The artist captures the breadth of Black womanhood in her video installation 'The Giverny Suite'

It is 1976 at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland. Nina Simone sits down at her piano to play Morris Albert’s easy listening dirge “Feelings.” In Ms. Simone’s hands, what was once a saccharine, hollow tune is now a mesmerizing piece of music with her virtuosic piano playing, asides to the audience, and thousand-yard stare.

“The footage of her performing in Montreux, this rendition of ‘Feelings,’ to me it’s just— it’s one of those videos that I would come back to, over and over again, throughout the years. Thank God for YouTube,” says filmmaker Ja’Tovia Gary in our recent correspondence. “It’s easy to dismiss it as, ‘Oh, she’s high, or she’s crazy,’ but to me, she’s engaging with the audience in a way that feels very sophisticated, and there’s an air of distance that is there. But she’s also not going to let you forget that she is brilliant.”

Nina Simone figures heavily in Gary’s newest work The Giverny Suite, a part of her show flesh that needs to be loved at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York. The acclaimed filmmaker’s immersive video installation slices and fuses footage of the aforementioned Montreux performance of Nina Simone with the artist at Claude Monet’s estate in Giverny, France, and interviews with Black women Gary meets on a street corner in Harlem. Drawing from her personal experiences and a wider cultural context, Gary’s films are an immersive, multi-faceted exploration of Black womanhood in America, exploring joy, love, and fear with equal amounts of care and consideration.

The Giverny Suite began as Giverny I (Négresse Impériale), a six-minute film Gary created in 2017. Described by the artist as a “kernel” of the later collection of films, Giverny I (Négresse Impériale) is surreal and intimate, juxtaposing scenes of Gary in Monet’s Giverny gardens with audio from Diamond Reynolds’s Facebook Live recording of her partner Philando Castile’s 2016 murder at the hands of Minnesota Police. The resulting film seamlessly flows together due to Gary’s virtuosic edits paired with a chopped and screwed rendition of Louis Armstrong’s “La Vie en Rose,” which was created by Nelson Nance, Gary’s childhood friend from Texas turned creative collaborator.

Upon the completion of Giverny I (Négresse Impériale), Gary knew that “there was more to the conversation around the various concepts and themes presented in the short,” saying, “I knew that there was room to expand and continue to consider Black women’s bodies within a context of capital and colonial expansion—the safety of our bodies and our lives in a very quotidian context—but also all that we bring to the table in terms of creative production, the brilliance, and virtuosity.” In the three years since she began this project, Gary has received numerous accolades for her work; another fragment of the video installation, The Giverny Document (Single Channel), was selected for screenings at the Locarno Film Festival and the Camden International Film Festival, picking up the Douglas Edwards Experimental Film Award from the Los Angeles Critics Association along the way. Now, Gary is showing a video installation version of The Giverny Suite with concurrent exhibitions at Paula Cooper and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, leaning into the possibility of the “mise-en-scene” provided by gallery space.

At Paula Cooper, the exhibition consists of two rooms. The larger space shows The Giverny Suite, and Gary’s film is projected against sloped walls with concealed frames occasionally coming into view and highlighting the faces on screen. Along with the soundtrack, the three-walled video projection envelops you in the world Gary creates on screen. In the second room, Gary mimics a family living room, a nostalgic scene that is simultaneously comforting and loaded with hidden meaning. Her multi-media sculpture Precious Memories sits to the right corner, facing a large, lived-in recliner. Precious Memories consists of a stack of three televisions; the screens each display heavily edited footage, including VHS-filmed scenes of the 1995 funeral of Gary’s stepfather. In conjunction with the film element of the video, the domestic setting surrounding Precious Memories considers “interior violence, the violence of the intramural, and how the practice of mythologizing the past often obscures the truth or the reality of our lives in favor or a more sanitized or rose-tinted view of history. Obscuring the reality of that violence prohibits us from actually healing and moving beyond it. Think about the living room space …The nexus of the contemporary domicile where we live in relation to one another and how we define ourselves and our relationships to one another in this very intimate, interior space.”

