‘It’s like fighting with the classics’: The artist battles ancient demons and tech-fueled disillusionment.

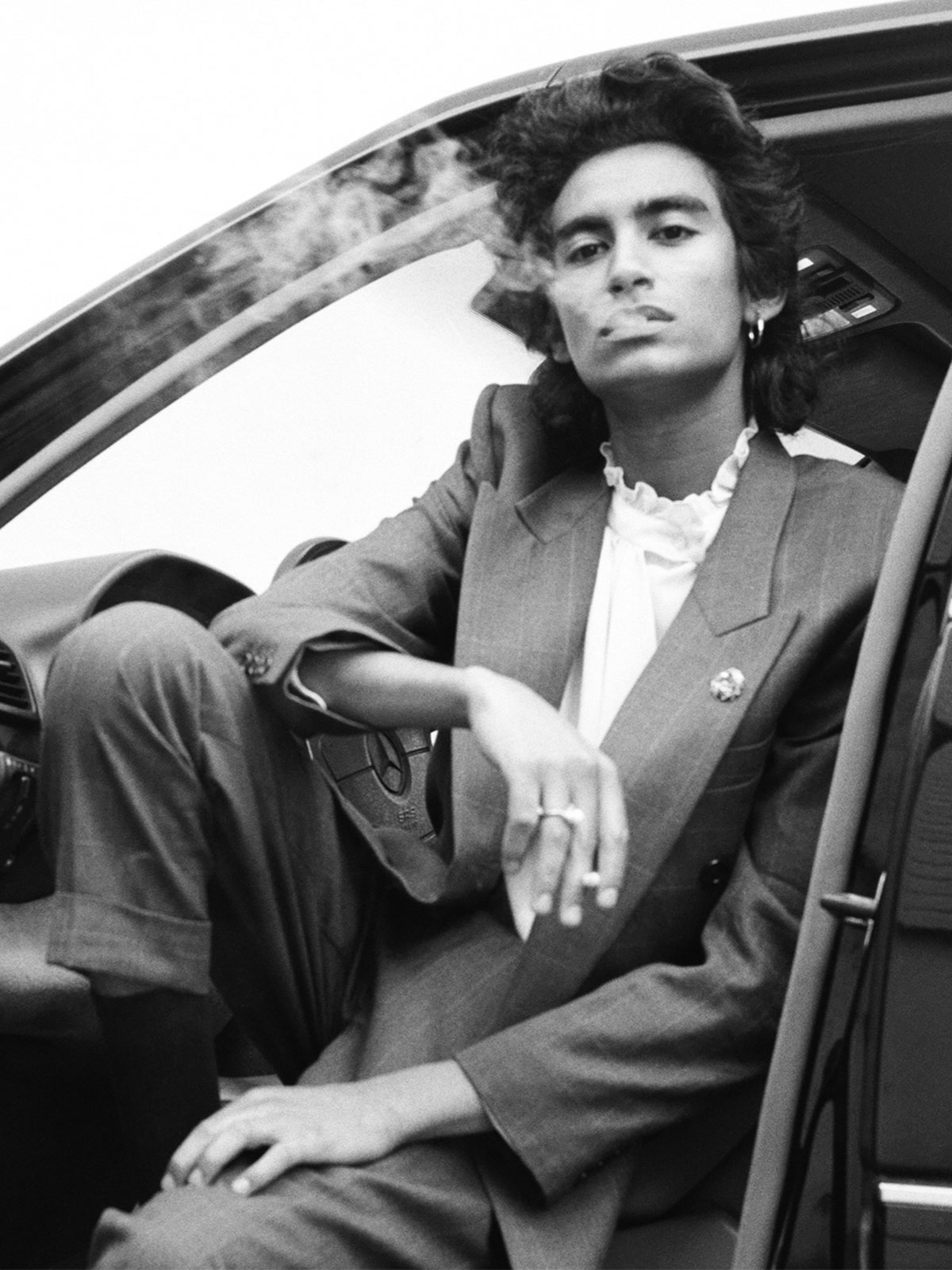

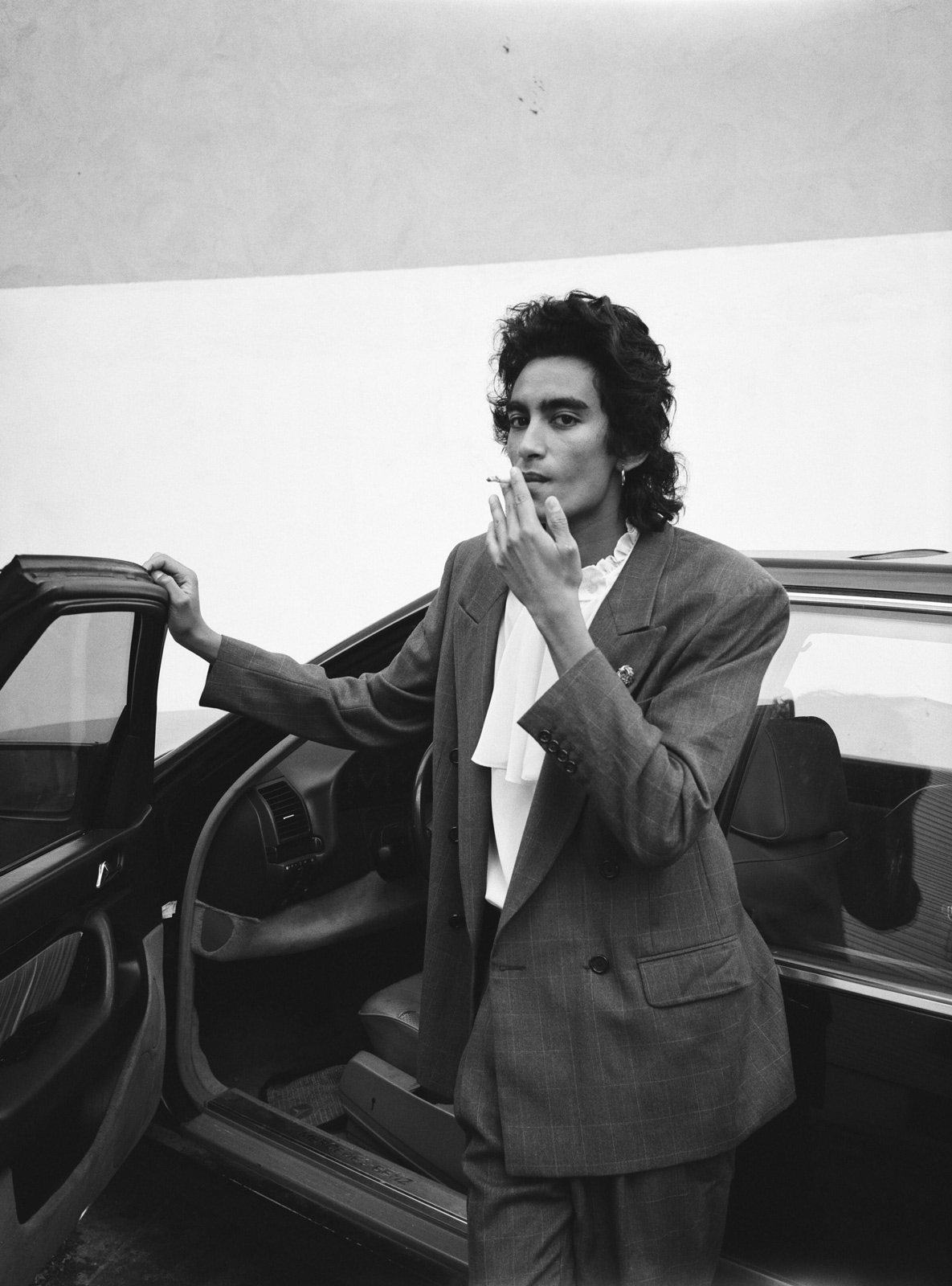

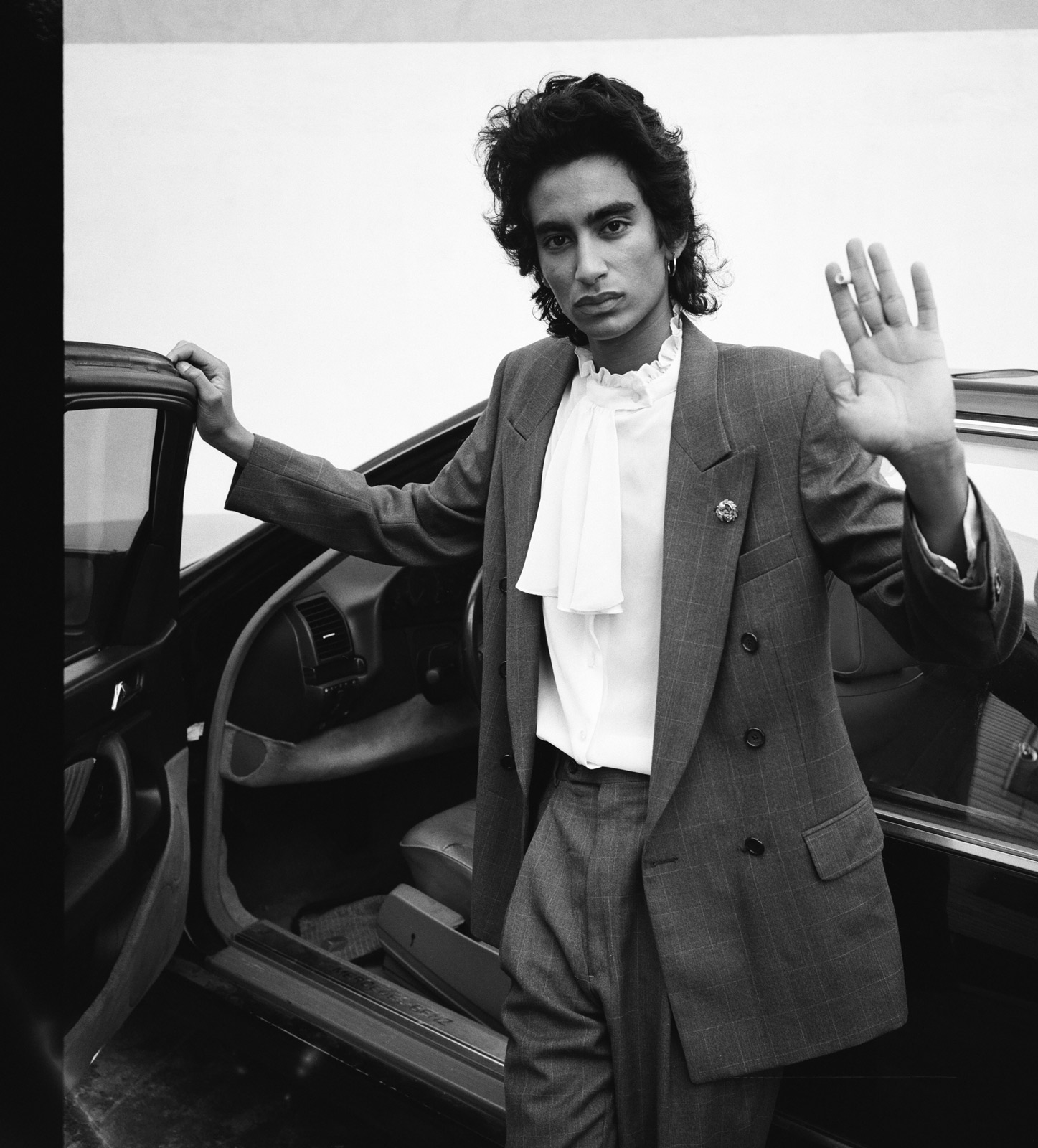

New York-based singer-songwriter Quiet Luke, also known as Alec Bahta, has impressed critics with his ambitiously layered pop music. Since the release of his first EP, Beholden, while still a student in 2016, Quiet Luke has been hard at work on his debut album. 21st Century Blue, released on December 4, is a densely layered concept album that describes the experience of coming of age in a time rife utopian optimism and dystopian anxiety. A graduate of NYU’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music, Luke’s debut album attempts to synthesize traditional elements of pop songwriting with funk, jazz, electronic and experimental noise, ultimately producing an album that joins a deeply human sense of emotion and