happy that it’s interpreted that way to a degree, because the last thing I’d ever want to be seen as is just like, machismo. It’s just so dead to me.”

Partially, that’s because his upbringing never really forced him to be macho at all. “That just wasn’t my experience,” he said. The son of military parents, Dijon grew up in a lot of places, but Maryland, where his mom lives, headquartered his boyhood. One of the artist’s most successful songs, “Nico’s Red Truck,” is a flashback montage that blurs through his upbringing there: Dijon peddles around on his bike, jokes with friends, and whirs through the suburbs in a dark green Honda civic. A moment before the last chorus, in the memory he’s most focused on, Dijon parks his bike in a field under a glowing moon and realizes his first paycheck has been soaked through with rain. But everything’s still dope; in fact, the rain made it better: “I loved the smell,” he sings, “so I just inhaled.”

“Petrichor” is the word for the scent Dijon is remembering, and it makes sense that he is. Coined in 1964 by some romantic scientists, it’s a mash-up of the Latin root for “rock” and the Greek word “ichor”—the ancient blood of the gods. In short, a falling rain brings out the scent of an old, crypt-kept substance that’s left us, and this is why we love it. It’s nostalgia, pleasant and heartbroken, for what’s long gone. Much of Dijon’s music has that same sense of looking back. He wrote “Nico’s Red Truck” about one of his most pervasive fears: losing his memory. “I don’t remember things well, and I hit a little point where it actually scared me a lot,” Dijon said.

But if “Nico’s Red Truck,” an older track, indulges his anxiety about losing his memory, his later songs mourn the losses the man has endured. His latest, “Crybaby,” deals with the fear of losing a lover, and as he pleads with her not to leave, he undergoes a particular change: He turns back into a boy.

“Crybaby” is designed to devolve. It begins with white noise and then the jaunty drums bounce forward, setting a lively path into the chorus’s sing-shouting. “Well I don’t mind if you see me cry,” he sings, reluctantly, and then adds: “You know I can be your crybaby, yeah, cryin’ out to you and stuff.” The stuff here is, well, emotion, even if that’s not something Dijon, a man, is supposed to dwell on; in fact, the use of the word “stuff” is a reminder that men are coded with few acceptable emotional responses to, well, anything. And the move to childhood, Dijon’s lyrics seem to argue, is necessary for the shift to vulnerability. For Dijon to be what his lover needs, he has to molt his learned manhood and become, once again, a child. It’s not just a reticent path forward for other men; it’s also an explanation of the kind of Never Land in Dijon’s mind: that perpetual boyhood he inhabits that allows him to keep reinventing what it means to love, and write love songs, as a man.

It’s hard to talk about the future of a young artist, especially when his lyrics are so necessarily rooted in the past. But Dijon can be forward-thinking, too. His upcoming album, titled How Do You Feel About Getting Married?, is due out later this spring. Rather than a full-throated proposal, the question teases adulthood, in the gentlest of interrogatives about whether his lover might be ready to take part in such a grown-up ritual. It’s the kind of question a young kid might ask a crush on the playground, or at the mall, or after a long bike ride, out of nowhere and just because. The stakes are low for these kinds of questions, and the answer, of course, could be no. Dijon, it seems, could live with that.

Stylist Assistant Alex Picon.