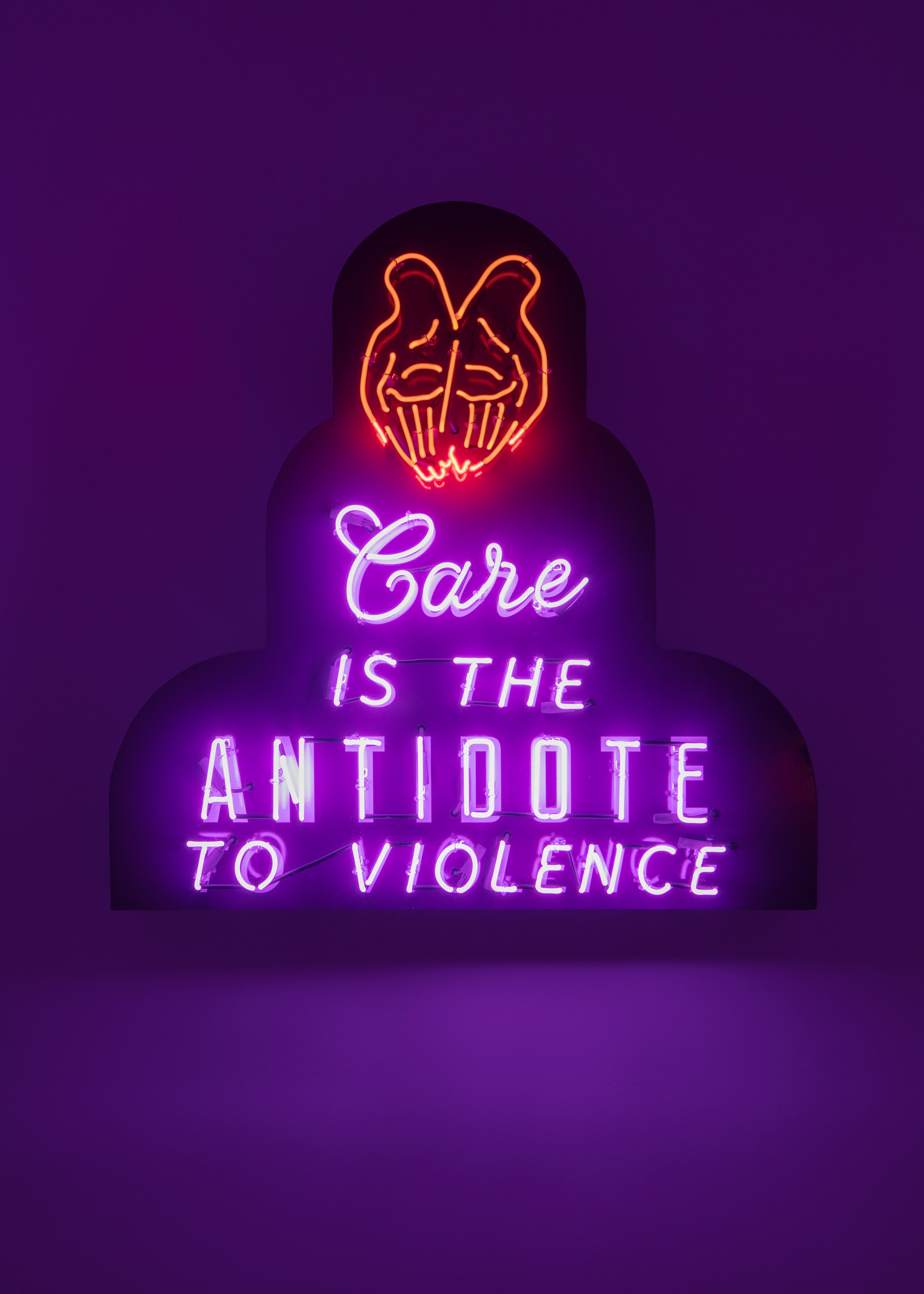

Across from Precious Memories is Citational Ethics (Saidiya Hartman, 2017), a hanging sculptural piece made primarily from neon, a first for Gary. Topped by a neon outline of outstretched palms, the phrase “care is the antidote to violence” glows in vivid purple and gold in the dim light of the gallery space. The following text originates from a 2017 salon at Barnard in celebration of scholar Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake, a 2016 book that discusses Black American collective memory of anti-Black violence and how it reverberates through our archives, actions, and visual cultures. Said by Saidiya Hartman in response to Sharpe’s work, Gary describes these words as “an arrow to the heart,” saying she “[remembers] having a visceral reaction when she heard [Hartman] say it.” Gary sees Hartman’s words as “the underlying thread of the whole show. You could have called this show Care is the Antidote to Violence, you know?…It’s a position I’m taking in relation to the archive and the human beings whose lives were affected in this archive.”