melodrama, with the encroaching sense of artificiality that seems to characterize our contemporary lives. On tracks like “Familial,” Luke filters his singular sensibilities through electronic frequencies and noise, finding his own unique voice in the spaces between the traditional pop-ballad and the schizophrenic chaos of experimental electronics. Meanwhile, on songs like “Interference” and “Something to Lose,” Luke uses modulating time signatures, unsteady tempos, and glitchy, altered vocals to capture the simultaneous feelings of anxiety and excitement contingent to coming of age in a digitally inter-connected world, a world which seems to offer infinite opportunities for beauty and discovery, even as it is increasingly plagued by “empty glances and false information,” he sings. We caught up with Quiet Luke a few days after his first album dropped to discuss the experience, his writing process, his influences, and the future of music.

Rhodes Murphy: How are you doing?

Quiet Luke: I’m doing pretty well today. It’s been a rollercoaster week but today’s been pretty good.

Rhodes: What’s been going on?

Luke: I had a really, really good listening party, like, just a bunch of beautiful people that I love around me listening to it in person. I had a really emotional experience, I had an ice sculpture bust of my head that people were taking pictures with and stuff. I was trying to use the ice sculpture to give the album an air of hellenism and a sense of romantic iconography. We see this kind of iconography everyday on Instagram, I wanted to actually make myself into an icon with the statue and just let it melt for 36 hours. I was working on the album for a really long time, it’s a complicated mix of emotions when you put something out in the world that you’ve been crafting and imagining coming out for, like, three or four years.

Rhodes: So you were working on 21st Century Blue for four years?

Luke: Not four years consistently, but I remember knowing that I wanted to put out an album that was a work of a longer period of time in late 2015, I think I even had the name. I didn’t expect it to take as long as it did and it’s not like I didn’t work on anything else in between. I released this EP called Your Happy Place in 2017–that was actually just me taking a break from this album. The album was making me go crazy and I found myself not able to revisit some of the emotions and topics I was writing about. So I just made a parallel, it was kind of like, I’ve been working so hard on this album and I just want to have fun and make cool pop songs. I put it out as an EP because I knew the album was going to take a little longer, and here we are two years later.

Rhodes: You mentioned trying to evoke a Hellenistic vibe for the listening party. What kind of role does iconography play in how you think about the album and the project?

Luke: The Hellenistic thing encompasses a lot for me. It’s me trying to understand humanity in this time of ‘data,’ where it’s almost like we’re becoming transhuman; verging on becoming cyborgs. [The ancient iconography] just helps me understand—I wanted to explore emotions and things that I hadn’t gotten over from my childhood and early adolescence. It’s kind of abstract; the album’s not really about human form, but it’s about human emotion. With the way the songs were produced I see this architectural attention to form that’s being warped as you go through it. I see music in almost pure form, in a way. Unlike a building, it could change at any moment and take a new shape just by just shifting sounds and stuff like that.

I almost see the album as a Greek drama. I was definitely looking at Greek drama and Shakespeare, narratively—which is also why the album took so long. I was writing songs and I knew what I wanted the arc of the album to be, but I was learning so much and changing so much that it just took a while. I’m kind of off on a huge tangent now.

Rhodes: No! Are there specific references to literature or film that specifically influenced you?

Luke: Hamlet. Blade Runner 2049 was very influential, and the original one for me too, but more so 2049. A lot of people really hated that movie. I get it, the plot kind of sucks. But the production design and the art direction was just so beautiful, it made me emotional. There’s something about the scene where—have you seen the movie yet?

Rhodes: No, I actually haven’t seen it yet. I’m a fan of the original though.

Luke: Well, I guess I won’t talk about it because I don’t want to spoil it for you.

Rhodes: No, you can do it.

Luke: Are you not a big sci-fi person?

Rhodes: No, I am—I just don’t care about spoilers.

Luke: Okay. There’s this scene in the last third of the movie where Ryan Gosling has to confront Harrison Ford, who’s hiding out in Las Vegas in this abandoned casino-type building. It kind of draws these parallels between gambling and religion because Ryan Gosling is, like, creeping around this version of Las Vegas that looks like a bunch of abandoned religious temples. Eventually he ends up in this lounge or theater area where there’s projections of Elvis playing. Nobody is singing but Elvis is playing. I forget what Ryan Gosling and Harrison Ford are fighting over but they start fighting with this projection of Elvis playing in the background.

I don’t know what it was but there is something about that scene that struck a chord with me. It’s kind of like us fighting with the classics. It’s almost like an Oedipal thing; culturally, we still haven’t moved on from a time where nothing has been as famous than Elvis or The Beatles, and people still hold these idols and ideals about how things should be. I don’t think that is going to go away any time soon, but at the same time I’m hopeful for new inclusive spaces for people in culture. I didn’t really expect us to be talking about this, I hope you can turn this into something that people can read.

Rhodes: I mean, I’m having fun.

Luke: Okay.

Rhodes: So, I was thinking about Picasso’s Blue Period while listening to the album, and thinking about the sense of cultural loss and melancholy he was evoking at that time. Is 21st Century Blue working in a similar way for you?

Luke: I think it might be more complicated than that. It’s a loss but I think it’s more responding to change and disillusionment with the sheer state of the world. I think it’s a hard time for people in their early 20s, coming to understand that people who have authority, ‘adults,’ don’t really know what they’re doing and that they’re leaving a lot of issues that the younger generation is going to deal with. So in a way it’s kind of like the classic ‘music is therapy’ thing, where this album was how I made sense of those feelings. I would spill my guts in these sessions and then try to make sense of it after and make it something that is palatable in a pop context.

Rhodes: You’ve talked before about how you see contemporary culture as kind of stuck in this postmodern aesthetic. I was wondering how you were responding to that with this album.

Luke: Well, I guess what I’ll say is that it’s something that I realized later on. I responded to it by making what I saw as the most timeless and most quote-unquote ‘classic’ thing I could. That’s probably my next step; figuring out how I escape the textbook standard of what a ‘good’ musician is, and how I survive while doing that. [With this record] I felt like I had to make something that was tried and true. I had to make an album that was both uncompromisingly experimental and had a pop sensibility that would exist in a very specific space. I wanted this album to serve as a foundation for what I do in the future. I don’t think I escaped postmodernism on this album. But it was intentional.