The careful considerations in regards to the wide archive of representation of Black women in media raised by Citational Ethics (Saidiya Hartman, 2017) carry over into The Giverny Suite. In the video, Gary uses the aforementioned audio from Diamond Reynolds’ Facebook Live video. The audio is horrific and jarring on its own, but Gary made a conscious choice to not use the video image because she does not believe that “it’s necessary to show a dead or dying, traumatized Black body in [her] work.” Gary makes clear that she does not see omitting the image of violence as an erasure of Philando Castile’s murder because “the audio does a lot of work here.” Her framing of this potion of archival fits back within the ideas outlined by Christina Sharpe and Saidiya Hartman: “I’m able to centralize Diamond in order to understand her position, while still communicating the brutality of this arbitrary violence which Black people are subject to in this country. It’s a personal aspect of my creative philosophy.”

The care that Gary infuses in every fiber of this show is palpable, and her care ethic is most present in the series of interviews interspersed throughout the video installation of Black women in Harlem. Gary says that these interviews were inspired by Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s 1961 cinéma-vérité film Chronicle of a Summer to “engage with this kind of ethnographic experiment of vox populi— woman on the street, voices from the people.” Similar to Chronicle of a Summer, Gary asks her subjects a simple yet unnervingly open question: “do you feel safe?” This portion of filming required a larger crew, and Gary assembled a crew of “90% women,” including New York-based cinematographer Mia Cioffi-Henry. The interviews became essential to video because of the ways that they explore “ideas around safety, bodily autonomy, the freedom to move around democratic space without feeling threatened or vulnerable—in your body, in the world.” While Gary’s considered artistic ethic has wide applications, it is important to note that flesh needs to be loved is designed to center Black women and their experience living in political and societal structures that are structurally against them. The interviews purposefully include only Black women in their exploration of societal themes, a radical act considering that conceptions of normalcy and security are tied up within societal white supremacy and misogyny that sees the wants, needs, and considerations of Black women as an afterthought.

“When I tell people that I make films for and about Black people, they think, ‘oh maybe this is a small focus,’ but I think that this is a very large focus,” Gary says, “And folks like [writer] Toni Morrison and [artist] Simone Leigh have affirmed this position, of focusing and centering Black womanhood, or Blackness period, and being able to arrive at some sort of broad or ‘universal’ idea.” Gary’s focus is essential to her current artistic practice and is what makes her filmmaking so vital: she gives her interview subjects–who she refers to in our correspondence as “[her] collaborators” the agency and space on-screen that she has as the film’s creator. According to Gary, the women and girls in The Giverny Suite “are hailing from all over the globe, various Caribbean nations, African nations, parts of New York, parts of the American South. It’s also an intergenerational group.” Gary considers this to be “a real example of how varied Black womanhood is,” and the film is made all the more powerful by this radical inclusivity she champions as a filmmaker and her palpable compassion, not only for her subjects but for herself as a Black woman–all exploring their physicality, emotions, and power in the space Gary has lovingly created.

Sitting on the cold floor of Paula Cooper’s 21st Street outpost, I felt and understood Gary’s approach to archival care and her purposeful centering of Black women. It’s the opening of the exhibition, packed with the artists’ friends and strangers there to see the much-hyped show. All of us sit fully engaged with the work, hushed chatter across the room about the work and its explicit call to action. The sense of camaraderie in the room was powerful—not just a sense of solidarity but active, compassionate participation in the growth of ourselves and communities. In Gary’s application of care to archival material, her Black female protagonists, and to her intricate artistic process, she offers new ways forward through radical empathy and filmmaking.